This is Chapter One of seven, about a family line which begins in Europe and through the remarkable deeds of two twin brothers, they found an expansive family line in America.

Clara (McClintock) DeVoe is our Great-Grandmother on our mother Marguerite (Gore) Bond’s maternal side of the family. Through her family, she is our direct connection to Scotland during the period of colonial immigration. On our father Dean Bond’s side of things, some of our Irish relatives went to Scotland to find work (and survive) during the Great Hunger of the potato famine. They also had many children there, but maintained their cultural identity as Irish people. (His side then immigrated to the United States in the 1880s).

Clara McClintock’s family also immigrated, but at a much earlier time than the Irish side did. Their story starts here…

Fàilte! (This Means Welcome in Scottish Gaelic)

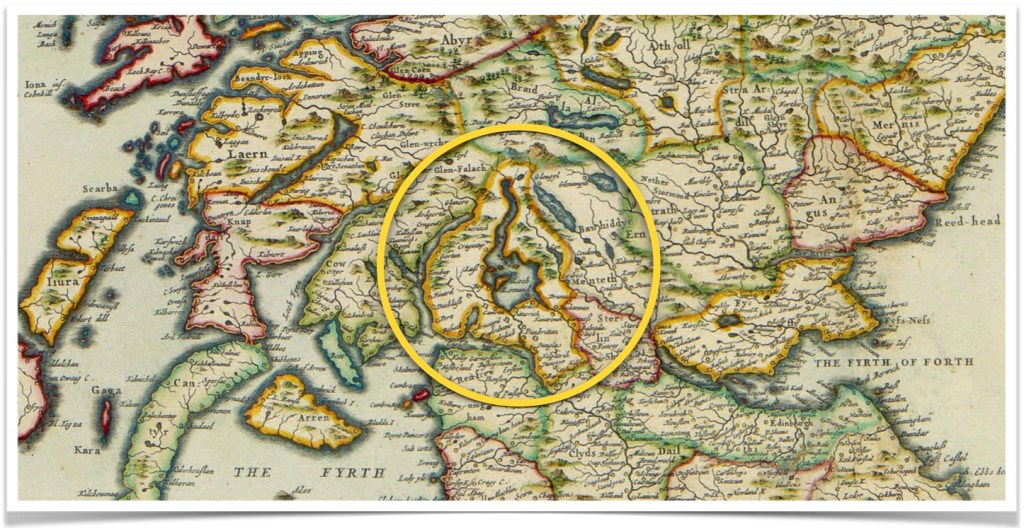

Our story begins in the Highlands of Scotland, around the shores of the famous Loch Lomond. Our ancestors in this family line are descended from the Clan McClintock families who lived there. The Loch is pictured in this map almost exactly in the center section.

But first, let’s explain the origins of the surname, and then its affiliation as a Sept of the Clan Colquhoun from this area. (1)

All Around Loch Lomond…

The following text is excerpted from The History of the McClintock Family, by Col. R. S. McClintock. “The name Mac Lintock, McLintock or McClintock is a Highland one, and, in Scotland, though nowhere else, is chiefly to be found in the South-western Highlands and especially in the district round Loch Lomond, formerly subject to the Laird of Luss whose name was Colquhoun.

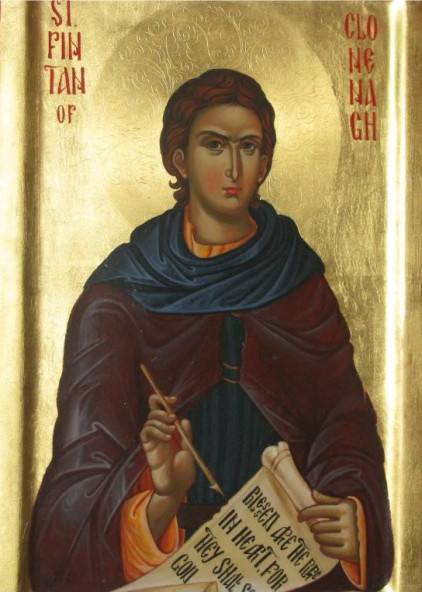

In Gaelic it is spelt ‘Mac Ghiolla Fhionntog’, or – to adopt the Scottish method which omits the mute letters – ‘Mac’ill’intog’, and means ‘son of the servant (i.e. religious follower) of Fintag’. Fintag, like the better known name of Fintán, is a diminutive of Fionn (anglicized Finn) meaning fair-haired”.

(Image courtesy of Ana St. Paula).

[R. S. McClintock was] “…making researches in Edinburgh [and discovered]…the record of an action taken in 1528 by the Abbot of Cambuskenneth against the parishioners of the parish of Kilmarnock in Dumbartonshire. These parishioners were sued for refusing to pay their ‘tiends’ or tithes which were due to the Abbot, who was patron of the parish… probably caused by the Abbot neglecting to appoint a minister and [instead] putting the stipend into his own pocket.

However this may be, we have a list of the defaulting parishioners with the amounts of their assessments, and among such names, in modern spelling… we find three McClintocks: Andrew of Ballagane, Donald of Balloch and Andrew of Boturich: probably there was only one Andrew – who was assessed on two separate holdings. Balloch is at the south end of Loch Lomond where the river Leven flows out of the Loch and Ballagane and Boturich lay 2 and 4 miles respectively to the northwards.”

“I had always imagined that the McClintocks were people of importance and I pictured them as striding over the heather in kilts with an eagle’s feather in their bonnet, but this dream was rudely shattered when I was lunching with the Duke of Argyll at Rosneath — I asked whether there were many of the name in Argyll. ‘Oh yes,’ said the Duke, ‘there are plenty – they are mostly tinkers, water tinkers.’* Water tinkers, I may mention, is a branch of the trade much looked down upon by the other tinkers. However, the Duke added ‘They’re very good chaps: you’d like them’.”

From our research, we have learned that Water Tinkers were likely tinsmiths who traveled by boat. (2)

Clan Colquhoun

“Clan Colquhoun (Scottish Gaelic: Clann a’ Chombaich) is a Highland Scottish clan whose lands are located around the borders of the Loch Lomond lake. The Clan Colquhoun International Society, the official organization representing the clan considers the following names as septs* of clan Colquhoun. However several of the names are claimed by other clans, including Clan Gregor – traditional enemy of clan Colquhoun.

As follows — Calhoun, Cahoon, Cahoone, Cohoon, Colhoun, Cowan, Cowen, Cowing, Ingram (or Ingraham), Kilpatrick, King, Kirkpatrick, Laing (or Lang), McCowan, McMains (or McMain), McManus, McClintock and McOwan, Covian, McCovian.”

*In the context of Scottish clans, septs are families that followed another family’s chief, or part of the extended family and that hold a different surname. These smaller septs would then be part of the chief’s larger clan. A sept might follow another chief if two families were linked through marriage, or, if a family lived on the land of a powerful laird [estate owner], they would follow him whether they were related or not.

The clan chief’s early stronghold was at Dunglass Castle, which is perched on a rocky promontory by the River Clyde. Dunglass Castle was also close to the royal Dumbarton Castle, of which later Colquhoun chiefs were appointed governors and keepers.” (Wikipedia)

“The Colquhouns can claim to be both a Highland and Lowland clan, as their ancient territory bestrides the Highland Boundary Fault, where it passes through Loch Lomond”. (The National). (3)

We Know Where They Lived — But, How Did They Live?

We are of course curious about the lives of these relatives, but we know little about them until they immigrate to British North America. They did come out of the Scottish culture of the late 17th century, so what was that like?

“The Highlands, for most people, started at Loch Lomond and The Trossachs. They still do – but no longer in the sense understood by Lowland Scots until well into the 18th century.

The Highlands were a different society, where the Highland clan system held different values. The feudal system of Lowland Scotland (and England), where ‘vassals’ held land from ‘superiors’, did not prevail in the Highlands. Instead land tenure was closely linked to kinship and loyalty – members of the clan had an allegiance to their chief, a kind of mutual protection whereby the clansfolk lived securely in their territories but would unswervingly answer the chief’s call to arms if it came. In effect, clans were – potentially – private armies. In mediaeval Scotland they had even threatened the established monarchy.

(Image courtesy of 1st Dibs).

A clan’s wealth was formerly measured in cattle (as a means of seeing them through the harsh Highland winters). Many of the clans around Loch Lomond and The Trossachs, closest to the Highland line, and with the rich farms of the Lowlands within easy reach, gained a reputation as cattle-thieves. At the very least they had expertise both in cattle-droving or protecting cattle from other marauding clans.” (Clans of Loch Lomond & The Trossachs)

There Were Established Levels to Everything

“Scotland in this period was a hierarchical society, with a complex series of ranks and orders” for those that lived in the urban centers and the rural areas:

Of course, at the top we can see the Monarchy, and just below them are the High Noble Classes, consisting of the Dukes and Earls.

In rural society, we see some middle ranking people, mostly defined by how much land they owned. At the Rural Top were the Lairds / Bonnet Lairds, who owned the most; the Yeoman, (still major landholders); the Husbandmen (smaller landholders); the Cottars (peasant farmers). In urban society, at the upper end we see the Burgesses, and the Alderman Bailies, who were essentially different levels of municipal administrators. Then the merchant class, craftsmen, workers, and brute laborers. (Wikipedia)

Observation: This societal hierarchy was probably very hard to transcend. In records that have survived to this day, we see that our later McClintock ancestors could sign their names, and read and write. We know this through their participation in local government. But some other accounts also describe them in a bit rougher terms regarding their behaviors. In regard to Scotland, we are not sure about what social rank they were inhabiting, but they were from Glasgow, so it was likely the Merchant Class, or Craftsmen. They had to have the resources necessary to pay for their ship passage to the Colonies, and to then provide for themselves afterwards.

published in the Theatrum Scotiae, 1693.

(Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons).

“17th century Scotland looked very different to today: it was predominantly rural, the landscape being made up of clusters of small farms, surrounded by narrow strips of cultivated ground (rigs) in an otherwise barren landscape. There were few trees or hedges, but plenty of bogs, mountains and moorland. There were very few roads, with access generally being by muddy tracks that were frequently impassable due to the weather. Most of the farms were quite small — usually less than 300 acres in total. Individual families lived on as little as 20 acres and survived by subsistence farming.

The departure of King James to London in 1603 [as Heir to the English throne after Elizabeth I’s death] brought about change, particularly for wealthy Scottish landowners. If they wanted to remain part of the King’s court and retain their political influence, then they had to follow James to England. As a result, many became ‘absentee’ landlords. In England, however, they became aware of potential improvements and alternative methods of farming that would fuel the agricultural revolution that followed in the 18th century.” (Scottish Archives for Schools, a division of the National Records of Scotland)

The actions of these absentee Scottish landlords precipitated a big change in Scotland called the Lowland Clearances. From Wikipedia, “As farmland became more commercialized in Scotland during the 18th century, land was often rented through auctions. This led to an inflation of rents that priced many tenants out of the market. Thousands of cottars and tenant farmers from the southern counties (Lowlands) of Scotland migrated from farms and small holdings they had occupied to the new industrial centers of Glasgow, Edinburgh and northern England or abroad.” Big population changes were starting to occur. (4)

Lanarkshire and the City of Glasgow

Our ancestors had begun in the areas around Loch Lomond, but had migrated south down the River Clyde, to the area of the City of Glasgow in Lanarkshire. From Wikipedia, “By the 16th century, the city’s tradesmen and craftsmen had begun to wield significant influence, particularly the Incorporation of Tailors, which in 1604 was the largest guild in Glasgow; members of merchant and craft guilds accounted for about 10% of the population by the 17th century. With the discovery of the Americas and the trade routes it opened up, Glasgow was ideally placed to become an important trading centre with the River Clyde providing access to the city and the rest of Scotland for merchant shipping...

Access to the Atlantic Ocean allowed the import of slave-produced cash crops such as American tobacco and cotton along with Caribbean sugar into Glasgow, which were then further exported throughout Europe. These imports flourished after 1707, when union with England made the trade legal.” Interestingly in 1726, the famous English novelist Daniel Defoe (of Robinson Crusoe) describes Glasgow as “The cleanest and best-built city in Britain; 50 ships a year sail to America”.

It is from this location that two brothers decided to immigrate directly from Glasgow to the British Colonies in North America. This city underwent much change in the century after they left, losing much of its rural character. (5)

Who Immigrated to North America in the 17th Century?

“Immigration to North America in the 17th and 18th centuries reflects a complex blend of motivations. European royals, political, and business leaders sought wealth, power, and resources. Missionaries wanted to convert Native Americans to Christianity, while others looked to escape religious persecution. Violent conflicts, high land rents, and criminal punishments also caused—or forced—people to sail to the colonies.

The first immigrants came mainly from northern European countries. They arrived to establish a new life in North America—the British colonies, New France, New Netherlands, New Sweden, or New Spain. In the 18th century, European migration to North America continued and increased, as colonies became more established.

English, Welsh, Irish, Scottish, and Scots-Irish people from Ulster [Ireland]left their homelands for myriad reasons. Religious refuge was sought by Quakers, Puritans, Presbyterians, Congregationalists, and Catholics, for example. And as the British agricultural system shifted in favor of larger landholders—through the 18th-century Enclosure Movement—smaller farmers were forced off their lands. This prompted many to journey across the Atlantic.” (Ancestry) (6)

Who are the — Scots / Scotch-Irish / Scots-Irish / Ulster-Irish / Ulster-Scots ?

We have been observing how some writers use different terms when describing these ancestral groups who came to British North America. (It’s confusing enough to drive one to drink!) Our ancestors appear to have come directly from Scotland to New England, without stopping over in England, or Ireland (now chiefly known as Ulster-Scots). Therefore, we agree with this expression — “Scotch is the drink, Scots are the people.”

Writer Michael Montgomery helped us understand these various descriptors when he wrote, “I began noticing Scots-Irish [no small h]. I observed that academics and genealogists used it to some extent… to conform to usage in the British Isles, where today people from Scotland are called Scots rather than Scotch.

In the United States Scotch-Irish [notice the small h] has been used for Ulster immigrants (mainly of Presbyterian heritage) for more than three centuries and well over one hundred years for their descendants. Why Scotch-Irish rather than Scots-Irish? Simply because, as we will see, people of Scottish background were known as Scotch in the eighteenth century, so that term was brought to America, where it took root and flourished.

In the nineteenth century Scotch-Irish widened to encompass other Protestants (Anglicans, Quakers, etc.) and eventually some writers applied it to Ulster immigrants collectively [Ulster-Scots] because they were presumed all to have absorbed the Scottish-influenced culture of Presbyterians who had come to Ulster from Scotland in the seventeenth century”. (7)

Therefore, it seems that these ancestors are, to put it simply, Scots.

We don’t definitively know why the McClintocks came to British North America, but we do understand that they were likely Presbyterians based upon their histories. In the next chapter, we will lift a glass and toast to them as they eventually make plans to journey across the Atlantic Ocean to their new home.

Following are the footnotes for the Primary Source Materials,

Notes, and Observations

Fàilte! (This Means Welcome in Scottish Gaelic)

(1) — one record

Click on this link below to watch this very short video:

How to Pronounce Fáilte? (WELCOME!) | Irish, Gaelic Scottish, Pronunciation Guide

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ijgg-z1nPqs#:~:text=Information%20%26%20Source%3A%20Fáilte%20(Irish,a%20word%20meaning%20%22welcome%22.

All Around Loch Lomond

(2) — five records

Saint of the Day – 17 February Saint of the Day – 17 February – Saint Fintan of Clonenagh (c 524 – 603)

Saint Fintan of Clonenagh (c 524 – 603)

The “Father of the Irish Monks”

https://anastpaul.com/2021/02/17/saint-of-the-day-17-february-saint-fintan-of-clonenagh-c-524-603-father-of-the-irish-monks/

Note: For the data.

Anastpaul.com

By Artist unknown

https://anastpaul.com/2021/02/17/saint-of-the-day-17-february-saint-fintan-of-clonenagh-c-524-603-father-of-the-irish-monks/

Note: For his portrait.

Fintán of Taghmon

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fintán_of_Taghmon

Note: For the data.

“In Scotland, he is venerated as the patron saint of Clan Campbell.”

Scotland in the Early Middle Ages (map)

Attributed to Robert Gordon of Straloch, circa 1654

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Atlas_Van_der_Hagen-KW1049B11_038-SCOTIA_REGNUM_cum_insulis_adjacentibus.jpeg

Note: For the map and data. “In 1654 Joan Blaeu (1598-1673) published an atlas which was completely dedicated to the kingdom of Scotland. Blaeu composed this atlas in cooperation with the Scottish Government. The framework of the atlas was a collection of manuscript maps by the Scottish pastor Timothy Pont (c. 1560- c. 1614). This material had been prepared for publication from 1626 under orders from Blaeu by the Scottish cartographer Robert Gordon of Straloch (1580-1661) who completed the collection with 11 new maps. This general map of Scotland is one of those new maps. Along the right side of the map is an inset with representations of the islands north of Scotland.”

A History of The McClintock Family

By Col. R. S. McClintock

https://www.ancestry.com/sharing/12464119?h=4f58fa

Note: For the text.

Clan Colquhoun

(3) — seven records

Clan Colquhoun

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clan_Colquhoun

and

Sept

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sept

Note: For the data.

Colquhoun Gallery Images:

Colquhoun Tartan Shop

https://www.pinterest.co.uk/pin/382383824601666368/

Note: For the portrait of the 28th Clan Chief — Colonel Sir Alan Colquhoun of Luss (1838–1910).

and

Chiefs of Colquhoun and their country, Volume 2

https://digital.nls.uk/histories-of-scottish-families/archive/96522650#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0&xywh=-1363,-196,5224,3907

Note: For Arms and Book Frontispiece.

and

Scot Clans

Clan Colquhoun History

http://109.74.200.198/scottish-clans/clan-colquhoun/

Note: Excerpt from Gill Humphreys Clan Map of Scotland.

File:Dunglass Castle.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dunglass_Castle.jpg

Note: For the image. From Wikimedia Commons — “Ruines du Chateau de Dunglass, Dunglass Castle” drawn by F.A.Pernot and printed by A.Dewasme. Published in Vues Pittoresque De L’Ecosse,1827. This cannot be Dunglass Castle, East Lothian, because that building was some distance inland, next to a stream, whereas this image is clearly next to a substantial body of water, i.e. The Clyde”.

The Best Tales from Scotland’s Most Prolific Lowland Clans

by Hamish MacPherson

https://www.thenational.scot/culture/20061267.best-tales-scotlands-prolific-lowland-clans/

Note: For the text.

We Know Where They Lived — But, How Did They Live?

(4) — seven records

Friends of Loch Lomond & The Trossachs Park Clans

Clans of Loch Lomond & The Trossachs https://www.lochlomondtrossachs.org.uk/park-clans

Note: For the text.

Antique Scottish Landscape Highland Cattle on Loch Pathway Mountains

by A. Lewis

https://www.1stdibs.com/art/paintings/landscape-paintings/lewis-antique-scottish-landscape-highland-cattle-on-loch-pathway-mountains/id-a_12176282/

Note: For the landscape painting.

Scottish Society in the Early Modern Era

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scottish_society_in_the_early_modern_era

Note: For the data, A table of ranks in early modern Scottish society.

A Scottish Lowland farm from John Slezer’s

Prospect of Dunfermline

published in the Theatrum Scotiae, 1693

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agriculture_in_Scotland_in_the_early_modern_era#/media/File:17thC_Scottish_Lowland_farm.jpg

Note: For the image.

The Scottish Archives for Schools

Seventeenth Century Scotland

https://www.scottisharchivesforschools.org/unionCrowns/17thCenturyScotland.asp

Note: For the text.

Prospect of Dunfermline

by John Slezer, circa 1693

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:17thC_Scottish_Lowland_farm.jpg

Note: For the illustration.

General History of the Highlands

The Living Conditions in the Highlands prior to 1745 (Part 1)

https://www.electricscotland.com/history/working/index.htm

Note: For the plough image.

Lowland Clearances

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lowland_Clearances

Note: For the data.

Lanarkshire and the City of Glasgow

(5) —three records

History of Glasgow

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Glasgow

Note: For the text.

Random Scottish History

Port Glasgow from the South East, circa 1700.

Drawn by J. Fleming, engraved by Joseph Swan.

https://randomscottishhistory.com/2018/05/23/port-glasgow-pp-87-98/

> Random Scottish History, Port Glasgow, pp.87-98

Note: For the landscape image.

Timeline of Glasgow History

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_Glasgow_history

Note: For the data.

Who Immigrated to North America in the 17th Century?

(6) — one record

Immigration in the 1600s and 1700s

https://www.ancestry.com/c/family-history-learning-hub/1600s-1700s-immigration

Note: For the text and data.

Who are the — Scots / Scotch-Irish / Scots-Irish / Ulster-Irish ?

(7) — two records

The Ulster-Scots Language Society

Scotch-Irish or Scots-Irish: What’s in a Name?

By Michael Montgomery

http://www.ulsterscotslanguage.com/en/texts/scotch-irish/scotch-irish-or-scots-irish/

Note: For the text.

Scotch Whisky – A Primer From Vintage Direct

https://www.nicks.com.au/info/a-scotch-whisky-primer-761065

Note: For the vintage whisky advertisement images.