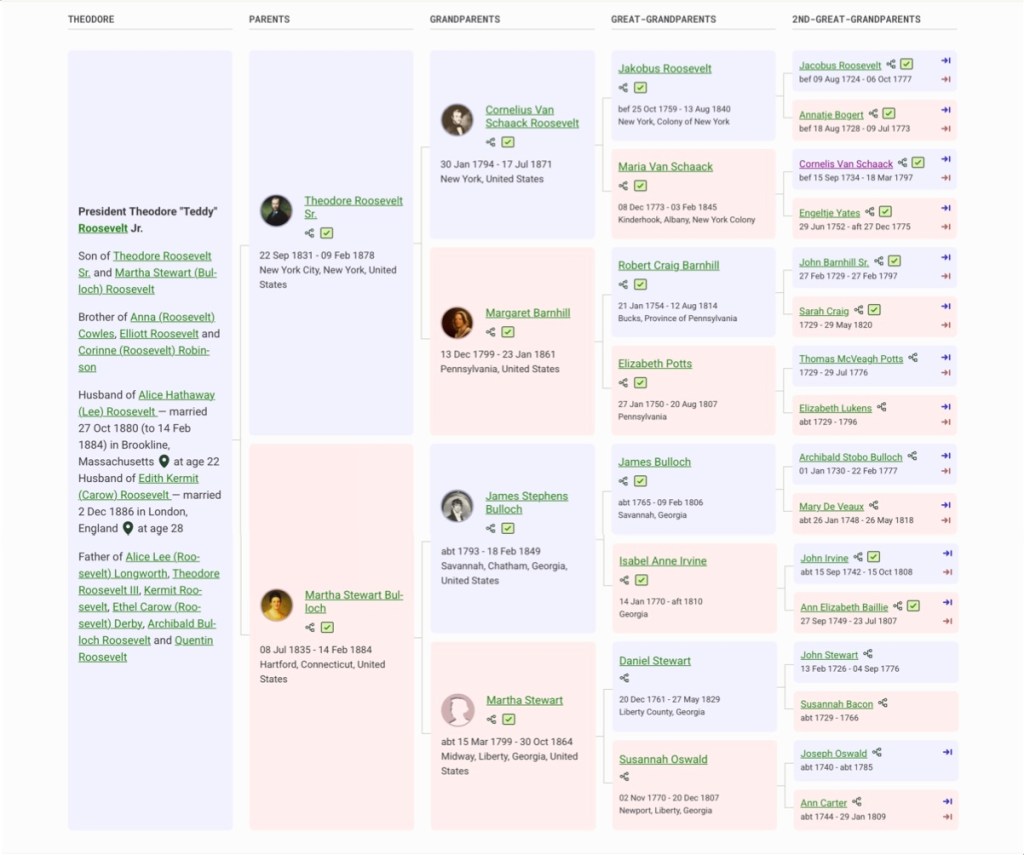

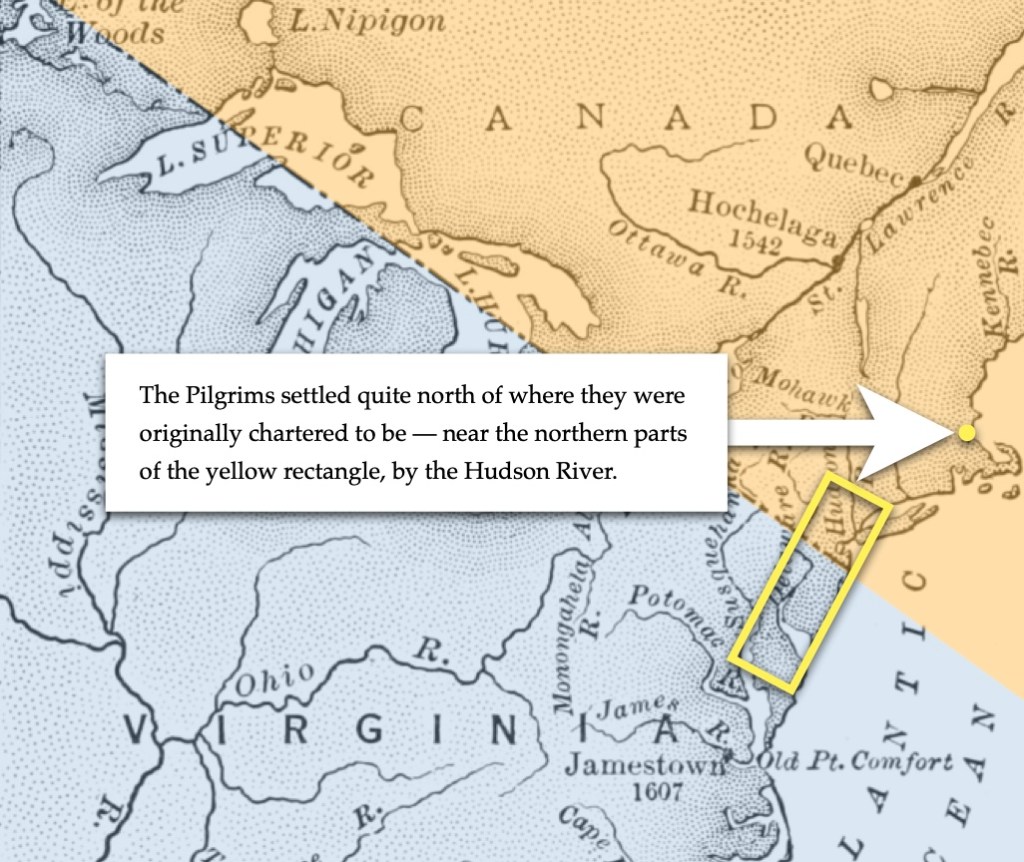

This is Chapter Eight of nine, being the next-to-last chapter of our narrative about the Doty Line. This chapter will introduce a new family line, the Shaw family, whose surname replaces the Doty surname in this part of our family history.

Setting The Stage

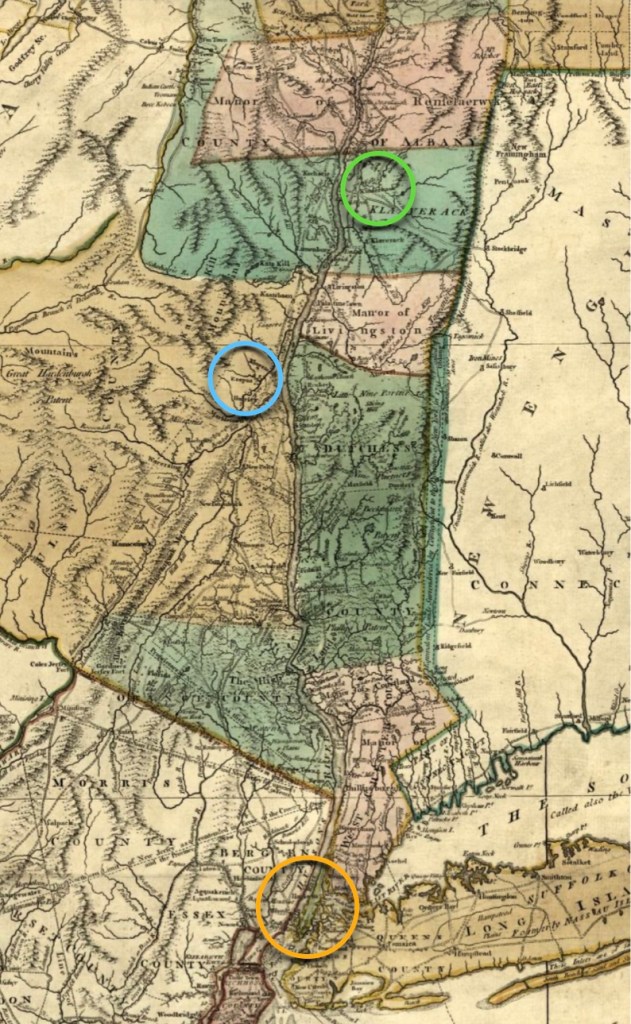

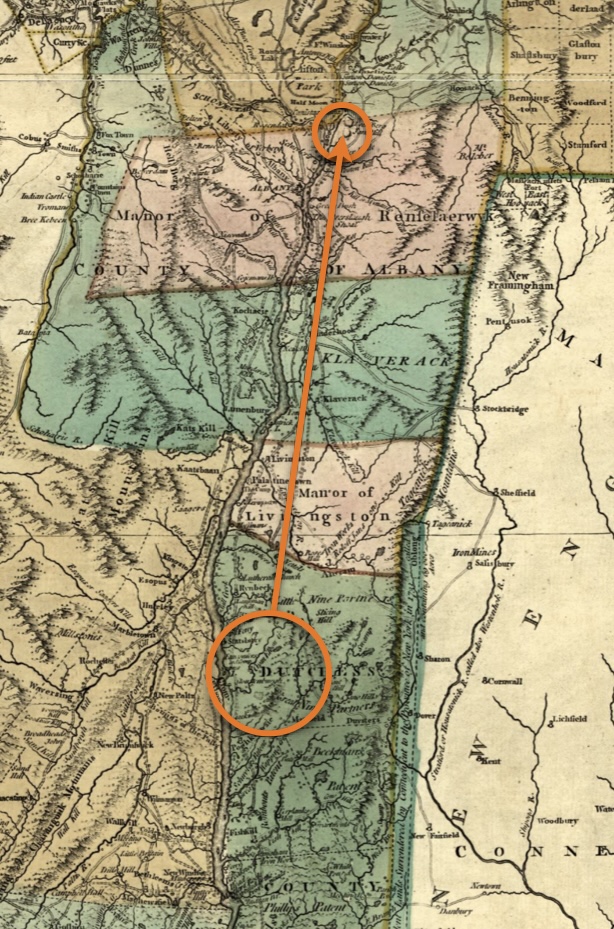

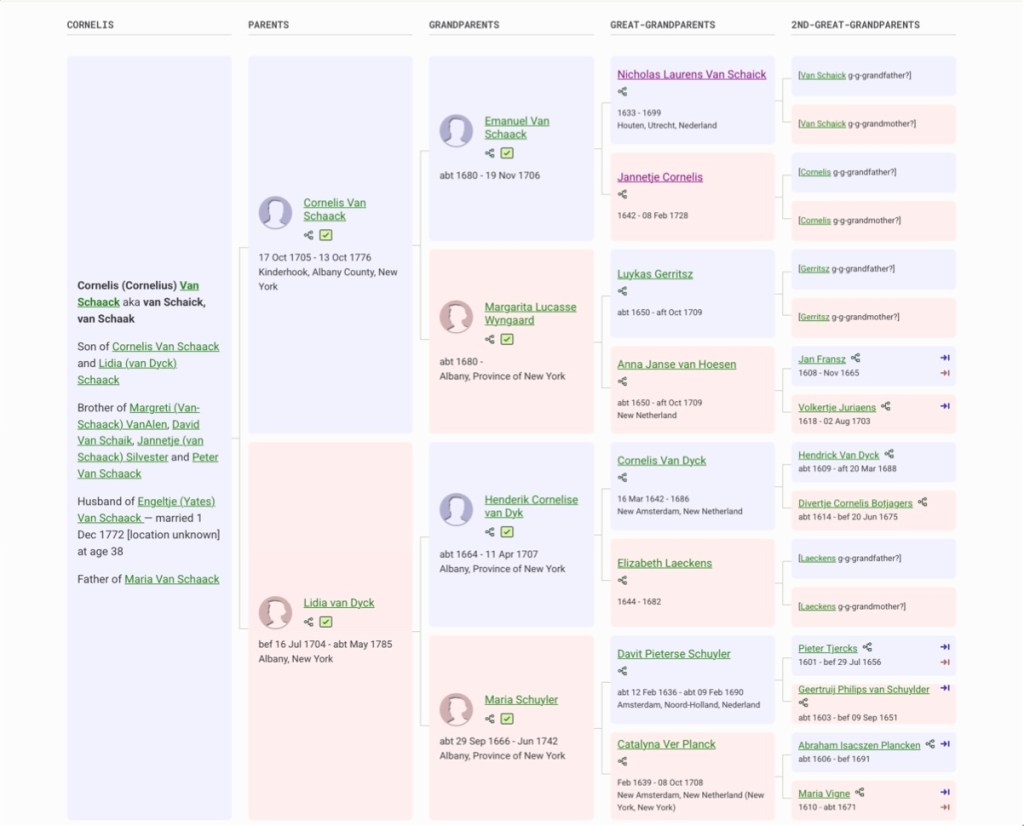

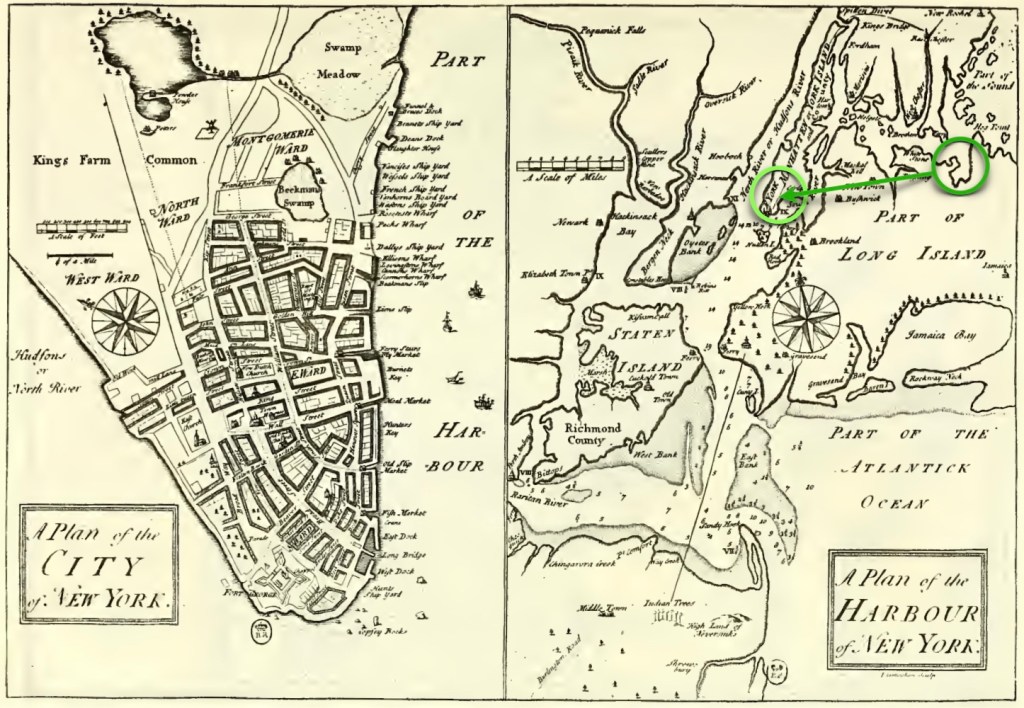

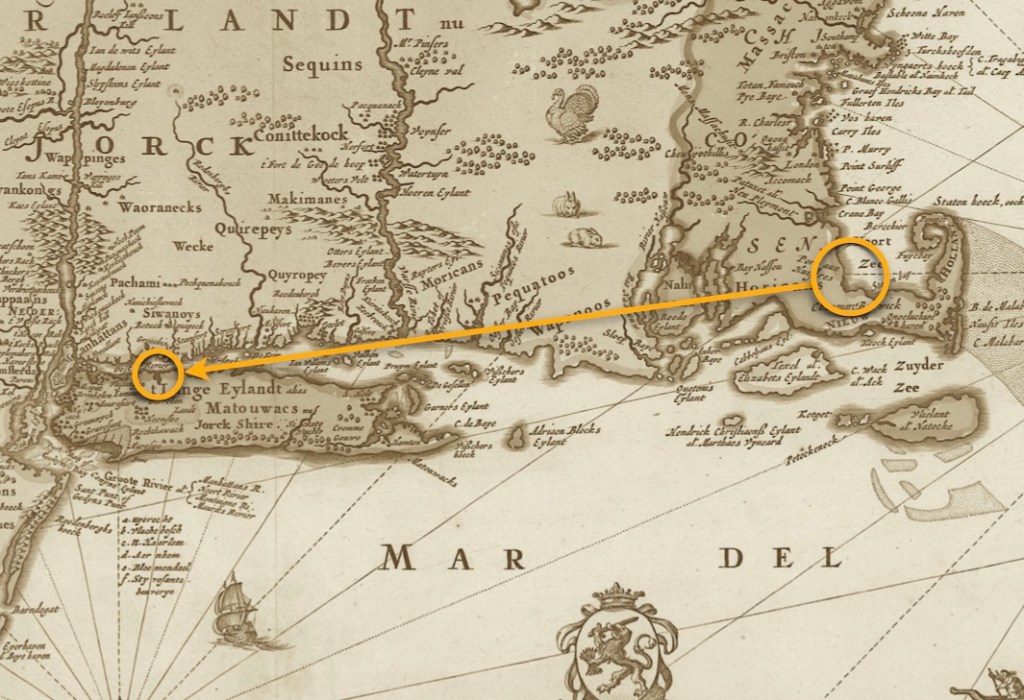

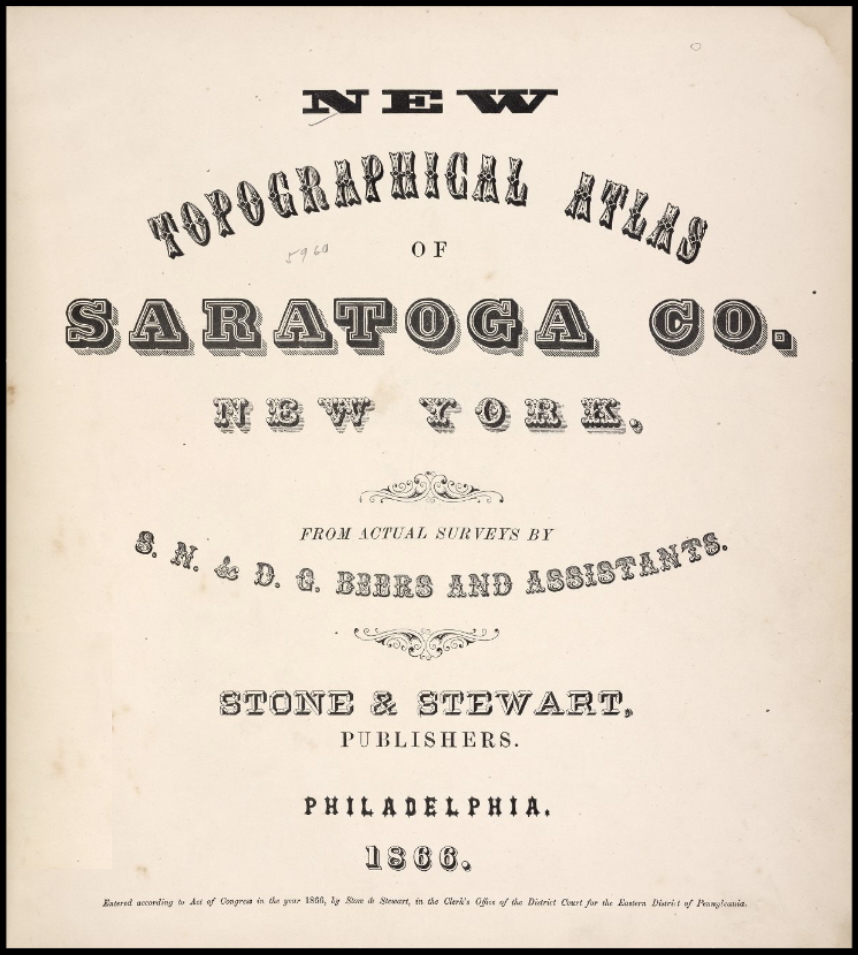

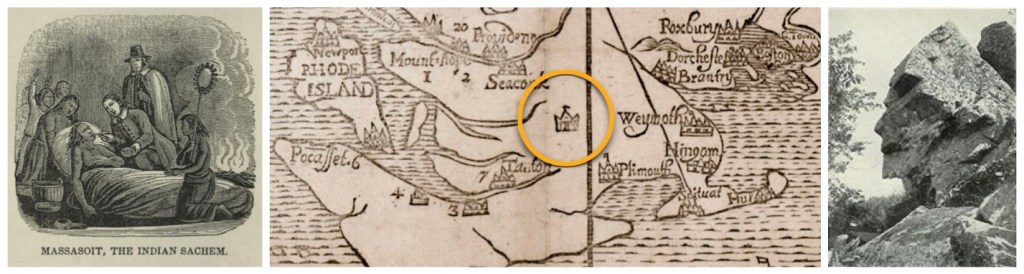

For the first part, the entire history takes place in a relatively small area of the upper Hudson River, at its confluence with the Mohawk River. As you can see in the map below, the town of Cohoes (Falls) is circled in orange. The area circled in yellow covers the district of Schaghticoke, and the towns of Lansingburgh, and Pittstown. Note the town of Troy shown just below Lansingburgh.

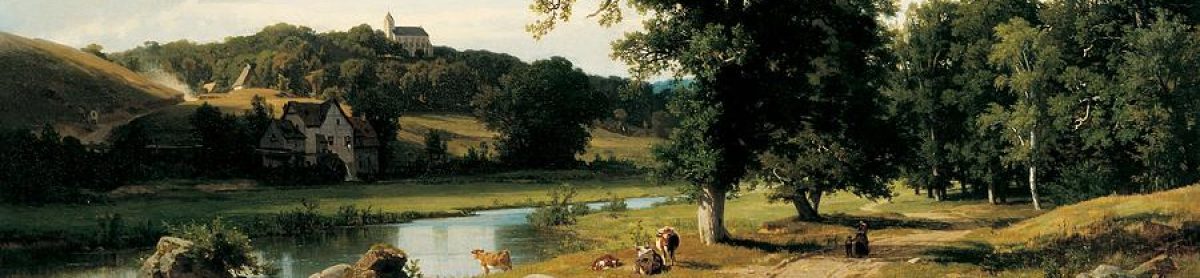

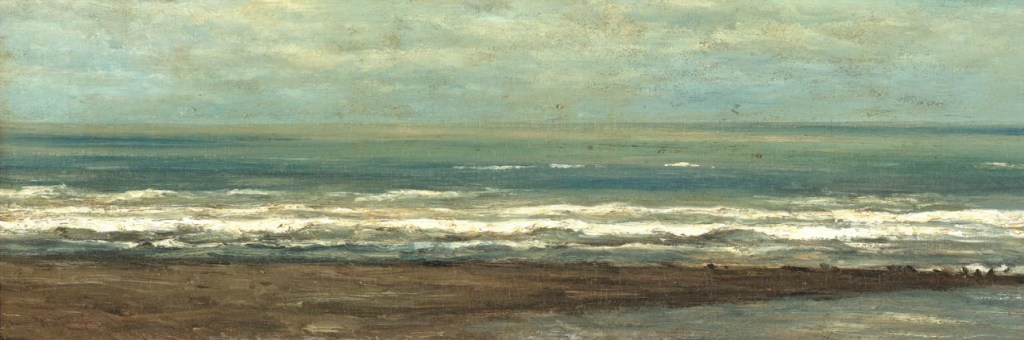

In their era, borders, place names, and populations were always in flux, so we try to feature images which are as accurate as possible to the timeframe. As powerful as maps are for location orientation, we do sometimes come upon an image which helps readers to be grounded in a particular place. One such image is shown below, Troy from Mount Ida (No. 11 of The Hudson River Portfolio).

Various artists/makers, circa 1821–22. (Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art).

This view shows the Hudson River at the border of Lansingburgh.

Look within this artwork and observe that the rain clouds have just cleared away, the late afternoon sunlight is just starting to shine through, it’s very quiet, except for the birds who are starting to call to one another. Two people are making their way along the river road. Maybe we can hear the murmur of their voices?

Imagine that you are standing at this most southern viewpoint in the new town of Lansingburgh, looking toward the south, down the Hudson River. Before you lies the small village of Troy.* In front of you are three islands, located where the Hudson meets the Mohawk. One island is named Van Schaick — which is likely named after one of Lydia Doty’s ancestors who were very early to this area. Behind you, with the breeze to your back, lie the towns of Lansingburgh, Pittstown, and Schaghticoke, where the future of this family unfolds.

Finally, to the right of the three major islands, lies the small town of Cohoes, where the our exploration truly begins.

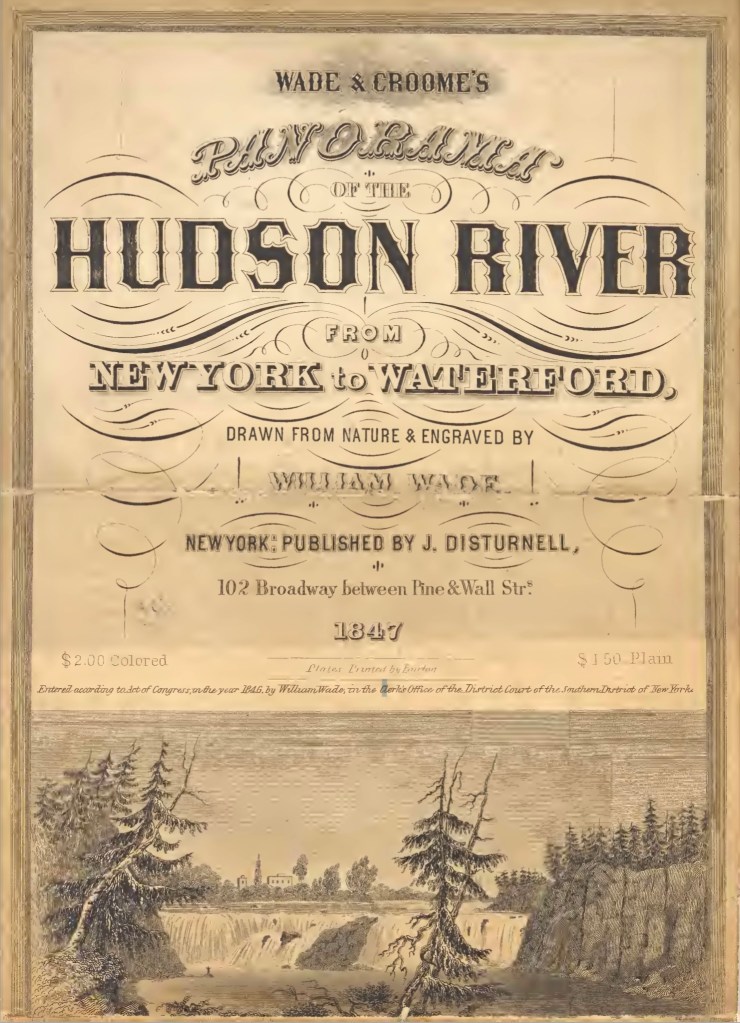

from Wade & Croome’s Panorama of the Hudson River from New York to Waterford,

by Wade, Disturnell, and Croome.

The image above is an open panoramic view from the 1840s, found within a unique souvenir book. It is built in an accordion style, with views that stretch out for 38 continuous hand-colored panels. It features aerial and panoramic views along both shores of the Hudson River, from New York City, on Manhattan Island, up to the Mohawk river junction at the town of Waterford (across the river from the town of Lansingburgh).

Our Comment: This souvenir book literally mirrors the historical movement of our family as it journeys from New Amsterdam / Manhattan, to Lansingburgh.

*We learned about the eventual ascendance of Troy as a metropolitan city; with it eventually overtaking and eclipsing all the other communities in the area in terms of prominence. From Wikipedia, “Through much of the 19th and into the early 20th centuries, Troy was one of the most prosperous cities in the United States. Prior to its rise as an industrial center, it was the transshipment point for meat and vegetables from Vermont and New York, which were sent by the Hudson River to New York City. The trade was vastly increased after the construction of the Erie Canal, with its eastern terminus directly across the Hudson River from Troy at Cohoes in 1825”. (1)

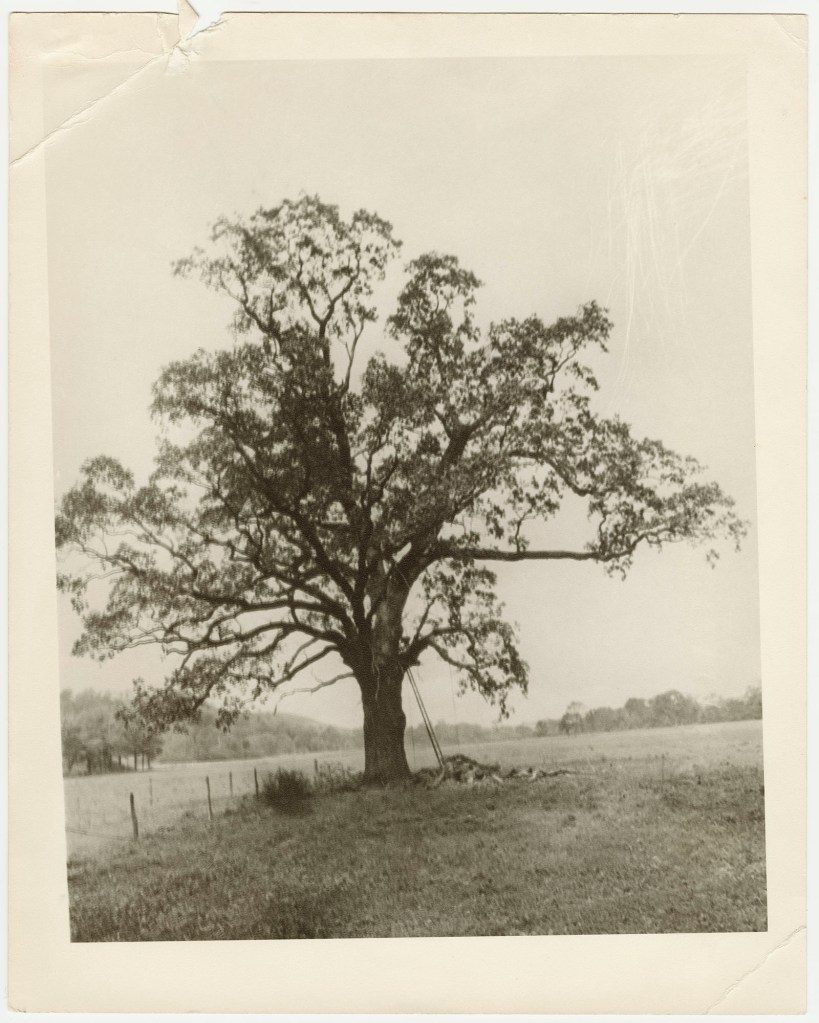

A Tree of Welfare

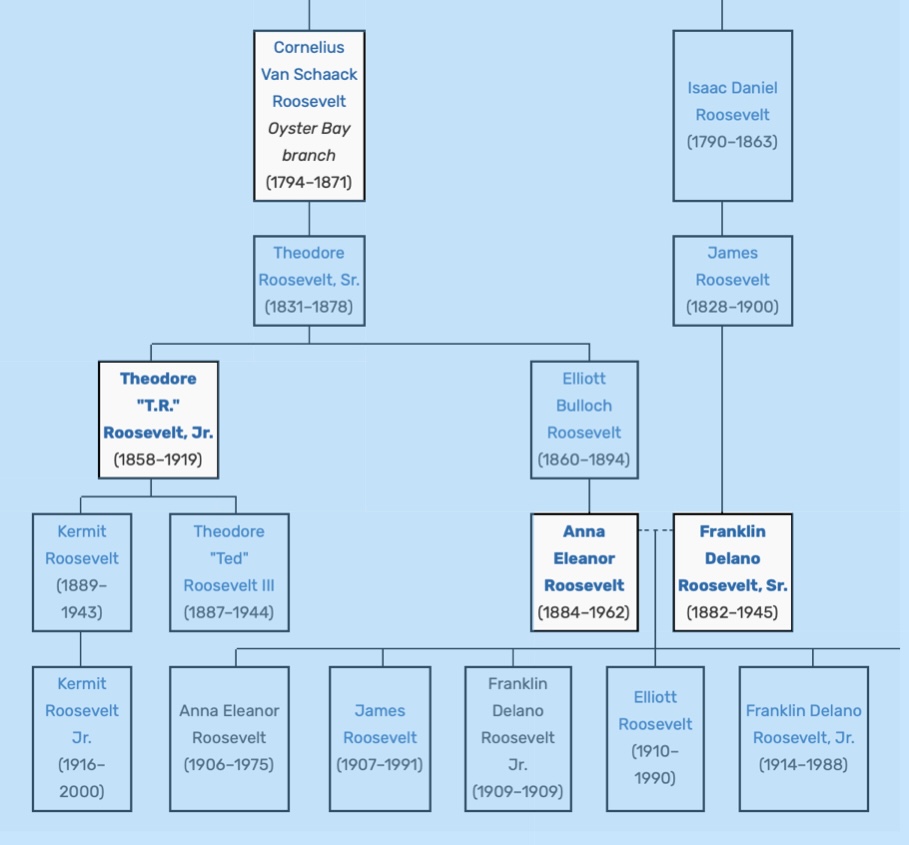

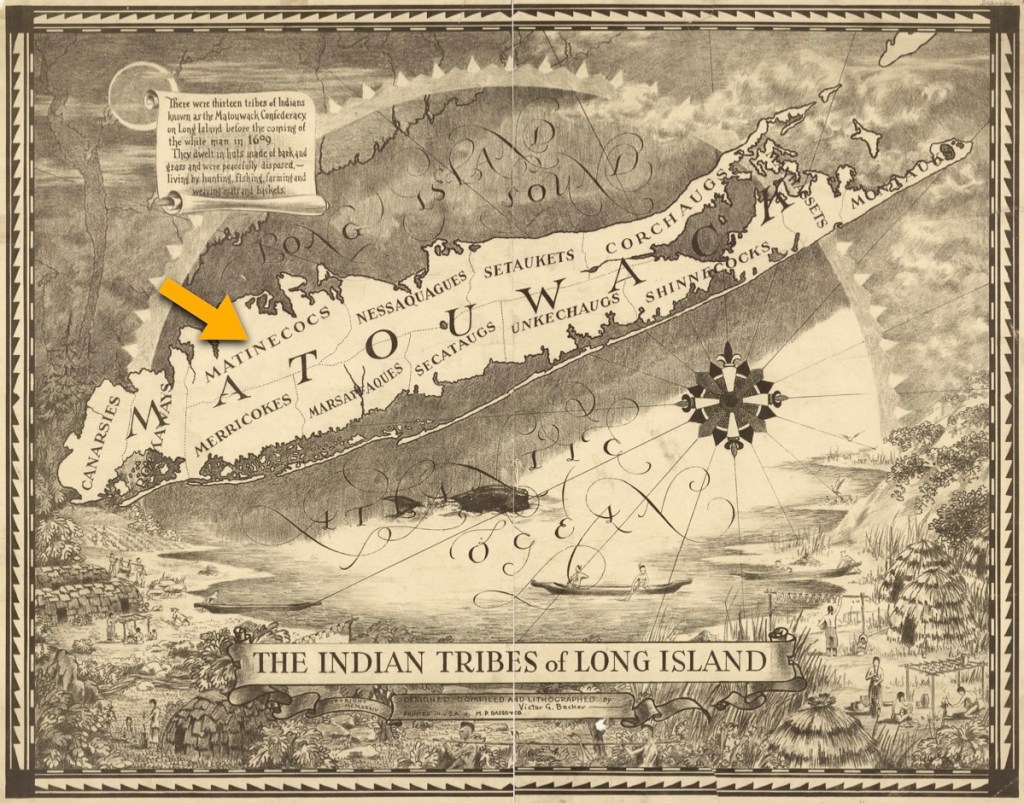

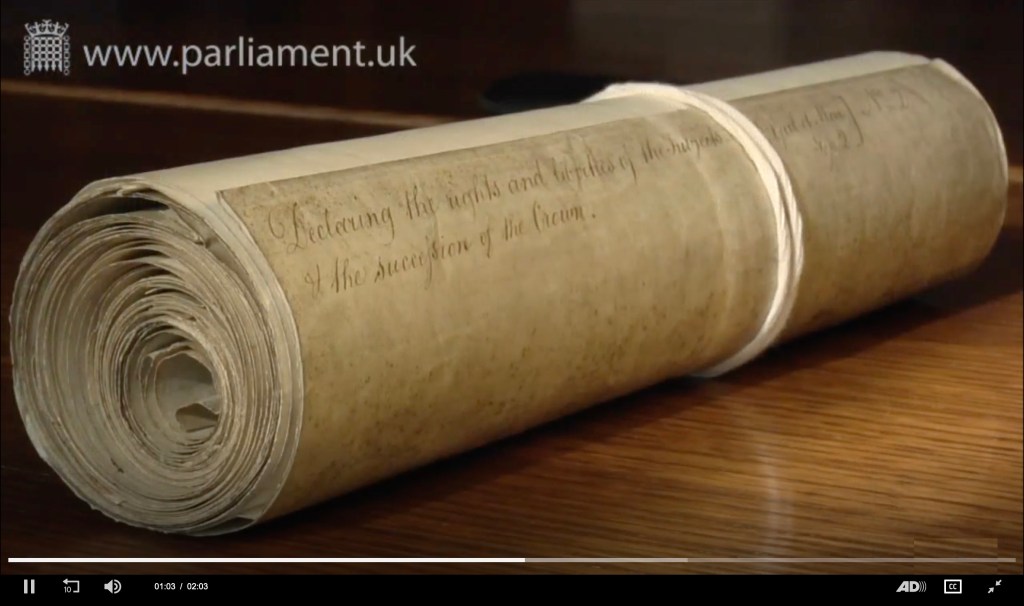

This family eventually lived in several adjacent communities on both sides of the upper Hudson River. This area had earlier been populated first by Native Peoples, who then gave way to the Dutch, and then the British.

“In 1675, Governor Andros, governor of the colony of New York, planted a tree of Welfare near the junction of the Hoosic River and Tomhannock Creek, an area already known as Schaghticoke, “the place where the waters mingle.” This tree symbolized the friendship between the English and the Dutch, and the Schaghticoke Indians. The Native Inhabitants were Mohican refugees from New England welcomed to Schaghticoke [through a treaty] because they agreed to help protect the English from the French and the Iroquois. They stayed until 1754.

Prior to the proclamation of colonial independence, Schaghticoke was part of the colony of New York with most of its citizens governed by the city of Albany, which owned the land they rented.” (Wikipedia)

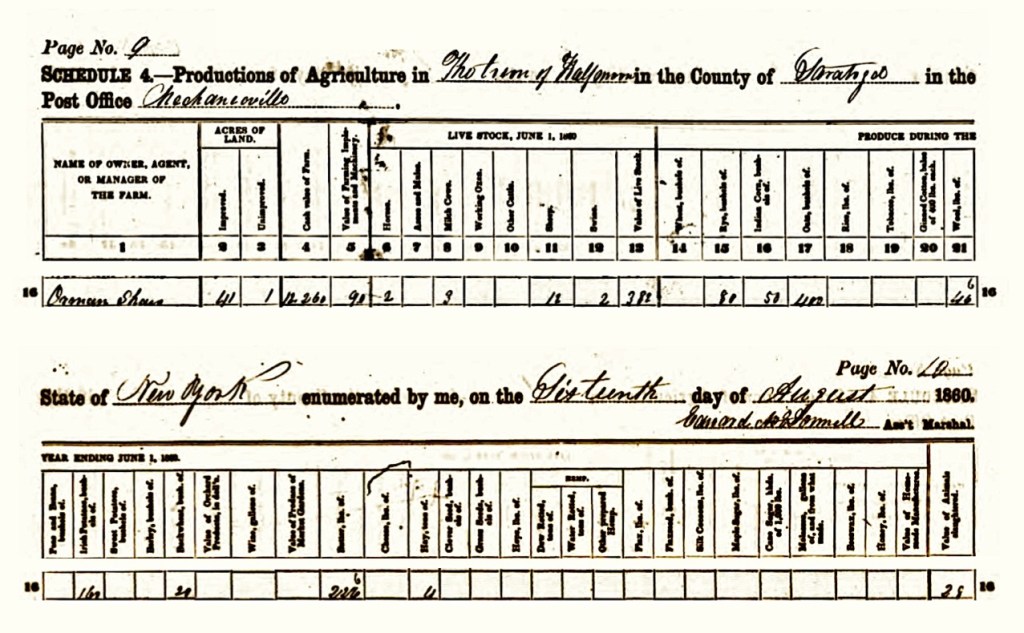

Daniel Shaw, like many of our other ancestors, was a farmer for most of his life. (This was confirmed through his Will). (2)

Getting To Know Daniel Shaw

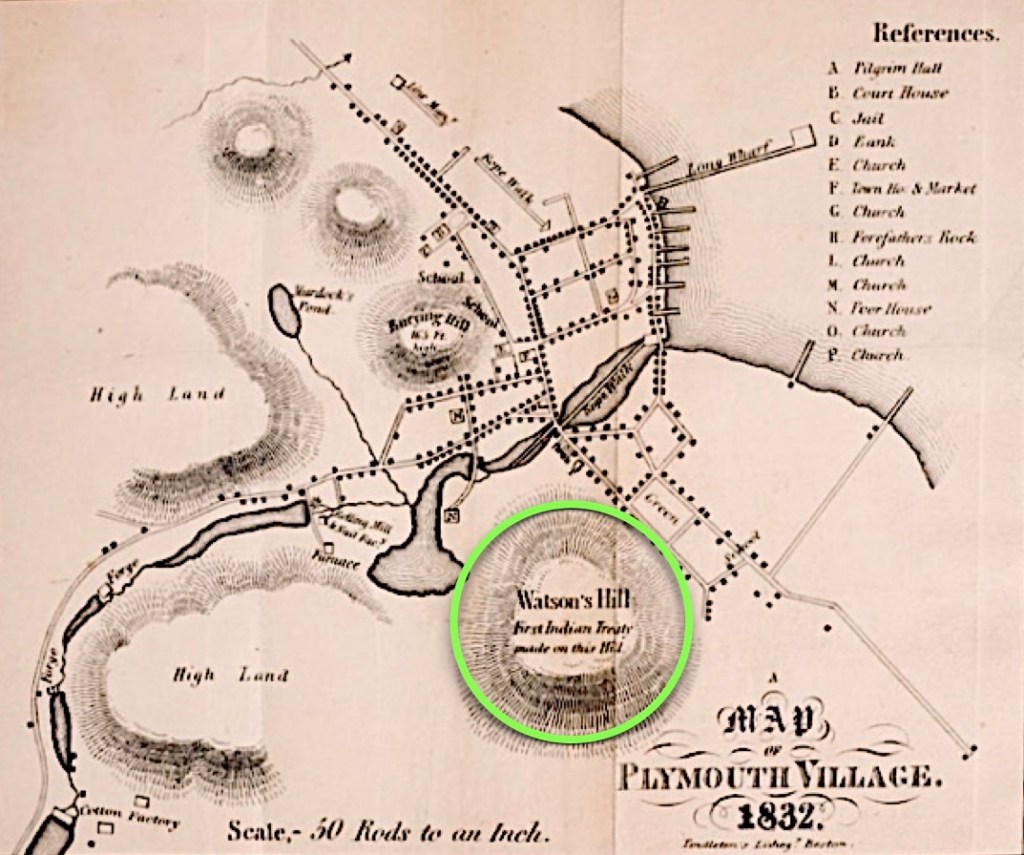

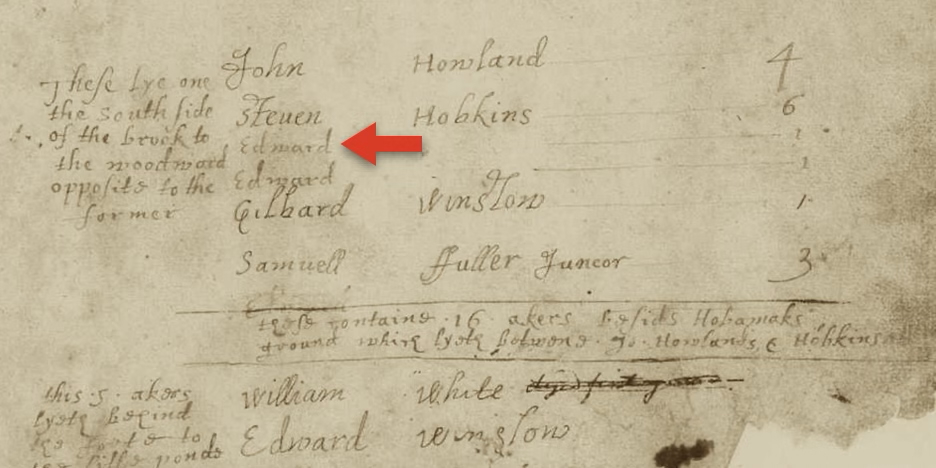

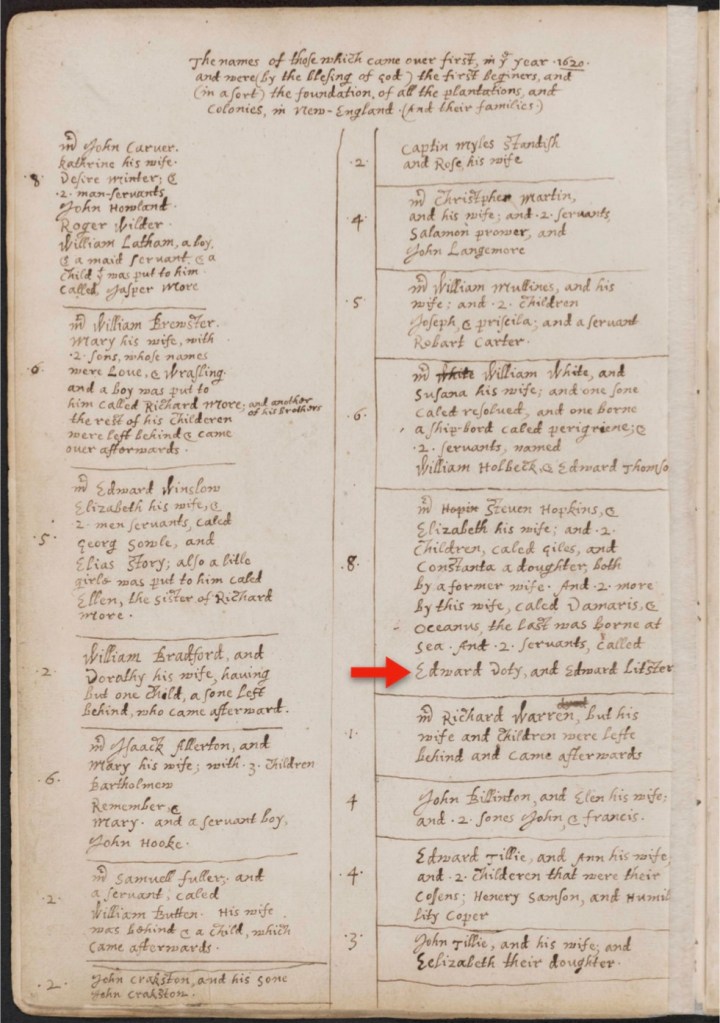

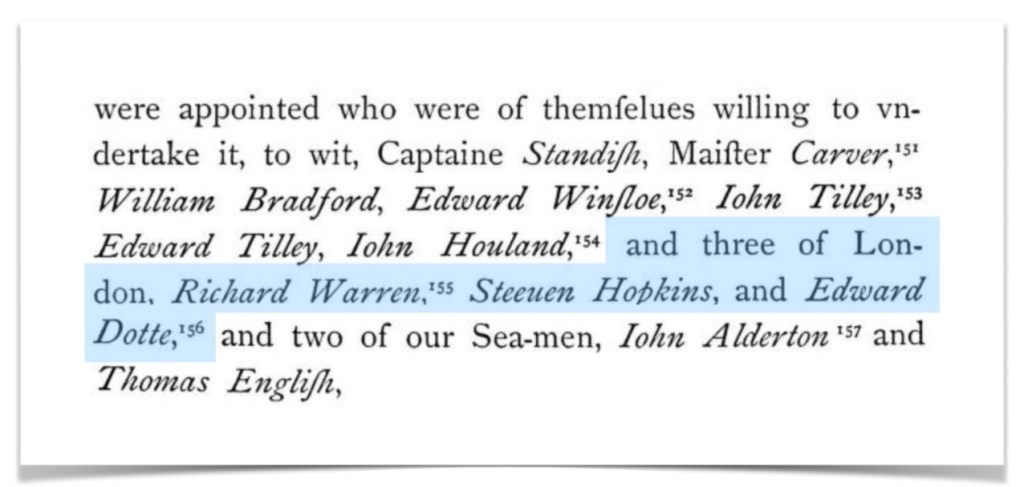

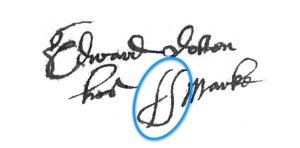

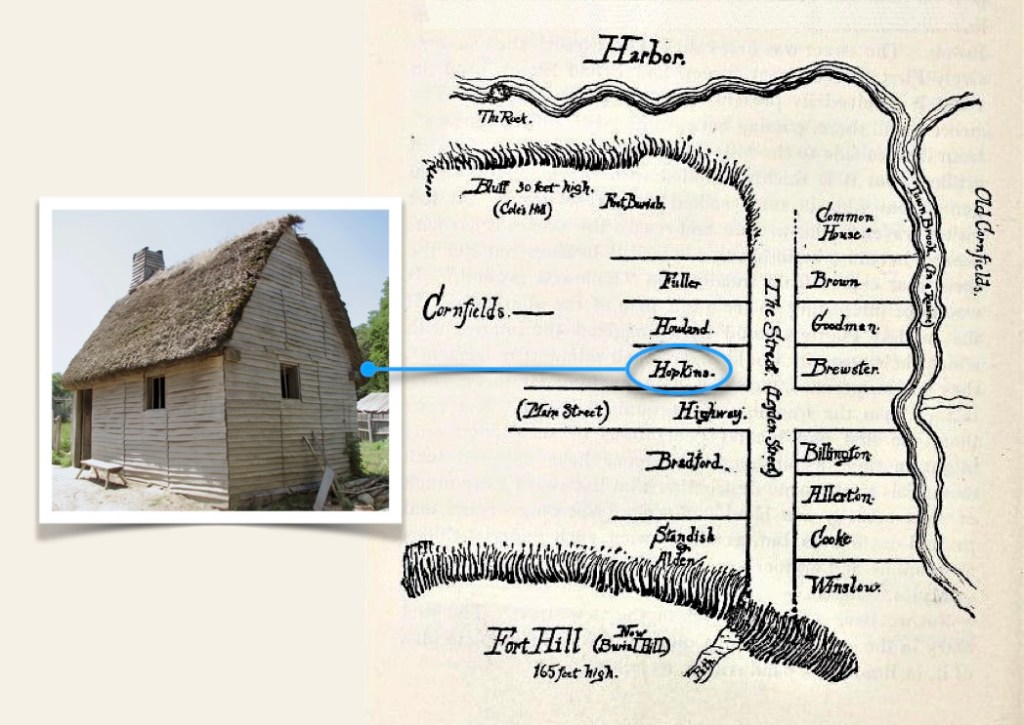

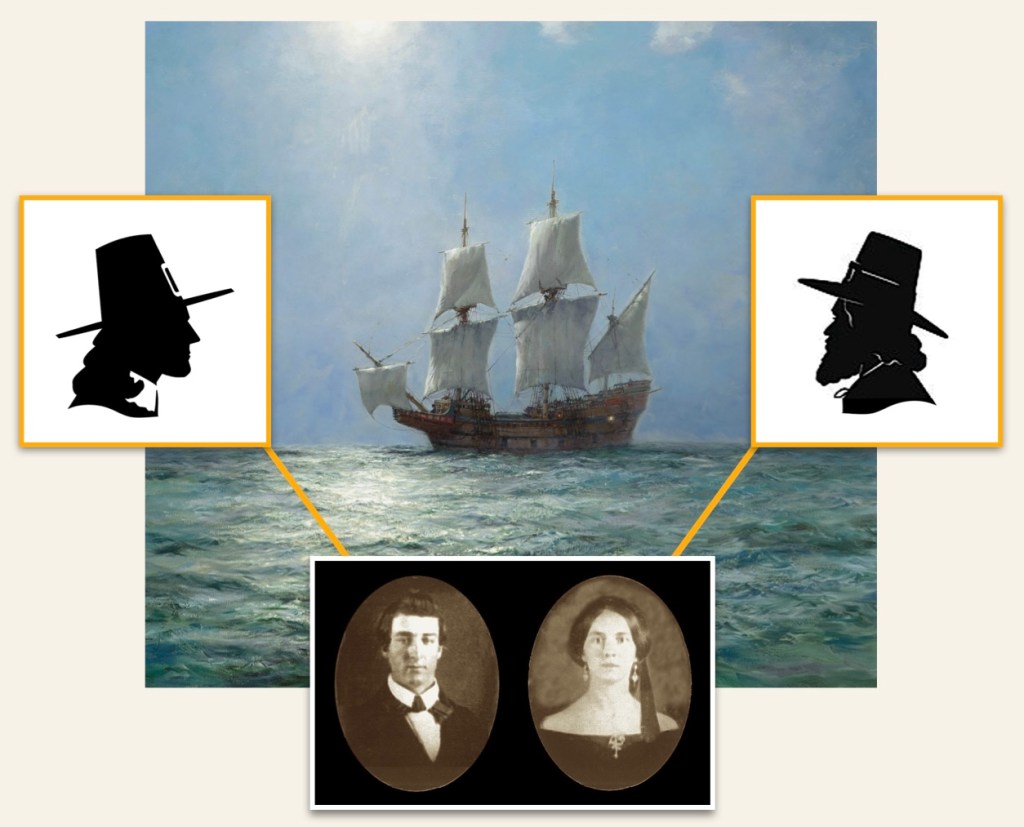

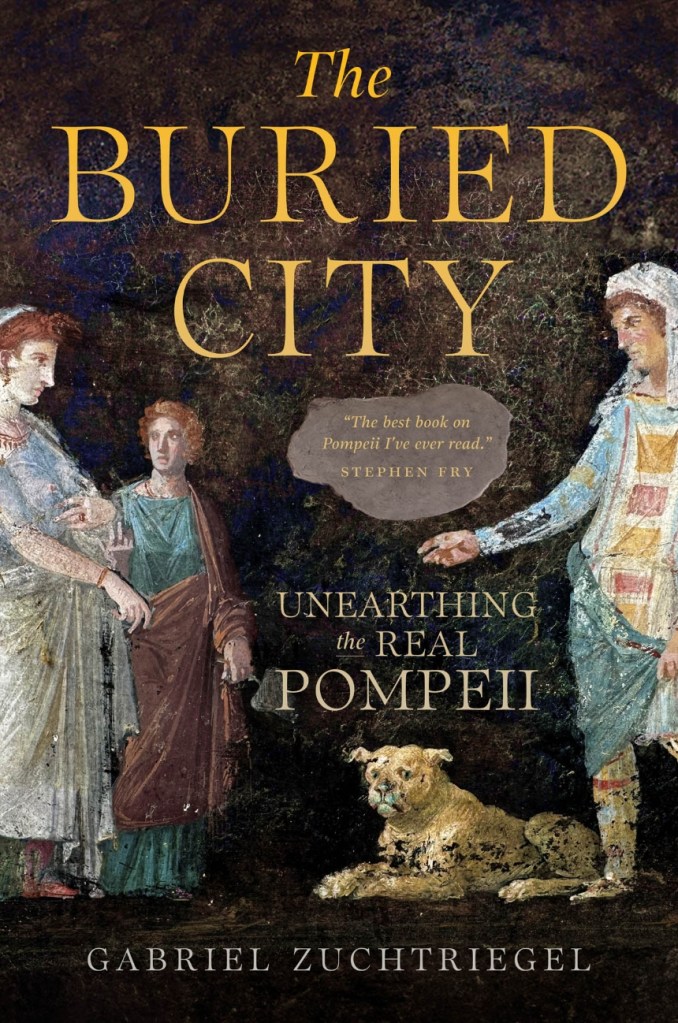

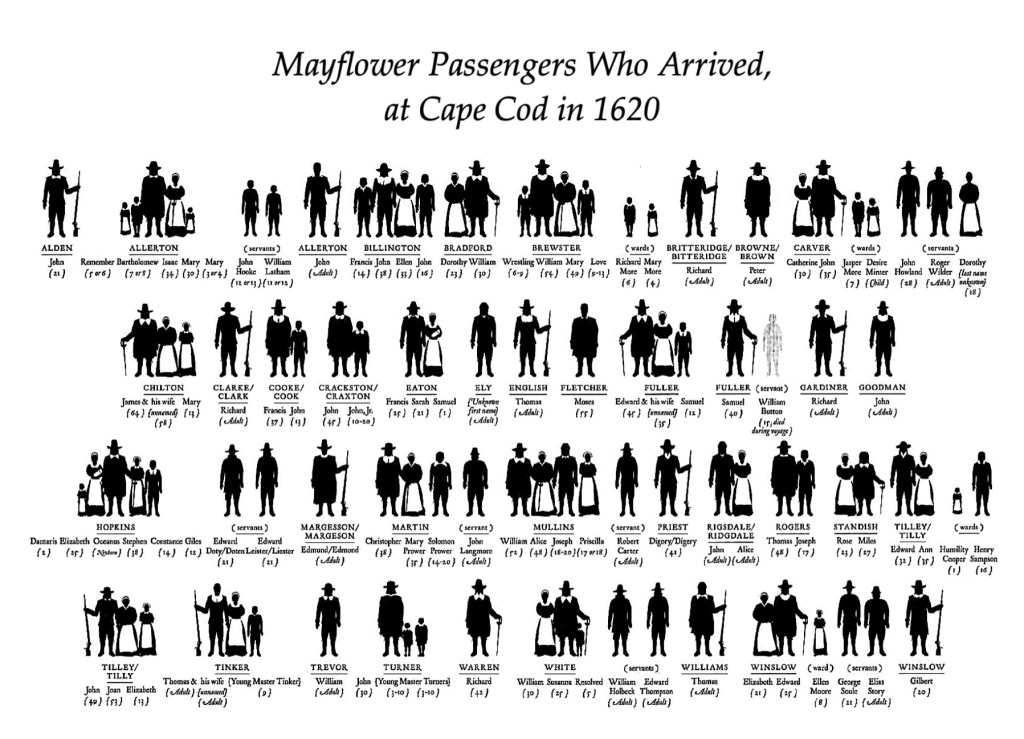

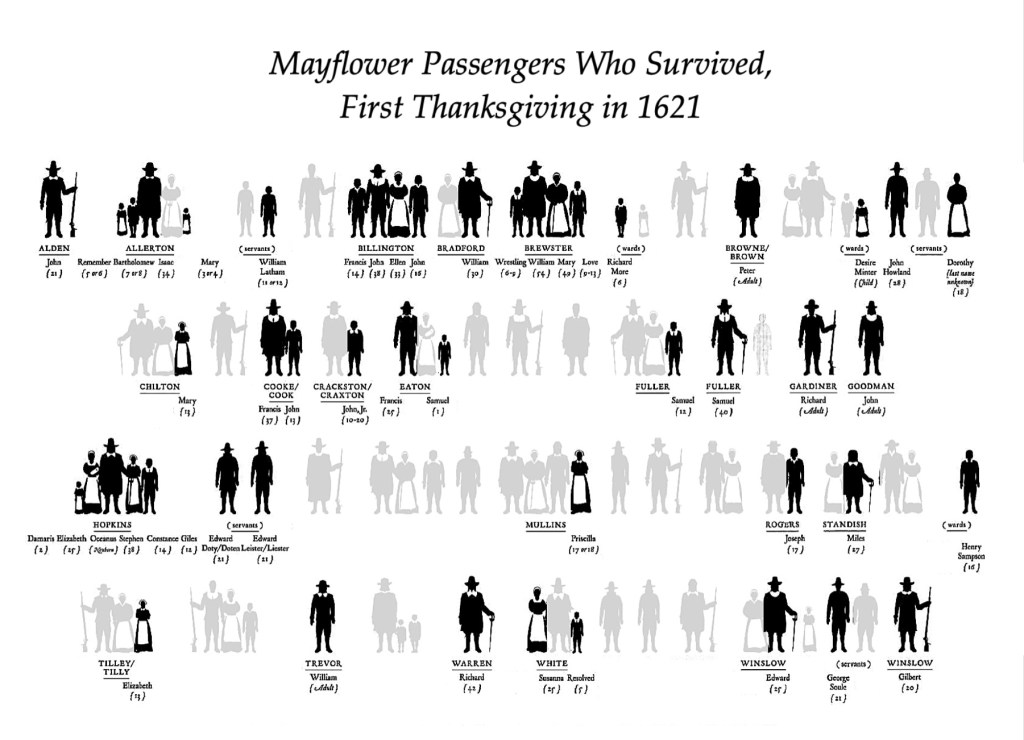

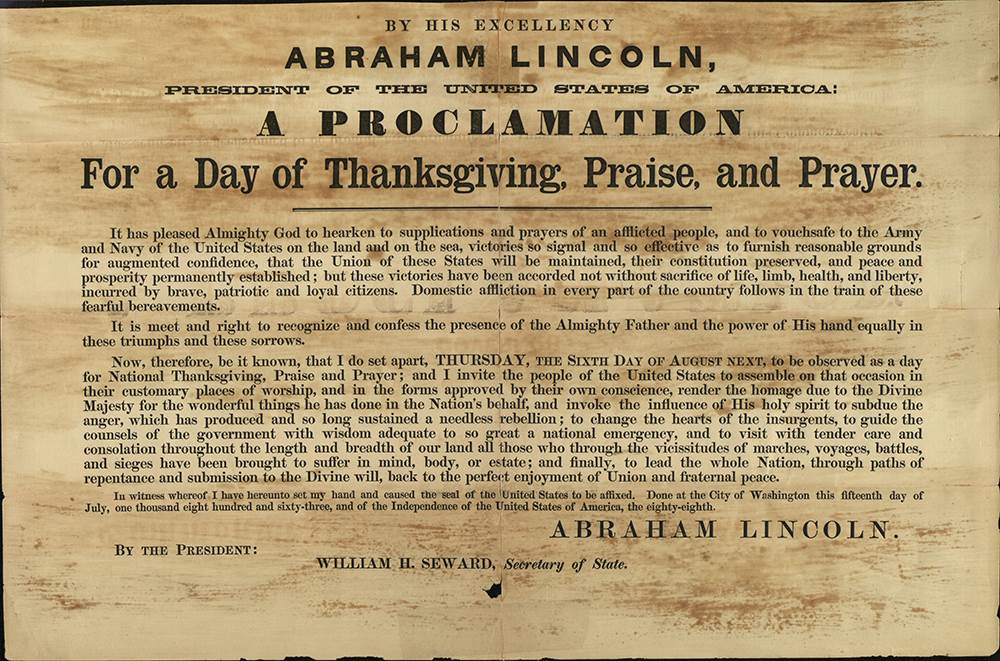

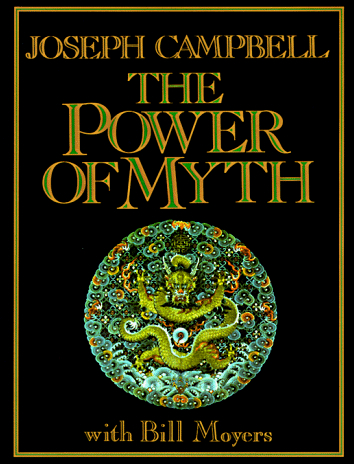

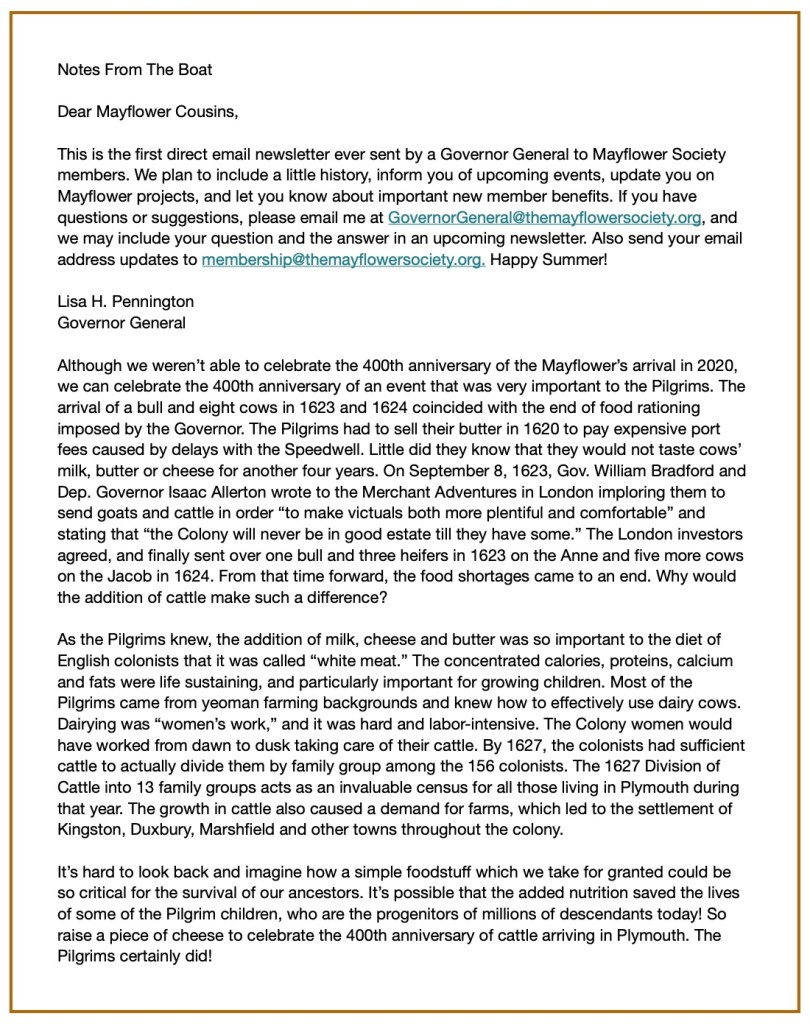

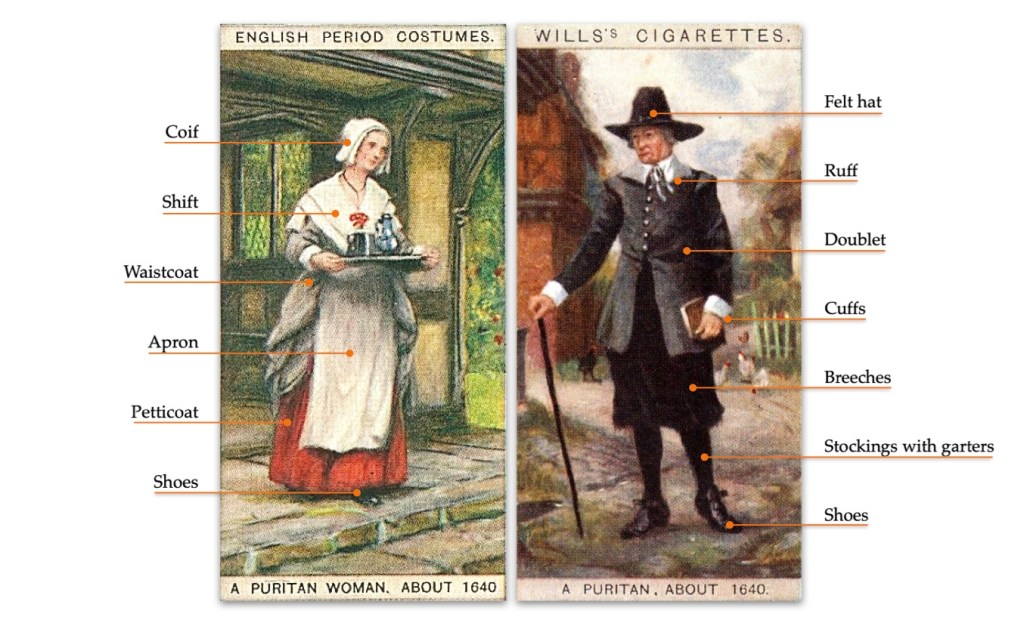

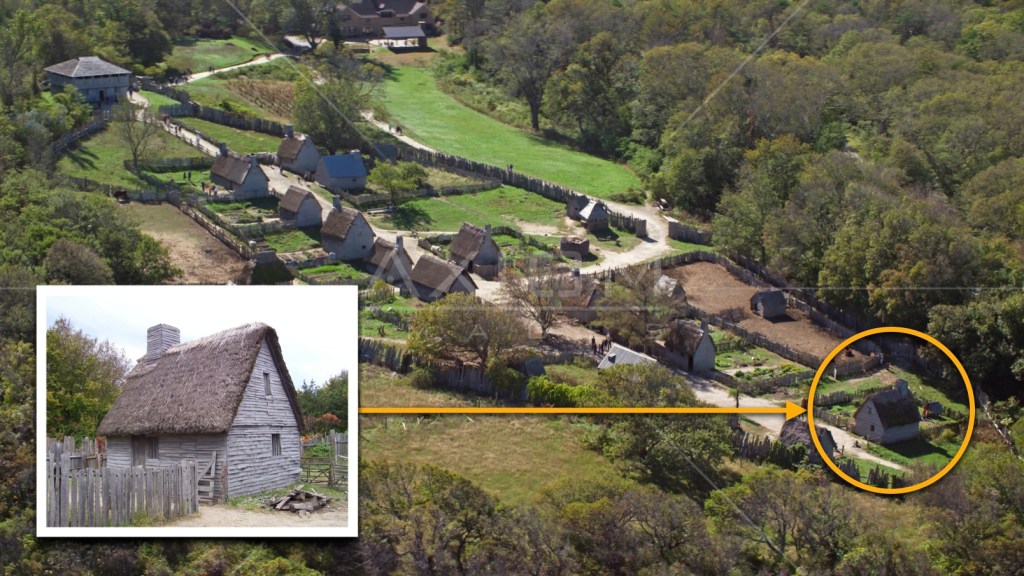

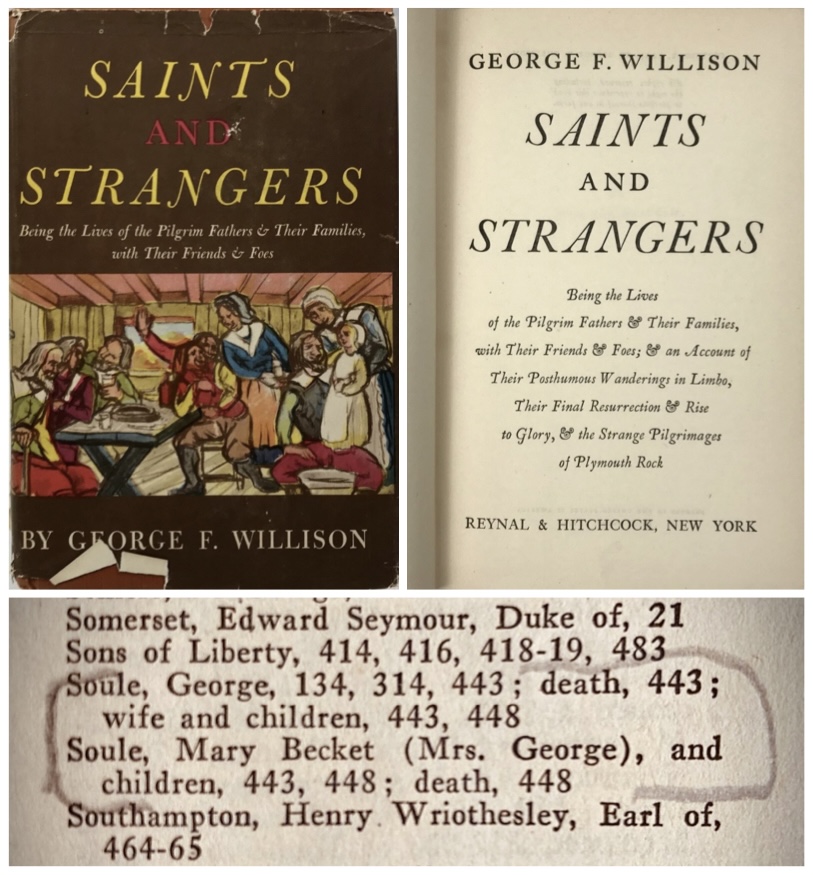

Our research on Daniel Shaw and his birth family is ongoing. At first glance, we thought he may be related to a man named John Shaw who arrived in Plymouth Colony, in 1623 and was very involved in the settling of that place. However, a direct link between the family lines has not yet been found. We learned that another family of Shaws settled in Connecticut, so, as we publish this section of our family blog, we are researching that possible connection. (Updates will be added as we resolve the Shaw family line history).

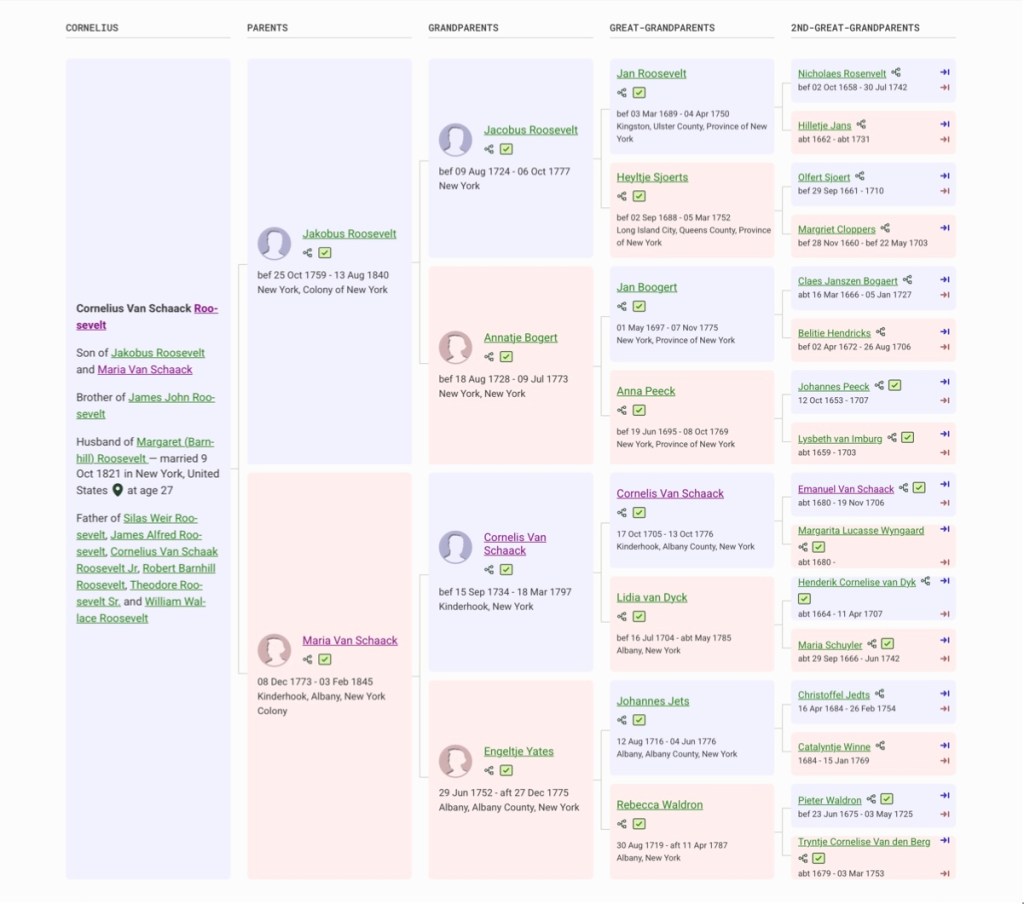

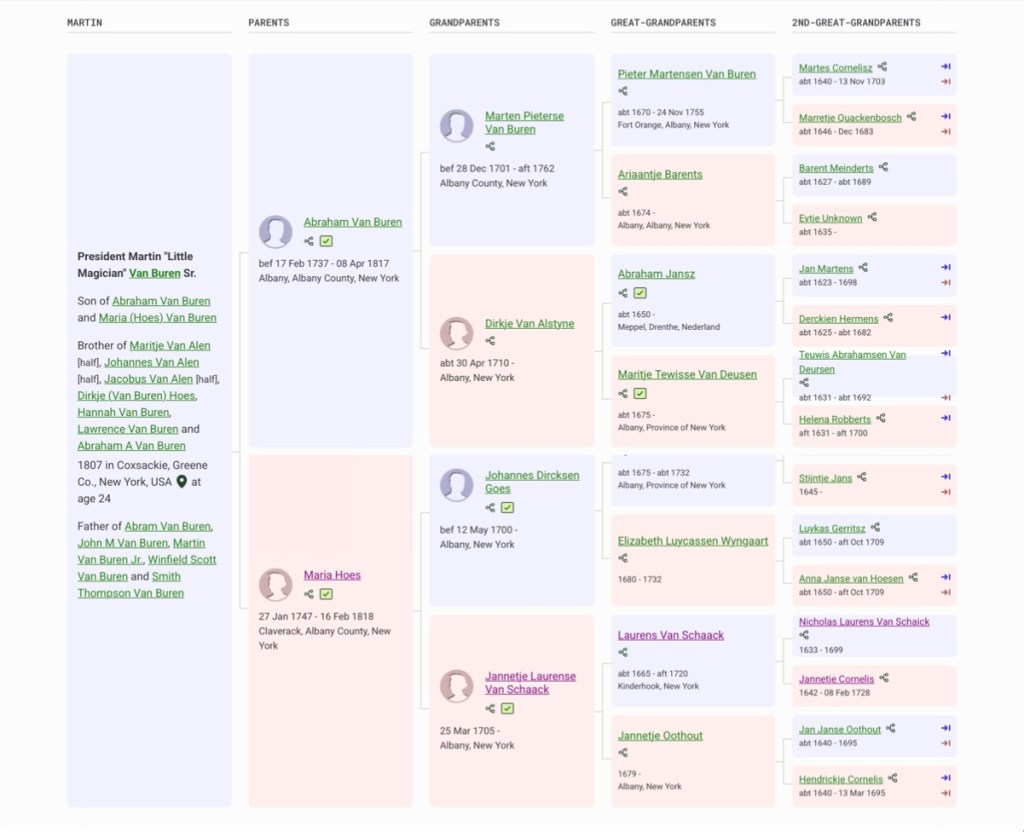

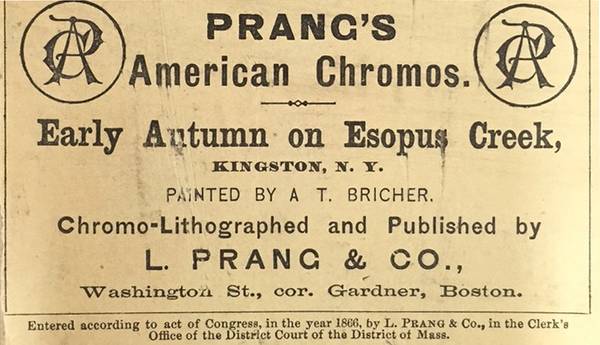

Therefore, this grandfather is a bit enigmatic — due to the fact that not much information about his life before meeting Lydia Doty seems to have surfaced. He was barely mentioned in the Doty-Doten Family in America book by Ethan Allan Doty, (DDFA).

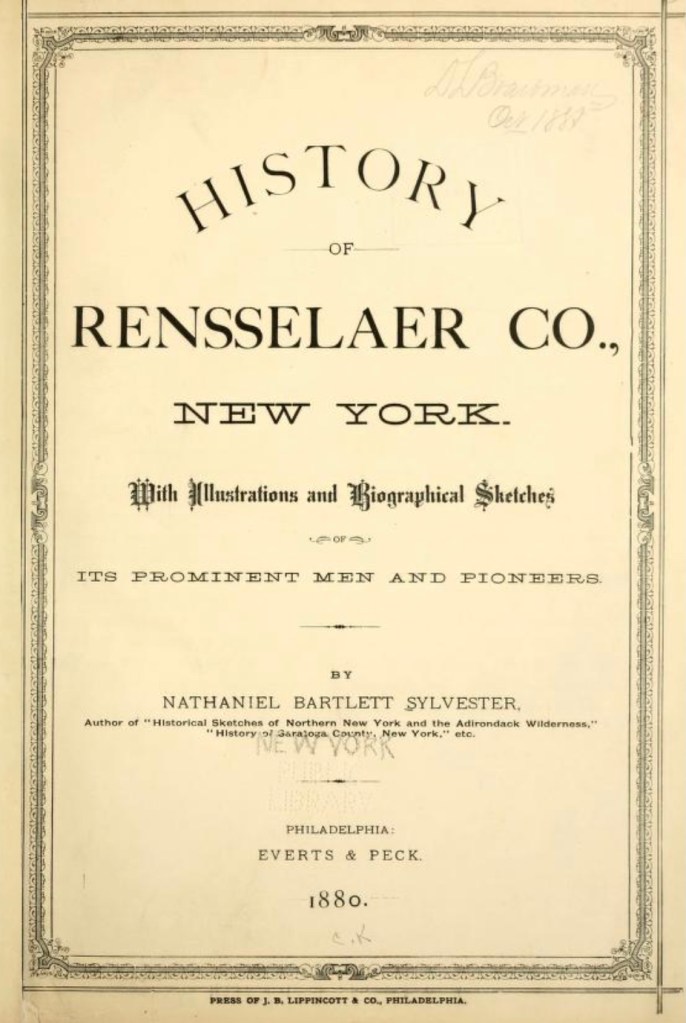

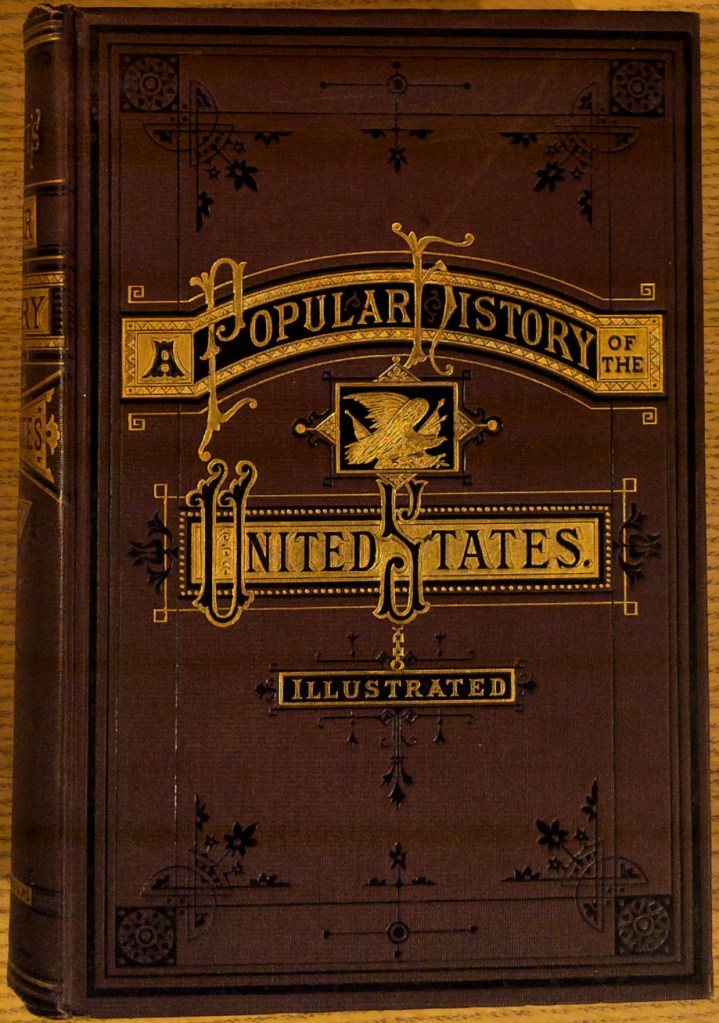

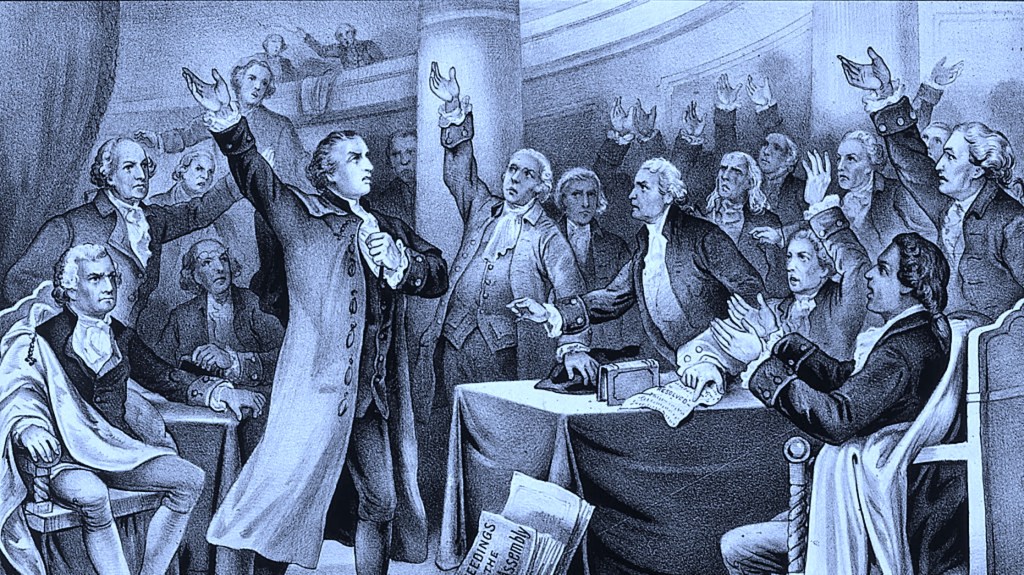

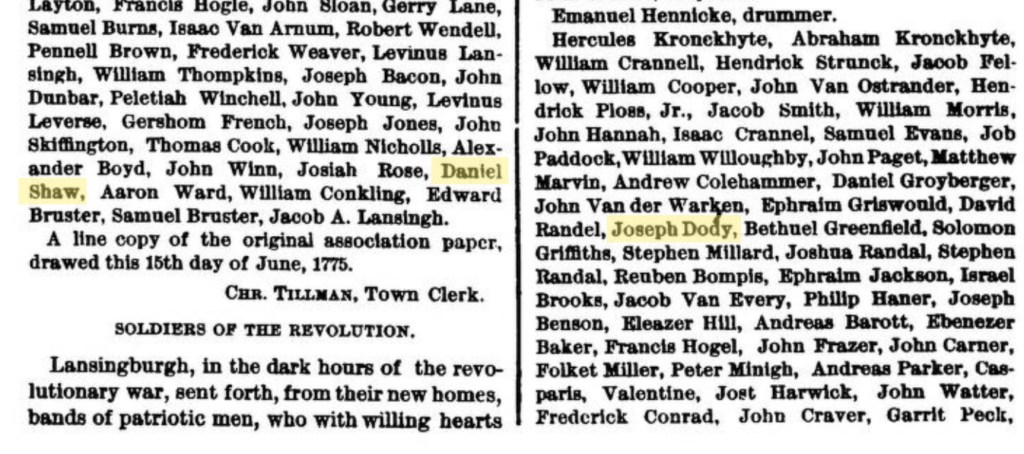

Despite that, in the rather comprehensively titled book, the History of the Seventeen Towns of Rensselaer County, From the Colonization of the Manor of Rensselaerwyck to the Present Time, we first observe Daniel Shaw’s name and the (likely) name of his future father-in-law, Joseph Doty. The context was what was then known as a patriotic pledge, made when American Colonists knew that a war with Great Britain was imminent.

It was a long, patriotic pledge, made on May 22, 1775. The opening paragraph reads: “A general association agreed to and subscribed by the freemen, freeholders and Inhabitants of the town of Lansingburgh and patent of Stone Arabia: Persuaded that the Violation of the rights and liberties of America depends, under God, on the firm opinion of its Inhabitants in a vigorous prosecution of the measures necessary for Its safety,— convinced of the necessity of preventing the anarchy and confusion which attend a dissolution of the power of government, we, the freemen, freeholders and inhabitants of the town of Lansingbugh and patent of Stone Arabia, being greatly alarmed at the avowed design of the British ministry to raise a revenue In America, and shocked by the bloody scenes now enacting In Massachusetts bay government, in the most solemn manner…”

This tells us that he was living in the Lansingburgh area as early as May 1775.

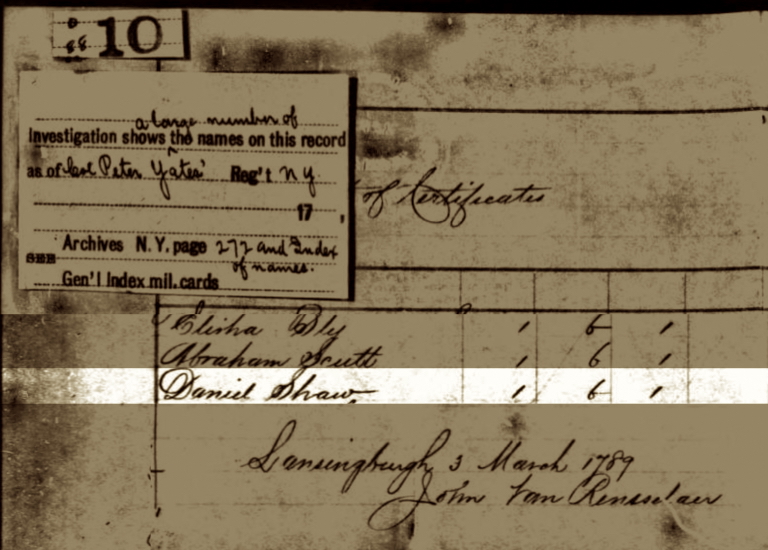

The Albany County area and the local communities were the scenes of many fierce battles during the Revolutionary War. We learned that Daniel had served in the Albany Militia’s Fourteenth Regiment. It appears that years later, in March 1789, he was paid in certificates. The currency of the new United States was not regularized yet and many States still printed their own money. Certificates were issued by the government, which could be used with merchants to pay for goods. (See footnotes).

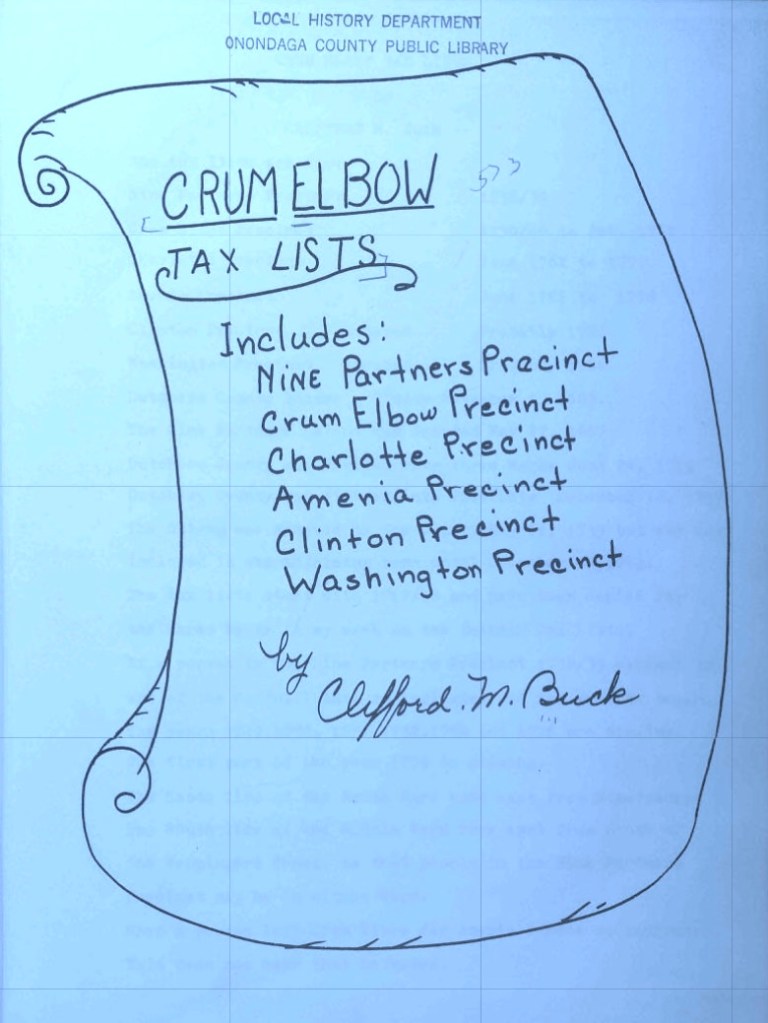

The United States was very new in this era and it was unclear to whom and how property taxes were to be paid. This was still not finalized until many years after The War had ended. We did find tax records from the year 1779. As explained by, the Empire State Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, “Subcommittee on Revolutionary Taxes and have been found to support the War and/or address a request of the Continental Congress. The lists therefore provide evidence of Revolutionary service for those whose names are found on the lists…” In a very young United States, paying the taxes to a government that was not very organized and still evolving… this was seen as a hallmark of patriotic behavior. (3)

New York > Willett´s Regiment of Levies, 1781-1783.

The Colonial Militias of New York

The 14th Albany County Regiment of Militia was a regiment of the New York Militia, and was part of the 2nd Brigade alongside the regiments of Tryon County. (Renamed as Montgomery County in 1784). Militiamen for Albany County were recruited into the 2nd New York Regiment.

Generally speaking, the “Albany County militia was the colonial militia of Albany County, New York. Drawn from the general male population, by law all male inhabitants from 15 to 55 had to be enrolled in militia companies, the later known by the name of their commanders. By the 1700s, the militia of the Province of New York was organized by county and officers were appointed by the royal government. By the early phases of the American Revolutionary War the county’s militia had grown into seventeen regiments.” We learned that Lydia Doty’s brothers Peter, Ormond, and Jacob Doty, were also part of this regiment.

As they were allied with the 2nd New York Regiment, this “regiment would see action in the Invasion of Canada (1775), the Battle of Valcour Island (1776), the Battles of Saratoga (1777), the Battle of Monmouth (1778), the Sullivan Expedition (1779), and the Battle of Yorktown (1781). The regiment would be furloughed, June 2, 1783, at Newburgh, New York.” (Fandom AR Wiki, and Wikipedia) We have another family line living in this exact same area during that time, who also participated in the Battles of Saratoga. Either family or both, may have also participated in The Battle of Klock’s Field, and The Battle of Oriskany. (See The Devoe Line, A Narrative — Five).

Observation 1: It is important to note that these men certainly did not participate in all of these battles. (We know this because they were paying property taxes in March and October 1779). We can credibly believe that The Battles of Saratoga in 1777, is an event which they fought in, because it took place right in their back yard. Other than that, they may have been called up periodically for campaigns.

Observation 2: Daniel Shaw’s friendship with (and awareness of) the Doty brothers, could have led to his meeting their sister, Lydia Doty. (4)

(Image courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library at Yale University).

The Doty Surname Gives Way to Shaw

For this section, unless noted otherwise, all events took place in Albany County, New York State. Of note: Albany County was reformed to be Rensselaer County, in 1791. So, before 1791 > Albany County, and after 1791 > Rensselaer County. Furthermore, when a county name changes, such as in a record for a marriage or a death, we have noted this.

We believe that in about 1783, Daniel Shaw, married Lydia Doty (likely) in Lansingburgh. He was born about 1760 in (unknown location) – died August 13, 1842, in Lansingburgh, Rensselaer, New York. Lydia Doty was born in December 1769 in Lansingburgh, (then Albany County), New York – died November 2, 1830, in Schaghticoke, Rensselaer, New York.

Daniel was about 9 to 10 years older than Lydia, and she was only about 14 to 15 when she married him. Even though we do not know the exact death date for Lydia’s mother Giesje ‘Lucretia’ Doty, we believe that Lydia was very young when her mother died. During this time, the American Revolution was raging all around her. (We speculate that she may have been cared for by an older sister, but we do not have evidence for this. Even though we have seen similar circumstances in other family lines). The truth is, we do not know who actually cared for her, or her younger sister Nancy.

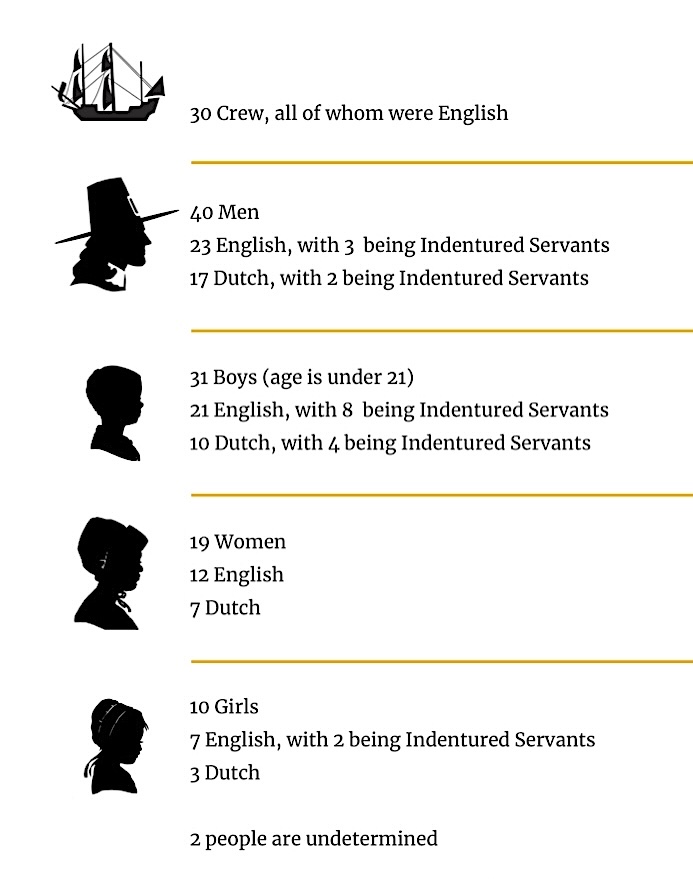

Together Daniel and Lydia had 10 children, who are listed below. In the 1790 Census, the family is shown as living in Pittstown, Albany County. Therefore, we believe that the first five children: Lucretia, Daniel Jr., Nancy, William, and Orman, were born there.

- Lucretia (Shaw) Preston. She was born about 1784 – died after 1865 in Verona, Oneida County. She married James Preston, date unknown.

- Daniel Shaw, Jr. He was born about 1786 – died January 17, 1857 in Greenwich, Washington County.

- Nancy (Shaw) Stover. She was born April 11, 1788 – died March 21, 1872 in Somers, Kenosha County, Wisconsin. She married Joseph Stover. We noted that of all these siblings, she was the only one to relocate outside of New York State.

- William Shaw. He was born September 11, 1789 – died May 16, 1876 in Ulster County, New York. He married two times, with both marriages being in New York. First, to Hannah Burhans on July 25, 1812 in New York; second, to Eliza Bonestell on February 7, 1856 in Kingston, Ulster County. Please see the footnotes for an obituary about William’s life.

- Orman Shaw. He was born on March 3, 1790 – died November 24, 1867 in Halfmoon, Saratoga County. About 1811, he married Elizabeth (last name unknown).

We are descended from Orman and his wife Elizabeth.

The next five children: Henry, Soloman, John, Elizabeth, and Hiram, were likely born in the Schaghticoke District, (now) Renssaelar County. This was located just slightly to the west, right next to Pittstown. It could also be that the family may have already been living in Lansingburgh. It was technically a separate municipality from the Schaghticoke District. (Who knows exactly after more than 2oo years of various record keepers?)

- Henry Shaw. He was born 1796 — died (date unknown). He is noted as being the 1842 executor for his father Daniel Shaw’s Will.

- Solomon Shaw. He was born 1797 — died 1863.

- John Shaw. He was born 1799 — died August 1859 in Cohoes. He married Mary Elizabeth Hutchins about 1827.

- Elizabeth (Shaw) Baninger. She was born 1802 — death date unknown. She married (first name unknown) Baninger.

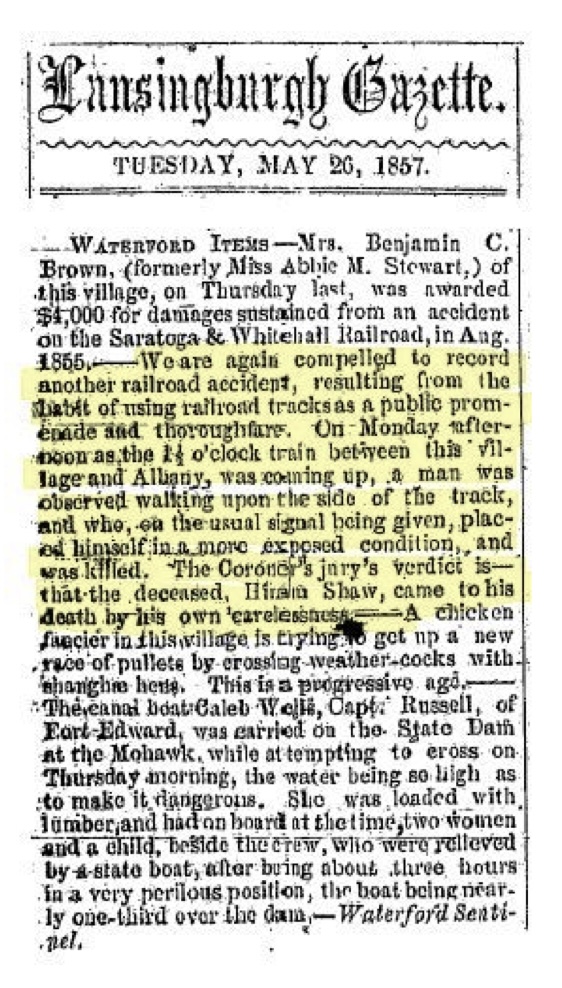

- Hiram Shaw. He was born 1804 — died May 25, 1857, Waterford, Saratoga County. He married Jane A. Patten about 1823. (He died a tragic death, please see the footnotes). (5)

Perhaps He Was A Prudent Man?

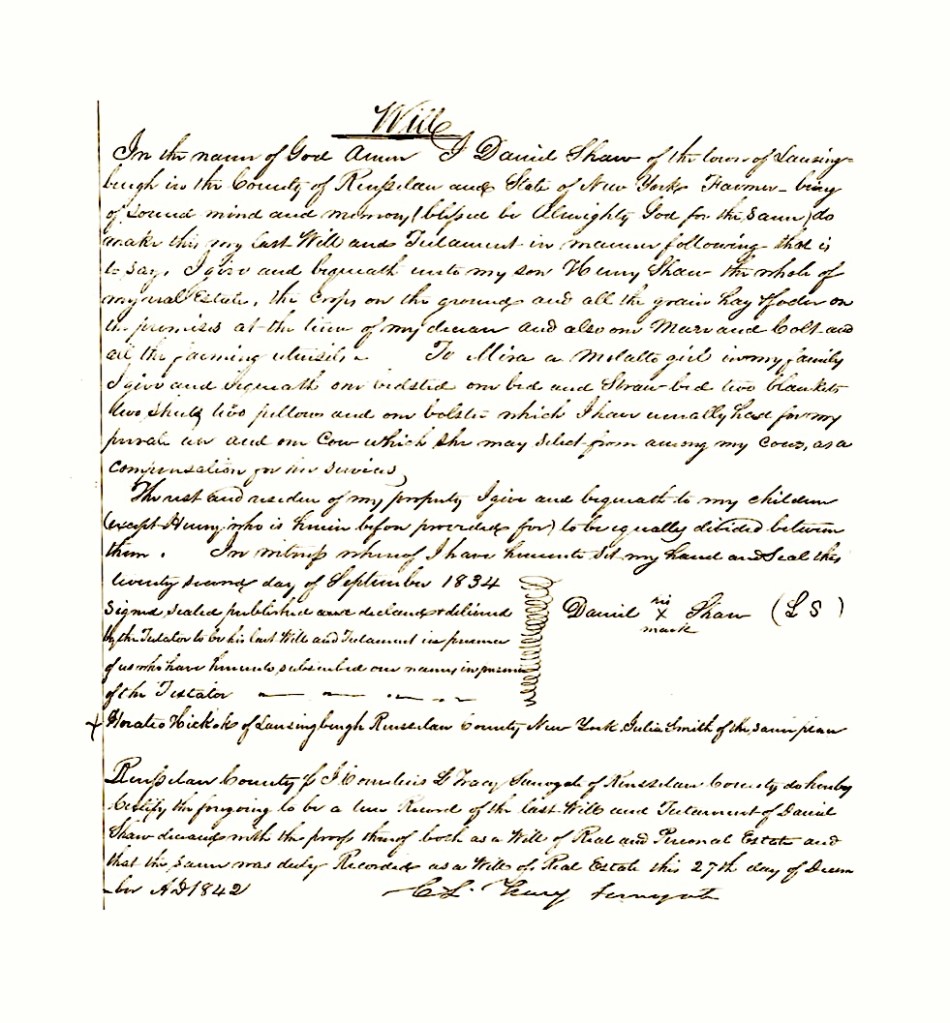

Lydia Doty died in November 1830, and consequently her husband Daniel was maybe feeling a little bit blue in the years afterward— or maybe not. Perhaps he was just prudent? We observed that he executed his Will on September 22, 1834, but continued to live on for almost eight more years, dying on August 13, 1842.

When we looked at the Will contents, we read that he left his son Henry “the whole of my real estate, the crops on the ground and all the grain, hay fodder on the premises at the time of my death and also one mare and one colt and all the farming utensils”. (It seems Henry never married, so perhaps he was living with his father in his older age?) For his other children (excepting for Henry who was provided for), he asked that his estate “be equally divided among them”.

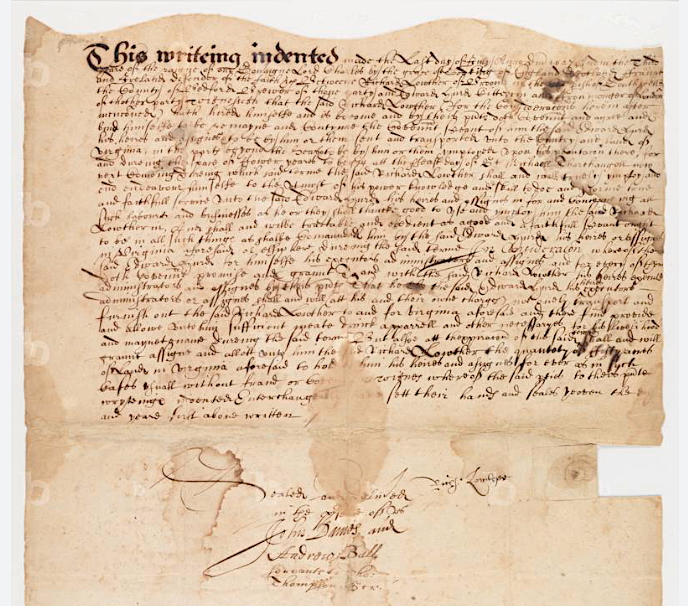

One of the most intriguing aspects of the Will is that after he indicated what he was providing to his son Henry, and before he mentions his other children, he specifically requests provision for a servant girl (we added commas to make the text understandable) —

To Misa, a Mulatto girl in my family, I give and bequeath one bedstead, one bed and straw-bed, two blankets, two sheets, two pillows, and one bolster, which I have usually had for my personal use, and one cow, which she may select from my cows, as a compensation for her services…

We checked the 1840 census to see if Daniel owned any slaves.* He did not. However, that census did indicate that there were three “Free Colored Persons” residing in the home, as follows:

- Two males, one under 10, and one between 10-24 years old

- One female, between 24-36 years old

*Slavery was fully abolished in New York following a gradual emancipation act passed in 1799 that freed children born after that date. An act on March 31, 1817, set the timeline for final emancipation, and the last enslaved people in the state gained freedom on July 4, 1827. (See footnotes).

We speculate that the Free Colored Person on the census (female) was Misa, and we wonder if the two males could have been her sons? By 1840, Daniel Shaw had been living in his Lansingburgh home for many years. When we looked at the ages for the other residents in the home, none of them aligned perfectly with the very scant knowledge we have about his children… Conceivably, he could have had a family boarding there. It makes sense that in his older age, and being a widower, he needed people around him. (6)

Crossing The Bridge

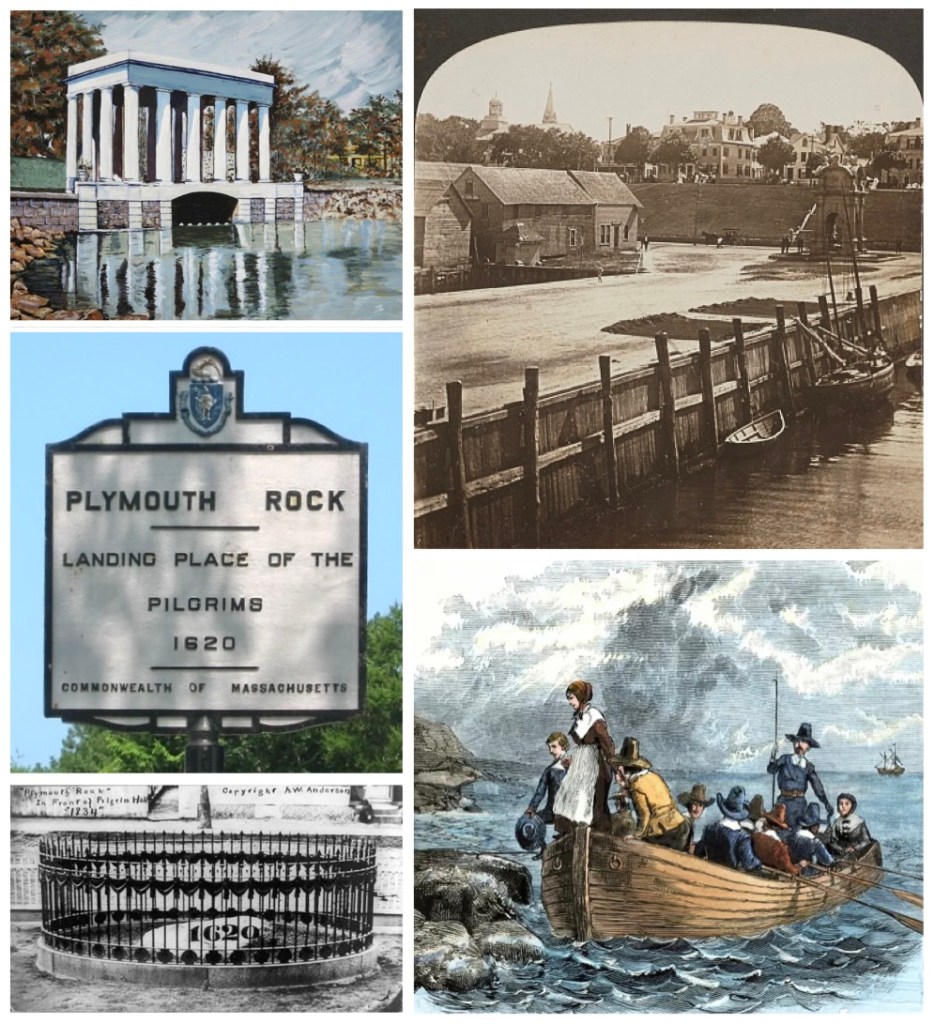

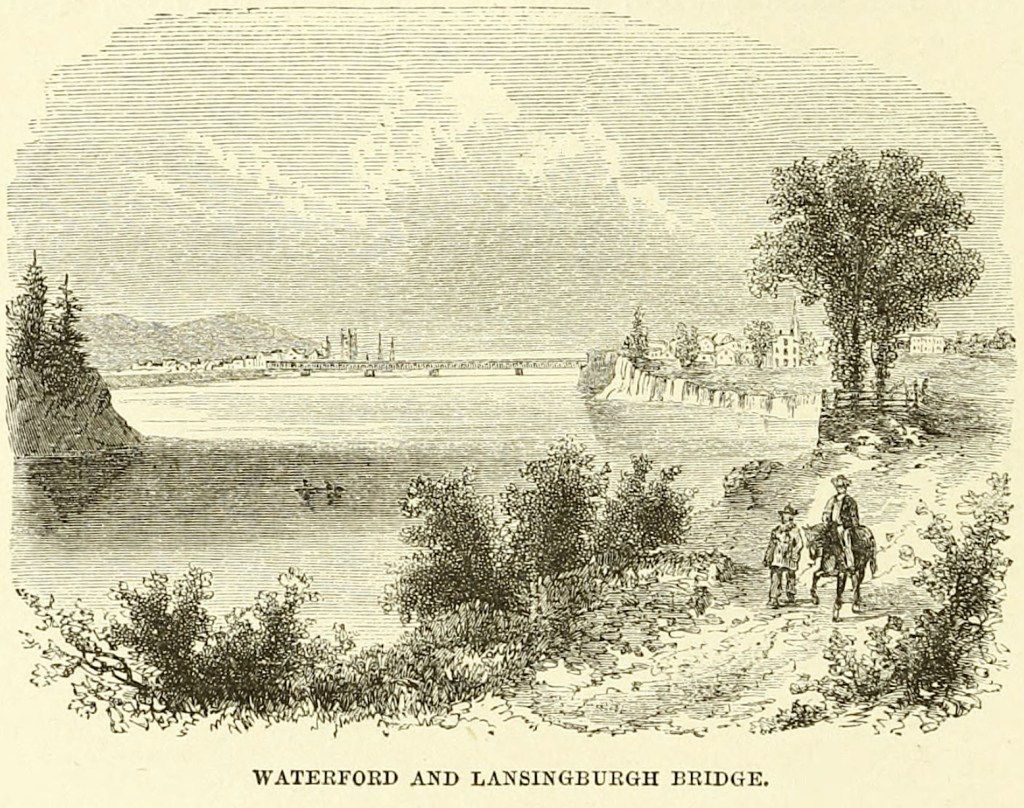

In the era we live in today, with the general ease of transportation, getting around is something we don’t pay much heed to. (Unless of course, we get stuck driving in traffic, or worse, we get a bit anxious because our luggage is taking much too long to show up at the carousel at the airport!) For our ancestors, getting around town took some real effort. Just imagine what it was like to cross the Hudson or Mohawk Rivers back then? It’s no wonder people got excited when a new bridge was built!

The Union Bridge was built between 1800-1810.

From a Wikipedia article on the History of Lansingburgh, “The structure which spans the Hudson River between Lansingburgh and Waterford, Saratoga county, known as the Union Bridge, is distinguished as being the oldest wooden bridge in the United States. It stands intact today as strong apparently as in the early days of the century. When the bridge was constructed it was deemed a marvel of engineering skill. How the public looked upon the structure at that time is manifested by the elaborate character of the exercises which attended its opening.

The day was a holiday in Lansingburgh. A ‘very numerous procession’ was formed at noon at Johnson & Judson’s hotel and marched to the bridge, and thence across to Waterford, ‘under the discharge of seventeen cannon’, where a dinner had been provided at Van Schoonhoven’s hotel at the expense of the stockholders of the bridge. Among the prominent persons in attendance were the governor, the secretary of state, the comptroller, ‘and a large number of respectable gentlemen from Albany and the adjacent villages’, who ‘partook in much harmony and conviviality’. The structure is 800 feet (240 m) long and thirty feet wide…”

In the next chapter, we will literally cross over this Union Bridge with our 4x Great Grandfather Orman Shaw, and learn about a union of another kind — that with his future wife Elizabeth. They will come to reside in the community of Halfmoon, Saratoga County. (7)

Following are the footnotes for the Primary Source Materials,

Notes, and Observations

Setting The Stage

(1) — four records

Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center at the Boston Public Library

A Map of the State of New York

by Simeon De Witt, circa 1804

https://collections.leventhalmap.org/search/commonwealth:p8418t73n

Note: For the map image.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Troy from Mount Ida

(No. 11 of The Hudson River Portfolio)

Various artists/makers, 1821–22

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/418421

Note: For the river and town image.

Wade & Croome’s Panorama of the Hudson River from New York to Waterford

[electronic resource]

by William Wade, John Disturnell, and William Croome, circa 1847

https://archive.org/details/ldpd_11290386_000/page/n1/mode/2up

Note: For the cover image, and the panoramic Point-of-Interest view #153 of Lansingburgh, New York

Troy, New York

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Troy%2C_New_York

Note: For the text.

A Tree of Welfare

(2) — two records

50 Objects — New York’s Capital Region in 50 Objects

Witenagemot Oak Peace Tree

https://www.albanyinstitute.org/online-exhibition/50-objects/section/witenagemot-oak-peace-tree

Note: For the tree photograph.

Schaghticoke, New York

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schaghticoke,_New_York

Note: For information about the Tree of Welfare and Albany land ownership.

Getting To Know Daniel Shaw

(3) — four records

(DDFA)

Doty-Doten Family in America

Descendants of Edward Doty, an Emigrant by the Mayflower, 1620

by Ethan Allan Doty, 1897

https://archive.org/details/dotydotenfamilyi00doty/page/512/mode/2up

Book pages: 513, Digital pages: 512 /1048

Note: For the text.

History of the Seventeen Towns of Rensselaer County, From the Colonization of the Manor of Rensselaerwyck to the Present Time

by Arthur James Weise, circa 1880

https://archive.org/details/cu31924064123015/page/n5/mode/2up?view=theater

Book page: 34, Digital page: 40/168, Left and right columns at bottom.

Note: For the names Daniel Shaw and Joseph “Dody” as observed within the text.

Empire State Society of the Sons of the American Revolution

New York Revolutionary War Tax Lists

https://www.ess-sar.org/pages/nys_taxlists.html

Note: For the text.

Empire State Society of the Sons of the American Revolution

New York Revolutionary War Tax Lists by County — Albany

October 1779 Land and Property Tax Lists — Schachtakoke

https://www.ess-sar.org/pages/nystax_counties/nys_taxlists_county_albany_schachtakoke_october-1779.html

Document page: 4, Digital page: 5

Note 1: Entry 16 lists Danl Shaw of Cohoes.

Note 2: Three siblings of Lydia Doty are listed: Peter, Orman, and Jacob Doty.

The Colonial Militias of New York

(4) — seven records

U.S., Revolutionary War Rolls, 1775-1783 for Daniel Shaw

New York > Willett’s Regiment of Levies, 1781-1783 (Folder 173)

— Various Organizations (Folder 181)

Digital page: 226/644

https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/4282/records/1725089

Note 1: “An account of certificates” with Daniel Shaw being listed 25th from the bottom. Indications read “Investigation shows that a large number of the names on this records as of Col. Peter Yates’ Reg’t. NY”

Note 2: Further notations on digital page 228/644 indicate that payments were paid on 3 March 1789 in Lansingburgh by John VanRensselaer.

JAR: Journal of the American Revolution

How Was The Revolutionary War Paid For?

https://allthingsliberty.com/2015/02/how-was-the-revolutionary-war-paid-for/

Note: For reference.

Albany County Militia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albany_County_militia

Note: For the text.

American Wars

Albany County Militia – 14th Regiment

https://www.americanwars.org/ny-american-revolution/albany-county-militia-fourteenth-regiment.htm

Note: For the listings of the Shaws and the Dotys.

Fandom

American Revolutionary War Wiki

14th Albany County Regiment of Militia

https://arw.fandom.com/wiki/14th_Albany_County_Regiment_of_Militia#cite_note-1

Note: For the text.

2nd New York Regiment

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2nd_New_York_Regiment

Note: For the data.

Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York

by Various Authors, circa 1853

(is enclosed within)

New York In The Revolution, Volume One

by The Board of Regents and Berthold Fernow, circa 1887

https://archive.org/details/documentsrelativ15alba/page/n9/mode/2up

Note 1: On book page 469 —Daniel Shaw, private, and Peter Doty, private, are listed on the Roster of the State Troops as being members of Yate’s Regiment.

Note 2: On book page 361 —Jacob Doty, private, and Orman Doty, private, are listed on the Roster of the State Troops as being members of Van Rensselaer’s Regiment.

The Doty Surname Gives Way to Shaw

(5) — eleven records

The Hammond-Harwood House Museum

18th Century Marriage

https://hammondharwoodhouse.org/18th-century-marriage/

Note: For the colonial wedding image.

Schaghticoke, New York

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schaghticoke,_New_York

Note: For information about Rensselaer County in 1791.

(DDFA)

Doty-Doten Family in America

Descendants of Edward Doty, an Emigrant by the Mayflower, 1620

by Ethan Allan Doty, 1897

https://archive.org/details/dotydotenfamilyi00doty/page/512/mode/2up

Book pages: 513, Digital pages: 512 /1048

Note: For the text.

Lydia Shaw

in the U.S., Find a Grave Index, 1600s-Current

https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/60525/records/81992848?tid=&pid=&queryId=7c715aee-d3b7-4366-ba38-8699a4dee0c0&_phsrc=RPj2&_phstart=successSource

and

Lydia Shaw

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/121224259/lydia-shaw

Note: For the data.

Daniel Shaw

in the 1790 United States Federal Census

https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/5058/records/235427?tid=&pid=&queryId=1604fcd7-4f55-449e-8ae3-7d9d14acac82&_phsrc=UbN8&_phstart=successSource

Book page: 355, Digital page: 324/647, Left column, entry #20 from the bottom.

Note: For the data. This indicates that the family was living Pittstown.

1790 Census Records

https://www.archives.gov/research/census/1790

Note: For the data.

Daniel Shaw

in the 1800 United States Federal Census

New York > Rensselaer > Scaghticoke

https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/7590/records/270758

Book page: 782 (handwritten), Digital page: 9/9

Note: For the text.

1800 Census Records

https://www.archives.gov/research/census/1800

Note: For the data.

William Shaw

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/106338154/william-shaw

Note: For the obituary profile from an uncredited Kingston, New York newspaper. There are errors in the profile, such as his birthplace. He was not born in Dutchess County.

Hiram Shaw

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/142742279/hiram-shaw

Note: We speculate that he may have committed suicide.

Perhaps He Was A Prudent Man?

(6) — four records

[Record of the Will of Daniel Shaw]

New York, Probate Records, 1629-1971 > Rensselaer > Wills 1842-1843 vol 33

https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GY4J-6ST?lang=en&i=167

Book pages: 279-285, Digital pages (images): 168-171/277

Note: The first six pages are notices to all the siblings of the probate. The actual Will begins on book page 285, or image 171.

The Historical Society of the New York Courts

When Did Slavery End in New York?

https://history.nycourts.gov/when-did-slavery-end-in-new-york/

Note: Our text was derived from this article.

Daniel Shaw

in the 1840 United States Federal Census

https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/8057/records/3781404?tid=&pid=&queryId=a0d38961-eb39-4ef6-8a80-0f8cea30f959&_phsrc=Szr6&_phstart=successSource

Note: For the data.

1840 Census Records

https://www.archives.gov/research/census/1840

Note: For the data.

Crossing The Bridge

(7) — two records

The Hudson, From the Wilderness to the Sea

by Benson John Lossing, 1866

https://archive.org/details/hudsonfromwilder00lossi/page/108/mode/2up

Book page: 108, Digital page: 124/486

Note: For the bridge image.

History of Lansingburgh, New York

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Lansingburgh,_New_York

Note: For the text.