This is Chapter Two of seven. Here we are examining some of the colonization that Europe attempted in the decades before the Pilgrims sailed to British North America.

Preface — Show Me The Money

The first wave of European colonization began with the initial Spanish and Portuguese conquests and explorations. Those kingdoms were the primary ones involved with the European colonization of the New World — thus, the Spanish and Portuguese became profoundly rich. “It was not long before the exclusivity of Iberian claims [Spain and Portugal] to the Americas, was challenged by other European powers, primarily the Netherlands, France, and England.

[Everyone wanted access to the (potential) resources available to them.] “…the English, French and Dutch were no more averse to making a profit than the Spanish and Portuguese, and whilst their areas of settlement in the Americas proved to be devoid of the precious metals found by the Spanish, trade in other commodities and products that could be sold at massive profit in Europe provided another reason for crossing the Atlantic — in particular, furs from Canada, tobacco and cotton grown in Virginia, and sugar in the islands of the Caribbean and Brazil.” (Wikipedia) (1)

England Finally Gets In The Game

“In the early 1600s it was finally England’s turn to play the game. Much like the young Spanish conquistadores coming to America a century earlier, young English aristocratics, or for that matter anyone seeking social betterment, looked to America in the hope of finding American gold with which they could buy land and thus social status.” (Colonial Foundations)

with arms of Sir Walter Raleigh, English vessels, dolphins, fish, whales and sea-monsters,

by John White, circa 1585-1593. (Image courtesy of The British Museum).

Virginia Was the Mother of the Colonies —

“The Spanish had established Saint Augustine, Florida in 1565 as a strategic outpost to protect Spain’s Caribbean empire from English privateers. Between Newfoundland and Spanish Florida was a vast unsettled territory. Raleigh named this area Virginia an honor to Queen Elizabeth, (the Virgin Queen), with whom he sought favors. For many years thereafter the vast temperate region of North America was referred to as Virginia. It had no boundaries, and no government.

Each of the other original colonies was directly or indirectly carved out of Virginia. It was the first territory to be claimed by England in North America. At its maximum extent, Virginia encompassed most of what is now the United States, as well as portions of Canada and Mexico.

Virginia was the first of the thirteen original states to be founded and settled. It was generally the tradition of the English during the colonial period to establish large geographic units, and then to subsequently sub-divide them into smaller more manageable units. This two-phase process was conducted in order to establish legal claims to maximum territory.” (See footnotes, How Virginia Got Its Borders — HVGIB) (2)

Wearing the Jewel Called the Three Brothers in His Hat, circa 1605, (after) John de Critz .

King James I and the Virginia Company of 1606

Queen Elizabeth I died in 1603, and the continued development of colonies in the Americas then fell to her successor. “It would have to wait for a new monarch before colonization would become a reality. That monarch was King James I, Elizabeth’s successor. In 1606, he chartered two joint stock companies for the purpose of establishing colonies in Virginia.” (See footnotes, HVGIB)

In Renaissance England, wealthy merchants were eager to find investment opportunities, so they established several companies to trade in various parts of the world. Each company was made up of investors, known as merchant adventurers, who purchased shares of company stock. Profits were shared among the investors according to the amount of stock that each owned. More than 6,300 Englishmen invested in joint-stock companies between 1585 and 1630, trading in Russia, Turkey, Africa, the East Indies, the Mediterranean, and North America.

The Virginia Company emerged at a time when European empires chartered corporations for their imperial efforts. The English East India Company and Dutch East India Company had both recently received royal charters by their governments. (See also The DeVoe Line, A Narrative — One, Holland & Huguenots). The Virginia Company represented a new strategy that relied less on protected trade and ports — this strategy was settler colonialism.

Therefore, the English King James I needed money to continue England’s struggle against Spain and was very willing to charter two new colonization efforts to the New World, for the area (at that point) known overall as Virginia. For this effort he created The Virginia Company on April 10, 1606. It was an English trading company chartered with the objective of colonizing the eastern coast of America. “The [initial] Charter of 1606[which] did not mention a Virginia Company or a Plymouth Company; these names were applied somewhat later to the overall enterprise.” (Wikipedia) Hence, the Virginia Company eventually became two companies:

The Virginia Company of Plymouth was funded by wealthy investors from Plymouth, Bristol, and Exeter such as Sir John Popham. It was responsible for the northern part of Virginia (roughly what was to become New England). On August 13, 1607, the Plymouth Company established the Popham Colony along the Kennebec River in Maine. However, it was abandoned after about a year and the Plymouth Company became inactive. A successor company eventually established a permanent settlement in 1620 when the Pilgrims arrived in Plymouth, Massachusetts, aboard the Mayflower.

The Virginia Company of London was responsible for the southern colony. It was primarily focused on the Chesapeake Bay area of today’s Northern Virginia and Southern Maryland. The company established the Jamestown Settlement in present-day Jamestown, Virginia in 1607. (Overall several sources utilized, see footnotes).

It is quite an understatement to say that establishing a new colony in The Americas took much in terms of resources, and quite honestly, a lot of luck too. Each country was literally building an entire new system for their explorations, along with an ambitious, concurrent new economic model. Hence, the results, whether they understood this or not, were quite new societies.

In summary, Spain, Portugal, and France moved quickly to establish a presence in the New World, while other European countries moved more slowly. The English did not attempt to found colonies until many decades after the explorations of John Cabot, and early efforts were failures — most notably the Roanoke Colony, which vanished about 1590. (3)

Right image: The House of Tudor, Queen Elizabeth I (reigned 1558 – 1603).

The Roanoke Colony, 1587 — ?

We learned from How Virginia Got Its Boundaries, that back “when Sir Walter Raleigh founded the first English settlement on Roanoke Island, there was no Virginia. There was only America… [and that] the failure of Roanoke Island was a financial disaster for Queen Elizabeth. She refused to invest further in colonial enterprises. Virginia remained in name only.” (See footnotes, HVGIB)

Some background —

From Wikipedia, Raleigh “was an English statesman, soldier, writer, and explorer. One of the most notable figures of the Elizabethan era, he played a leading part in English colonization of North America. He helped defend England against the Spanish Armada. He rose rapidly in the favour of Queen Elizabeth I and was knighted in 1585. He was granted a royal patent to explore Virginia, paving the way for future English settlements. In 1591, he secretly married Elizabeth Throckmorton, one of the Queen’s ladies-in-waiting, without the Queen’s permission, for which he and his wife were sent to the Tower of London. After his release, they retired to his estate at Sherborne, Dorset.”

Observation: In addition to the cost of her war with Spain, Raleigh’s subterfuge of a marriage was another reason that Queen Elizabeth I decided not to further invest in his colonial adventures.

A Popular History of the United States, by William Cullen Bryant.

England’s desire for empire building finally started emerging — “Roanoke Colony was founded by the governor Ralph Lane in 1585 on Roanoke Island in present-day Dare County, North Carolina. Lane’s colony was troubled by a lack of supplies and poor relations with some of the local Native American tribes. A resupply mission by Sir Richard Grenville was delayed, so Lane abandoned the colony and returned to England with Sir Francis Drake in 1586. Grenville arrived two weeks later and also returned home, leaving behind a small detachment to protect Raleigh’s claim.

A second expedition led by John White landed on the island in 1587 and set up another settlement. Sir Walter Raleigh had sent him to establish the ‘Cittie of Raleigh’ in Chesapeake Bay. That attempt became known as the Lost Colony due to the unexplained disappearance of its population.”

From left to right: An Indian girl shows off an English doll, Equipment for curing fish used by the North Carolina Algonquins, Ritual dances, and the Village of the Secoton. (Images courtesy of The Trustees of The British Museum, and National Geographic).

“The ship was unable to return right away however, because the English at this point were deeply engaged in this struggle for their very survival against the mighty Spanish Armada. Not until [after] the English survived this danger, three years after originally depositing the settlers in America, was a ship able to send supplies back to the colony. But upon the ship’s arrival, the settlers were nowhere to be seen — nor was there any indication of where they might be or what had happened to them. The cryptic word ‘CROATOAN’ was found carved into the palisade, which White interpreted to mean that the colonists had relocated to Croatoan Island. Before he could follow this lead, rough seas and a lost anchor forced the mission to return to England.”

The news of the Lost Colony put a serious chill on any further thoughts about another such venture — until another generation came along at a time when the lure of gold seemed to be greater than the fear of failure.” (Overall several sources are utilized, see footnotes). (4)

The Roanoke Colony in the Popular Imagination

In today’s world, it seems that almost everyone has heard something along the way about the legend of Roanoke Island. One might think that this is a somewhat new phenomena due to the current omni-presence of social media and clickbait alternative reality programming. However, interest in this mystery goes back much further — nearly 200 years .

“United States historians largely overlooked or minimized the importance of the Roanoke settlements until 1834, when George Bancroft lionized the 1587 colonists in ‘A History of the United States’. Bancroft emphasized the nobility of Walter Raleigh, …the courage of the colonists, and the uncanny tragedy of their loss. He was the first since John White to write about Virginia Dare, calling attention to her status as the first English child born on what would become US soil, and the pioneering spirit exhibited by her name. The account captivated the American public.” (Wikipedia)

originally published in 1841.

There were investigations, but those were done in the very early days of the English presence in North America. Nothing conclusive was then determined about the fate of the colonists. Intriguingly, “Two decades later the English established their first permanent beachhead in the Americas, a hundred miles to the north on the James River, in what is now Virginia. Captain John Smith, the leader of the Jamestown colony, heard from the Indians that men wearing European clothes were living on the Carolina mainland west of Roanoke and Croatoan Islands.” (National Geographic)

Modern scholarship combined with many archeological excavations have all but concluded that the Roanoke Colonists were in the area, but had chosen to integrate into the local tribal cultures to survive.

“They say that the colony vanished and they left behind this cryptic message on a tree, ‘Croatoan,’ and no one knows what it means…

Scott Dawson, President, Croatoan Archaeologist Society,

The reason they do this is mystery sells, right?

But Croatoan is Hatteras Island. It’s clearly labeled on the maps.”

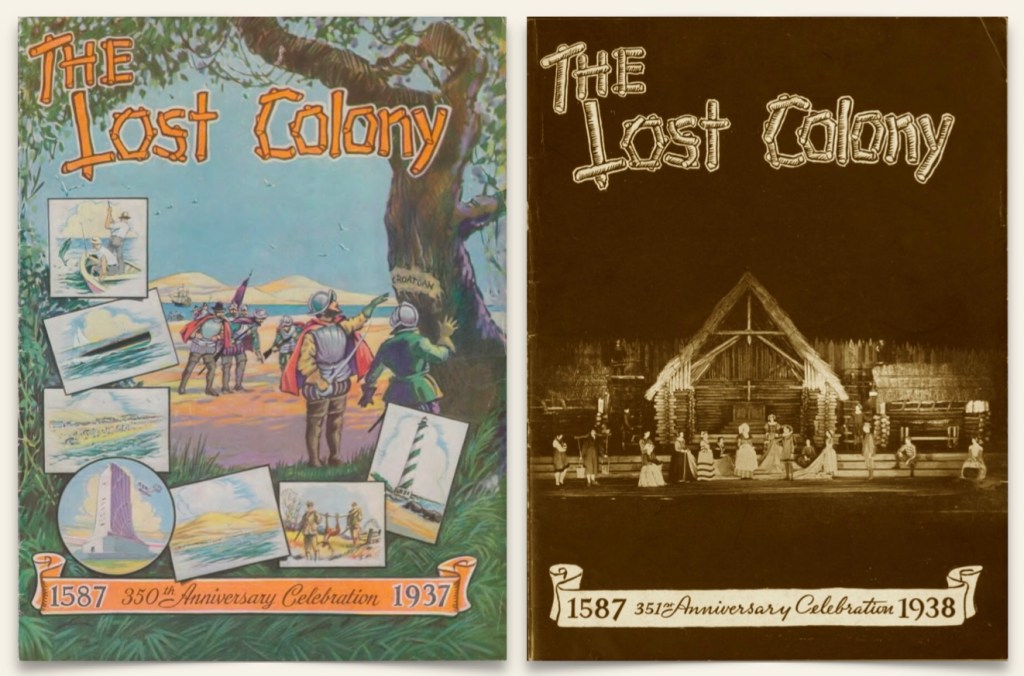

Lost Colony Museum on Hatteras Island

Most recently, Dawson revealed that “archaeologists found ‘buckets’ of hammer scale, a leftover material from blacksmithing… ‘This is showing a presence of the English working metal and living in the Indian Village for decades —We’re finding this whole metalworking workshop on the site and natives didn’t do that…’ and ‘The Lost Colony is a marketing campaign that started in 1937 and it created this myth of a colony that vanished, and none of that is real…” (WHRO Public Media)

The marketing campaign from 1937 was a play — We learned that, “The Lost Colony is an historical outdoor drama, written by American Paul Green and produced since 1937 in Manteo, North Carolina… The play was written during the Great Depression by Paul Green, who had earlier won the Pulitzer Prize for drama.”

“The drama attracted enough tourists to stimulate the economy of Roanoke Island and the Outer Banks of North Carolina. Their hotels, motels, and restaurants thrived despite the bleak depression economy. The village of Manteo renamed its streets after historic figures in the drama. Originally intended for one season, the drama was produced again the following year and has since become a North Carolina tradition. Since 1937, more than four million visitors have seen it.”

Mystery sells. Mystery solved. (5)

(Image courtesy of the Island Institute, The Working Waterfront).

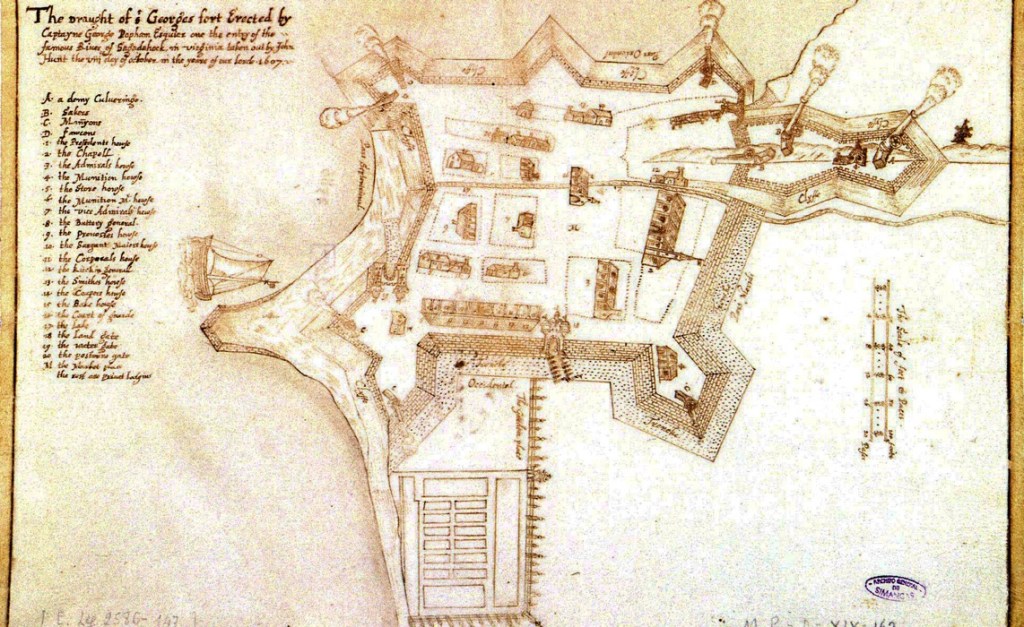

The Popham Colony, 1607-1608

“The Popham Colony—also known as the Sagadahoc Colony — was a short-lived English colonial settlement in North America. It was established in 1607 and was located in the present-day town of Phippsburg, Maine, near the mouth of the Kennebec River. It was founded a few months after its more successful rival, the colony at Jamestown. (See Jamestown below).

Popham was a project of the Plymouth Company, which was one of the two competing parts of the proprietary Virginia Company that King James chartered in 1606 to raise private funds from investors in order to settle Virginia. At the time, the name Virginia applied to the entire east coast of North America from Spanish Florida to New France in modern-day Canada. That area was technically under the claim of the Spanish crown, but was not occupied by the Spanish.

The colony lasted just 14 months. It is likely that the failure of the colony was due to multiple problems: the lack of financial support after the death of Sir John Popham, the inability to find another leader, the cold winter, and finally the hostility of both the native people and the French. The settlement of New England was delayed until it was taken up by refugees instead of adventurers.” (Wikipedia) (6)

(Image courtesy of the National Park Service).

The Jamestown Settlement, 1607

In the beginning, the Jamestown Colony was yet another English disaster. On May 14, 1607, a group of roughly 100 members of the Virginia Company founded the first permanent English settlement in North America on the banks of the James River. (Note: The two key words here are English and permanent). It was “known variously as James Forte, James Towne and James Cittie, the new settlement initially consisted of a wooden fort built in a triangle around a storehouse for weapons and other supplies, a church and a number of houses.

The settlers… suffered greatly from hunger and illnesses like typhoid and dysentery, caused from drinking contaminated water from the nearby swamp. Settlers also lived under constant threat of attack by members of local Algonquian tribes, most of which were organized into a kind of empire under Chief Powhatan.

An understanding reached between Powhatan and John Smith led the settlers to establish much-needed trade with Powhatan’s tribe by early 1608. Though skirmishes still broke out between the two groups, the Native Americans traded corn for beads, metal tools and other objects (including some weapons) from the English, who would depend on this trade for sustenance in the colony’s early years.

After Smith returned to England in late 1609, the inhabitants of Jamestown suffered through a long, harsh winter known as “The Starving Time,” during which more than 100 of them died. Firsthand accounts describe desperate people eating pets and shoe leather. Some Jamestown colonists even resorted to cannibalism. George Percy, the colony’s leader in John Smith’s absence, wrote:

“And now famine beginning to look ghastly and pale in every face that nothing was spared to maintain life and to do those things which seem incredible, as to dig up dead corpse out of graves and to eat them, and some have licked up the blood which hath fallen from their weak fellows.”

In the spring of 1610, just as the remaining colonists were set to abandon Jamestown, two ships arrived bearing at least 150 new settlers, a cache of supplies and the new English governor.” (History.com)

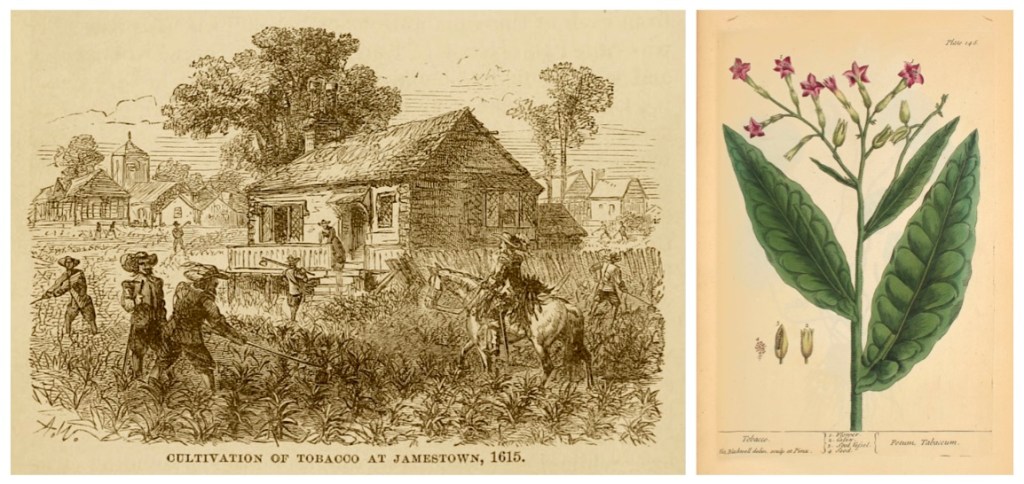

Tobacco became Virginia’s first profitable export —

“A period of relative peace followed the marriage in April 1614 of the colonist and tobacco planter John Rolfe to Pocahontas, a daughter of Chief Powhatan who had been captured by the settlers and converted to Christianity. (According to John Smith, Pocahontas had rescued him from death in 1607, when she was just a young girl and he was her father’s captive.) Thanks largely to Rolfe’s introduction of a new type of tobacco grown from seeds from the West Indies, Jamestown’s economy began to thrive.

This “genre artwork” lithograph is typical for the period with its historical inaccuracies. The scene is idealized; there are no mountains in Tidewater Virginia, for example, and the Powhatans lived in thatched houses rather than tipis.

In 1619, the colony established a General Assembly with members elected by Virginia’s male landowners; it would become a model for representative governments in later colonies. That same year, the first Africans (around 50 men, women and children) arrived in the English settlement; they had been on a Portuguese slave ship captured in the West Indies and brought to the Jamestown region. They worked as indentured servants at first (the race-based slavery system developed in North America in the 1680s) and were most likely put to work picking tobacco.” (History.com)

Observation: A number of historians actually document that this event — Tobacco fueled English colonization, the use of slave labor — was the true beginning of slavery for the future United States, despite the indentured servitude designation written above. (Historic Jamestowne).

“Also in 1619, the Virginia Company recruited and shipped over about 90 women to become wives and start families in Virginia, something needed to establish a permanent colony. Over one hundred women, who brought or started families, had arrived in prior years, but 1619 was when establishing families became a primary focus.” (Historic Jamestowne)

Wikipedia points out this grim fact about colonial life during this period, “Of the 6,000 people who came to the [Jamestown] settlement between 1608 and 1624, only 3,400 survived.” (7)

Captain John Smith and His Love of Maps

Captain John Smith was an ardent and skilled map maker. He published two maps in England of the east coast of North America, one in 1612, and the other in 1614. These early actions had much impact in how North America was eventually settled. Author Peter Firstbrook wrote in his book, A Man Most Driven: Captain John Smith, Pocahontas and the Founding of America —

“When Smith was mapping New England, the English, French, Spanish and Dutch had settled in North America. Each of these European powers could have expanded, ultimately making the continent a conglomerate of similarly sized colonies. But, by the 1630s, after Plymouth and the Massachusetts Bay Colony were established, the English dominated the East Coast—in large part, Firstbrook claims, because of Smith’s map, book and his ardent endorsement of New England back in Britain.”

“Were it not for his authentic representation of what the region was like, I don’t think it would be anywhere near as popular,” says Firstbrook. “He was the most important person in terms of making North America part of the English speaking world.” (Smithsonian)

Although our ancestors at Plymouth may have felt they were isolated in a new world of mostly Native Peoples, they were in fact part of an incredibly complex and inter-connected European network of trade and ideas. (8)

Following are the footnotes for the Primary Source Materials,

Notes, and Observations

Preface — Show Me The Money

(1) — one record

First Wave of European Colonization

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_wave_of_European_colonization

Note: For the text.

England Finally Gets In The Game

(2) — five records

National Geographic

Roanoke Wasn’t America’s Only Lost Colony

by Matthew W. Chwastyk

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/article/lost-colony-roanoke-virginia-mystery-map-interactive

Note: For the Colonial Pursuits map from the June 2018 issue.

Colonial Foundations

The Virginia Colony, Early 1600s

by Miles Hodges

https://spiritualpilgrim.net/02_America_The-Covenant-Nation/01_Colonial-Foundations/01c_Virginia.htm

Note: For the text.

List of North American Settlements by Year of Foundation

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_North_American_settlements_by_year_of_foundation

La Virgenia Pars — map of the E coast of N America from Chesapeake bay to the Florida Keys, with arms of Sir Walter Raleigh, English vessels, dolphins, fish, whales and sea-monsters

by John White, circa 1585-1593

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1906-0509-1-2

Note: For the map image.

(HVGIB)

How Virginia Got Its Boundaries

by Karl R. Phillips

http://www.virginiaplaces.org/boundaries/boundaryk.html

Note: For the text.

King James I and the Virginia Company of 1606

(3) — nine records

Painting of James VI and I Wearing the Jewel Called the Three Brothers in His Hat, circa 1605

by (after) John de Critz

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Portrait_of_James_I_of_England_wearing_the_jewel_called_the_Three_Brothers_in_his_hat.jpg

Note: For the portrait of James I.

(HVGIB)

How Virginia Got Its Boundaries

by Karl R. Phillips

http://www.virginiaplaces.org/boundaries/boundaryk.html

Note: For the text.

Colonial Foundations

The Virginia Colony, Early 1600s

by Miles Hodges

https://spiritualpilgrim.net/02_America_The-Covenant-Nation/01_Colonial-Foundations/01c_Virginia.htm

Note: For the text.

Virginia Company

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virginia_Company

Note: For the text, map, and images.

Plymouth Company

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plymouth_Company

Note: For the text.

Virginia Company of London

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virginia_Company_of_London

Note: For the text and images.

Virginia Museum of History & Culture

Virginia Company of London

https://virginiahistory.org/learn/virginia-company-london

Note: For the text and images.

University of Glasgow

Special Collections of the Glasgow University Library

Americana

https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/library/files/special/exhibns/Americana/17th_century.html

Note: For image, The New Life of Virginea.

Jamestown, Virginia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jamestown,_Virginia

Note: For the text.

The Roanoke Colony, 1587 — ?

(4) — eleven records

Walter Raleigh (portrait)

by William Segar

https://www.worldhistory.org/Walter_Raleigh/

Note: For his portrait.

Encyclopædia Britannica

Elizabeth I, Queen of England (portrait)

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Elizabeth-I

Note: For her portrait.

(HVGIB)

How Virginia Got Its Boundaries

by Karl R. Phillips

http://www.virginiaplaces.org/boundaries/boundaryk.html

Note: For the text.

Walter Raleigh

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Walter_Raleigh

Note: For the text.

The Lost Colony,

by William Ludwell Sheppard.

Illustration from the 1876 textbook, A Popular History of the United States

by William Cullen Bryant, circa 1876

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:A_popular_history_of_the_United_States_-_from_the_first_discovery_of_the_western_hemisphere_by_the_Northmen,_to_the_end_of_the_first_century_of_the_union_of_the_states;_preceded_by_a_sketch_of_the_(14781233224).jpg

Notes: “This image depicts John White returning to the Roanoke Colony in 1590 to discover the settlement abandoned. A pallisade had been constructed since White’s departure in 1587, and the word “CROATOAN” was found carved near the entrance. White explained to his men that this was a prearranged signal to indicate that the colony had relocated, but was unable to search Croatoan Island for further information.”

Roanoke Colony

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roanoke_Colony

Note: For the illustration and text.

National Geographic

It Was America’s First English Colony. Then It Was Gone.

by Andrew Lawler

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/article/lost-colony-roanoke-history-theories-croatoan

Note: For the text and illustrations.

(HVGIB)

How Virginia Got Its Boundaries

by Karl R. Phillips

http://www.virginiaplaces.org/boundaries/boundaryk.html

Note: For the text.

The Roanoke Map Collage —

The British Museum

La Virginea Pars map

by John White, circa 1585-1590

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1906-0509-1-3

and

The First Colony Foundation

Hidden Images Revealed on Elizabethan Map of America

by Brent Lane

https://www.firstcolonyfoundation.org/news/hidden-images-revealed-elizabethan-map-america/

Note: Detail of “La Virginea Pars…” by John White showing the area of one of two paper patches (the northern patch) stuck to the map.

and

History.com

John White

By Artist Unknown

https://www.history.com/topics/colonial-america/john-smith

Note: For the John White portrait.

Roanoke in the Popular Imagination

(5) — seven records

Roanoke Colony

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roanoke_Colony

Note: For the text.

History of the Colonization of The United States

by George Bancroft, circa 1841

https://archive.org/details/historyofcoloniz00banc/page/n7/mode/2up

Book pages: 36-45, Digital pages: 66-74/568

Note: For the text and images.

National Geographic

It Was America’s First English Colony. Then It Was Gone.

by Andrew Lawler

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/article/lost-colony-roanoke-history-theories-croatoan

Note: For the anecdote about John Smith and stories of the Roanoke Colony.

WHRO Public Media

New Artifacts on Hatteras Point to the Real Fate of The Lost Colony

by Lisa Godley

https://www.whro.org/arts-culture/2025-01-20/new-artifacts-on-hatteras-point-to-the-real-fate-of-the-lost-colony?utm_source=enewsletter&utm_medium=enews&utm_term=text&utm_campaign=241213

Note: For the text.

The Lost Colony (play)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Lost_Colony_(play)

File:Playbill for the 1937 Federal Theatre Project production of Samuel Selden and Paul Green’s The Lost Colony.pdf

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Playbill_for_the_1937_Federal_Theatre_Project_production_of_Samuel_Selden_and_Paul_Green’s_The_Lost_Colony.pdf

Note: For the playbill cover artwork for the first year of the production of the play.

and

Library of Congress

The Lost Colony

Playbill from the 1938 production

by Paul Green and Samuel Selden

The Federal Theatre Project

https://www.loc.gov/resource/music.musftpplaybills-200221035/?st=gallery

Note: For the playbill cover artwork for the second year of the production of the play.

The Popham Colony, 1607-1608

(6) — two records

Island Institute, The Working Waterfront

Mysteries of Maine’s First European Colony

by Phil Showell

https://www.islandinstitute.org/working-waterfront/mysteries-of-maines-first-european-colony/

Note: For the text, and John Hunt’s map of Fort St George (Popham Colony).

Popham Colony

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Popham_Colony

Note: For the text.

The Jamestown Settlement, 1607

(7) — twelve records

The National Park Service

1492–1800 Colonial & Early National Period

https://www.nps.gov/subjects/fossils/1492-1800-colonial-early-national-period.htm

Note: For this painting, “Jamestown settlement on the James River, Virginia,” as it may have been in 1615, by Sidney E. King.

History.com

Jamestown Colony

https://www.history.com/topics/colonial-america/jamestown

Note: For the text.

Encyclopedia Virginia

Powhatan (d. 1618)

https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/powhatan-d-1618/

Note: For image of Captain John Smith.

and

Legends of America

Chief Powhatan – Wahunsunacawh

https://www.legendsofamerica.com/chief-powhatan/

Note: For the image of Chief Powhatan.

and

File:Powhatan john smith map.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Powhatan_john_smith_map.jpg

Note: Map detail described “Powhatan held this state & fashion when Capt. Smith was delivered to him prisoner 1607”. Cropped part of John Smith’s Map of Virginia used in various publications, first in 1612.

Note: For the map detail.

File:Pocahontas Saving the Life of Capt. John Smith – New England Chromo. Lith. Co. LCCN95507872.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pocahontas_saving_the_life_of_Capt._John_Smith_-_New_England_Chromo._Lith._Co._LCCN95507872.jpg

Note: For the lithographic print.

For the tobacco illustrations —

A School History of the United States,

from The Discovery of America to the Year 1878

by David B. Scott

https://archive.org/details/schoolhistoryofu00scot/page/40/mode/2up

Bool page: 40, Digital page: 40/431

Note: For tobacco crop illustration.

and

NIH, The National Institutes of Health

National Library of Medicine

Petum Tabaccam, Plate 14B

https://circulatingnow.nlm.nih.gov/2016/04/14/some-of-the-most-beautiful-herbals/page14b/

Note: For the tobacco plant illustration.

A Short History of Jamestown

https://www.nps.gov/jame/learn/historyculture/a-short-history-of-jamestown.htm

Note: Regarding brides and families, 1619.

Historic Jamestowne

A Short History of Jamestown

https://www.nps.gov/jame/learn/historyculture/a-short-history-of-jamestown.htm

Note: For the text.

Jamestown, Virginia 1660s (painting)

https://keithrocco.com/product/jamestown-virginia-1660s/

Note: For his painting image of Jamestown.

Jamestown, Virginia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jamestown,_Virginia

Note: For text regarding statistical survivals.

Captain John Smith and His Love of Maps

(8) — two records

Smithsonian Magazine

John Smith Coined the Term New England on This 1616 Map

by Megan Gambino

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/john-smith-coined-the-term-new-england-on-this-1616-map-180953383/

Note: For the text.

Virtual Jamestown

Virginia (map)

by John Smith, circa 1612

http://www.virtualjamestown.org/jsmap_large.html

Note: Virginia was originally published (separately) in London in 1612, and then in the 1612 Oxford publication of John Smith’s A Map of Virginia: With a Description of the Countrey [sic], the Commodities, People, Government and Religion.

Note: For the map image.