This is Chapter Four of seven, as we continue with the unfolding history of the McClintock family.

This chapter of our narrative has two parts. The first part is about wars and conflict; the second part, peace and community. It is unusual for us to find so many records about an ancestor who was not well known to history. This is due to the fact that William McClintock was deeply involved as a Selectman for the town of Derryfield in both governmental and religious matters, (and that the records have survived!)

Before the American Revolution, a town like Chester had a widely scattered population. The History of New Hampshire states, that “men, women and children had been accustomed to walk six and eight miles to attend [religious] services.” (Ya gotta hand it to these ancestors… show of hands for anyone who does this today on a regular basis…) (1)

In Times of War, We Suffer

In the year 1748, there was palpable fear in Tyng’s Township of Indians (Native Peoples) attacking the “There seems to have been more fear of the Indians this year than in any other. There were several garrisons kept in town. The house now occupied by Benjamin Hills still has the port-holes through the boarding…” (These portholes are related to the sides of a wooden ship which was repurposed to build the wall of a house. The portholes were windows which the setters would shoot through toward people they viewed as aggressors.) Below is an example of a petition that our ancestors, who appear to have lived far from the town center. (History of Old Chester)

Our ancestors were inhabiting the lower reaches of the British New Hampshire Province. The upper portion was a border area, sparsely filled with the French, who had their various alliances with Native Peoples. Hence, the region was a border area filled with conflict, some of it percolating down to southern New Hampshire. “In British America, wars were often named after the sitting British monarch, such as King William’s War or Queen Anne’s War. There had already been a King George’s War in the 1740s during the reign of King George II, so British colonists named this conflict after their opponents, and it became known as the French and Indian War”. (Wikipedia) (2)

Military Service in Two Wars

The French and Indian War

“The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years’ War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. Two years into the war, in 1756, Great Britain declared war on France, beginning the worldwide Seven Years’ War. At the start of the war, the French colonies had a population of roughly 60,000 settlers, compared with 2 million in the British colonies. The outnumbered French particularly depended on their native allies. The British colonists were supported at various times by the Iroquois, Catawba, and Cherokee tribes, and the French colonists were supported by Wabanaki Confederacy members Abenaki and Mi’kmaq…” (Wikipedia)

London, England, by Benjamin West,

(oil on canvas, unfinished sketch), Winterthur Museum, Winterthur, Delaware.

From left to right: John Jay, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Henry Laurens, and William Temple Franklin. The British commissioners refused to pose, and the picture was never finished.

Records show that that William and his twin brother Michael were involved in military service for two wars during the decades of the 1740s through the 1770s. William McClintock achieved the rank of Sergeant, and his brother Michael achieved the rank of Captain. We found records of military payments in pounds and shillings, made to William McClintock and his brother Michael. Browne writes in the Early Records of the Town of Derryfield, “Paid by the Sundrey persons hereafter Named to Nethaniel Martin Teopilus Griflfen & Nat Baker as volenters men they went to Noumber four about the Retreet from Ty — are as followeth

William mc Clintok 0 6 0 0.” (See the notes from the Harvard Library at the end of this section, for an explanation about payments).

The conflict William was paid for was the siege of “Number four about the retreat from Ty [Tyngstown] which “was a frontier action at present-day Charlestown, New Hampshire, during King George’s War”. (Collections of The Bennington Museum, Bennington, Vermont)

The Association Test

“In March 1776 the Continental Congress resolved that all persons who refused to sign the Association to defend the cause of the Colonies should be disarmed. To put this resolve into effect, the New Hampshire Committee of Safety directed the local authorities, usually the selectmen, to have all adult males sign the Association and to report the names of those who refused to sign. The end result amounted to a census of the adult male inhabitants of New Hampshire for 1776…” (Inhabitants of New Hampshire 1776)

From this document we learned that both Michael(Nicheall) and William signed the Association, and that they were both still living in Derryfield. William’s sons Alexander and John also signed, but were then living in the nearby town of Hillsborough.

(Image courtesy of The Bennington Museum).

The Battle of Bennington, Revolutionary War

John Stark of Derryfield, New Hampshire was friends with both of the McClintock brothers as he had served with them as one of the town administrators during the 1760s. During the Revolutionary War, he “was commissioned [as]a brigadier general of the New Hampshire militia and was ordered to lead a force to Bennington, there to cooperate with Seth Warner’s Green Mountain Boys posted at Manchester.

Stark agreed to take the independent command, so long as he was issued a commission from only New Hampshire. He refused to take orders from Congress or from any Continental officer. As the historian Richard Ketchum has emphasized, “the effect was startling. Within six days, twenty-five companies – almost fifteen hundred men – signed up to follow him, some of them even walking out of a church service when they heard of his appointment. [In August 1777] General Stark marched his force to Bennington – a small village that one British officer called ‘the metropolis of the [future] state of Vermont’.” (Champlain Valley NHP, see footnotes).

From the Early Records of the Town of Derryfield, “Paid by indeviduels to hold on John Nutt Enoch Harvey Theophilus Griffin & David Farmer and others went with General Stark at the Battel at Benenten are as folloeth (viz)

Micheal mc Clintok 1 2 0 0

William mc Clintok 1 4 0 0”

It’s unclear if William and Michael were paid in (£) Pound sterling, shillings, and pence, or in the scrip of the Continental Congress. “When the Second Continental Congress met in Philadelphia in 1775, it authorized the issue of bills of credit to the value of two million Spanish milled dollars as a way of funding the Revolutionary War. The Continental Congress granted a charter to create the Bank of North America in Philadelphia to issue the notes. Paul Revere of Boston engraved the plates for the first of these bills, which were known as Continental Currency. As had been the case in the days of Colonial Scrip, each of the colonies printed its own notes, some denominated in pounds, shillings, and pence, and others in dollars.” (Harvard Library)

Observations: In 1755, when the French and Indian War began, both of the brothers would have been 46 years old. When the conflicts for the Revolutionary War began in 1775, they would have been 68 years old. We thought that might be a bit too old to serve, but the records for the date of the Battle of Bennington correspond to gaps in their records with the town administration of Derryfield. So, even though they were older, it seems possible. Family Search records that the age range for Servicemen during the French and Indian War, and the Revolutionary War, was 16-60 years. Additionally, author Browne wrote in The History of Hillsborough, New Hampshire, 1735-1921,“An examination of this list made nearly a year after the battle of Lexington shows that… of the forty-seven men eighteen were over fifty years of age, and beyond the military limit, though this did not deter the most of them from entering the service sometime during the war.” (3)

William Wore Many Hats in Addition to His Tricorne Cap!

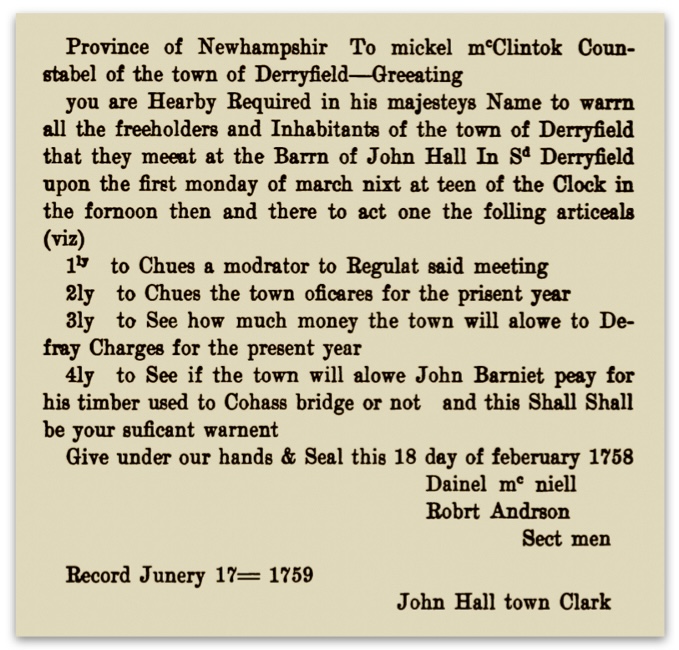

As we wrote about in the last chapter, our McClintock ancestors lived in an area that had several names (Tyng’s Township, circa 1727 > Derryfield, circa 1751 > Manchester, circa 1810). William McClintock was the most active member of the town administration and there are many records which feature his various responsibilities. From the book, the History of Manchester, 1735-1921, author Browne writes:

“…a board of officers known as “Select Men,” usually consisting of five of the most prominent men in the community, were chosen to look after matters in the intervals [between town meetings]. Finally these came to be elected for a year, and the meetings were made annual, unless some uncommon subject demanded a special meeting, and March, the least busy period of all the year for the tillers of the soil, was selected as the month in which to hold these gatherings. Soon the Selectmen became known as ‘The Fathers of the Town,’ a very apt term, considering that they were in truth masters of the situation and lawmakers as well as lawgivers.

The next officer of importance to the Selectmen, and we are not unmindful of the Moderator, who must have been the oldest official, was the person who was intrusted [sic] with the keeping of the records, the Clerk… There had to be men to keep the peace, and the restrictions were very rigid in those days, and these officers were called ‘Constables.’ As soon as the time came when money was needed to finance the public business taxes had to be assessed, which called for ‘Assessors,’ though the Selectmen usually performed this duty, and do until this day in most country towns. In order to obtain these taxes, men had to go out and collect them, for even then money was not paid over until called for, and this duty was performed for a time by the Constable. (The History of Hillsborough, 1735-1921)

Records for Michael and William McClintock were gathered from two sources: Early Records of the Town of Derryfield: Now Manchester, N. H. 1751 – 1782, and The History of Hillsborough, New Hampshire, 1735-1921).

| Role | Years | Broad duties |

| Assessor | 1751 | Raised money |

| Committees | 1751, 1754, 1769, 1778 | |

| Constable | 1756 | Collects taxes |

| Moderator | 1753, 1754, 1758, 1766, 1767, 1769, 1775 | Manages meetings |

| Preacher | 1759 | |

| Selectman | 1754, 1758 through 1760 1763 through 1765 1769 through 1772 | Administration |

| Surveyor of Highways | 1758, 1779 | Field work |

Michael McClintock had several roles over the years, but he seems to have spent more time doing other activities such as his agricultural work. With his brother being involved in local government more deeply, he must have been quite aware of what was going on at different times, but chose to keep a lower profile.

| Role | Years | Duties |

| Constable | 1757 through 1759 | Collects taxes |

| Deerkeeper | 1766 | |

| Surveyor of Highways | 1766 | Field work |

| Tithingman | 1752, 1760, 1761, 1771 | Preserves order during church services |

In January 1776, New Hampshire became the first colony to set up an independent government and the first to establish a constitution. (Wikipedia) By 1778, town records indicate that William McClintock was part of a committee involved in the framing a new state Constitution.

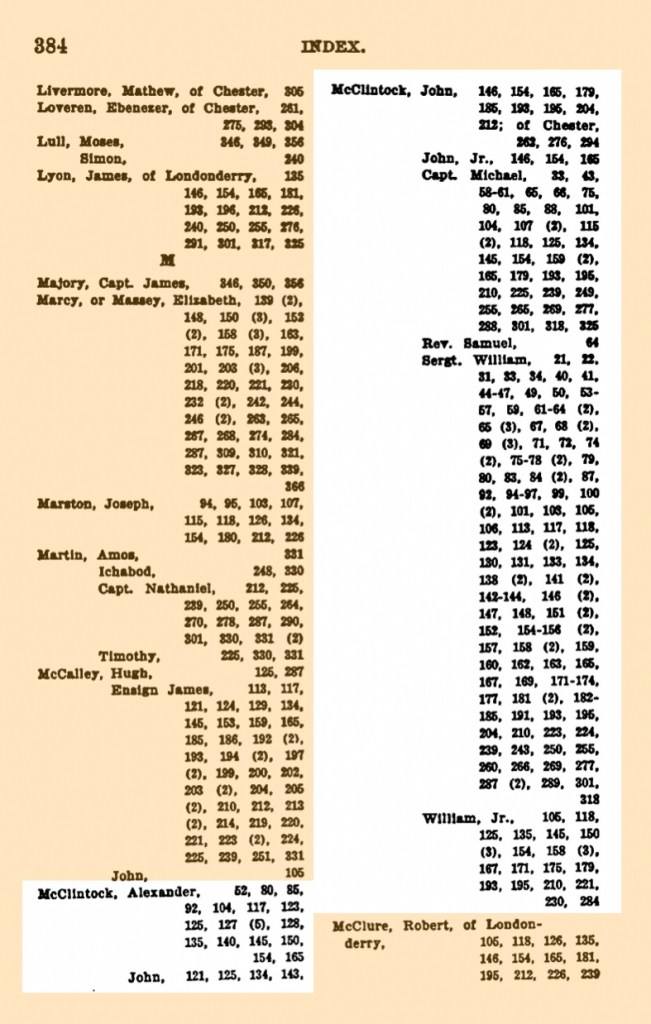

Comment: To create the above charts, we did an extensive analysis of the copious administrative records for both William and Michael McClintock. If interested in that level of detail, please see the many index entries listed in the footnotes of the Early Records of the Town of Derryfield: Now Manchester, N. H., 1751 — 1782, Volumes I and VIII. (4)

In Times of Peace, We Try to Build A Community

The Colonial Meeting House

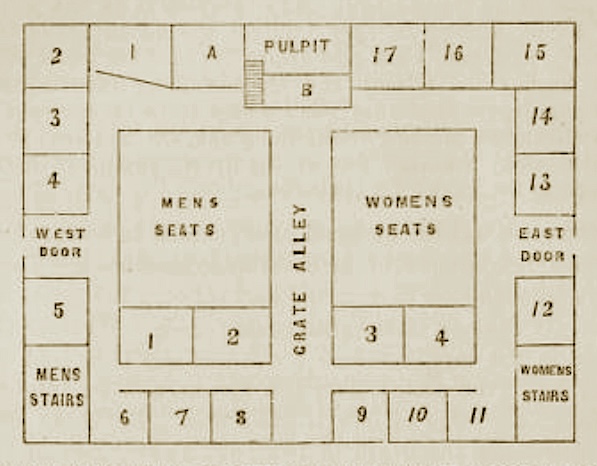

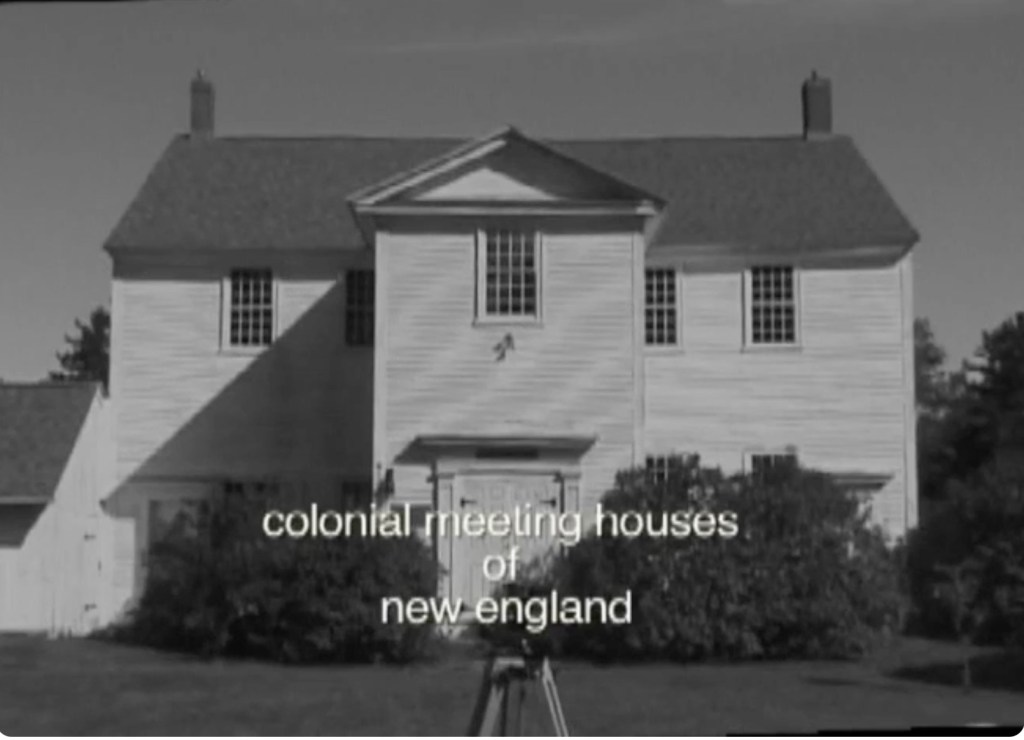

“A colonial meeting house was a meeting house used by communities in colonial New England. Built using tax money, the colonial meeting house was the focal point [central focus] of the community where the town’s residents could discuss local issues, conduct religious worship, and engage in town business.” [It] was usually the largest building in the town.

Most were almost square, with a steep pitched roof running east to west. There were usually three doors: The one in the center of the long south wall was called the Door of Honor, and was used by the minister and his family, and honored out-of-town guests. The other doors were located in the middle of the east and west walls, and were used by women and men, respectively. A balcony (called a gallery) was usually built on the east, south, and west walls, and a high pulpit was located on the north wall.

Following the separation of church and state, some towns architecturally separated the building’s religious and governmental functions by constructing a floor at the balcony level, and using the first floor for town business, and the second floor for church.

“They were simple buildings with no statues, decorations, stained glass, or crosses on the walls. Box pews were provided for families, and single men and women (and slaves) usually sat in the balconies. Large windows were located at both the ground floor and gallery levels. It was a status symbol to have much glass in the windows, as the glass was expensive and had to be imported from England”. (Wikipedia)

The following YouTube.com video, by photographer Peter Hoving, beautifully explains the layout and concepts behind New England Meeting Houses. Some of which he as photographed in New Hampshire.

Please click on this link to watch the above video:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dSgmQzbnkOU

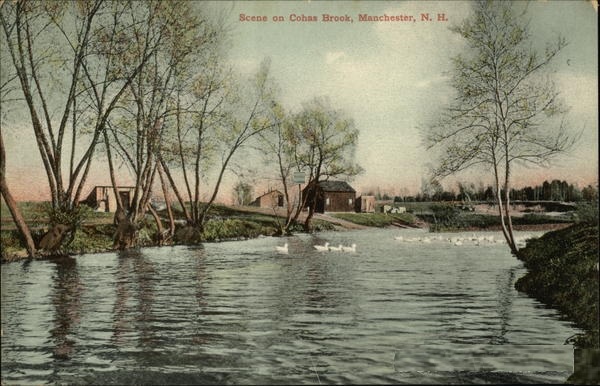

In the Early Records of the Town of Derryfield, in describing the period after the French and Indian War, “An era of prosperity had dawned upon the province, but unfortunately for the harmony and welfare of the new town two combative elements of human life made up the minds and sinews of the men of Derryfield. Its inhabitants consisted of two distinct races, the Scotch-Irish who had begun to settle within the bounds of its territory as early as 1720, with others following from time to time… while the grant of the Tyng township in 1735 called thirty or more families of the English colony of Massachusetts, the latter largely along the banks and at the mouth of Cohas brook.…

The Scotch Presbyterians, who somewhat outnumbered their contemporaries, were imbued with their set, vivid views of what constituted their civil and religious liberties, while the English in their belief were as rigid and dogmatical as they. We see the coloring of this difference of opinion coming to the surface almost immediately, for within a year of the granting of the charter a controversy arose relative to the building of a meeting-house and settling of a minister”.

The gist of this history seems to be that there were two groups of people who made up Derryfield: the Scotch Presbyterians, and the resettled English from Massachusetts. (Remember that Massachusetts had once long been an overlord of New Hampshire province). It seems that in an era when religious practice was a very strong component of people’s lives, both sides had resolute religious viewpoints.

In the town records of Derryfield, we saw William McClintock involved as early as 1752, in conducting Presbyterian religious services out of his home. Apparently, since the town lacked a meeting center, and a Preacher (as they termed it), it was not unusual to do religious services at one’s home, or even one’s barn. Additional town records indicate that the Selectman who administered the town were actively interviewing and seeking preachers throughout the 1750s. Occasionally they would find someone, but it seems that it was never a long-term solution.

In this era, town residents had been paying taxes and fees which were collected to provide for a a town center, i.e. a Meeting House. This was a normal New England circumstance — that a Meeting House would exist at the center of the village and this facility would be where town meetings, town administration, and religious services would be conducted. For myriad reasons that are not important now, locations would be chosen, taxes would be paid, things would be agreed to, and then at the next town meeting, all of it would be undone as different sides squabbled. This literally delayed construction for decades.

Comment: No wonder they couldn’t get a Preacher. Who would want to work in that environment if everyone was so inflexible and argumentative.

A meeting house building plan and site would eventually be agreed to, and construction begun, but the building was only used as the Meeting House for a short period, before being replaced by another structure, built by a new generation. Lost tax revenues due to the Revolutionary War didn’t help matters. (5)

A Rhum and A Sunset

Not everything was about war and politics. The book, The Town Church of Manchester records, “The records of Tyngstown contain an interesting account of the expense of the raising of the meetinghouse. [As monetary records for pounds and shillings] The first two items are —

To Joseph Blanchard for Rum & Provisions 2 5 3

To the Rev’d M’r Thomas Parker 2 0 0

After all our respect for the piety of the fathers, preaching seems to have been a secondary matter when it came to ‘rum and provisions.’ Rum was an important factor in that raising, for it constituted both the first and the last items in the bill of expenses. The last item is —

“Had of William McClinto for Raiseing 6 g’lls [gallons] of Rhum

at 18s per G’ll [gallon] @ 5 8 0”

After all, William was the descendant of a Glasgow ‘Maltman’ (a brewer).

I measured off 20 acres of Meadow and Swamp for

Matthew Patten

William McClintock in the meadow below his house to

Abraham Merrill and others for which McClintock

paid me a Dollar and I paid him

11/ Hampshire old Tenor for 1/2 a pint of Rum

December 28th, 1770 diary entry from

The Diary of Matthew Patten of Bedford, N.H.

Matthew Patten lived in Bedford, not very far from William McClintock. From the quote above, observe the odd words like Hampshire old Tenor to describe the form of payment. We forget that as America was being settled each province had it’s own currency. It must have been very confusing to travelers back then.

(Compiled from various Google image searches).

From the article, Money in The American Colonies, we learned from writer Ron Michener, “The monetary arrangements in use in America before the Revolution were extremely varied. Each colony had its own conventions, tender laws, and coin ratings, and each issued its own paper money. The units of account in colonial times were pounds, shillings, and pence (1£ = 20s., 1s. = 12d.). These pounds, shillings, and pence, however, were local units, such as New York money, Pennsylvania money, Massachusetts money, or South Carolina money and should not be confused with sterling. [the English currency]To do so is comparable to treating modern Canadian dollars and American dollars as interchangeable simply because they are both called dollars… after 1799, in which year a law was passed requiring all accounts to be kept in dollars or units, dimes or tenths, cents or hundredths, and mills or thousandths”.

In 1769, New Hampshire created five counties: Cheshire, Grafton, Hillsborough, Rockingham, and Strafford. Subsequently, much of the historical records have William and Michael McClintock in the records of both Hillsborough County and the city of Manchester. New Hampshire became a state in 1781. However, for most of their lives, they lived in the Province of New Hampshire, without a County, in the small town of Derryfield.

We are not sure how long either Michael McClintock or William McClintock lived. For Michael, we do know this — From the National Archives, “The census began on Monday, August 2, 1790, and was finished within 9 months.” In Derryfield, Hillsborough County, there is a record of a Michael McClintock living there with a woman. Both are recorded as being over 16 years of age. A general issue for genealogical research with this first census, is that it provides almost no detail, nor context. By the time 1790 rolled around, Michael would have been about 81 years old. It could be him, we just cannot say for sure. The last tax record we have for him is from the Derryfield history, for the Continental County and Town Tax for 1779-80.

As for William McClintock, the same tax record observation applies to him. We are not sure that he was still living by the time of the 1790 census, because there is no record of him being counted directly. He had five children and perhaps he could have been living in one of their homes? As we know with Michael… the 1790 census only records someone as being either over, or under 16 years of age, providing no further detail. However, since there was no listing for William McClintock we can assume that it is possible that he was probably no longer living by 1790.(6)

In the next chapter, we will meet our 4x Great Grandfather, John McClintock (Sr.), the youngest son of William and Agnes McClintock.

Following are the footnotes for the Primary Source Materials,

Notes, and Observations

(1) — one record

Colonists Walking to Church, 19th-Century Print

by James S. King

https://www.magnoliabox.com/products/19th-century-print-of-colonists-walking-to-church-f1299

Note: For the family image.

History of New Hampshire

by J. N. McClintock

https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_8e6FpX4eu1wC/page/130/mode/2up?q=%22men%2C+women+and+children+had+been+accustomed+to+walk+six+and+eight+miles+to+attend%22

Book page: 131, Digital page: 130/691

In Times of War, We Suffer

(2) — one record

History of Old Chester [N. H.] from 1719 to 1869

by Benjamin Chase 1799-1889

https://archive.org/details/historyofoldches00chas/page/558/mode/2up

Book page: 107, Digital page: 106/702

Note: For the Third Petition of 1748.

Military Service in Two Wars

(3) — nineteen records

French and Indian War

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_and_Indian_War

Note: For the text.

Louis-Joseph de Montcalm trying to stop Native Americans from attacking British soldiers and civilians as they leave Fort William Henry at the Battle of Fort William Henry

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Montcalm_trying_to_stop_the_massacre.jpg

Note: For the battle image.

American Commissioners of the Preliminary Peace Agreement

with Great Britain, 1783-1784, London, England, by Benjamin West

(oil on canvas, unfinished sketch), Winterthur Museum, Winterthur, Delaware

From left to right: John Jay, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Henry Laurens, and William Temple Franklin.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Treaty_of_Paris_(1783)#/media/File:Treaty_of_Paris_by_Benjamin_West_1783.jpg

Note: For the painting image. The British commissioners refused to pose, and the picture was never finished.

Office of The Historian of the Department of State

Treaty of Paris, 1763

https://history.state.gov/milestones/1750-1775/treaty-of-paris#:~:text=The%20Treaty%20of%20Paris%20of,to%20the%20British%20colonies%20there.

Note: For the data.

Fort at Number 4

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fort_at_Number_4

Note: For the reference.

Early Records of the Town of Derryfield: Now Manchester, N. H.

1782 — 1800, Volumes II and IX

by George Waldo Browne

https://archive.org/details/earlyrecordstow00nhgoog/page/n6/mode/2up

Book pages: 109-110, Digital pages: 129-131/425

Note: For the data. Descriptions of payment for year 1776 military service to “Noumber four about the Retreet from Ty” “the Battel at Benenten”.

Early Records of the Town of Derryfield: Now Manchester, N. H.

1782 — 1800, Volumes II and IX

by George Waldo Browne

https://archive.org/details/earlyrecordstow00nhgoog/page/n128/mode/2up

Book pages: 108-110, Digital pages: 129-131/425

Note: For payments due to military service.

This file confirms the above footnotes, for military service payments:

History of Hillsborough County, New Hampshire

History of Manchester

https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/23240/images/dvm_LocHist008921-00058-1?ssrc=&backlabel=Return&pId=38

Book page: 45-46, Digital page: 71-72/878

Note: For the data.

Inhabitants of New Hampshire, 1776

by Emily S. Wilson

https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/49199/images/FLHG_InhabitantsofNH-0071?ssrc=&backlabel=Return&pId=52151

Book pages: 4 and 71, Digital pages: 4/170 and 71/130

Note: For the data.

Battle of Bennington, August 16, 1777

by Alonzo Chappel.

https://bennington.pastperfectonline.com/webobject/A4B796E5-ADE8-455B-8DF7-217237214000

Note: For the battle painting.

Champlain Valley National Heritage Partnership

Threads of History

John Stark, The Hero of Bennington

https://champlainvalleynhp.org/2022/08/john-stark-the-hero-of-bennington/

Note: For the text.

Battle of Bennington

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Bennington

Note: For the data.

Early Records of the Town of Derryfield: Now Manchester, N. H.

1782 — 1800, Volumes II and IX

by George Waldo Browne

https://archive.org/details/earlyrecordstow00nhgoog/page/n128/mode/2up

Book pages: 108-110, Digital pages: 129-131/425

Note: For payments due to military service.

Harvard Library Curiosity Collections

American Currency, Continental Currency

https://curiosity.lib.harvard.edu/american-currency/feature/continental-currency

Note: For the text.

Stamp Act Congress

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stamp_Act_Congress

Note: For the data and artwork.

The History of Hillsborough, New Hampshire, 1735-1921

by George Waldo Browne

https://archive.org/details/historyofhillsbo01brow/page/110/mode/2up?view=theater

Book page: 111, Digital page: 110/567

Note: For the quote about military age over 50 years.

Ages of Servicemen in Wars

https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Ages_of_Servicemen_in_Wars

Notes: Revolutionary War Duration, 1776-1783 > Typical Years of Birth, 1757-1767 > Typical Ages 16 to 60

Note: For the data.

The History of Hillsborough, New Hampshire, 1735-1921

by George Waldo Browne

https://archive.org/details/historyofhillsbo01brow/page/n5/mode/2up?view=theater

Book pages: 225-226, Digital pages: Page numbers are inaccurate.

Note: For descriptions of Assessor, Selectman, Constable.

Manchester A Brief Record of its Past and a Picture of its Present…

by Maurice D. Clarke, 1875

https://archive.org/details/manchester00clarrich/page/n5/mode/2up

Book pages: 33-34, 38, Digital pages: Page numbers are inaccurate.

Note: For the text.

William Wore Many Hats in Addition to His Tricorne Cap!

(4) — three records

Winchester News

Chaos Reigns on Fourth Night of Town Meeting

https://winchesternews.org/20231118chaos-reigns-on-fourth-night-of-town-meeting/

Note: For the New England town meeting image.

Early Records of the Town of Derryfield: Now Manchester, N. H.

1751 — 1782, Volumes I and VIII

by George Waldo Browne

https://archive.org/details/earlyrecordstow01nhgoog/page/n4/mode/2up

Book page: 61, Digital page: 67/407,

Note: For Michael McClintock constable posting.

History of New Hampshire

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_New_Hampshire

Note: Regarding new state Constitutional issues

In Times of Peace, We Try to Build A Community

(5) — eight records

Colonial Meeting House

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colonial_meeting_house

Note: For the text.

History of Old Chester [N. H.] from 1719 to 1869

by Benjamin Chase 1799-1889

https://archive.org/details/historyofoldches00chas/page/96/mode/2up

Book page: 96, Digital page: 96/702

Note: For the architectural plan. The Ground Plan of the Old-Meeting House as Seated in 1754…

Colonial Meeting Houses of New England – (2007}

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dSgmQzbnkOU

Note: For the video.

Early Records of the Town of Derryfield: Now Manchester, N. H.

1751 — 1782, Volumes I and VIII

by George Waldo Browne

https://archive.org/details/earlyrecordstow01nhgoog/page/n4/mode/2up

Book pages: 10-11, Digital pages: 15/407

Note: For the description of the two different communities which made up Derryfield.

Credits for Church and Barn Gallery:

BIBLE, Irish — 1690

https://www.sothebys.com/en/buy/auction/2020/english-literature-history-childrens-books-and-illustrations/bible-irish-1690

and

Historic Ipswich

Mural depicting The Rev. John Wise of Ipswich

https://historicipswich.net/2022/11/15/john-wise/

and

English Historical Fiction Authors

Barn image cover artwork for The Red Barn Murder

by Regina Jeffers

https://englishhistoryauthors.blogspot.com/2014/05/the-red-barn-murder.html

Note: For the tvarious artworks.

Towns of New England and Old England, Ireland and Scotland … connecting links between cities and towns of New England and those of the same name in England, Ireland and Scotland

https://archive.org/details/townsnewengland02stat/page/n10/mode/1up

Book page: 120, Digital page: 120/225

Note: For the text.

A Rhum and A Sunset

(6) — six records

The Town Church of Manchester

by Thomas Chalmers, 1869 (1903 edition)

https://archive.org/details/townchurchofmanc00chal/page/n5/mode/2up

Book pages: Frontispiece and 26, Digital pages: 26/155

Note: For the photographs. Frontispiece photograph, and the Rhum quote.

The Diary of Matthew Patten of Bedford, N.H.

(Copied from Matthew Patten’s diary)

https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/23193/images/dvm_LocHist008938-00132-1?ssrc=pt&treeid=18269704&personid=635978899&usePUB=true&pId=256

Book page: 257, Digital page: 257/545

Note: For the text.

Money in the American Colonies

by Ron Michener, University of Virginia

https://eh.net/encyclopedia/money-in-the-american-colonies/

Note: For the text.

Boston Rare Maps

The Sotzmann-Ebeling Map of New Hampshire, Circa 1796

https://bostonraremaps.com/inventory/sotzmann-ebeling-new-hampshire-1796/

Note: To document the five original counties established in 1769.

The National Archives

1790 Census Records

https://www.archives.gov/research/census/1790

Note: For the data.

Michael McClintock

in the 1790 United States Federal Census

New Hampshire > Hillsborough > Hollis

https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/213949:5058?ssrc=pt&tid=18269704&pid=643749156

Digital page: 4/4, Right column, entry 1.

Note: For the data.