This is Chapter Six of seven. Long before our ancestors had arrived in the New Plymouth, the native peoples who already lived there had more than a century of experience with the Europeans.

In the first chapter, The Pilgrims — Saints & Strangers, we briefly learned about some of the historical consequences of the Columbian Exchange. We were then choosing to apply a light touch to that history, but here in this chapter, we need to delve more deeply.

circa 1597. (Image courtesy of The Newberry Library).

The Americas and The Great Dying

“The first manifestation of the Columbian Exchange may have been the spread of syphilis from the native people of the Caribbean Sea to Europe. The history of syphilis has been well-studied, but the origin of the disease remains a subject of debate.

There are two primary hypotheses: one proposes that syphilis was carried to Europe from the Americas by the crew of Christopher Columbus in the early 1490s, while the other proposes that syphilis previously existed in Europe but went unrecognized. The first written descriptions of syphilis in the Old World came in 1493. The first large outbreak of syphilis in Europe occurred in 1494–1495 among the army of Charles VIII during its invasion of Naples. Many of the crew members who had served with Columbus had joined this army. After the victory, Charles’s largely mercenary army returned to their respective homes, spreading “the Great Pox” across Europe, which killed up to five million people.” (Wikipedia)

Data gathered was from Wikipedia, and The National Library of Medicine, United Kingdom.

(See footnotes).

The Columbian Exchange of diseases towards the New World was far deadlier. The peoples of the Americas had previously had no exposure to Old World diseases and little or no immunity to them. An epidemic of swine influenza beginning in 1493 killed many of the Taino people inhabiting Caribbean islands. The pre-contact population of the island of Hispaniola was probably at least 500,000, but by 1526, fewer than 500 were still alive. Spanish exploitation was part of the cause of the near-extinction of the native people. (Wikipedia)

In 1518, smallpox was first recorded in the Americas and became the deadliest imported Old World disease. Forty percent of the 200,000 people living in the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan, later Mexico City, are estimated to have died of smallpox in 1520 during the war of the Aztecs with conquistador Hernán Cortés. Epidemics, possibly of smallpox, spread from Central America, devastated the population of the Inca Empire a few years before the arrival of the Spanish. The ravages of Old World diseases and Spanish exploitation reduced the Mexican population from an estimated 20 million to barely more than a million in the 16th century. (Wikipedia)

“There is disagreement regarding the number of Native Peoples before the first Europeans set foot in North America, but approximately five to eighteen million is currently the best estimate, and a much larger population of over 100 million including throughout the Americas and West Indies is probable. The arrival of Europeans… resulted in a catastrophic ‘demographic collapse’ of up to 95% of the indigenous population. By the beginning of the 20th Century, the number of Native Americans in this country had been reduced to about 237,000 people through disease, war, and relocation.” (See footnotes, Ipswich) (1)

of the Indian Wars, From the Landing of Our Pilgrim Fathers, 1620. It was published in 1854,

by Henry Trumbull, Susannah Willard, and Zadock Steele. (See footnotes).

Closer to Home in New England

“The Wampanoag Tribe, also known as the People of the First Light, has inhabited present-day Massachusetts and Eastern Rhode Island for more than 12,000 years. In the 1600s, there were as many as 40,000 people in the 67 villages that made up the Wampanoag People, who firstly lived as a nomadic hunting and gathering culture. By about 1000 AD, archaeologists have found the first signs of agriculture, in particular the corn crop, which became an important staple, as did beans and squash.” (Mayflower 400)

Dr. Ian Saxine of Bridgewater State University, when interviewed near the time of the Mayflower’s 400th anniversary stated, “There is evidence that the inhabitants of the Outer Cape had interacted with European sailors from Portugal, England and France for at least 200 years. They traded, and at times, fought.” (GBH News) This area is shown on the right portion of the map below.

Map of Wampanoag Country in the 1600s.

Wampanoag territory in the 1600s was made up of about 67 villages, and this map shows some of them. The larger print shows the Wampanoag name, and the smaller print gives the modern name. (Map courtesy of Plimoth Patuxet Museums).

“Entire villages were lost and only a fraction of the Wampanoag Nation survived. This meant they were not only threatened by the effects of colonisation but vulnerable to rival tribes and struggled to fend off the neighbouring Narragansett, who had been less affected by this plague.

In the winter of 1616-17 an expedition dispatched by Sir Ferdinando Gorges found a region devastated by war and disease, the remaining people so “sore afflicted with the plague, for that the country was in a manner left void of inhabitants”. Two years later another Englishman found “ancient plantations” now completely empty with few inhabitants – and those that had survived were suffering.

In the years before the Mayflower arrived, the effects of colonization had already taken root.” (Mayflower 400)

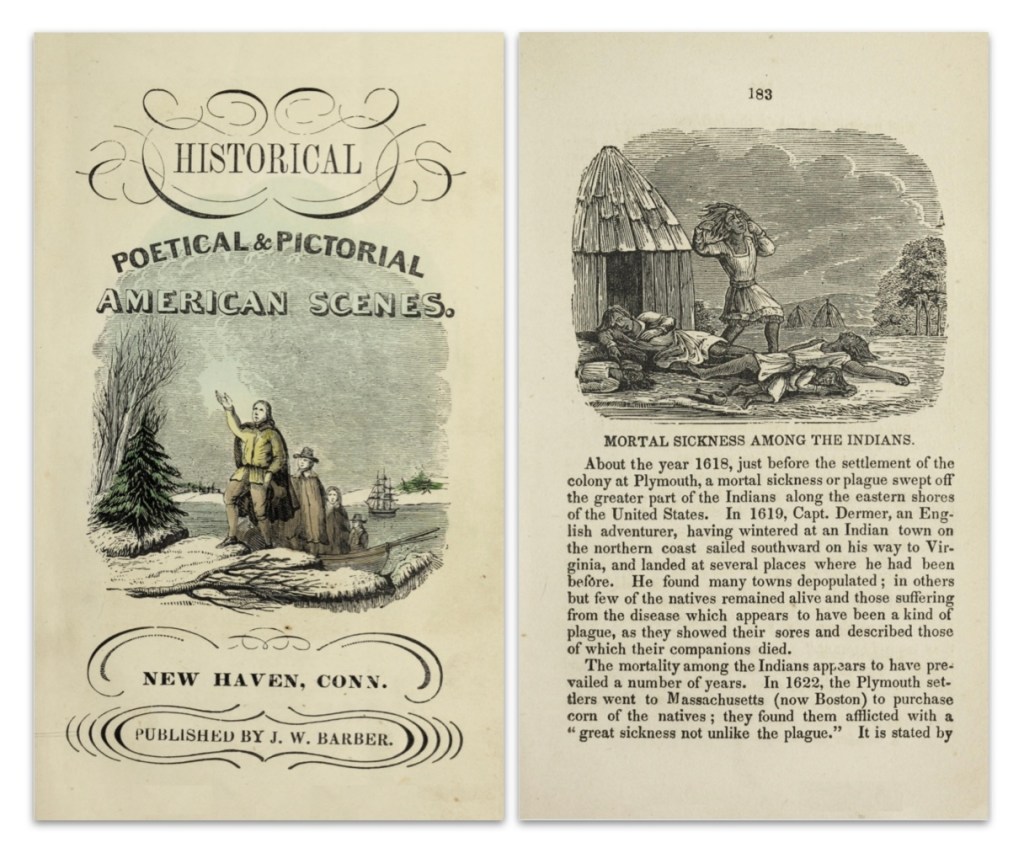

Principally Moral and Religious: Being a Selection of Interesting Incidents in American History

to Which is Added a Historical Sketch of Each of the United States,

by John W. Barber and Elizabeth G. Barber, 1850. (Images courtesy of the Hathi Trust).

When the sickness came, the reduction of the population may have been incremental, episodic, and continuous, but in the end, it was relentless.

For the tribe with whom our family (mostly) interacted with, “the extraordinary impact of the Great Dying meant the Wampanoag had to reorganize its structure and the Sachems [the North American Indian chiefs] had to join together and build new unions.” (Mayflower 400)

“When we look back on the Aborigines, as the sole proprietors

Joseph Felt writing in his 1834 book,

of our soil, on the places which once knew them,

but are now to know them no more forever,

feelings of sympathy and sadness come over our souls.

In the light of history,

a tribe of men immortal as ourselves… have irrevocably

disappeared from the scenes and concerns of earth.

“History of Ipswich, Essex and Hamilton”

If you recall when we wrote in The Pilgrims — Saints & Strangers, we drew attention to the fact that people then had no concept of germ theory. The very healthy nature of the Native Peoples “proved their undoing, for they had built up no resistance, genetically or through childhood diseases, to the microbes that Europeans and Africans would bring to them. They did not cause the plague and were as baffled as to its origin as the stricken Indian villagers.

These epidemics probably constituted the most important geopolitical event of the early seventeenth century. Their net result was that the English, for their first fifty years in New England, would face no real Indian challenge.” (Lies My Teacher Told Me – LMTTM)

Nature loves to exploit a new environmental niche, and viruses that complicate our lives are unintentionally skilled at exploiting new opportunities. We all know this, with the most recent example being the global SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19).

It was into this world of empty landscapes that the Plimoth Plantation began. (2)

First Encounters With The Pilgrims

From the standpoint of the Native People, when the Pilgrims first arrived, their memories of some of their own having been taken prisoner and sold into slavery, led some to act aggressively. “The First Encounter… was not so much an attack on the English settlers as the Wampanoags defending themselves and their culture. Pilgrim records say the Nauset [a neighboring tribe of the Wampanoags] attacked once the Pilgrims had pulled their small boat ashore after spending the day exploring along the coast and were camped out near the beach. Although the Pilgrims and Nauset engaged in a brief firefight, there is no record of any deaths or injuries.

Saxine [of Bridgewater State University] said both sides felt they had won what was the first violent engagement between the Native Americans and the European settlers who would later colonize Plymouth. The Mayflower party felt that they had won because the Nauset fighters pulled back after this firefight,” Saxine said. “The Nauset probably felt they had won because the English people sailed away and left them alone.” (GBH News) (3)

November 1620 (painting), by W.J. Aylward. (Image courtesy of Historynet.com)

These People Were Different.

“The story of the Pilgrims… has been told primarily from the English colonists’ point of view. How the Native Americans felt about the colonists’ arrival in the New World has been mostly absent from the story.” (GBH News)

“Four hundred years ago, this newly organised People [after the Great Dying] watched as yet another ship arrived from the east. These people were different. The Wampanoag watched as women and children walked from the ship, using the waters to wash themselves. Never before had they seen Europeans engage in such an act. They watched cautiously as the men of this new ship explored their lands, finding what remained of Patuxet and building homes. They watched them take corn and beans, probably winter provisions, stored for the harsh conditions that were to come. The Wampanoag People did not react.

Given the horrific nature of the past years, the Wampanoag People were understandably wary of this new group. Months would pass before contact. But in this time, they would have recognised the opportunity for a new alliance to help them survive.” (Mayflower 400) (3)

Discovering Indian Corn… and Graves

In the book, 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus, author Charles C. Mann, states to National Geographic —

“When the pilgrims arrived in Cape Cod, they were incredibly unprepared. “They were under the persistent belief that because New England is south of the Netherlands and southern England, it would therefore be warmer,” says Mann. “Then they showed up six weeks before winter [actually less than six weeks] with practically no food.” In a desperate state, the pilgrims robbed corn from Native Americans graves and storehouses soon after they arrived; but because of their overall lack of preparation, half of them still died within their first year.

If the pilgrims had arrived in Cape Cod three years earlier, they might not have found those abandoned graves and storehouses… in fact, they might not have had space to land. Europeans who sailed to New England in the early to mid-1610s found flourishing communities along the coast, and little room for themselves to settle. But by 1620, when the Mayflower arrived, the area looked abandoned.

“Having their guns and hearing nobody, they entered the houses and found the people were gone. The sailors took some things but didn’t dare stay. . . . We had meant to have left some beads and other things in the houses as a sign of peace and to show we meant to trade with them. But we didn’t do it because we left in such haste. But as soon as we can meet with the Indians, we will pay them well for what we took.”

“We marched to the place we called Cornhill, where we had found the corn before. At another place we had seen before, we dug and found some more corn, two or three baskets full, and a bag of beans… In all we had about ten bushels, which will be enough for seed. It was with God’s help that we found this corn, for how else could we have done it, without meeting some Indians who might trouble us.”

“A couple of years before, there’d been an epidemic that wiped out most of the coastal population of New England, and Plymouth was on top of a village that had been deserted by disease,” says Mann. “The pilgrims didn’t know it, but they were moving into a cemetery,” he adds.

“The next morning, we found a place like a grave. We decided to dig it up. We found first a mat, and under that a fine bow. . . . We also found bowls, trays, dishes, and things like that. We took several of the prettiest things to carry away with us, and covered the body up again.”

“The newcomers did eventually pay the Wampanoags for the corn they had dug up and taken. Plymouth, unlike many other colonies, usually paid Indians for the land it took. In some instances Europeans settled in Indian towns because Natives had invited them, as protection against another tribe, or a nearby competing European power.” (National Geographic, and LMTTM)

“…just as the Pilgrims don’t represent all English colonists, the Wampanoags, who feasted with them, don’t represent all Native Americans. The Pilgrims’ relations with the Narragansetts, or the Pequots, were completely different.” (National Endowment For The Humanities – NEFTH) (5)

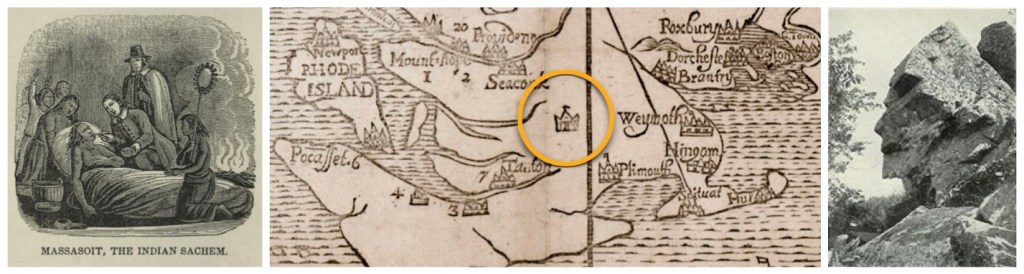

The Wampanoag Confederacy of Massasoit Sachem

The history that has come down to us today, records four individuals who made important differences in the lives of the Pilgrims, and helped them to succeed with their new colony endeavors.

Massasoit was the Sachem, or leader of the Wampanoag confederacy. Massasoit Sachem means the Great Sachem. Although Massasoit was only his title, English colonists mistook it as his name and it stuck. Massasoit needed the Pilgrims just as much as they needed him. [His] people had been seriously weakened by a series of epidemics and were vulnerable to attacks by the Narragansetts, and he formed an alliance with the colonists at Plymouth Colony for defense against them. It was through his assistance that the Plymouth Colony avoided starvation during the early years.

At the time of the Pilgrims’ arrival in Plymouth, the realm of the Wampanoag, also known as the Pokanokets, included parts of Rhode Island and much of southeastern Massachusetts. Massasoit lived in Sowams, a village at Pokanoket in Warren, Rhode Island. He held the allegiance of lesser Pokanoket Sachems [chiefs].

Massasoit forged critical political and personal ties with colonial leaders William Bradford, Edward Winslow, Stephen Hopkins, John Carver, and Myles Standish, ties which grew out of a peace treaty negotiated on March 22, 1621. The alliance ensured that the Pokanokets remained neutral during the Pequot War in 1636. According to English sources, Massasoit prevented the failure of Plymouth Colony and the starvation that the Pilgrims faced during its earliest years.

Massasoit was humane and honest, kept his word, and endeavored to imbue his people with a love for peace. He kept the Pilgrims advised of any warlike designs toward them by other tribes. It is unclear when Massasoit died. Some accounts claim that it was as early as 1660; others contend that he died as late as 1662. He was anywhere from 80 to 90 at the time.” (Wikipedia)

“In Winslow’s second published book, ‘Good Newes from New England (1624),’ he recounted at length nursing the Wampanoag leader Massasoit as he lay dying, even to the point of spoon-feeding him chicken broth.” (See footnotes, The Conversation) (6)

Samoset, the Abenaki Native American

This is how we first learn of Samoset, “Yet, in March, a lone Indian warrior named Samoset appeared and greeted the settlers, improbably, in English. Soon, the Pilgrims formed an alliance with the Wampanoags and their chief, Massasoit. Only a few years before, the tribe had lost 50 to 90 percent of its population to an epidemic borne by European coastal fisherman. Devastated by death, both groups were vulnerable to attack or domination by Indian tribes. They needed each other.” (NEFTH)

He “was the Abenaki Native American who first approached the English settlers of Plymouth Colony in friendship, introducing them to [the] natives Squanto and Massasoit who would help save and sustain the colony.

He was a Sagamore (Chief) of the Eastern Abenaki, who was either visiting Massasoit or had been taken prisoner by him sometime before the Mayflower landed off the coast of modern-day Massachusetts in November 1620. Massasoit chose him to make first contact with the pilgrims in March of 1621, and he has been recognized since as instrumental in bringing the Native Americans of the Wampanoag Confederacy and English colonists of Plymouth together in a compact which would remain unbroken for the next 50 years.”

All that is known of Samoset comes from these works except for a passing mention by the explorer Captain Christopher Levett who met Samoset in 1624 at present-day Portland, Maine, and considered it an honor based on Samoset’s role in helping to sustain Plymouth Colony in 1621. Samoset was highly regarded by other English and European colonists following his appearance in Mourt’s Relation, published in 1622. (World History Encyclopedia) (7)

by Charles de Wolf Brownell, circa 1864. (See footnotes).

Tisquantum, Who is Also Known as Squanto

“A Native American called Tisquantum was born in 1580. He became known as Squanto and little is known of his early life. Some believe he was captured as a young man on the coast of what is now Maine by Captain George Weymouth in 1605. Weymouth was an Englishmen commissioned to explore the American coastline and thought his financial backers might like to see Native American people.

“What do most books leave out about Squanto? First, how he learned English. Squanto spent nine years [in England, with three years being in the employ of Ferdinando Gorges]. At length, Gorges helped Squanto arrange passage back to Massachusetts. Some historians doubt that Squanto was among the five Indians stolen in 1605. All sources agree, however, that in 1614 an English slave raider, Thomas Hunt, lured 24 Native Americans on board his ship under the premise of trade. Their number included Tisquantum. Hunt locked them up below deck, sailed for Spain and sold these people into the European slavery in Málaga, Spain. Squanto escaped from slavery, escaped from Spain, and made his way back to England.

(Image courtesy of Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg).

After trying to get home via Newfoundland, in 1619 he talked Thomas Dermer into taking him along on his next trip to Cape Cod as an interpreter. He searched for his homeland but tragically, he arrived as the Great Dying reached its horrific climax. His tribe had all been wiped out two years before.. His home village, Patuxet, was lost. — No wonder Squanto threw in his lot with the Pilgrims.” (LMTTM and Mayflower 400)

Excerpted from Lies My Teacher Told Me, by James W. Loewen, page 88.

“As translator, ambassador, and technical advisor, Squanto was essential to the survival of Plymouth in its first two years. Like other Europeans in America, the Pilgrims had no idea what to eat or how to raise or find food until American Indians showed them. [Massasoit was, as the Great Sachem of the Wampanoag Confederacy, the one who sent Tisquantum (Squanto) to live among the Pilgrim colonists.]

William Bradford called Squanto “a special instrument sent of God for their good beyond their expectation. He directed them how to set their corn, where to take fish, and to procure other commodities, and was also their pilot to bring them to unknown places for their profit.” Squanto was not the Pilgrims’ only aide: in the summer of 1621 Massasoit sent another Indian, Hobomok, to live among the Pilgrims for several years as guide and ambassador.” (LMTTM)

Importantly, we learned that he “… facilitated understandings between the colony and its native neighbors and established trade relations with a number of villages.” (Wikipedia)

after an Illustration by C. W. Jefferys, 1926. (See footnotes).

“With spring, under the careful guidance of a Wampanoag friend, Tisquantum, the settlers planted corn, squash, and beans, with herring for fertilizer. They began building more houses, fishing for cod and bass, and trading with the Native Americans. By October, they had erected seven crude houses and four common buildings.” (NEFTH) (8)

Hobomok, A ‘Pneise’ of the Pokanoket

Almost nothing is known about Hobomok before he began living with the English settlers who arrived aboard the Mayflower. His name was variously spelled in 17th century documents and today is generally simplified as Hobomok, or Hobbamock. He was known as a Pneise, which means he was an elite warrior of the Algonquin people of Eastern Massachusetts. Also, he was a member of the Pokanoket tribe… whom Sachem Massasoit had authority over. William Bradford described him as “a proper lustie man, and a man of accounte for his vallour and parts amongst thed Indeans.”

“Hobomak is known to us primarily for his rivalry with Squanto, who lived with the settlers before him. He was greatly trusted by Myles Standish, the colony’s military commander, and he joined with Standish in a military raid against the Massachuset” [a neighboring tribe].

(Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, see footnotes).

Both Bradford and Winslow first record Hobomok’s actions in connection with a crisis in which Squanto was thought to have been kidnapped and possibly murdered. Long story short is that there were ongoing rival factions for control among the various Native nations, and therefore there was an attempt to have Massasoit driven “from his country.” Hobomak aided Miles Standish “to raid Nemasket at night to round up Corbitant and any accomplices.” This was a messy confrontation, but Squanto was released, and Massasoit remained as Sachem.

However, “The affair left the colony feeling exposed. They decided to protect the settlement by taking down tall trees, dragging them from the forest and sinking them in deep holes closely bound to prevent arrows from passing through. [This was the building of a stockade.] Moreover, Standish divided the men into four squadrons and drilled them on how to respond to an emergency, including instructions on how to remain armed and alert to a native attack even during a fire in the town.” (Adapted from Wikipedia)

“Hobomok helped Plymouth set-up fur trading posts at the mouth of the Penobscot and Kennebec rivers in Maine; in Aputucxet, Massachusetts, and in Windsor, Connecticut.” If you recall, the underwriters in London who had financed the voyage of the Mayflower still need to be reimbursed by the Pilgrims. The income generated by the sale and shipment of these fur skins back to the Europeans, helped to alleviate those debts. (LMTTM) (9)

Very Faithful in Their Covenant of Peace

When have written previously that it appeared that the demeanor of the Pilgrims had shifted during their years in Leyden, Holland. Perhaps after all of their harrowing experiences since they left there, some of them were becoming less strident in their views? We observed that instead of viewing the Native Peoples in America as Others — as they themselves had been treated in England — an appreciation and tolerance toward those who are different from them, had begun to take hold.

“At the same time, Pilgrims did not actively seek the conversion of Native Americans. According to scholars like [Nathaniel] Philbrick, English author Rebecca Fraser and [Mark] Peterson, the Pilgrims appreciated and respected the intellect and common humanity of Native Americans.

An early example of Pilgrim respect for the humanity of Native Americans came from the pen of Edward Winslow. Winslow was one of the chief Pilgrim founders of Plymouth. In 1622, just two years after the Pilgrims’ arrival, he published in the mother country the first book about life in New England, “Mourt’s Relation.”

While opining that Native Americans “are a people without any religion or knowledge of God,” he nevertheless praised them for being “very trusty, quick of apprehension, ripe witted, just.” Winslow added that “we have found the Indians very faithful in their covenant of peace with us; very loving. … we often go to them, and they come to us; some of us have been fifty miles by land in the country with them.” (See footnotes, The Conversation) (10)

Following are the footnotes for the Primary Source Materials,

Notes, and Observations

The Americas and The Great Dying

(1) — eight records

The Newberry Library

(The English Exporer) Bartholomew Gosnold trading with

Wampanoag Indians at Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts

by Theodor de Bay, circa 1597

https://collections.carli.illinois.edu/digital/collection/nby_eeayer/id/3563

Note: For the image.

Post-Columbian Transfer of Diseases chart, sources —

Columbian Exchange

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Columbian_exchange

Note: For the text and the image of, Sixteenth-century Aztec drawings

of victims of smallpox, from the Florentine Codex.

and

New Hypothesis for Cause of Epidemic among Native Americans,

New England, 1616–1619

by John S. Marr and John T. Cathey

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2957993/

Note: For the data, “…leptospirosis complicated by Weil syndrome, a rare but severe bacterial infection, spread by non-native black rats that arrived on the settlers’ ships.”

and

Smithsonian Magazine

Alfred W. Crosby on the Columbian Exchange

by Megan Gambino

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/alfred-w-crosby-on-the-columbian-exchange-98116477/?no-ist

Note: For the bottom image.

Library of Congress

Les voyages dv sievr de Champlain Xaintongeois,

capitaine ordinaire pour le Roy, en la marine. Divisez en devx livres.

ou, Iovrnal tres-fidele des observations faites és descouuertures

de la Nouuelle France

by Samuel de Champlain, circa 1605

https://www.loc.gov/item/22006274/

Book page: 80, Digital page: 112/436

Note: For book frontipiece and credits.

and

Plimoth Patuxet Museums

Port St. Louis (map)

https://plimoth.org/yath/unit-1/port-st-louis

Note: For the text and map.

(Ipswich)

Historic Ipswich

The Great Dying 1616-1619, “By God’s visitation, a Wonderful Plague.”

https://historicipswich.net/2023/11/17/the-great-dying/

Indian Narratives: Containing a Correct and Interesting History of the Indian Wars,

From the Landing of Our Pilgrim Fathers, 1620, circa 1854

by Henry Trumbull, Susannah Willard, and Zadock Steele

https://archive.org/details/indiannarrative00steegoog/page/n10/mode/2up

Book page: 76, Digital page: 87/295

Note: For the text.

Closer to Home in New England

(2) — seven records

Mayflower 400

Native America and the Mayflower: 400 years of Wampanoag History

https://www.mayflower400uk.org/education/native-america-and-the-mayflower-400-years-of-wampanoag-history/

Note: For the text.

GBH News

Reframing The Story Of The First Encounter Between

Native Americans And The Pilgrims

by Bob Seay

https://www.wgbh.org/news/local/2019-11-28/reframing-the-story-of-the-first-encounter-between-native-americans-and-the-pilgrims

Note: For the text.

Plimoth Patuxet Museums

Map of Wampanoag Country in the 1600s

https://plimoth.org/yath/unit-1/map-of-wampanoag-country-in-the-1600s

Note: For the map image.

Hathi Trust

Historical, Poetical and Pictorial American scenes:

Principally Moral and Religious: Being a Selection of Interesting Incidents in American History to Which is Added a Historical Sketch of Each of the United States, 1850

by John W. Barber and Elizabeth G. Barber

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiuo.ark:/13960/t00057646&seq=199

Book page: 183, Digital page: 199/254

Note: For the text and the image.

History of Ipswich, Essex and Hamilton

by Joseph Barlow Felt, 1834

https://archive.org/details/historyofipswich00felt/page/2/mode/2up

Book page: 2, Digital page: 24/404

Note: For the text (pull-quote).

(LAPM)

Leiden American Pilgrim Museum

https://leidenamericanpilgrimmuseum.org/en

Note: For the illustration of the Wampanoag hut.

(LMTTM)

Lies My Teacher Told Me

by James W. Loewen

https://www.google.pt/books/edition/Lies_My_Teacher_Told_Me/5m23RrMeLt4C?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA1&printsec=frontcover

Book pages: 70-92

Note: Chapter 3: “The Truth About The First Thanksgiving”

First Encounters With The Pilgrims

(3) — two records

GBH News

Reframing The Story Of The First Encounter Between Native Americans And The Pilgrims

by Bob Seay

https://www.wgbh.org/news/local/2019-11-28/reframing-the-story-of-the-first-encounter-between-native-americans-and-the-pilgrims

Note: For the text.

The Pilgrims arrive at Plymouth, Massachusetts on board the Mayflower,

November 1620 (painting)

by W.J. Aylward

https://www.historynet.com/how-collectivism-nearly-sunk-colonies/landing-of-the-pilgrims/

Note: For the painting image.

These People Were Different.

(4) — two records

GBH News

Reframing The Story Of The First Encounter Between Native Americans And The Pilgrims

by Bob Seay

https://www.wgbh.org/news/local/2019-11-28/reframing-the-story-of-the-first-encounter-between-native-americans-and-the-pilgrims

Note: For the text.

Mayflower 400

Native America and the Mayflower: 400 years of Wampanoag History

https://www.mayflower400uk.org/education/native-america-and-the-mayflower-400-years-of-wampanoag-history/

Note: For the text.

Discovering Indian Corn …and Graves

(5) — five records

National Geographic

A few things you (probably) don’t know about Thanksgiving

by Becky Little

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/151121-first-thanksgiving-pilgrims-native-americans-wampanoag-saints-and-strangers

Note: For the text.

Interesting Events in the History of The United States: being a selection of

the most important and interesting events which have transpired…

by John Warner Barber, 1798-1885

https://archive.org/details/intereventshistus00barbrich/page/n5/mode/2up

Note: For text and the illustration, Discovering Indian Corn.

(LMTTM)

Lies My Teacher Told Me

by James W. Loewen

https://www.google.pt/books/edition/Lies_My_Teacher_Told_Me/5m23RrMeLt4C?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA1&printsec=frontcover

Book pages: 70-92

Note 1: Chapter 3 for text, The Truth About The First Thanksgiving

Note 2: The travel map for Squanto was adapted from graphics on page 88.

Encyclopædia Britannica

Wampanoag People

Massasoit Meeting English Settlers

from ‘Lives of Famous Indian Chiefs’ by Norman B. Wood, 1906

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Wampanoag#/media/1/635211/179338

Note: For the image.

(NEFTH)

The National Endowment For The Humanities

Who Were the Pilgrims Who Celebrated the First Thanksgiving?

by Craig Lambert

https://www.neh.gov/humanities/2015/novemberdecember/feature/who-were-the-pilgrims-who-celebrated-the-first-thanksgiving

Note: For the text.

The Wampanoag Confederacy of Massasoit Sachem

(6) — seven records

Primary Source Learning:

The Wampanoag, the Plimoth Colonists & the First Thanksgiving

https://primarysourcenexus.org/2021/11/primary-source-learning-wampanoag-plimoth-colonists-first-thanksgiving/

Note: For the image of Massasoit And His Warriors

Massasoit

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Massasoit

Note: For the text.

The Conversation

The First Pilgrims and the Puritans Differed in Their Views on Religion,

Respect for Native Americans

by Michael Carrafiello

https://theconversation.com/how-the-first-pilgrims-and-the-puritans-differed-in-their-views-on-religion-and-respect-for-native-americans-240974

Note: For the text.

Images for the Massasoit collage —

Hathi Trust

Historical, Poetical and Pictorial American scenes:

Principally Moral and Religious: Being a Selection of Interesting Incidents in American History to Which is Added a Historical Sketch of Each of the United States, 1850

by John W. Barber and Elizabeth G. Barber

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiuo.ark:/13960/t00057646&seq=32

Book page: 16, Digital page: 32/254

Note: For the image of Massasoit.

and

The Massachusetts Historical Society

A Map of New-England (Woodcut)

Attributed to John Foster, 1677

https://www.masshist.org/database/68

Note 1: Originally published in William Hubbard’s Narrative of the Troubles with the Indians. Note 2: The Crown, indicates the royal seat of Massassoit, the Sachem of the Wampanoags, and is drawn between the two branches of the Sowams River.

and

File:Profile Rock (Assonet).jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Profile_Rock_(Assonet).jpg

Note 1: Image, 1902 postcard photo showing Profile Rock; scanned from a private collection.

Note 2: …it was thought to be that of the Wampanoag Chief Massasoit Sachem, from: https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/profile-rock

Samoset, the Abenaki Native American

(7) — two records

Samoset

Samoset arriving at Plymouth Colony in 1621

by Artist unknown

https://kids.britannica.com/kids/article/Samoset/601202

World History Encyclopedia

Samoset

https://www.worldhistory.org/Samoset/

Note: For the text.

Tisquantum, Who is Also Known as Squanto

(8) — seven records

Antique Print Club

Tisquantum. or Squanto, the Guide and Interpreter

by Charles de Wolf Brownell, circa 1864

https://www.antiqueprintclub.com/Products/Antique-Prints/Historic-Views-People/Americas-Canada/Tisquantum-or-Squanto,-the-guide-and-interpreter-c.aspx

Note 1: For the antique image of Tisquantum. or Squanto.

Note 2: “Rare wood engraving with contemporary hand color, from Charles de Wolf Brownell’s ‘The Indian Races of North and South America: comprising an account of the principal aboriginal races; a description of their national customs, mythology, and religious ceremonies; the history of their most powerful tribes, and of their most celebrated chiefs and warriors…’,

published in Hartford, Connecticut in 1864 by Hurlbut, Scranton & Co.”

Artwork of Málaga in 1572 —

40 years before Tisquantum was delivered there in slavery

Extracted from:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Squanto

Notes: Georg Braun; Frans Hogenberg: Civitates Orbis Terrarum, Band 1, 1572 (Ausgabe Beschreibung vnd Contrafactur der vornembster Stät der Welt, Köln 1582; [VD16-B7188) Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg

(LMTTM)

Lies My Teacher Told Me

by James W. Loewen

https://www.google.pt/books/edition/Lies_My_Teacher_Told_Me/5m23RrMeLt4C?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA1&printsec=frontcover

Book pages: 70-92

Note 1: Chapter 3: “The Truth About The First Thanksgiving”

Note 2: For the map from page 88, which we adapted for this chapter.

Mayflower 400

Native America and the Mayflower: 400 years of Wampanoag History

https://www.mayflower400uk.org/education/native-america-and-the-mayflower-400-years-of-wampanoag-history/

Note: For the text.

(NEFTH)

The National Endowment For The Humanities

Who Were the Pilgrims Who Celebrated the First Thanksgiving?

by Craig Lambert

https://www.neh.gov/humanities/2015/novemberdecember/feature/who-were-the-pilgrims-who-celebrated-the-first-thanksgiving

Note: For the text.

Pilgrim Fathers and Squanto, the Friendly Indian

after an Illustration by C. W. Jefferys, 1926

https://www.art.com/products/p53691947530-sa-i8600719/pilgrim-fathers-and-squanto-the-friendly-indian-after-an-illustration-by-c-w-jefferys-1926.htm

Note: For the illustration.

Hobbamock

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hobbamock#Hobomok_comes_to_live_with_English

Note: For the text about Squanto.

Hobomok, A Pneise of the Pokanoket

(9) — three records

Hobbamock

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hobbamock#Hobomok_comes_to_live_with_English

Note: For the text.

(LMTTM)

Lies My Teacher Told Me

by James W. Loewen

https://www.google.pt/books/edition/Lies_My_Teacher_Told_Me/5m23RrMeLt4C?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA1&printsec=frontcover

Book pages: 70-92

Note: Chapter 3: “The Truth About The First Thanksgiving”

The Conversation

The First Pilgrims and the Puritans Differed in Their Views on Religion, Respect for Native Americans

by Michael Carrafiello

https://theconversation.com/how-the-first-pilgrims-and-the-puritans-differed-in-their-views-on-religion-and-respect-for-native-americans-240974

Note: For the text.

Very Faithful in Their Covenant of Peace

(10) — three records

Hand-colored woodcut of Edward Winslow visiting Chief Massasoit.

https://www.bostonglobe.com/ideas/2017/11/19/after-first-thanksgiving-things-went-downhill/vvDRodh9iKU7IB2Wegjt8J/story.html

Note: For the image.

The British Empire

Plymouth Colony in 1630

https://www.britishempire.co.uk/maproom/massachusetts/massachusetts3.htm

Note: For the image.

Portrait of Plymouth Colony Governor Edward Winslow

Attributed to the school of Robert Walker, circa 1651

File:Edward Winslow.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Edward_Winslow.jpg

Note: For the portrait of Edward Winslow.