This is Chapter One of seven. We have written seven opening chapters about the history of The Pilgrims. They are structured around certain themes which frame the context(s) of the times within which these people lived. Think of them as a multi-lane highway where all lanes point in one direction — forward in time. At certain points, some lanes are more important than others, but together, they all inform the future, where we live.

In American culture, many people think that they have heard so much over the years about the Pilgrims, that there is nothing more they need to know. We disagree, because they haven’t met our family yet.

Two of our ancestors—

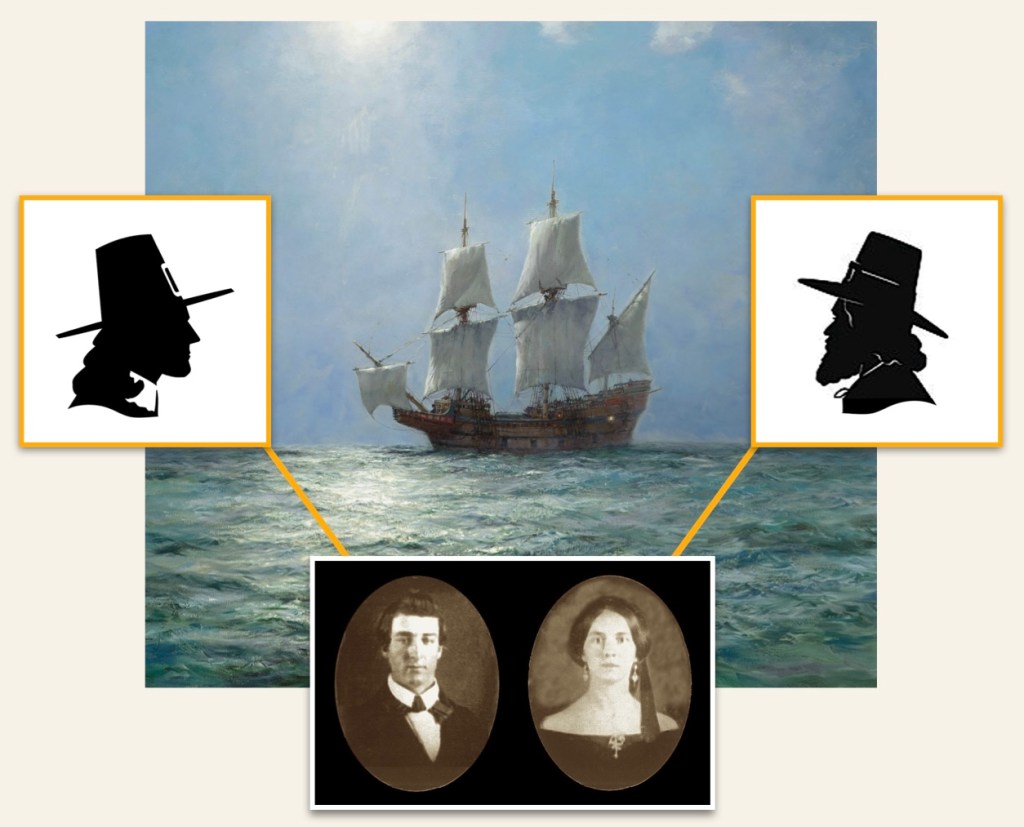

Pilgrim George Soule and Pilgrim Edward Doty, were on the 1620 voyage of the Mayflower. They and their fellow travelers, occupy a very prominent space in the collective consciousness of American mythology.

We highly recommend that these chapters be read before taking a look at The Soule Line, A Narrative, or The Doty Line, A Narrative. As with all of our ancestral families, this research honors them. Simply put, that is why we write and share this blog — because sometimes we have to go back, to go forward.

Atlantic Overture

When our Grandmother Lulu Mae (DeVoe) Gore died in 1975, we had to clean her house out of all its possessions. To be honest, although her home was quite neat and tidy, we just weren’t very efficient in getting rid of things. She had lived in that home for 55 years and most things that she owned meant something special to someone, so we took our time and distributed things carefully. We’re glad that we did.

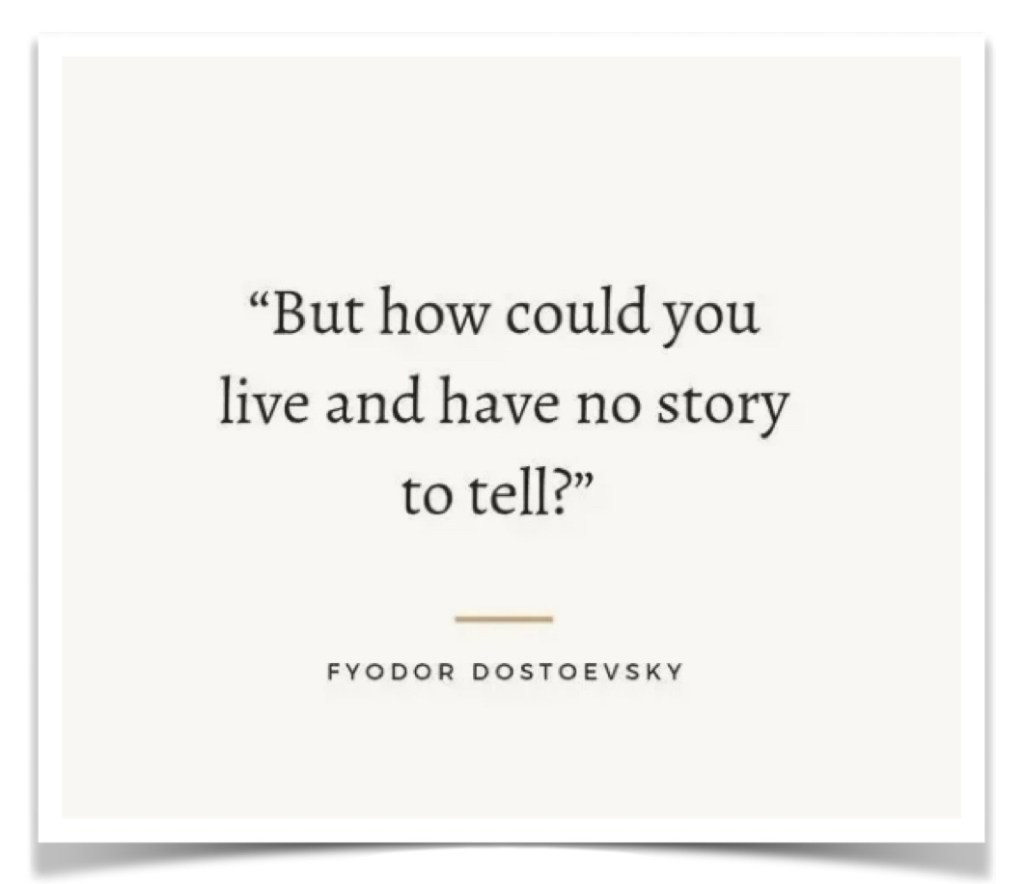

Lulu was the genealogist of the family, and from her research, there had been whispers going on that we had a Mayflower ancestor — we just didn’t know who exactly. Then this book was found tucked amongst others, next to her favorite sitting chair in her dining room. When flipping through the pages, we came across a notation that she had made in the index at some moment in the past.

Who was this person named Soule, George? Is this the ancestor who had been whispered about? Our mother Marguerite (Lulu’s daughter), then took over the genealogy work and completed the history which led her back to our ancestor, Pilgrim George Soule. After Marguerite passed on, Susan (Marguerite’s daughter), took up the mantle as the family genealogist and was able to develop many more family lines because the world had changed. (Much more information was now readily available on the internet). Susan determined that we also had an additional Mayflower ancestor, Pilgrim Edward Doty.

of the Mayflower. Both of these lines meet with our 2x Great Grandparents, through

the marriage of Peter A. Devoe (for Edward Doty), and Mary Ann Warner (for George Soule).

Background image, Isolation: The Mayflower Becalmed on a Moonlit Night, by Montague Dawson.

To understand some things about our Pilgrim ancestors, it is important to first understand the times in which they lived. For example,they were coming from the Old World (their known worldviews), to the New World (a strange, unknown place). (1)

The Columbian Exchange

Historically, this time period had an over-arching theme which came to be known as: “The Columbian Exchange is… [a]widespread transfer of plants, animals, and diseases between the New World (the Americas) in the Western Hemisphere, and the Old World (Afro-Eurasia) in the Eastern Hemisphere, from the late 15th century on. It is named after the explorer Christopher Columbus and is related to the European colonization and global trade following his 1492 voyage. Some of the exchanges were deliberate while others were unintended.” (Wikipedia) Another aspect of this period is the natural advent of cultural clashes which we will touch upon about in The Pilgrims — The Native Peoples.

Il Costume Antico et Moderno, i.e. The Ancient and Modern Costume (1817–26).

(Image courtesy of Encyclopædia Britannica).

Observation: Maybe it is due to Hollywood movies, or perhaps it is just a natural way that the human mind works, but… it seems as if everyone, (with us included), tends to have a manner in which we project the consciousness of the present period back upon the times when our ancestors lived. They were not like those of us in the present day, because their eras were very much different from ours. To help understand their worldviews, we are going to outline three ways in which The Pilgrims were unlike people who are living today. (2)

Theirs Was A Pre-Scientific World

Our Pilgrim ancestors were living in a pre-scientific world in which religion was still the dominant player. That point-of-view might be a little hard for those of us in the modern world to understand. Before us, people didn’t have the perspective to comprehend things which we take for granted: stars and planets, germ-theory, equal opportunity, democratic rule, freedom of religion, etc.

New worlds were being discovered, but their world was still the Britain of their ancient forebears. What was ahead was a century of continued ongoing conflict in which royalty and the church were pitted against each other for control of the English people.

“The English Renaissance was a cultural and artistic movement in England from the early 16th century to the early 17th century. It is associated with the pan-European Renaissance that is usually regarded as beginning in Italy in the late 14th century. As in most of the rest of northern Europe, England saw little of these developments until more than a century later. Renaissance style and ideas, however, were slow to penetrate England, and the Elizabethan era in the second half of the 16th century is usually regarded as the height of the English Renaissance.

(Image courtesy of Meisterdrucke Fine Art Prints).

The English Renaissance is different from the Italian Renaissance in several ways. The dominant art forms of the English Renaissance were literature and music. Visual arts in the English Renaissance were much less significant than in the Italian Renaissance. The English period began far later than the Italian…” (Wikipedia)

To understand how much change was afoot in the world — here are just a few of the people who were alive during the century of 1530-1630 outside of England — artists, scientists, philosophers: Michelangelo, Copernicus, Galileo Galilei, René Descartes. Inside of England, it was a virtual hit parade of politicians, but also some explorers and writers: Henry VIII, Elizabeth I, Mary Queen of Scots, Sir Francis Drake, William Shakespeare, Walter Raleigh, Oliver Cromwell.

Our forebears lived during a time at the very beginning of scientific invention, even though much of this information took decades to develop and disperse across the world. The Enlightenment and the Age of Reason were yet to come. As an example, when our ancestors gazed with wonder upon the stars of the night sky, their conception of the world was very different from our understanding today… (3)

The Earth Was The Center Of Their Universe

We think about what their journey on the Mayflower must have been like — sailing under the vastness of the night sky, with just the cool light of the stars to guide them. Or perhaps standing on the shores of the new Plymouth, staring out at a universe, something they may have wondered about — but then, they barely knew how to think about it like we do. In their world, the Earth was the center of the universe. This is called the Copernican Heliocentric model and what this means is, “…the Sun [is positioned] at the center of the Universe, motionless, with Earth and the other planets orbiting around it in circular paths… at uniform speeds.” (Wikipedia)

This of course, changed in the decades that followed, but few of the Pilgrims likely knew this. Ironically, the telescope was invented in the Netherlands in 1608 while they were living in Leyden [Leiden]. Through subsequent refinements and improvements, the telescope became fundamental in helping Galileo Galilei develop his theories, published in the Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems (1632), which was a rejection of the Copernican Heliocentric model.

This “was met with opposition from within the Catholic Church and from some astronomers. The matter was investigated by the Roman Inquisition in 1615, which concluded that his opinions contradicted accepted Biblical interpretations. Galileo later defended his views in Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems (1632), which appeared to attack and ridicule Pope Urban VIII, thus alienating both the Pope and the Jesuits, who had both strongly supported Galileo up until this point. He was tried by the Inquisition, found ‘vehemently suspect of heresy’, and forced to recant. He spent the rest of his life under house arrest.” (Wikipedia) (4)

They Had No Concept of Germ Theory

We can thank our lucky stars* that we now live in a time when medicine has evolved beyond the ideas that were once widely believed in the time of these ancestors.

“In Tudor times, the understanding of medicine and the human body was based on the theory of the four bodily humours. This idea dates back to ancient Greece, where the body was seen more or less as a shell containing four different humours, or fluids: blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile. The humours affect your whole being, from your health and feelings, to your looks and actions. The key to good health (and being a good person) is to keep your humours in balance. However, everyone has a natural excess of one of the humours, which is what makes us all look unique and behave differently. Shakespeare even mentions them on his plays: how medicine formed part of people’s lives and thoughts.” (Tudorworld.com)

by Leonhart Thurneisser zum Thurn, circa 1574.

As shown in the images above, the belief then was that humours were tied to the different seasons, and hence, their corresponding astrological signs. [Observation: *Lucky Stars — The use of this funny expression seems to imply that our belief in Astrology is still ok, no?]

“Humorism began to fall out of favor in the 17th century and it was definitively disproved in the 1850s with the advent of germ theory, which was able to show that many diseases previously thought to be humoral were in fact caused by microbes.” (Wikipedia)

“The English of that era really couldn’t bathe even if they wanted to, notes V. W. Greene, a professor of epidemiology at the Ben Gurion Medical School in Beersheva, Israel. “There was no running water, streams were cold and polluted, heating fuel was expensive, and soap was hard to get or heavily taxed. There just weren’t facilities for personal hygiene. Cleanliness wasn’t a part of the folk culture.” (Lies My Teacher Told Me – LMTTM; See footnotes, V. W. Greene)

“Queen Isabella boasted that she took only two baths in her life,

excerpts from an article written by Jay Stuller

at birth and before her marriage.”

“Colonial America’s leaders deemed bathing impure, since

it promoted nudity, which could only lead to promiscuity.”

titled “Cleanliness has only recently become a virtue”

Smithsonian Magazine, February 1991

It’s no wonders perfumes were highly coveted possessions.

It took another 230 to 300 years for the understanding of germ theory to take hold in the popular consciousness. As explained by Encyclopædia Britannica, “Developed, verified, and popularized between 1850 and 1920, germ theory holds that certain diseases are caused by the invasion of the body by microorganisms. Research by Louis Pasteur, [and others] contributed to public acceptance of the once-baffling theory, proving that processes such as fermentation and putrefaction, as well as diseases such as cholera and tuberculosis, were caused by germs.

Before germ theory was popularly understood, the methods taken to avoid illness and infection were based on guesses rather than facts. After germ theory’s development and popularization, effective sanitation practices resulted in cleaner homes, hospitals, and public spaces— as well as longer life spans for the people who had never before known how to avoid getting sick.” (Encyclopædia Britannica) (5)

There Was No Concept of An Inherent Bill of Rights

Despite what many people think, the Mayflower Compact was not a democratic declaration of rights. (This is covered in the chapter, The Pilgrims — A Mayflower Voyage). What we want to convey here is that the day-to-day personal rights and freedoms which now exist and which many take for granted, didn’t exist at that time.

Much later than 1620, when the young United States adopted the Bill of Rights as the first 10 amendments to the Constitution in 1791, they began with the “First Amendment and Religion. The First Amendment has two provisions concerning religion: the Establishment Clause and the Free Exercise Clause. The Establishment clause prohibits the government ‘establishing’ a religion. The precise definition of ‘establishment’ is unclear. Historically, it meant prohibiting state-sponsored churches, such as the Church of England.” (See footnotes, United States Courts)

For The Pilgrims and all of their forebears, they lived their entire lives under the rule of a Monarch. We understand from their history that The Pilgrims desired to have religious freedom to worship as they saw appropriate. This was certainly a minority opinion when you live under a King who took a strong interest in religious matters. That said, British law had been taking an ever so slow drift toward some personal rights, but the freedom of religious choice and worship was not among them.

However, in the long history of English common law, there were some milestones which came to eventually influence the future American Bill of Rights. These same developments were likely heard as the background music of the Pilgrim experiences in both England and Holland. As such, they may have been thinking about, or debating them occasionally, especially when new emigrants from England entered their community.

Three Key Documents From English Law, and One From Colonial Law

The Teaching American History website, helps us understand how these rights came to be — In the England of 1215, “the most important contribution of the Magna Carta is the claim that there is a fundamental set of principles, which even the King must respect. Above all else, Magna Carta makes the case that the people have a ‘right’ to expect ‘reasonable’ conduct by the monarch. These rights are to be secured by the principle of representation.” (See footnotes, Teaching American History – TAH )

It is interesting to observe that the Magna Carta is about equally distant in time from The Pilgrims, as they are from us today.

The Pilgrims were English citizens (along with some Walloon and Dutch citizens) who, even though they were in the New World, they were required to abide by British law. Soon after they left on the Mayflower, “The 1628 Petition of Right is the second of the three British documents that provided a strong common law component to the development of the American Bill of Rights. In the thirteenth century, the nobles petitioned the King to abandon his arbitrary and tyrannical policies; four centuries later, [and most importantly] it was the commoners who petitioned the King to adhere to the principles of reasonable government bequeathed by the English tradition.”

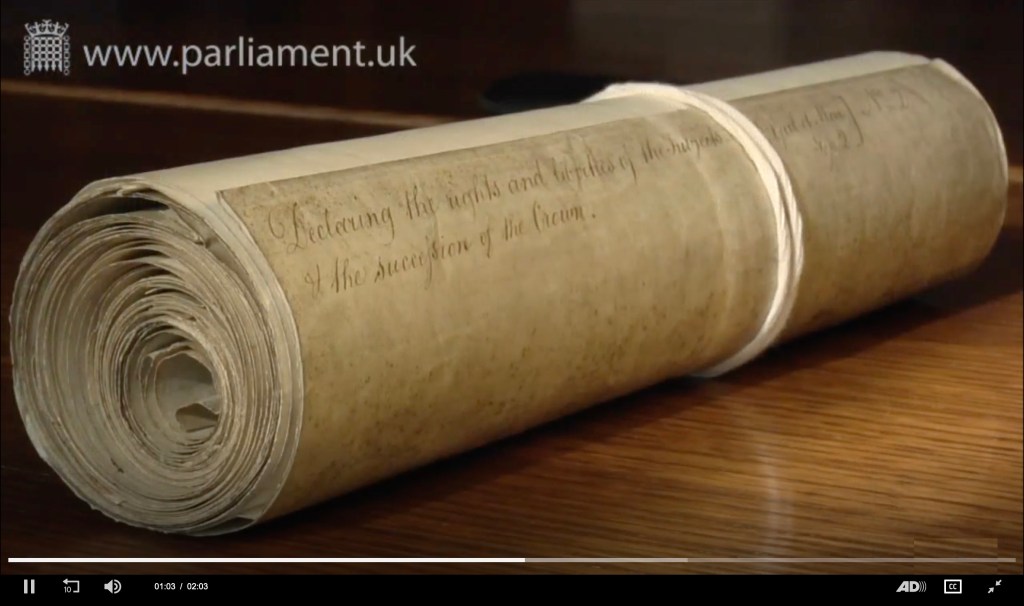

“The third British contribution to the development of the American Bill of Rights is the 1689 English Bill of Rights… several ancient rights of Englishmen are reaffirmed: the right to petition government for the redress of grievances, the expectation that governmental policy shall confirm to the rule of law… the freedom of speech and debate and that there were to be frequently held elections. Not included, however, in the declaration of rights [is] that Englishmen have are the right to the free exercise of religion and the right to choose their form of government.” (See footnotes, TAH)

Click the link below to see a two minute video of the actual 1689 document: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Bill-of-Rights-British-history/images-videos#/media/1/503538/210012

Outcome: 7 of 26 rights in the U.S. Bill of Rights can be traced to the English Petition of Rights, and 7 more to the English Bill of Rights. However, with some duplication, these all net out to be 10 rights. (7)

From Colonial Law — The Massachusetts Body of Liberties of 1641

“The Massachusetts Body of Liberties, adopted in December 1641, was the first attempt in Massachusetts to restrain the power of the elected representatives by an appeal to a document that lists the rights, and duties, of the people. The document, drafted and debated over several years, combines the American covenanting tradition [to make an agreement; a covenant] with an appeal to the common law tradition.

(Image courtesy of Wikipedia).

Even more importantly, there is a distinctively qualitative difference in the emerging Colonial American version of rights. Unique is the emergence of the individual right of religious worship, the political rights of press and assembly, and what became the Sixth Amendment in the U.S. Bill of Rights dealing with accusation, confrontation, and counsel. These are home grown.” (See footnotes, TAH)

Outcome: There is a strong relationship between the U.S. Bill of Rights and the Colonial past. 18 of 26 rights in the U.S. Bill of Rights, or 70%, can be traced directly to the Colonial tradition. And 15 of 26 rights, or 60%, come from one source alone: the Massachusetts Body of Liberties of 1641.

The currents for these reforms began with, and continued to thrive with, our ancestors when they came to this part of the world. This process still continues to evolve, even to this very day. (8)

Following are the footnotes for the Primary Source Materials,

Notes, and Observations

Atlantic Overture

(1) — two records

Saints and Strangers: Being the Lives of the Pilgrim Fathers & Their Families

by George F. Willison

https://archive.org/details/dli.ernet.13804/page/509/mode/2up

Book page: 509, Digital page: 509/513

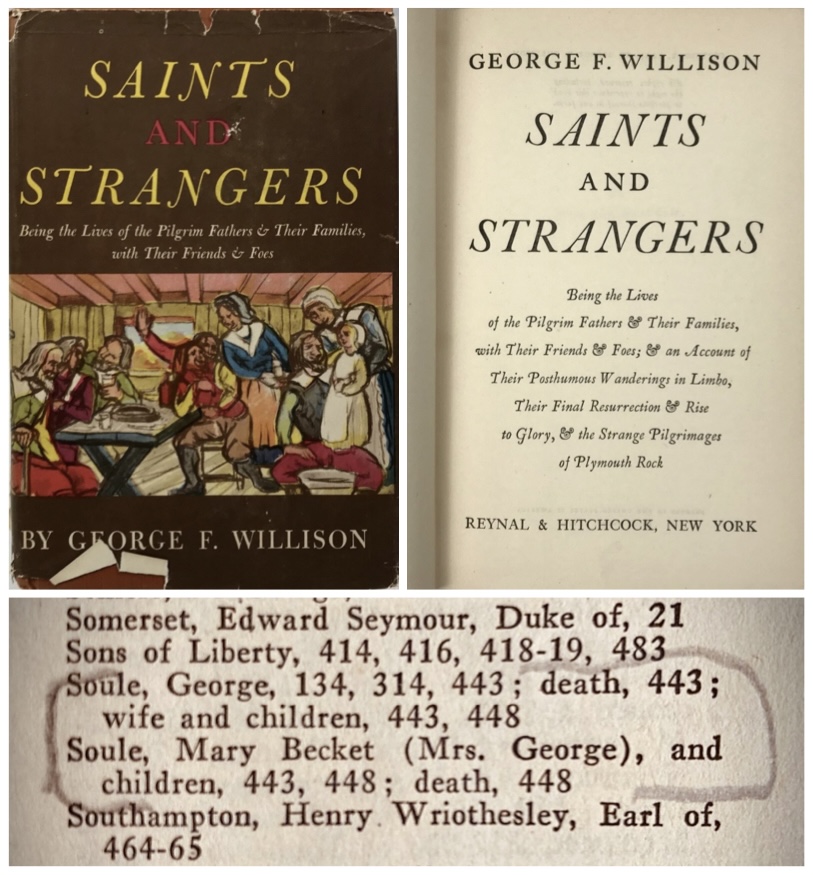

Isolation: The Mayflower becalmed on a moonlit night

by Montague Dawson, (British, 1890-1973)

https://www.mutualart.com/Artwork/Isolation–The-Mayflower-becalmed-on-a-m/FD8D6C1A6976C620

Note: For the image of the Mayflower painting.

The Columbian Exchange

(2) — two records

Columbian Exchange

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Columbian_exchange

Note: For the text.

Encyclopædia Britannica

Columbian Exchange

Columbus Arriving in the New World

by Unknown Artist

https://cdn.britannica.com/08/142308-050-B404CF9D/Christoper-Columbus-New-World-worlds-Western-Hemisphere-1492.jpg

Note: Christopher Columbus Arriving in The New World, illustration in

Il Costume Antico et Moderno, i.e. The Ancient and Modern Costume (1817–26).

Theirs Was A Pre-Scientific World

(3) — two records

English Renaissance

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/English_Renaissance

Note: For the text.

Shakespeare and his Friends at the Mermaid Tavern

by John Faed, circa 1850

https://www.meisterdrucke.ie/fine-art-prints/John-Faed/281952/Shakespeare-and-His-Friends-at-the-Mermaid-Tavern.html

Note: For the image of the painting.

The Earth Was The Center Of Their Universe

(4) — eight records

The Astronomer

by Johannes Vermeer

File:Johannes Vermeer – The Astronomer – 1668.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Johannes_Vermeer_-_The_Astronomer_-_1668.jpg

Note: For the image of the Vermeer painting.

Copernican Heliocentrism

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Copernican_heliocentrism

Note: This model positioned the Sun at the center of the Universe, motionless, with Earth and the other planets orbiting around it in circular paths, modified by epicycles, and at uniform speeds..

History of The Telescope

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_telescope

Note: “The history of the telescope can be traced to before the invention of the earliest known telescope, which appeared in 1608 in the Netherlands“.

Galileo Galilei at His Trial by the Inquisition in Rome in 1633, i.e. Galileo pushes away the Bible.

Courtesy of The Wellcome Collection via Wikimedia Commons

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Galileo_Galilei_at_his_trial_Wellcome_V0018717.jpg#/media/File:Galileo_Galilei;_Galileo_Galilei_at_his_trial_at_the_Inquisi_Wellcome_V0018716.jpg

Note: For the image of the trial of Galileo Galilei.

Galileo Galilei

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Galileo_Galilei

Note: For the text.

File:Galileos Dialogue Title Page.png

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Galileos_Dialogue_Title_Page.png

Note: “Frontispiece (by Stefan Della Bella) and title page of Galileo Galilei’s Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, published by Giovanni Battista Landini in 1632 in Florence.”

File:Emblemata 1624.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Emblemata_1624.jpg

Note: “Early depiction of a ‘Dutch telescope’ from the “Emblemata of zinne-werck” (Middelburg, 1624) of the poet and statesman Johan de Brune (1588-1658).”

Science — 50 Photos Taken on The Moon

by Jessica Learish

https://www.cbsnews.com/pictures/apollo-11-50th-anniversary-50-photos-taken-on-the-moon/

Note: For the July 1969 image, “This photo was taken from the Apollo 11 Columbia command module, shortly before the lunar module was dispatched to the surface.”

They Had No Concept of Germ Theory

(5) — eight records

What Were the Four Humours?

https://tudorworld.com/wp-content/uploads/The-Four-Humours-Information.pdf

Note: For the text.

Humoralism and The Seasons

by Elisabeth Brander

https://becker.wustl.edu/news/humoralism-and-the-seasons/

Note: For the text.

Humorism

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Humorism

Note: For the text.

Book illustration in “Quinta Essentia”

by Leonhart Thurneisser zum Thurn, circa 1574

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Quinta_Essentia_(Thurneisse)_illustration_Alchemic_approach_to_four_humors_in_relation_to_the_four_elements_and_zodiacal_signs.jpg

Note: Woodcut print of the Alchemic approach to four humors in relation to the four elements and zodiacal signs.

V. W. Greene quoted in:

English-Word Information, Ablutions or Bathing, Historical Perspectives

https://wordinfo.info/unit/2701

Notes: “Colonial America’s leaders deemed bathing impure, since it promoted nudity, which could only lead to promiscuity.”

and

“The English of that era really couldn’t bathe even if they wanted to, notes V. W. Greene, a professor of epidemiology at the Ben Gurion Medical School in Beersheva, Israel. “There was no running water, streams were cold and polluted, heating fuel was expensive, and soap was hard to get or heavily taxed. There just weren’t facilities for personal hygiene. Cleanliness wasn’t a part of the folk culture.”

[LMTTM]

Lies My Teacher Told Me

by James W. Loewen

https://www.google.pt/books/edition/Lies_My_Teacher_Told_Me/5m23RrMeLt4C?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA1&printsec=frontcover

Book pages: 70-92

Note: Cited in LMTTM, by author Jay Stuller, — “Cleanliness has only recently become a virtue… Queen Isabella boasted that she took only two baths in her life, at birth and before her marriage.”

Cited in this article by author Jay Stuller —

Smithsonian Magazine

Cleanliness Has Only Recently Become a Virtue

by Jay Stuller

February 1991, pages 126-135

File:Cholera art.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cholera_art.jpg

Note: A representation by Robert Seymour of the cholera epidemic of the 19th century depicts the spread of the disease in the form of deadly air via miasma.

Encyclopædia Britannica

What Was Life Like Before We Knew About Germs?

https://www.britannica.com/story/what-was-life-like-before-we-knew-about-germs

Note: For the text.

There Was No Concept of An Inherent Bill of Rights

(6) — two records

United States Courts

First Amendment and Religion

https://www.uscourts.gov/about-federal-courts/educational-resources/about-educational-outreach/activity-resources/first-amendment-and-religion

Note: For the text.

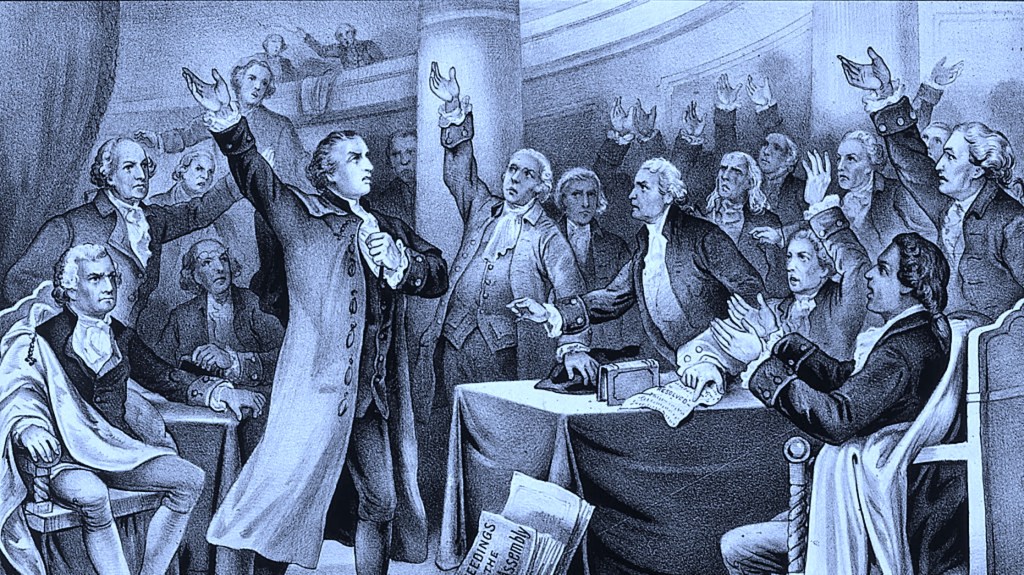

Library of Congress

“Give me liberty, or give me death!” Patrick Henry delivering his great speech on the rights of the colonies, before the Virginia Assembly, convened at Richmond, March 23rd 1775, concluding with the above sentiment, which became the war cry of the revolution.

https://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/pga.08961/

Note: For the artwork.

Three Key Documents From English Law, and One From Colonial Law

(7) — two records

(TAH)

The Origin of the Bill of Rights

by Natalie Bolton

https://teachingamericanhistory.org/resource/lessonplans/the-origin-of-the-bill-of-rights/

Note: For the text.

The National Archives

Magna Carta

https://www.archives.gov/exhibits/featured-documents/magna-carta

Note: For the image of the Magna Carta document.

From Colonial Law — The Massachusetts Body of Liberties of 1641

(8) — three records

(TAH)

The Origin of the Bill of Rights

by Natalie Bolton

https://teachingamericanhistory.org/resource/lessonplans/the-origin-of-the-bill-of-rights/

Note: For the text.

Encyclopædia Britannica

Bill of Rights: Media

See the Bill of Rights 1689 and the Draft Declaration of Rights (1689)

kept in the United Kingdom Parliamentary Archives Search Room

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Bill-of-Rights-British-history/images-videos#/media/1/503538/210012

Note: For the video link.

Pilgrims Going To Church

by George Henry Boughton, circa 1867

File:George-Henry-Boughton-Pilgrims-Going-To-Church.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:George-Henry-Boughton-Pilgrims-Going-To-Church.jpg

Note: For the image of a Pilgrim church gathering.