This is Chapter Five of seven. In this chapter we are going to share some of the knowledge we’ve gained about what it was like to live in the new ‘Plimouth’ Plantation, but first an interesting history that is quite literally, about a rock.

But now, God knows, Anything Goes!

Times have changed / And we’ve often rewound the clock / Since the Puritans got the shock / When they landed on Plymouth Rock

If today / Any shock they should try to stem / ’Stead of landing on Plymouth Rock / Plymouth Rock would land on them!

In 1934, Cole Porter wrote the classic Broadway musical Anything Goes!, and it was quite an enormous hit with the Depression Era audiences. In fact, some of those catchy songs are still popular to this day. However, he got the introductory details in the lyrics just a little off in the title song.

The Puritans didn’t land at Plymouth Rock. Our ancestors the Pilgrims did — or did they?

When you first lay eyes on Plymoth Rock, you can’t help but think, Is that all there is? (Cue singer Peggy Lee). It’s actually just pretty much a boulder. Even when you take a hopeful photograph wishing that through the magic of your camera, it will be… somehow more photogenic. It still ends up looking underwhelming — just like a rock from somebody’s yard down the street.

There are historical reasons for this. (1)

The Real Story of Behind Plymouth Rock

“There’s the inconvenient truth that no historical evidence exists to confirm Plymouth Rock as the Pilgrims’ steppingstone to the New World. Leaving aside the fact that the Pilgrims first made landfall on the tip of Cape Cod in November 1620 before sailing to safer harbors in Plymouth the following month, William Bradford and his fellow Mayflower passengers made no written references to setting foot on a rock as they disembarked to start their settlement on a new continent.

It wasn’t until 1741—121 years after the arrival of the Mayflower—that a 10-ton boulder in Plymouth Harbor was identified as the precise spot where Pilgrim feet first trod. The claim was made by 94-year-old Thomas Faunce, a church elder who said his father, who arrived in Plymouth in 1623, and several of the original Mayflower passengers assured him the stone was the specific landing spot. When the elderly Faunce heard that a wharf was to be built over the rock, he wanted a final glimpse. He was conveyed by chair 3 miles from his house to the harbor, where he reportedly gave Plymouth Rock a tearful goodbye. Whether Faunce’s assertion was accurate oral history or the figment of a doddering old mind, we don’t know.

By the 1770s, just a few years after Faunce made his declaration, Plymouth Rock had already become a tangible monument to freedom. As a revolutionary fever swept through Plymouth in 1774, some of the town’s most zealous patriots sought to enlist Plymouth Rock in the cause. With 20 teams of oxen at the ready, the colonists attempted to move the boulder from the harbor to a liberty pole in front of the town’s meetinghouse. As they tried to load the rock onto a carriage, however, it accidentally broke in two. The bottom portion of Plymouth Rock was left embedded on the shoreline, while the top half was moved to the town square.

On July 4, 1834, Plymouth Rock was on the move again, this time a few blocks north to the front lawn of the Pilgrim Hall Museum. And once again, the boulder had a rough ride. While passing the courthouse, the rock fell from a cart and broke in two on the ground. The small iron fence encircling Plymouth Rock did little to discourage the stream of souvenir seekers from wielding their hammers and chisels to get a piece of the rock. (Even today, chips off the old block are strewn across the country in places such as the Smithsonian Institution and the Plymouth Church in Brooklyn.)

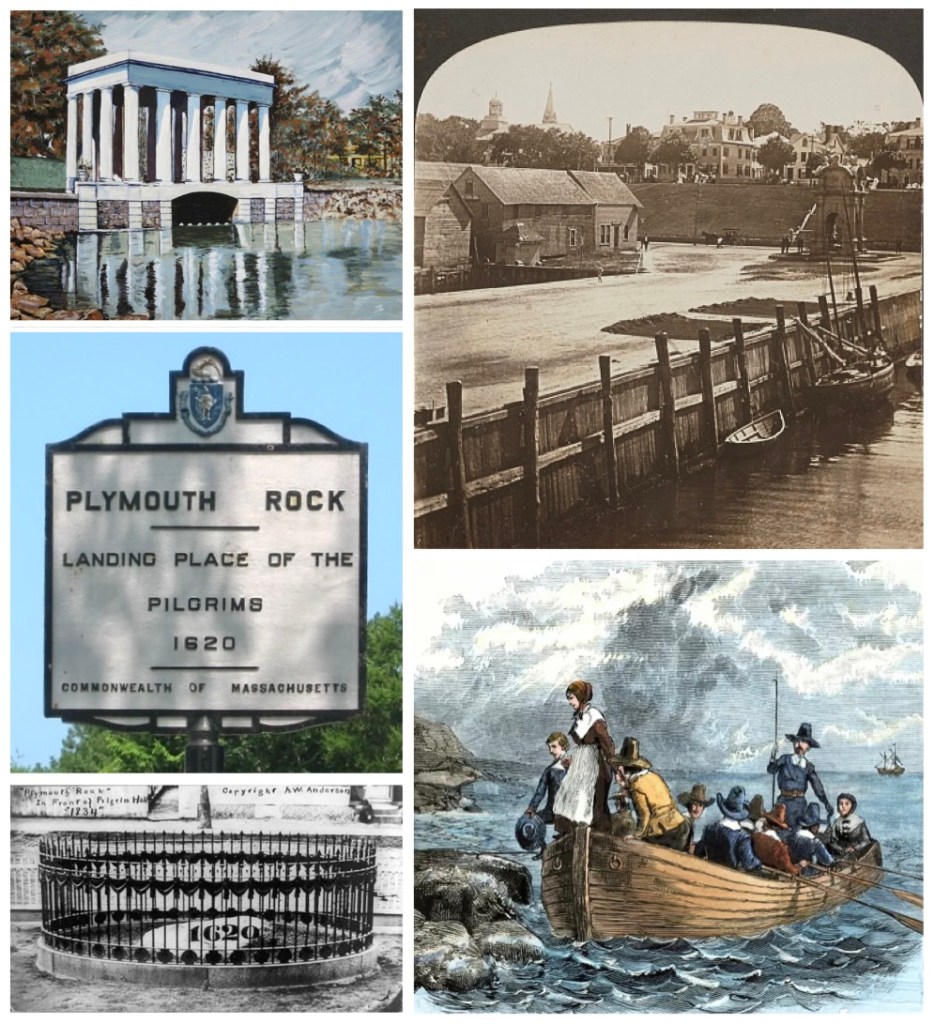

Clockwise from the top left: The painting Memorial Housing the Plymouth Rock, (which was built circa 1920), the wharf which was built over the Rock, circa 1860s, a lithographic print of passengers arriving, Plymouth Rock in front of Pilgrim Hall, circa 1834, (note the painted numerals) and from the Historical Marker Database, the Plymouth Rock Marker. (See footnotes).

Finally, in 1880, at the same time that an America torn asunder by the Civil War was stitching itself back together, the top of Plymouth Rock was returned to the harbor and reunited with its base. The date ‘1620’ was carved on the stone’s surface, replacing painted numerals.

In conjunction with the 300th anniversary of the Pilgrims’ arrival, Plymouth’s Rock’s current home, which resembles a Roman temple, was constructed. The boulder now rests on a sandy bed 5 feet below street level, encased in an enclosure like a zoo animal. Given all the whittling and the accidents, Plymouth Rock is estimated to be only a third or half of its original size, and only a third of the stone is visible, with the rest buried under the sand. A prominent cement scar is a reminder of the boulder’s tumultuous journeys around town.” (History.com) (2)

Comment: Was Plymouth Rock ever really this big? Or was the painter Henry Bacon just inspired?

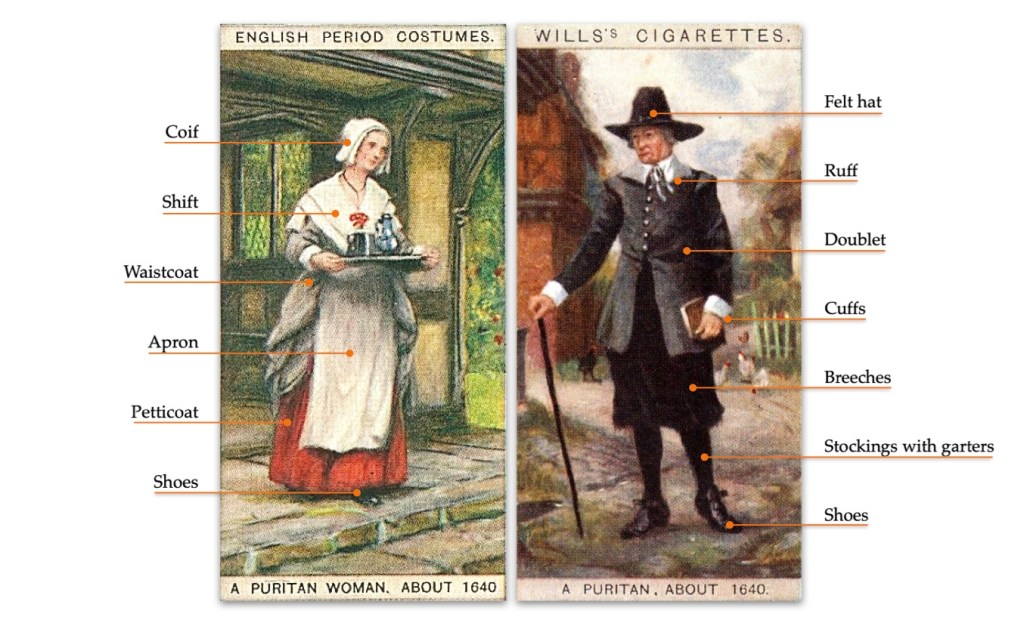

English Clothing in the 1620s: Not What You Think

“Many people think the Pilgrims always wore black clothes. This may be because in many images of the time, people are shown wearing black clothes. This is because in the 1620s, the best clothes were often black, and people usually had their portraits painted while wearing their best clothes. It was not easy to dye cloth a solid, long-lasting black. It took a great deal of skill. People kept clothes made of such beautiful, expensive cloth for special occasions. Everyday clothes were made of many colors. Brown, brick red, yellow and blue were common. Other clothes were made of cloth that was not dyed. These clothes were gray or white, the natural color of the cloth.” (Plimoth Pautuxet)

The Pilgrims were not Puritans, even though they are sometimes labeled as such

by writers and artists from the past. (They just dressed similarly).

A Puritan Woman, About 1640 and A Puritan Man, About 1640.

These cards are from WD & HO Wills, a British tobacco company founded in 1786.

(The series is from 1929, English Period Costumes).

Note: The man’s clothing would likely have been more colorful, despite the fact that many Victorian era illustrators have frequently portrayed the Pilgrims as wearing black.

“Men wore a short jacket called a doublet, which was attached to breeches (which are knee-length pants), to form a suit. Usually they were made of wool cloth or linen canvas. A felt hat often completed the outfit. At the time when the Pilgrims first arrived in Massachusetts, colors were fashionable, and the colonists wore various hues. The wardrobe of colonist William Brewster, for example, included a pair of green trousers and a violet-colored coat.

Women colonists wore elaborate multi-layered outfits: a corset, multiple petticoats, stockings, a dress over those items, and a waistcoat or apron. They also wore linen caps called coifs over their hair, and felt hats as well.” (WordPress, George Soule History) (3)

The Everyday Life of The Settlers

Historian Carla Pestana shares her thoughts on their everyday lives with this story, and reflects on how the world they lived in, was quickly changing:

“One thing I got fascinated with was the everyday reality of the settlers’ lives. In the book, I tell the story of a man named Thomas Hallowell who gets called before the grand jury in Plymouth in 1638 because he’s wearing red stockings. The reason why his neighbors call him on this, is that they know he doesn’t own red stockings and has no honest way to acquire them. So they think it needs to be looked into. When he’s called into court, he immediately confesses, yes, I was up in the very new town of Boston. I saw these stockings laying over a windowsill, drying, and I pocketed them, and brought them back to Plymouth, and put them on, and wore them in front of my neighbors, who knew I didn’t have them.

That story tells you so much. The neighbors knew exactly what clothes he had, because clothes were really scarce and valuable. The materials to make clothing were not locally available, at first, and so it all has to be imported, which means that it’s expensive. Mostly they have to make do with what they have.

There were lots of references in letters, accounts, and even in the court records about people and their clothing, and about having to provide a suit of clothes to somebody, or having some shoes finally arrive on a ship, and what they’re able to do because the shoes have arrived. You’d think, shoes arrived, no big deal, but the shoes don’t just make themselves!

Cloth is coming in, and it’s being traded with Native hunters, and it’s being used by local people to make clothes. They try to get sheep, so they can have wool and start making woolen cloth. All of this trade is connecting them to other places, where sheep are available, or skills are available, or the cloth is coming from, or the shoes are coming from. That little story about this man’s stockings really tells us so much.

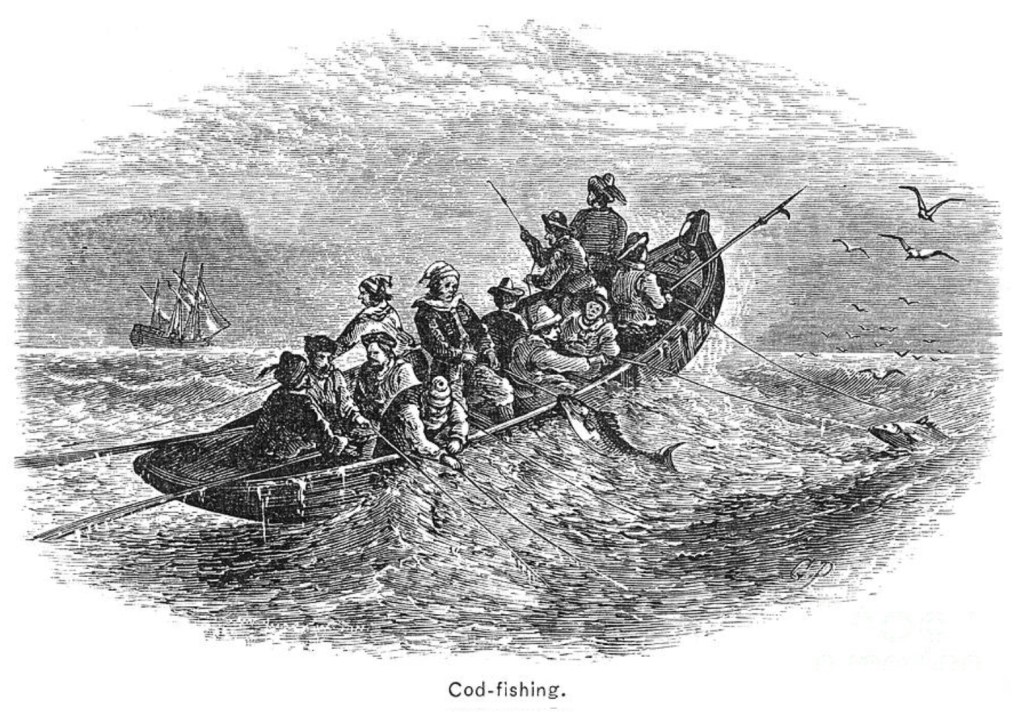

Changes were happening in the wider world, of which they were part. English people are in Virginia and Bermuda. The English are going in and out of the Caribbean all the time, and thinking about setting up settlements down there. Fisherman operating off the Grand Banks and in the northern fisheries are always stumbling into Plymouth. Then shortly after Plymouth, the New Amsterdam [Manhattan Island] colony was founded so English have these not-too-distant European neighbors from the Netherlands. French fishing boats are constantly in the region, so there’s all kinds of activity, and people coming and going.

(Image courtesy of Granger Art On Demand).

Almost immediately after Plymouth is founded, other peoples from England say, ‘Well, we can go there, too. We don’t need to be part of Plymouth, but we can go to that region, and actually mooch off of Plymouth for a while for food and supplies, and then go set up a trading post somewhere else.’ ” (Smithsonian) (4)

New England’s Great Migration Had Started

The eventual success of the Plimoth Plantation caught the attention of many investors and immigrants back home in England. The inset detail (below) is excerpted from the famous 1676 Map of New York and New England by John Speed of London. (And no, that dark spec next to the ‘New Plymouth’ name is not the Plymouth Rock before it went on all of its adventures).

As part of The Great Migration, a map like this, with all of the various harbors already named, helped familiarize people with this strange new world they had been hearing about.“It depicts the territories acquired by the British with the capture of New Amsterdam in 1664, which changed European influence in the colonies from the Dutch to the English. It is the first appearance of the name Boston, and the first map to use the term New York for both Manhattan and the colony.”

from A Map of New England and New York, by John Speed, circa 1676.

(Image courtesy of Raremaps.com).

“The Great Migration Study Project uses 1620 — the date of the arrival of the Mayflower — as its starting point. The peak years lasted just over ten years — from 1629 to 1640, years when the Puritan crisis in England reached its height.

Motivated primarily by religious concerns, most Great Migration colonists traveled to Massachusetts in family groups. In fact, the proportion of Great Migration immigrants who traveled in family groups is the highest in American immigrant history. Consequently, New England retained a normal, multi-generational structure with relatively equal numbers of men and women. At the time they left England, many husbands and wives were in their thirties and had three or more children, with more yet to be born.

Great Migration colonists shared other distinctive characteristics. New Englanders had a high level of literacy, perhaps nearly twice that of England as a whole. New Englanders were highly skilled; more than half of the settlers had been artisans or craftsmen. Only about seventeen percent came as servants, mostly as members of a household.” (American Ancestors) (5)

(Image courtesy of Dreamstime).

Let’s Put A Pin In That (Place) Name!

We have come across some name variations about the place where the Pilgrims established their colony, which seem to cause a bit of confusion. We believe that these names depend upon the era in which the history was written, so we have sorted them out a bit.

Plymouth

This is the location of the eventual (future) town on Cape Cod Bay where the Pilgrims established their settlement.

Plimoth Plantation, or Plymouth Plantation

This is name with which Governor William Bradford described their settlement in his journal Of Plimoth Plantation. This old-fashioned spelling was soon supplanted with the more modern spelling: Plymouth Plantation.

Plimoth Colony, or Plymouth Colony

Whether the Name is spelled as Plimoth, or Plymouth depends upon your source material, (and your computer’s fussy spell-check programming). They are the same place, just not the same spelling.

New Plimoth, or New Plymouth

Again, the same place. Some people have assumed that the Pilgrims named Plymouth after the English port city they knew. Actually, John Smith had already named the area New Plimouth on his 1616 map. See the chapter, The Pilgrims — A Mayflower Voyage.

(Image courtesy of Wikipedia).

Plimoth Patuxet

This is the name of the museum and present day historical (replica village) site near the town of Plymouth. It is viewed as a more accurate representation of the cultures that co-existed at that time. “For the 12,000 years that the Wampanoag lived in and around what is now Plymouth, they called the land Patuxet, meaning ‘place of running water’ in the Wampanoag language. This land that is both Patuxet and Plymouth speaks to the emergence of an Indigenous-English hybrid society that existed here — in conflict and in collaboration – in the 17th century.” (See footnotes, The Enterprise) (6)

William Bradford’s 1620 Sketch of Plymouth

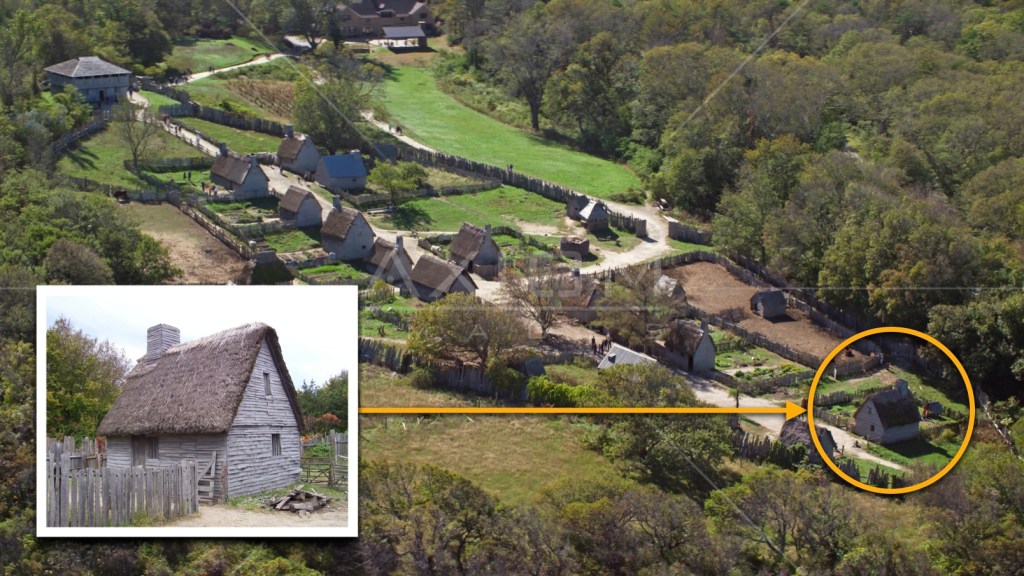

For our two Pilgrim ancestors — George Soule and Edward Doty — we have only been able to discern where the Soule family home was specifically located. We started with William Bradford’s 1620 Sketch of Plymouth, upon which he noted the two primary roads: one labeled the Streete, and the other the High Way. On this sketch, he also indicated where some homes were built, or intended to be built, since it was Winter time.

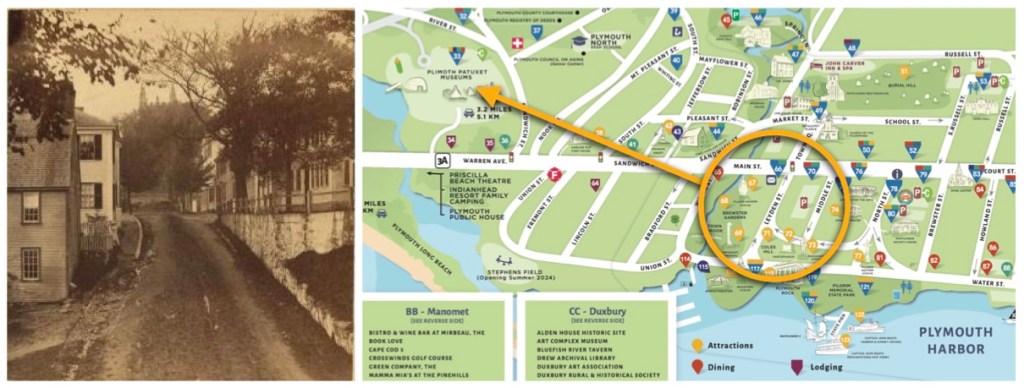

The second map is from the 19th century. If you look closely, you can see that First Street (the Streete), had a name change to Leyden Street. This happened in 1823, when it was renamed in honor of Leiden, Holland.

The third sketch is from the 20th century and is an aerial view of the Plymouth Plantation* for a November 1966 newspaper article in the Arkansas Gazette (Little Rock, Arkansas). The George Soule home is tucked into the upper corner.

*Now known as the Plimoth Patuxet Museum, it opened in 1947.

Lastly, the image shown below at the lower right, appears as if it is from the mid-20th century. Note how several more homesites are accounted for, which earlier documents had not yet indicted. This brings us to any interesting point — it was a big challenge to work out exactly where the Soule house was, because all of these maps / had different authors / in different eras / with different purposes. Even the modern aerial photograph below does not account for a couple of new home additions to the Plimoth Patuxet site. (7)

Leyden Street

In the last few years, archeologists have determined that the original location of Plimoth Plantation was likely Leyden Street in the present town of Plymouth, Massachusetts.

From the article See Plymouth, “The Pilgrims began laying out the street before Christmas in 1620 after disembarking from the Mayflower. The original settlers built their houses along the street from the shore up to the base of Burial Hill where the original fort/gun platform building was located, and now is the site of a cemetery and First Church of Plymouth.

Leyden Street is a street in Plymouth, Massachusetts that was created in 1620 by the Pilgrims, and claims to be the oldest continuously inhabited street in the Thirteen Colonies of British America. It was originally named First Street, …named Leyden Street in 1823.” (See Plymouth) (8)

If you recall from previous chapters, we learned that the British nobility were interested in developing these American colonies so that they could extract resources and bring those resources back to Europe to make money — and — the Pilgrims also had a responsibility to pay off their debts to the underwriters, who had financed their Mayflower voyage.

This transactional relationship required our ancestors to learn and develop new skills to prosper in this, their new home. They owe much of this success to the help of The Native Peoples.

Following are the footnotes for the Primary Source Materials,

Notes, and Observations

But now, God knows, Anything Goes!

(1) — three records

Anything Goes! (lyrics)

by Cole Porter

https://www.allmusicals.com/lyrics/anythinggoes/anythinggoes.htm

Ella Fitzgerald – Anything Goes (Verve Records 1956)

We believe that the best version of this song, is this one.

Click on the link to listen:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8NTO2n35Xo0

Library of Congress

Plymouth Rock, Plymouth, Mass. digital file from original

https://www.loc.gov/resource/stereo.1s13324/

Note: For the stereo scope image, circa 1925.

Plymouth Rock

(2) — eight records

History.com

The Real Story Behind Plymouth Rock

by Christopher Klein

https://www.history.com/news/the-real-story-behind-plymouth-rock

Note: For much of the text. Thanks Chris!

Colonial Quills

Saving Plymouth Rock

Massacusetts, Landing at Plymouth 1620

https://colonialquills.blogspot.com/2014/12/saving-plymouth-rock.html

Note: For the boat landing artwork.

The long history of Plymouth Rock in images,

with the five references which follow—

Memorial Housing the Plymouth Rock, Plymouth, Massachusetts

by E. Mote

https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/memorial-housing-the-plymouth-rock-plymouth-massachusetts-147875

Note: For the Roman temple-like image which houses the Plymouth Rock.

Library of Congress

Where the pilgrims landed, Plymouth Rock and Cole’s Hill, Plymouth, Mass., U.S.A.

https://www.loc.gov/item/2018649923/

Note: For the wharf image.

Library of Congress

Plymouth Rock, in front of Pilgrim Hall, ‘1834’ b&w film copy neg.

https://www.loc.gov/resource/cph.3b43231/

Note: For the painted 1620 numerals image.

Mediastorehouse.com

Mayflower passengers landing at Plymouth Rock, 1620

https://www.mediastorehouse.com/north-wind-picture-archives/american-history/mayflower-passengers-landing-plymouth-rock-1620-5877623.html

Note: For the disembarking passengers image.

The Historical Marker Database

1. Plymouth Rock Marker

https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=2896

Note: For the photograph.

The Landing of the Pilgrims

by Henry Bacon, circa 1877

File:The Landing of the Pilgrims (1877) by Henry A. Bacon.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Landing_of_the_Pilgrims_(1877)_by_Henry_A._Bacon.jpg

Note: For the painting image.

English Clothing in the 1620s: Not What You Think

(3) — five records

Plimoth Patuxet Museums

What to Wear?

English Clothing in the 1620s: Not What You Think

https://plimoth.org/for-students/homework-help/what-to-wear

Note: For the text.

George Soule History

Colony Lifestyle: Clothing

https://georgesoulehistory.wordpress.com/tag/mayflower/

Note 1: For the adapted text.

Note 2: Furthermore, it appear that this text above was adapted (or vice-versa), from:

What Did the Pilgrims Wear?

by Rebecca Beatrice Brooks

https://historyofmassachusetts.org/what-did-pilgrims-wear/

A Puritan Woman, About 1640 and A Puritan Man, About 1640.

These cards are from WD & HO Wills, a British tobacco company founded in 1786. (The series is from 1929, English Period Costumes).

Notes: Sources vary. For some of the text, see: https://tommies-militaria-and-collectables.myshopify.com/collections/wd-ho-wills-cigarette-cards For the card images; Google searches, such as: https://www.breakoutcards1.co.uk/a-puritan-woman-about-1640-24-english-period-costumes-1929-wills-card

The Everyday Life of The Settlers

(4) — three records

Smithsonian Magazine

Why the Myths of Plymouth Dominate the American Imagination

by Karin Wulf

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/why-myths-plymouth-dominate-american-imagination-180976396/

Note: For the text.

Interview of Samoset With The Pilgrims, book engraving

by Artist unknown, circa 1853

File:Interview of Samoset with the Pilgrims.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Interview_of_Samoset_with_the_Pilgrims.jpg

Note: For the image of Interview of Samoset With The Pilgrims

Granger Art On Demand

Woodcut engraving of 17th Century New England Cod-fishing

https://grangerartondemand.com/featured/cod-fishing-17th-century-granger.html

Note: For the illustration. Woodcut engraving, American, 1876.

New England’s Great Migration Had Started

(5) — three records

A Map of New England and New York

by John Speed, circa 1676

https://www.raremaps.com/gallery/detail/33805/a-map-of-new-england-and-new-york-speed

Note: For the map image.

Alexandre Antique Prints, Maps & Books

John Speed

A Map of New England and New York.

https://www.alexandremaps.com/pages/books/M8290/john-speed/a-map-of-new-england-and-new-york

Note: For the history of the John Speed map.“It depicts the territories acquired by the British with the capture of New Amsterdam in 1664, which changed European influence in the colonies from the Dutch to the English.. It is the first appearance of name Boston, and the first map to use the term New York for both Manhattan and the colony.”

Note: For the text.

American Ancestors

New England’s Great Migration

by Lynn Fetlock

https://www.americanancestors.org/new-englands-great-migration

Note: For the text.

Let’s Put A Pin In That (Place) Name!

(6) — four records

Dreamstime

A map of Plymouth, Massachusetts marked with a push pin

https://www.dreamstime.com/map-plymouth-massachusetts-marked-push-pin-image138326844

Note: For the map image.

Of Plymouth Plantation

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Of_Plymouth_Plantation#:~:text=Of%20Plymouth%20Plantation%20is%20a,the%20colony%20which%20they%20founded.

Note: For the text.

The Enterprise

Why was Plimoth Plantation changed to Plimoth Patuxet Museums?

https://eu.enterprisenews.com/story/news/history/2024/03/21/why-was-plimoth-plantation-changed-to-plimoth-patuxet-museums/72710390007/

Note: For the text.

File: Plimoth Plantation 2002.JPG

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Plimoth_Plantation_2002.JPG

Note: For contemporary photograph of the Plimoth Patuxet site.

William Bradford’s 1620 Sketch of Plymouth

(7) — six records

The Plymouth Colony Archive Project

Bradford’s 1620 Sketch of Plymouth

http://www.histarch.illinois.edu/plymouth/1620map.html

Note: For the map image.

Stagge-Parker Histories

George Soule 1600-1679

https://stagge-parker.blogspot.com/2009/05/george-soule.html

Note: For the map image.

File:Map of early Plymouth MA home lots.png

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Map_of_early_Plymouth_MA_home_lots.png#mw-jump-to-license

Note: For the map image.

Genealogy Bank

April 2022 Newsletter

Mayflower Descendants: Who’s Who, Part 14

by Melissa Davenport Berry

https://www.genealogybank.com/newsletter-archives/202204/mayflower-descendants-who’s-who-part-14

Note 1: For the map image.

Note 2: This map was originally published in “The Arkansas Gazette (Little Rock, Arkansas), 21 November 1966, page 25.” Original file name: arkansas-gazette-newspaper-1121-1966-plymouth-map.jpg

File:Plimoth Plantation farm house.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Plimoth_Plantation_farm_house.jpg

Note: 2009 photo of a Pilgrim House, (George Soule and Mary Soule’s) from Plimoth Plantation in Plymouth, Massachusetts, USA.

Note: For the Soule house image.

Axiom Images, Aerial Stock Photos

https://www.axiomimages.com/aerial-stock-photos/view/AX143_108.0000260

Note: Borrowed as the background image of the Plimoth Patuxet site > The Plimoth Plantation museum in Plymouth, Massachusetts Aerial Stock Photo AX143_107.0000194

Leyden Street

(8) — four records

Phys.org

Researchers find evidence of original 1620 Plymouth settlement

https://phys.org/news/2016-11-evidence-plymouth-settlement.html

Note: For the text.

Leyden Street

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leyden_Street

Note: For the stereographic photo and caption.

See Plymouth Massachusetts

Learn the True Story of the Pilgrims Along the Mayflower Trail —

Leyden Street

https://seeplymouth.com/news/learn-the-true-story-of-the-pilgrims-along-the-mayflower-trail/#:~:text=Leyden%20Street&text=After%20disembarking%20from%20the%20Mayflower,Thanksgiving%20was%20likely%20held%20nearby.

Note: For the text.

(Contemporary) Waterfront Visitors Center Map

https://seeplymouth.com/travel-guides/

Then use this link: https://seeplymouth.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/DP-001-24_2024_Map.pdf

Note: To document the location of the Plimoth Patuxet site in relation to contemporary downtown Plymouth, Massachusetts.