This is Chapter Three of nine. Edward Doty was a farmer, but he is sometimes also written of as being a yeoman (which is the same as a farmer), or sometimes as a plantor. (With the ‘or’ suffix spelling, plantor is likely an antique mis-spelling).

He was never a ‘Capital P’ Planter — which is something different, being a more elevated class of (usually tropical) plantation owners.

“What is the difference between a colonial farmer & a Planter? The difference between a colonial farmer and a Planter is a farmer worked in small, family-run farms. Farmers also cleared land, dug ditches, built fences and farm buildings, plowed, and did other heavy labor. Planters were wealthy, educated men who oversaw the operations on their large farms, or plantations.” (IPL, Learneo Services) (1)

Mr. Hot Under The Collar?

You Prigger! No I’m not , you’re a Prancer!! You’re a Doxie! Is that so?! Gilt! Rum Dubber!! You’re a Palliard and always will be! Your family are Clapperdogeons! [Faux Gasp] You Filching Cove! You should talk, you’re a Filching Mort! You’re a Lubber and so are all your Lollpooping friends! Rook! Rook! Rook!

…And so it goes, on and on in every era… These are just a few of the Colonial Era insults that used to be bandied about by some of our forebears. The Offended might have occasionally whispered under their breath that The Offender was A Gentlleman of Three Outs. (See footnotes).

We mentioned in the last chapter that Edward Doty had a history of being in court frequently in the Plymouth Colony being on both sides of things. As an example of a typical case, here is an excerpt from The Plymouth Colony Archive Project, from the Records of the General Court 1 April 1633, Records of Plymouth Colony 1:12 — “William Bennet accuses Dowty ‘of New Plymouth’ of slander by calling him a rogue. 😡 The foreman of the jury, Josuah Pratt found Dowty guilty and fined him 50 shillings, plus 20 for ‘the King’ and gave him eight month to make payment”.

An intriguing entry from 1643, (about Wolf Traps, yikes!) notes the following, “At a Townes meeting holden the xth ffebruary 1643 It is agreed That wolfe traps be made according to the order of the Court in manner following, That one be made at Playne Dealing — by Mr Combe, Mr Lee ffrancis Billington Georg Clark John Shawe and Edward Dotey”.

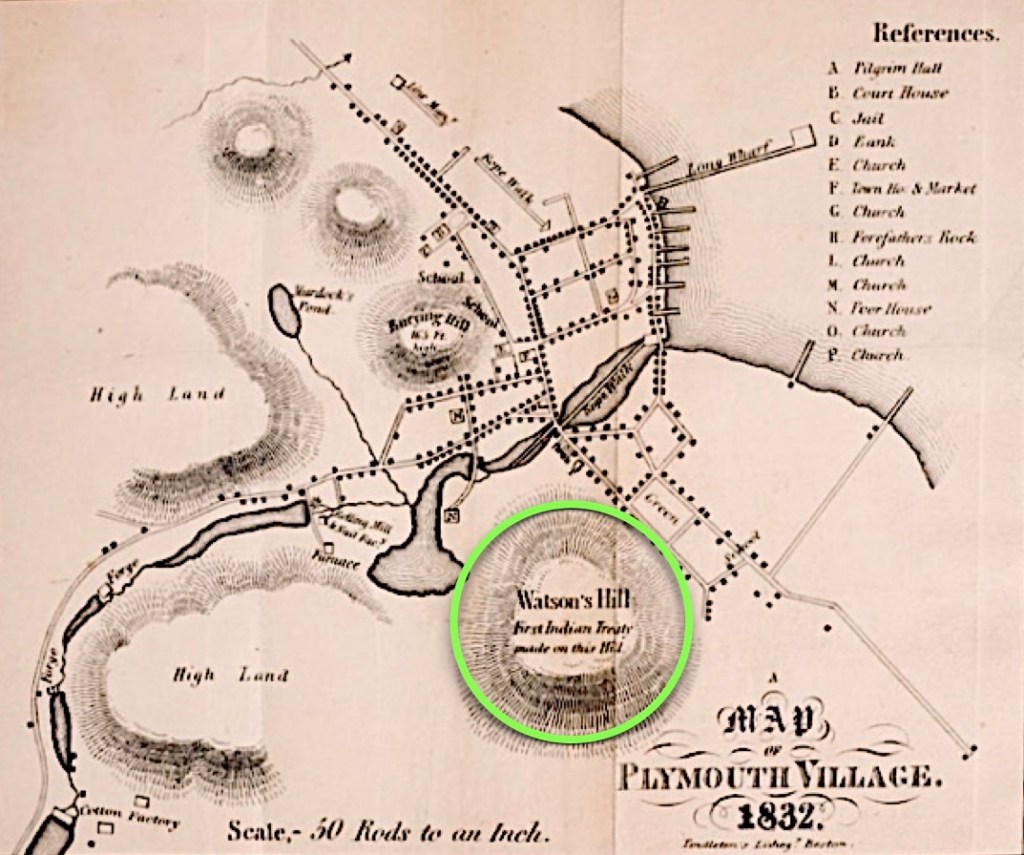

Near Watson Hill “…in 1624, Edward received his share of land allotment [for a home lot] and in 1627, in an allotment given to “heads of families and young men of prudence…” Edward was, also, given a share, even though he was unmarried, which shows him to have gained the confidence of the governor.” (Mayflower Ancestors)

which clearly shows where Edward Doty began his real estate holding in Plymouth, with land near Watson’s Hill.

Watson Hill is uniquely remembered because it is the vantage point from which the Native Person Samoset first observed the Pilgrims. “Stephen Hopkins, who had previously lived at Jamestown and, through interaction with the Powhatan tribe of Virginia, knew a little of the Algonquian language Samoset spoke”.(World History Encyclopedia) This resulted in Samoset staying in Hopkins’s home that evening, which is the same home that Edward Doty was also living. We speculate, that through his association with first Samoset, and then Squanto, that perhaps Doty favored Watson Hill as his home site. We cover much about the relationship between the Pilgrims and Native Peoples in the [same-named] chapter The Pilgrims — The Native Peoples. (2)

Whatever Happened to Edwards’s First Wife?

Plymouth Archives have Edward Doty records for everything from court cases, to land-dealing records, to the birth of his children… it’s actually a bit exhausting to wade through all of it. That may be, but as we wrote, there are many straightforward records of his real estate transactions in the Plymouth documents. He left much property to his children upon his death, which we will review in the later chapter, The Doty Line, A Narrative — Four.

Edward Doty had two wives, but there are no credible surviving records about who wife #1 actually was. There has been speculation that his first wife was in England, but if that were true, historians should be able to locate something? However, the fact that Edward Doty’s origins in England are also quite obscure, doesn’t help matters much, does it? He could have married someone who arrived on a later ship?

The issue with that is the timing —Edward Doty received land in 1623, but both he and Edward Leister are listed under Stephen Hopkins’s name. This leads us to believe that neither man was yet married, probably because their indentures to Hopkins were coming to an end. In the 1627 Division of Cattle, as with our other Pilgrim ancestor George Soule, if Doty had been married then, his wife would have been entitled to an additional share. Yet, no spouse is listed for him. (Could have had a very short marriage between 1623 and 1627? Perhaps.) About seven more years would pass before he would meet his wife #2. During this interval, many, many ships came to the New England Colonies during the Great Migration. They brought immigrants to the far north of Maine, all the way south to and beyond Jamestown, Virginia. Some of these ships did come through Plymouth.

If indeed Doty had a wife in the Plymouth Colony before he married wife #2 in 1635, then certainly Governor William Bradford would have recorded this in his manuscript, Of Plimoth Plantation. It is highly unlikely that under the meticulous and watchful eyes of Bradford, that Doty’s first marriage would have been unobserved, much less disregarded, but it could have happened. (3)

Comment: The following section below is adapted from a post made at Fine Artist Made, (see footnotes).

Edward Doty Wasn’t The Only Person Who Could Get Upset

— The Incident At Ipswich, England

Back in England, by 1630, Britain had already been entrenched, for a number of years, in a period of political turmoil, social unrest and economic uncertainty. On top of that, the Church of England, in consort with the Crown, had launched a campaign of religious persecution against a growing Puritan reform movement, whose mission was to revitalize a church grown stale, tyrannical and corrupt. The Great Migration of Puritans to British North America had begun, and would continue fitfully until the pending English Civil War.

The situation worsened for the Puritans in 1633, with the appointment of William Laud, a fierce opponent to their cause, as the Archbishop of Canterbury. They would need to take their chances in the untested wilderness of the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

The process, technicalities and red tape involved with preparations for a voyage of this magnitude were likely frustrating and expensive. Passengers (Puritans and Others) had to acquire licenses and documents to pass the port — then locate a ship. Finding an appropriate vessel would have involved an intensive search followed by serious negotiations. They had to procure provisions for their passage, as well as for their first year in New England. All this by necessity must have been accomplished surreptitiously.

Early in February 1634, two vessels were moored in Ipswich Harbor on the estuary of the Orwell River. Their passenger lists consisted largely of single men, married couples, and families — as many children as adults; some as young as one year old. They were middle class artisans and farmers. The first ship, called the Francis* was commanded by Master John Cutter and carried 84 passengers. The other was the Elizabeth with 101 passengers and Master William Andrewes at her helm. These two captains were planning to make their passage in tandem for their mutual benefit and safety. Their ships, rigged for a lengthy uncertain voyage, suddenly had their passages blocked.

(*Please see the last paragraph at the end of this chapter).

What happened was this: there was immediate opposition to this “progressive” contingent by the conservative officials in the Church of England, (who felt no sympathy for the Puritan’s case). On February 4, the Archdeacon of Suffolk’s agent, Henry Dade, the Commissary of Suffolk, wrote a letter from his office in Ipswich, to the Church of England’s principal leader, the Archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud. Dade reported that two ships were about to sail from Ipswich Port with men and provisions for their abiding in New England, and that in each ship “are appointed to go about six score men.” He supposed they were debtors or persons discontented with the government of the Church of England.

[Our observation: It seems Dade had worked himself up into quite a frothy state.] He told the Archbishop that his intelligence had informed him, that some 600 more were planning to shortly follow and described the “ill effects of suffering such swarms going out of England could cause; that trade would be overthrown and persons indebted would flee to New England to avoid bankruptcy and be treated as religious men for leaving the kingdom because they could not endure the ceremonies of the church.”

He blamed the Puritan minister, Samuel Ward, for inciting desire among his flock to relocate to Massachusetts. Ward was stationed in the ancient church of St. Mary-le-Tower, the civic church of the Corporation of Ipswich. The records of the Privy Council show that a warrant for tying up the two Ipswich vessels was issued within the week. A few days later, on February 14, similar steps were taken for the detention of ten other ships lying in the Thames near London — all under similar charters for Massachusetts Bay Colony.

(Here is where we invoke long story short…) After much drama, these conditions were imposed on everyone for the voyages:

- If anyone blasphemes or profanes the holy name of God, they shall be severely punished.

- On the ship, everyone must attend when the “Booke of Common Prayer” (established in the Church of England) were said at both Morning and Evening Prayers.

- All persons must have the ‘Certificate from the officers of the port’ where they departed, have taken both the oath of allegiance and supremacie (the belief that a particular group is superior to others, and should dominate them).

- That upon their return to this Kingdom they certify to the Board, the names of all persons transported, together with their proceedings in the execution of the aforesaid articles.

Finally, in mid to late April 1634, once the powers that be had sufficiently flexed their muscles, the Francis and Elizabeth set sail. Plying the vast Atlantic without further incident or loss of life, they entered the clear unfettered waters of the Massachusetts Bay some five to ten weeks later.

Then by November, Samuel Ward (thanks to Dade’s efforts), was banned from preaching for life for encouraging immigration to New England. There were riots in the streets of Ipswich. The Corporation of Ipswich refused to replace Ward, paid his stipend for life and after his death in 1640, supported his widow and eldest son who could not work himself. In 1637, Ward’s compatriot, Timothy Dalton, after his own suspension, immigrated to New Hampshire.

In the end, the Henry Dade as the Commissary of Suffolk’s unyielding persecutor of the Puritans of Ipswich — this would prove to be undoing. Amidst charges of corruption, oppression and extortion brought by a friend of Ward’s, a humble Puritan cobbler, he was compelled to resign his posts. (The cobbler himself was faced with excommunication and sought asylum in New England).

As for Dade’s accomplice, William Laud, the Archbishop of Canterbury — in 1645, in the midst of the English Civil War, in part, for his crimes against the Puritans — he was beheaded.

The importance of relating this saga about strife and bureaucracy in England, with the ship Francis, is that this ship brought our 9x Great Grandmother Faith Clarke (along with her father Thurston Clarke), to the Plymouth Colony. The good news is, that very soon, we will meet the new Mrs. Doty. (4)

Following are the footnotes for the Primary Source Materials,

Notes, and Observations

(1) — one record

IPL, Learneo Services

What Is The Difference Between A Colonial Farmer And A Planter?

https://www.ipl.org/essay/What-Is-The-Difference-Between-A-Colonial-17E05078F5C70CC6

Note: For the text.

Mr. Hot Under The Collar?

(2) — seven records

Medium

The Art and Science of Swearing

by Robert Roy Britt

https://medium.com/wise-well/the-art-and-science-of-swearing-5fadb0b6c979

Note: For the insult cloud artwork.

10 Colonial Insults for Lollpools, Doxies and Prigs

by The New England Historical Society

https://newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/lollpoops-doxies-prigs-ten-colonial-insults/#google_vignette

Note: For the reference, you _______!

The Plymouth Colony Archive Project

EDWARD DOTEY (DOTEN, DOTTEN, DOTY, DOWTIE)

of Plymouth

http://www.histarch.illinois.edu/plymouth/DOTEYED.htm

Note: For the text.

Mayflower Ancestors

Edward Doty & Descendants

Edward Doty: 1599 – 1655

https://gardenmayflowerancestors.wordpress.com/

Note: For the text.

History of the Town of Plymouth,

from its first settlement in 1620, to the present time

by James Thacher, circa 1835

https://archive.org/details/historyoftownofp03thac/page/n11/mode/2up

Note: For the foldout map at the beginning of the book.

World History Encyclopedia

Samoset

https://www.worldhistory.org/Samoset/

Note: For the text.

Interview of Samoset With The Pilgrims, book engraving

by Artist unknown, circa 1853

File:Interview of Samoset with the Pilgrims.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Interview_of_Samoset_with_the_Pilgrims.jpg

Note: For the image of Interview of Samoset With The Pilgrims

Whatever Happened to Edwards’s First Wife?

(3) — two records

The Plymouth Colony Archive Project

EDWARD DOTEY (DOTEN, DOTTEN, DOTY, DOWTIE)

of Plymouth

http://www.histarch.illinois.edu/plymouth/DOTEYED.htm

Note: For the text.

State Library of Massachusetts Digital Collections

Of Plimoth Plantation: manuscript, 1630-1650

https://archives.lib.state.ma.us/items/db0e9f79-477c-4a4c-979b-359c2be1d4ad

Note 1: The notation for Edward Doty having a wife from a second marriage is located very close to the end of the book.

Note 2: There are no page numbers, but the page is possibly — Digital page:534/546, left column.

Note 3: The document is digitized and available as a .pdf download at the above link, file name: ocn137336369-Of-Plimoth-Plantation.pdf

Edward Doty Wasn’t The Only Person Who Could Get Upset

— The Incident At Ipswich, England

(4) — seven records

Fine Artist Made

Incident at Ipswich, Part 1

https://www.fineartistmade.com/blog/blog-detail.php?Incident-at-Ipswich-part-1-68

and

Incident at Ipswich, Part 2

https://www.fineartistmade.com/blog/blog-detail.php?Incident-at-Ipswich-part-2-70

by Patrick Mealey and Joyce Jackson

Note: For the text.Historic UK

Times Literary Supplement

The Pilgrim Fathers Boarding the Mayflower for their Voyage to America

by Bernard Gribble, (1872–1962)

https://www.the-tls.com/history/early-modern-history/mayflower-voyage-400

Note: For the ship painting.

British Heritage Travel

From East Anglia to A City Upon A Hill

https://britishheritage.com/from-east-anglia-to-a-city-upon-a-hill

Note: Primedia Archive, for the fleeing Puritans in a boat image.

The Life and Death of William Laud

https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofEngland/The-Life-and-Death-Of-Wiliam-Laud/

Note: For the Laud portrait.

Boat on Beach, Sunset

by John Moore of Ipswich (1821–1902)

https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/boat-on-beach-sunset-12029

Note: For the Ipswich, England harbor scene.

The Digital Puritan

Samuel Ward

https://digitalpuritan.net/samuel-ward/

Note: For the Samuel Ward portrait.