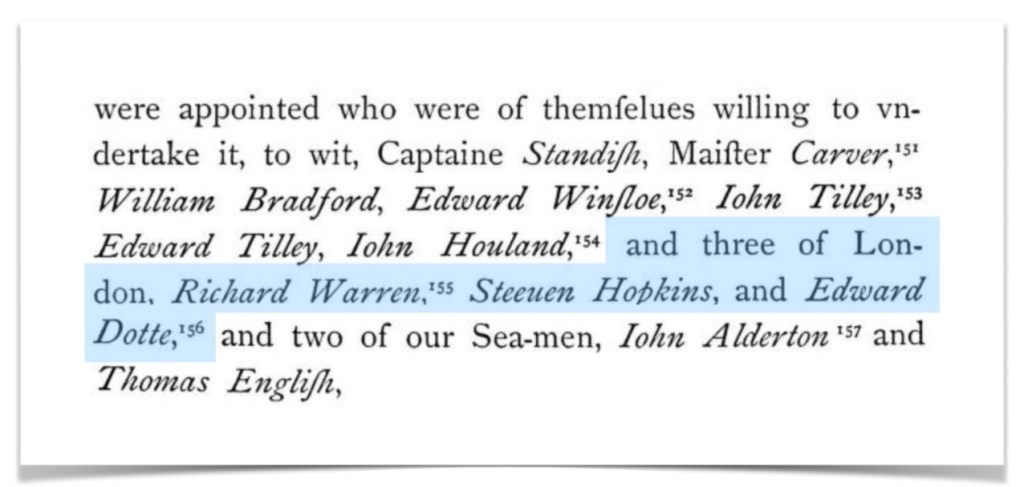

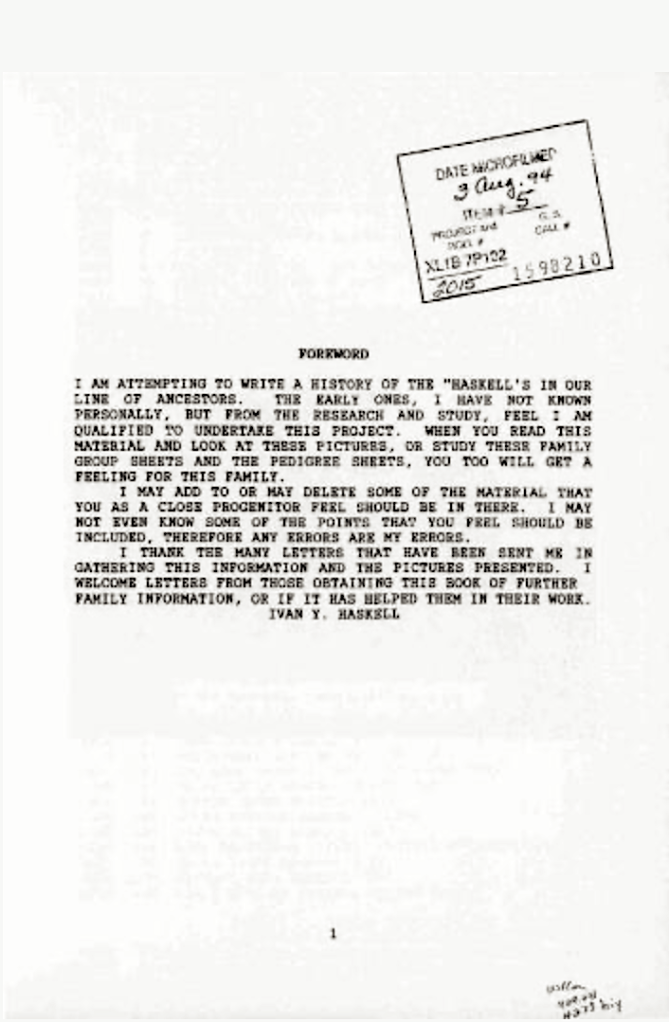

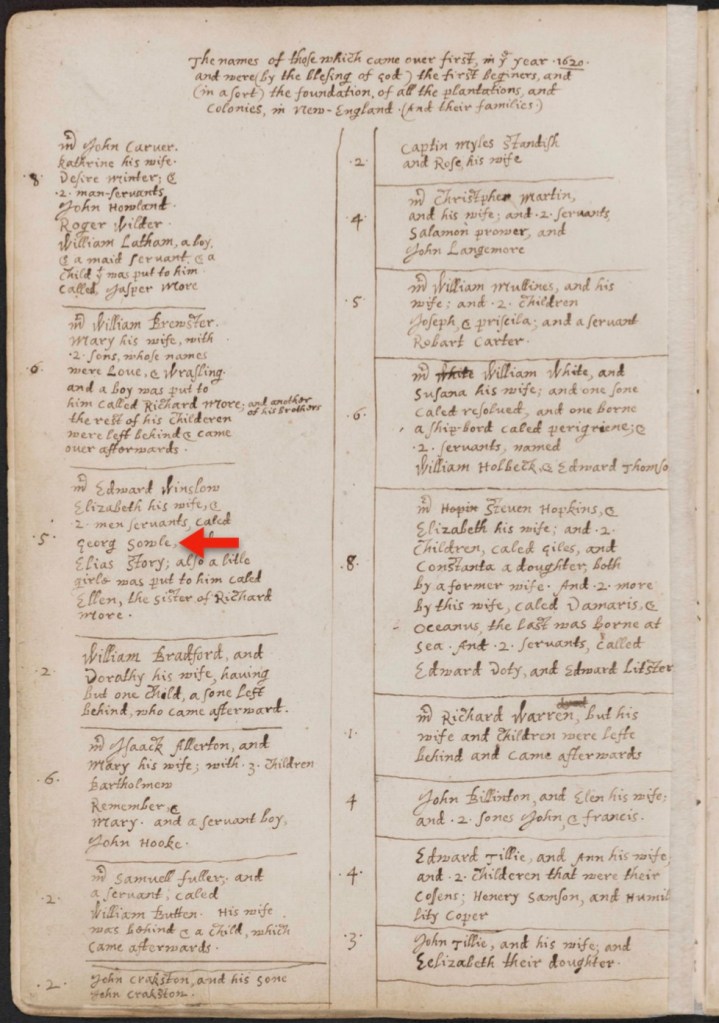

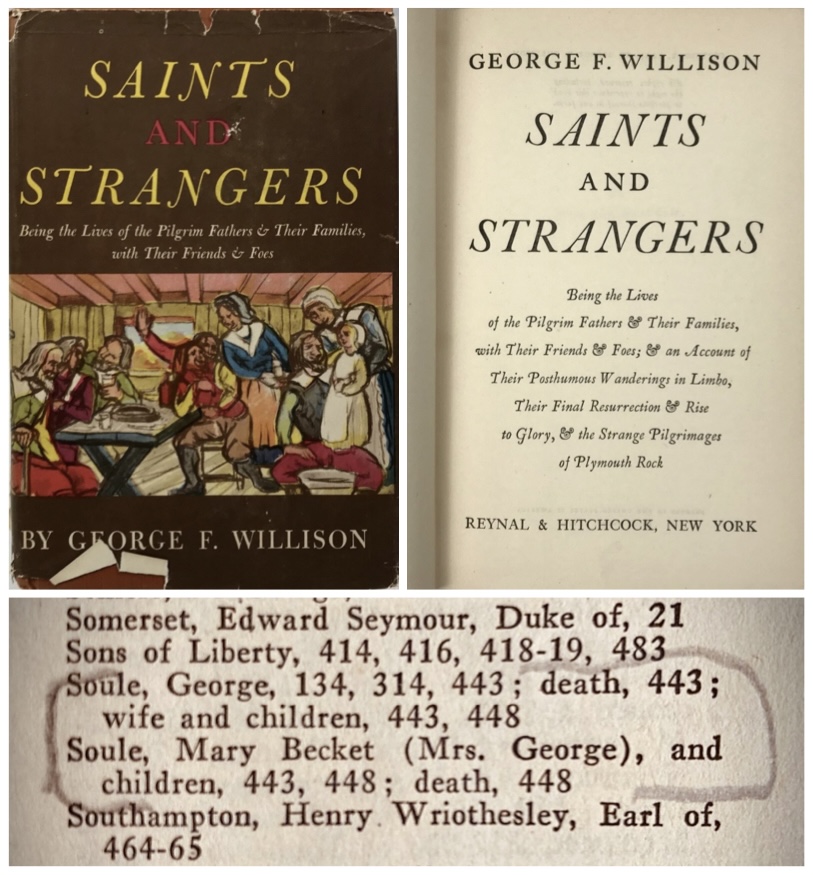

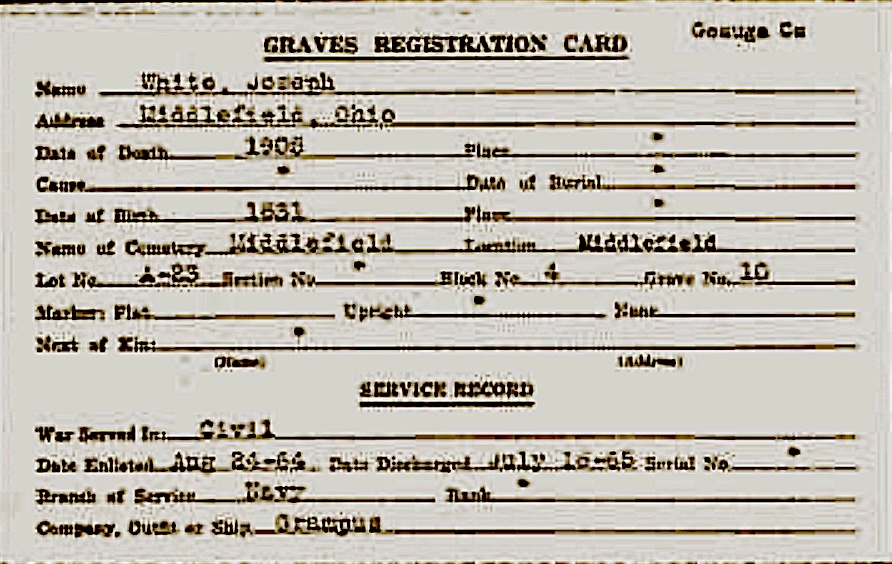

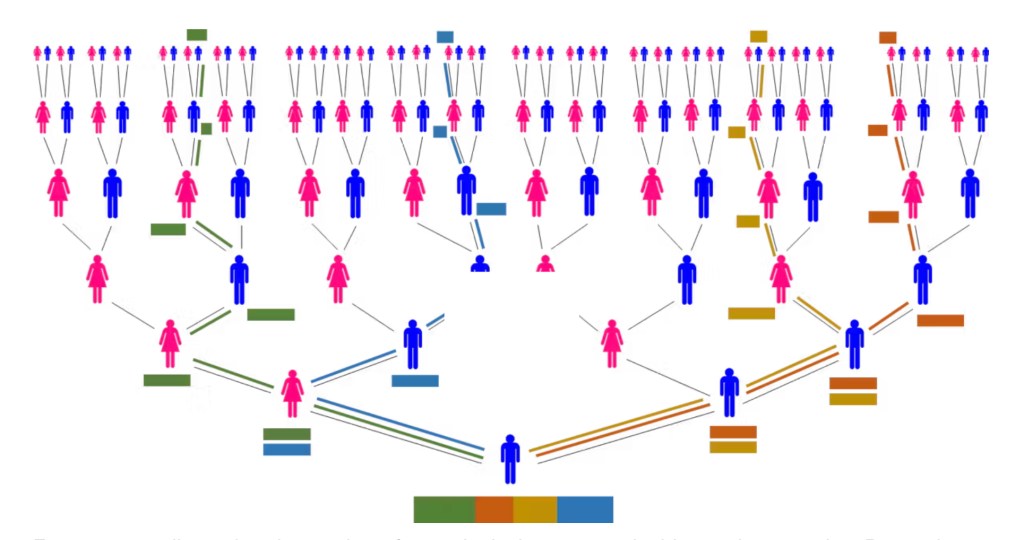

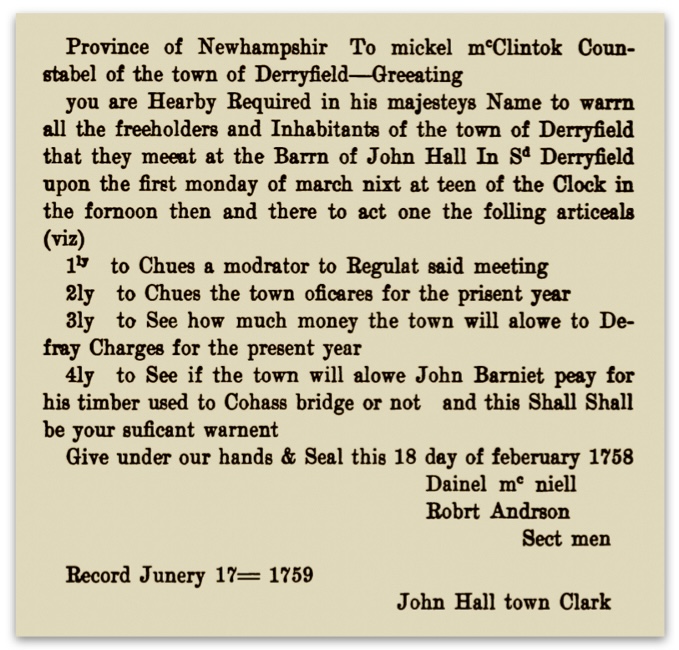

This is Chapter 3 of 3, being the last chapter that follows this family line. (Again, as a reminder), in total there are 6 chapters: the first set of 3 chapters is written in English; second set of 3 chapters is translated into Portuguese.

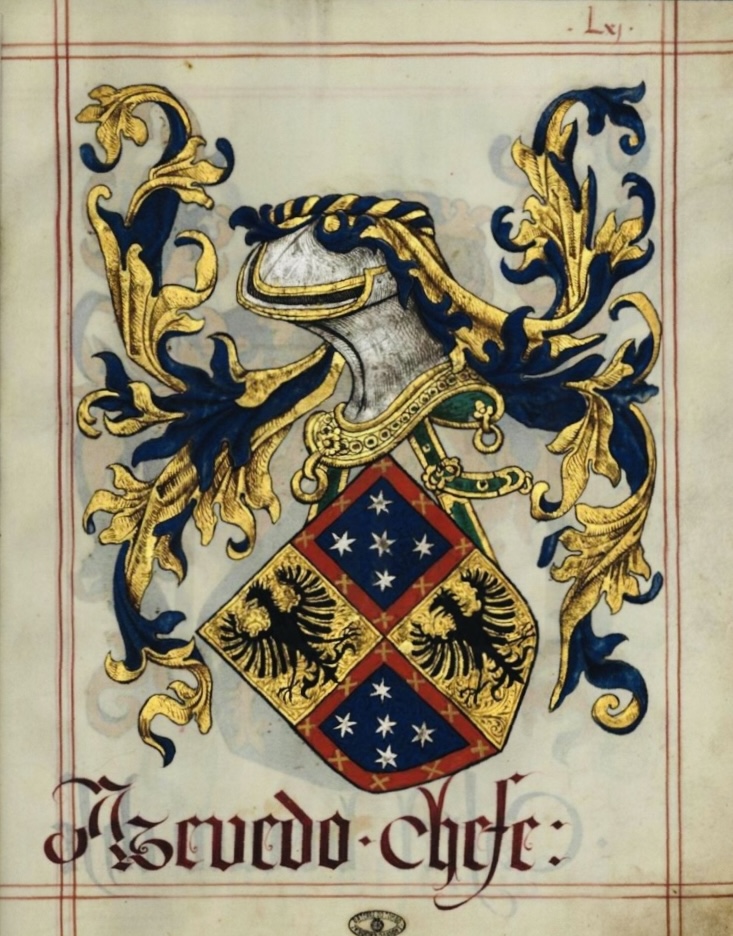

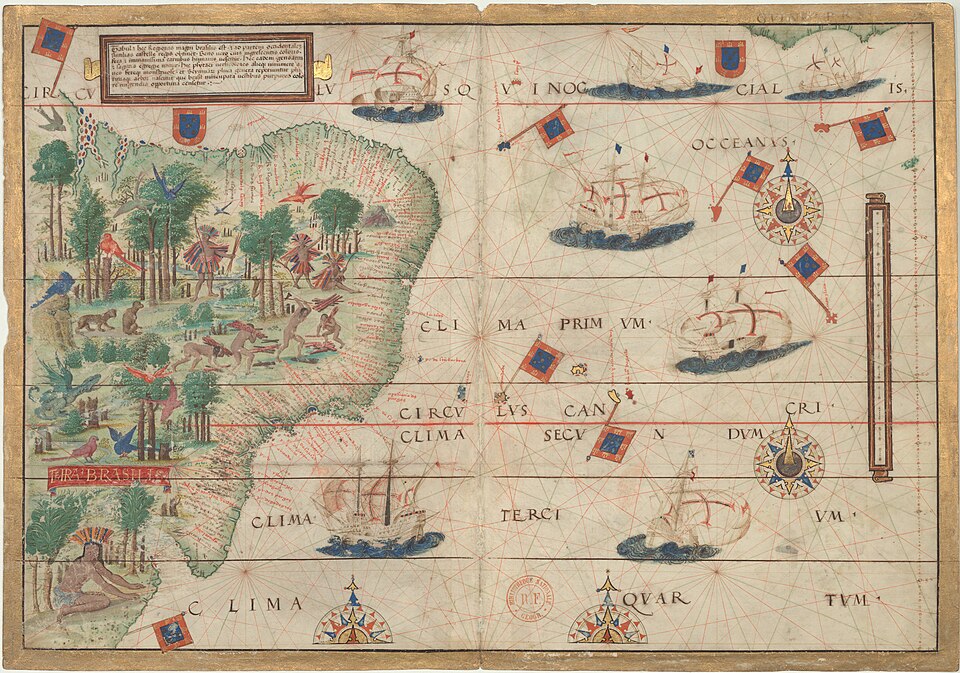

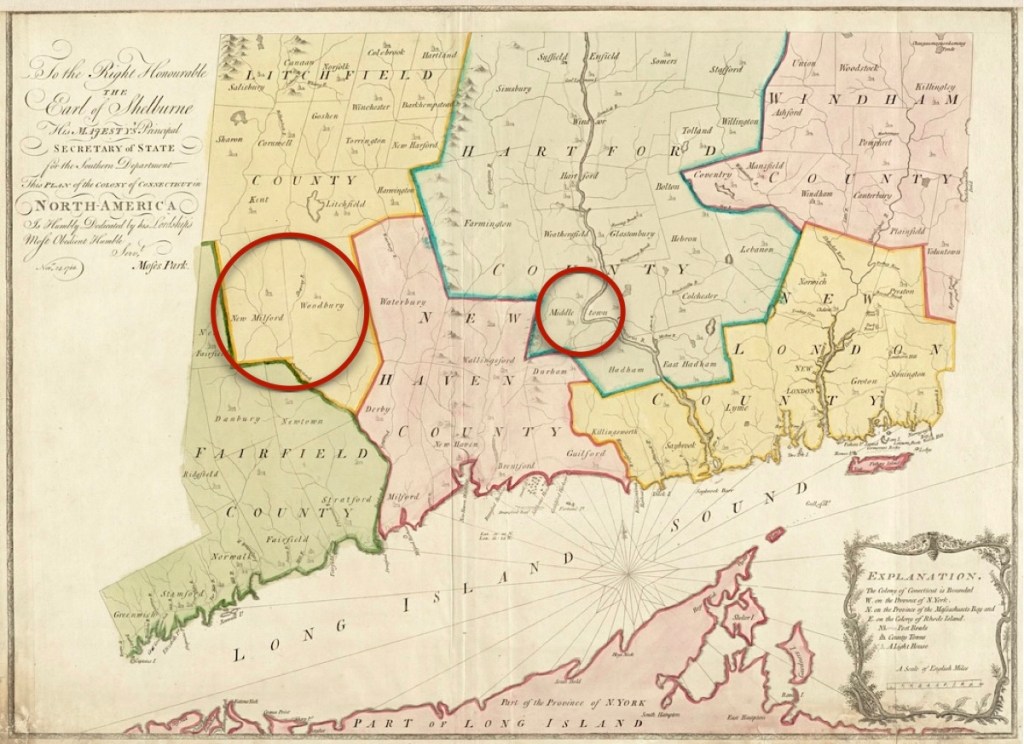

(Image courtesy of Librairie Elbé, Paris).

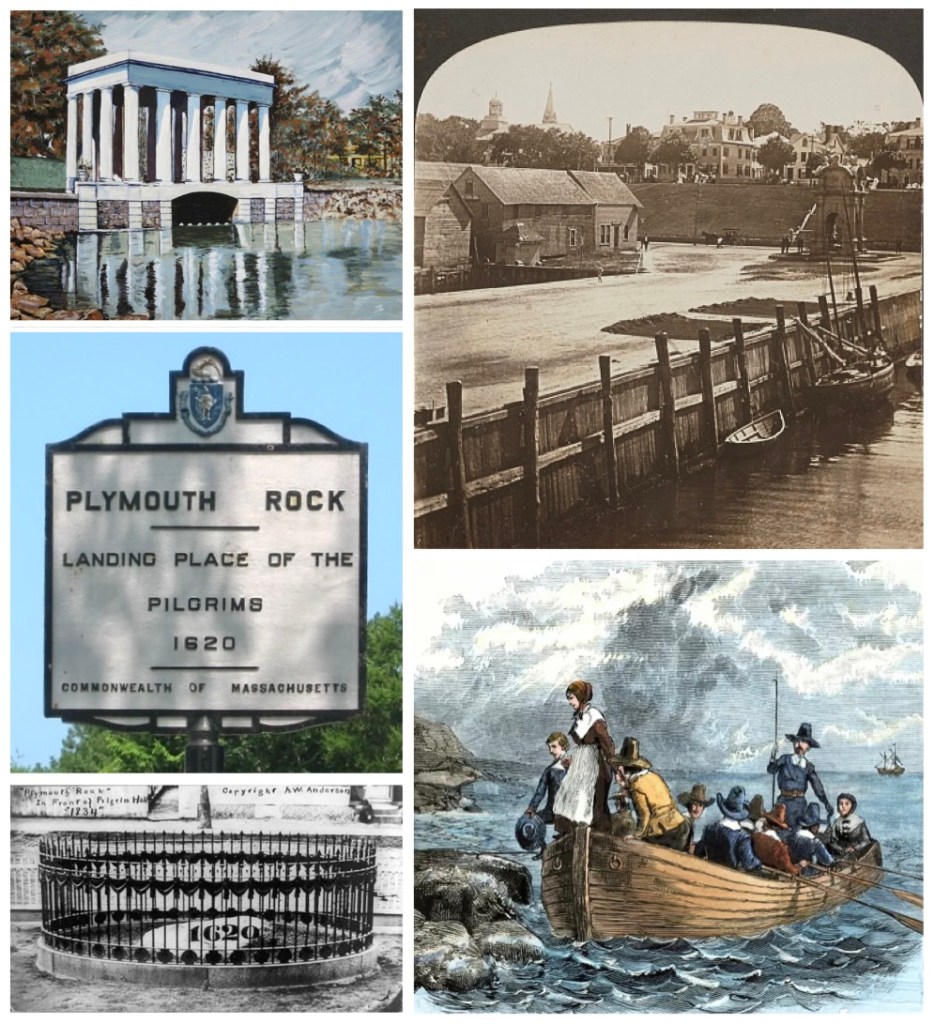

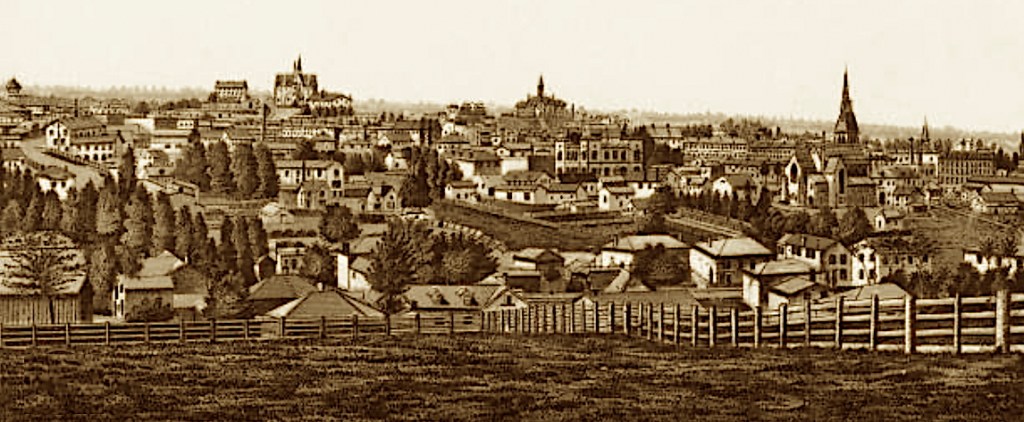

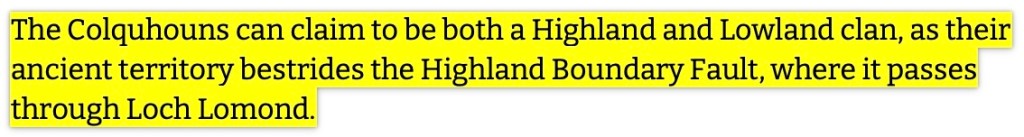

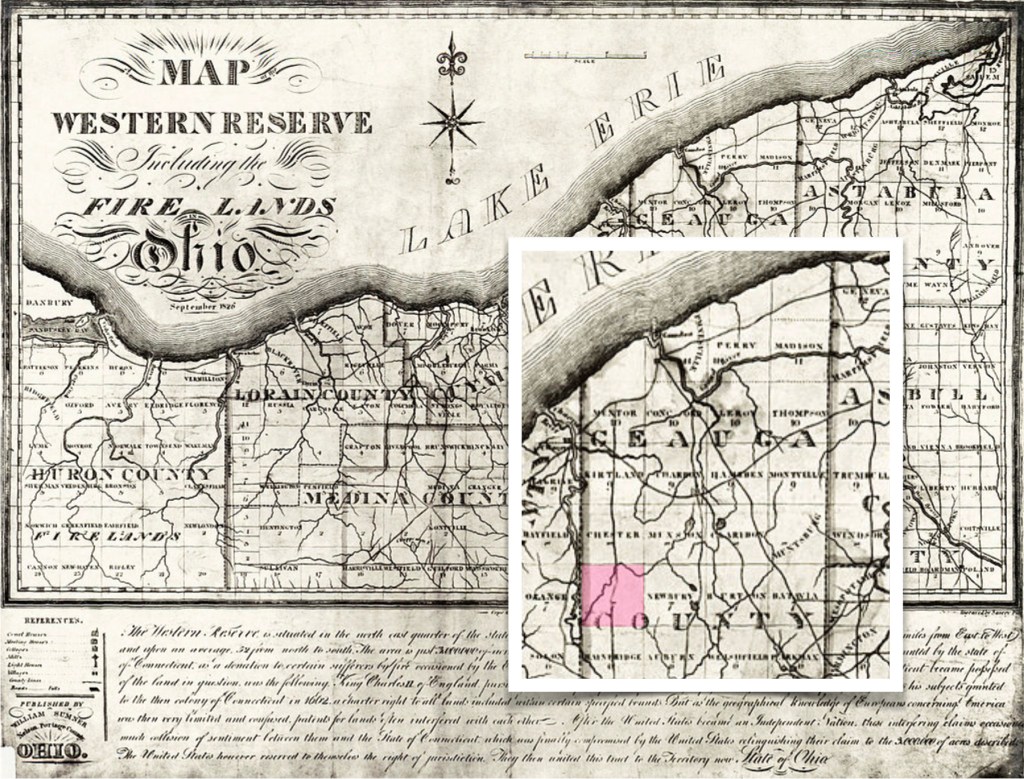

A Place Quite Apart

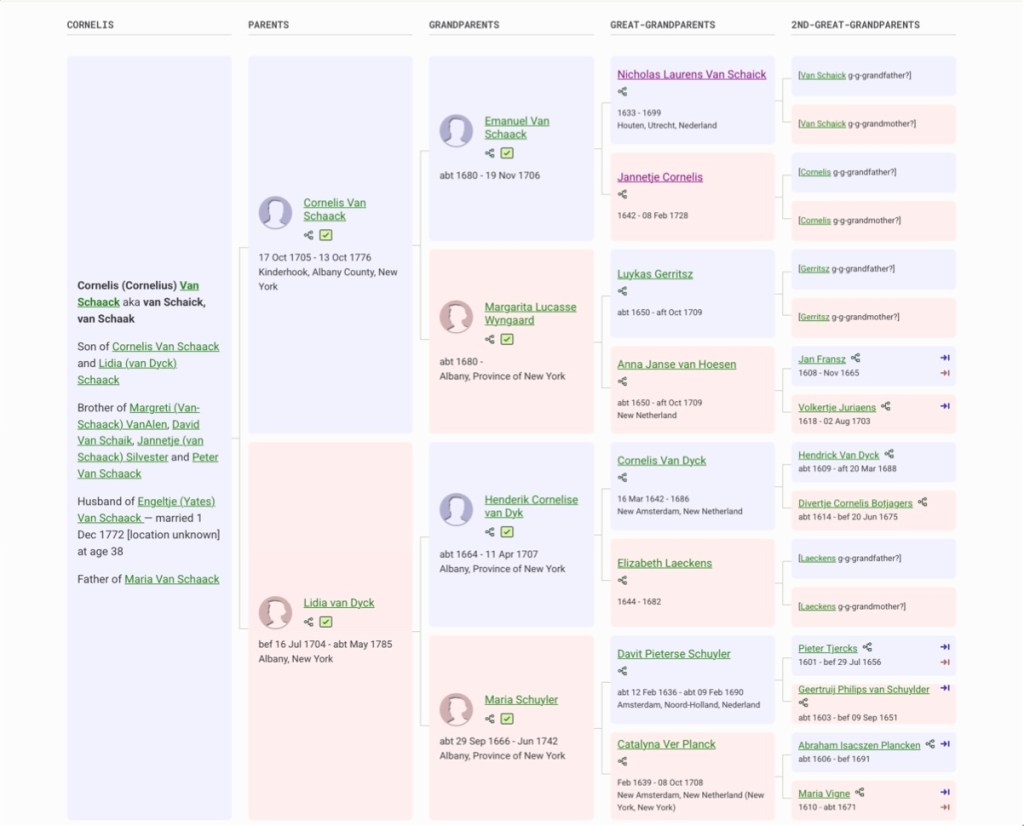

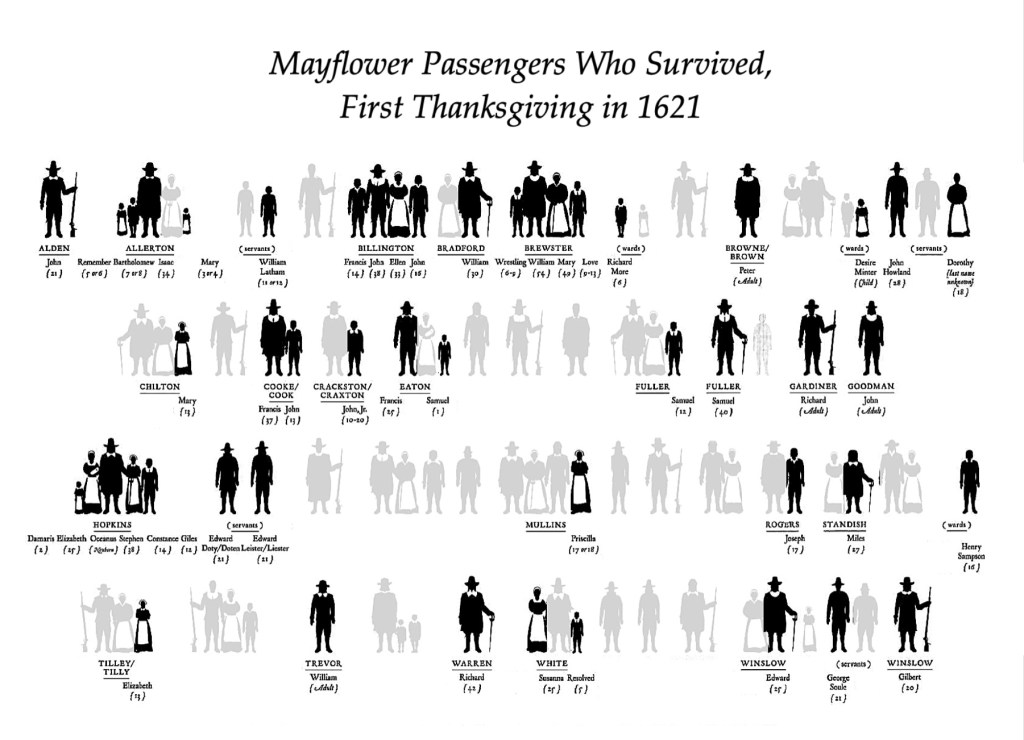

The Coutinho and Oliveira families are traditional Brazilian Roman Catholic families, descended from Portuguese immigrants. However, the northeastern state of Bahia, which they immigrated to, is a unique place quite apart from the rest of Brazil. There are historical reasons for this… (1)

Catholicism is the Foundational Religion of Brazil

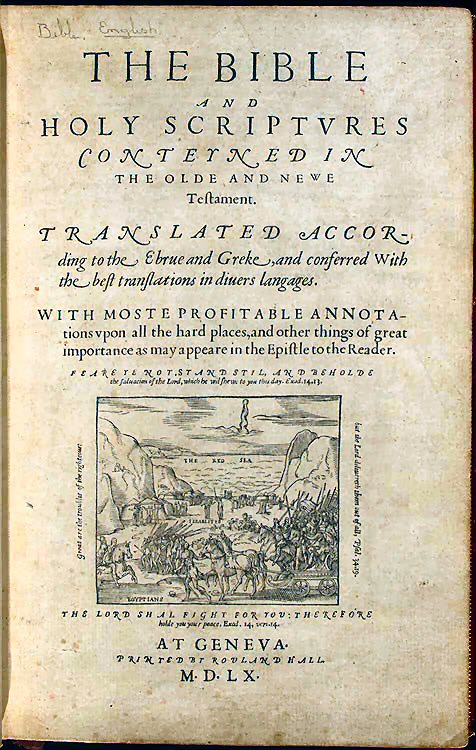

“According to the tradition, the first Catholic mass celebrated in Brazil took place on April 26, 1500. It was celebrated by a priest who arrived in the country along with the Portuguese pirates and explorers to claim possession of the newfound land. The first diocese in Brazil was erected more than 50 years later, in 1551.

Brazil’s strong Catholic heritage can be traced to the Iberian missionary zeal, with the 15th-century goal of spreading Christianity. The Church missions began to hamper the government policy of exploiting the natives. [Thus] in 1782 the Jesuits were suppressed, and the government tightened its control over the Church. [In the present day,] the Catholic Church is the largest denomination in the country, where 119 million people, or 56.75% of the Brazilian population, were self-declared Catholics in 2022. These figures make Brazil the single country with the largest Catholic community in the world.” There is a large pantheon of saints in the Catholic tradition. (Wikipedia and Google)

Comment: There are more Roman Catholics in Brazil than there are in Italy, simply because the population of Brazil is much greater than that of Italy. It would be very appropriate to say that Catholicism is an institutionalized religion in Bahia. Specifically, sources cite that there are more than 365 historic cathedrals and churches just in Salvador da Bahia alone. (One for each day of the year — So this makes us ponder, what about Leap Year Day? Instead of going to church, does everyone get a day off to go to the beach?) (2)

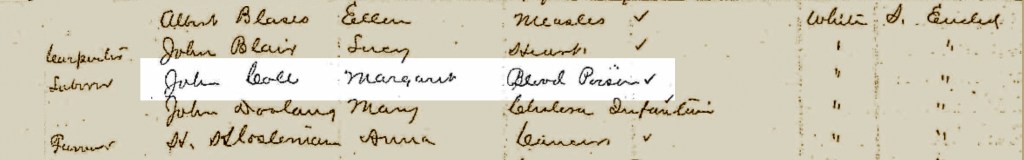

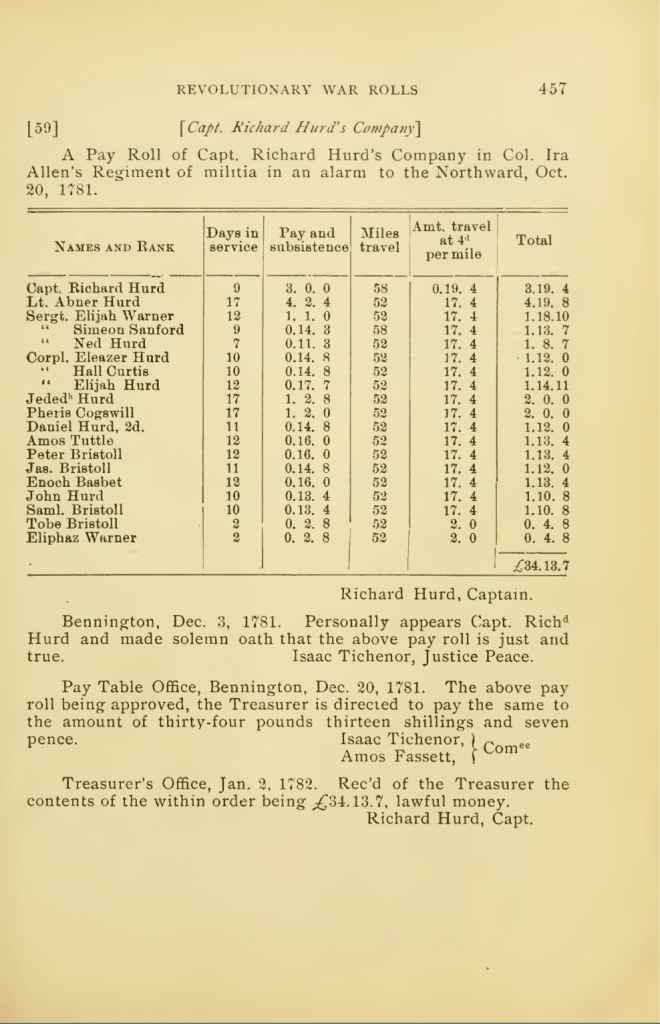

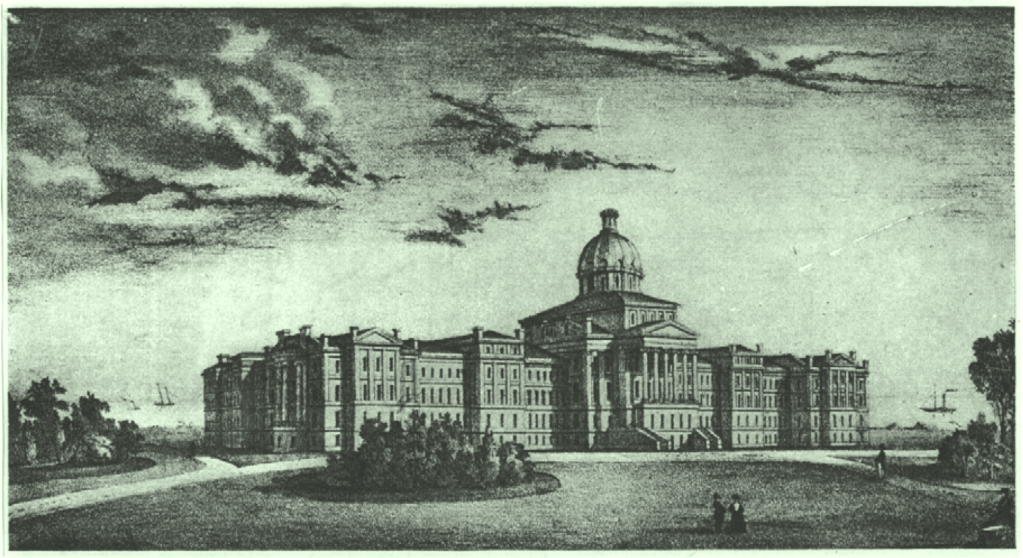

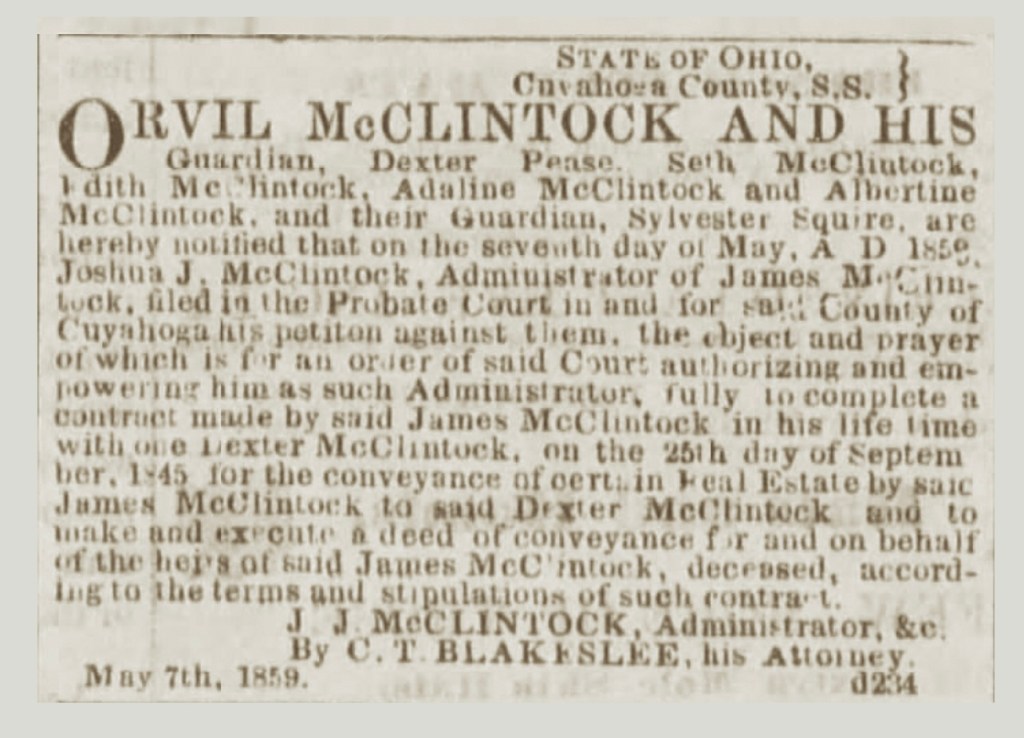

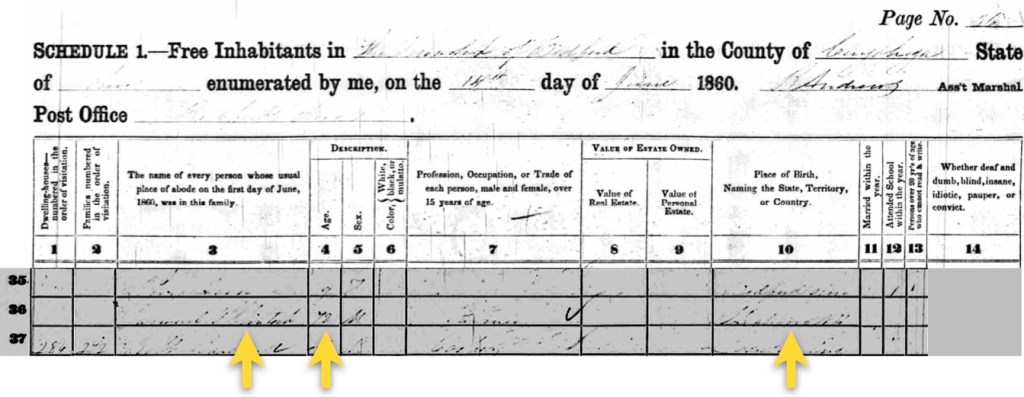

Slavery Did Not Officially End Until 1888

“During the Atlantic slave trade era, Brazil imported more enslaved Africans than any other country in the world. Out of the 12 million Africans who were forcibly brought to the New World, approximately 5.5 million were brought to Brazil between 1540 and the 1860s. The mass enslavement of Africans played a pivotal role in the country’s economy and was responsible for the production of vast amounts of wealth. In the first 250 years after the colonization of the land, roughly 70% of all immigrants to the colony were enslaved people.

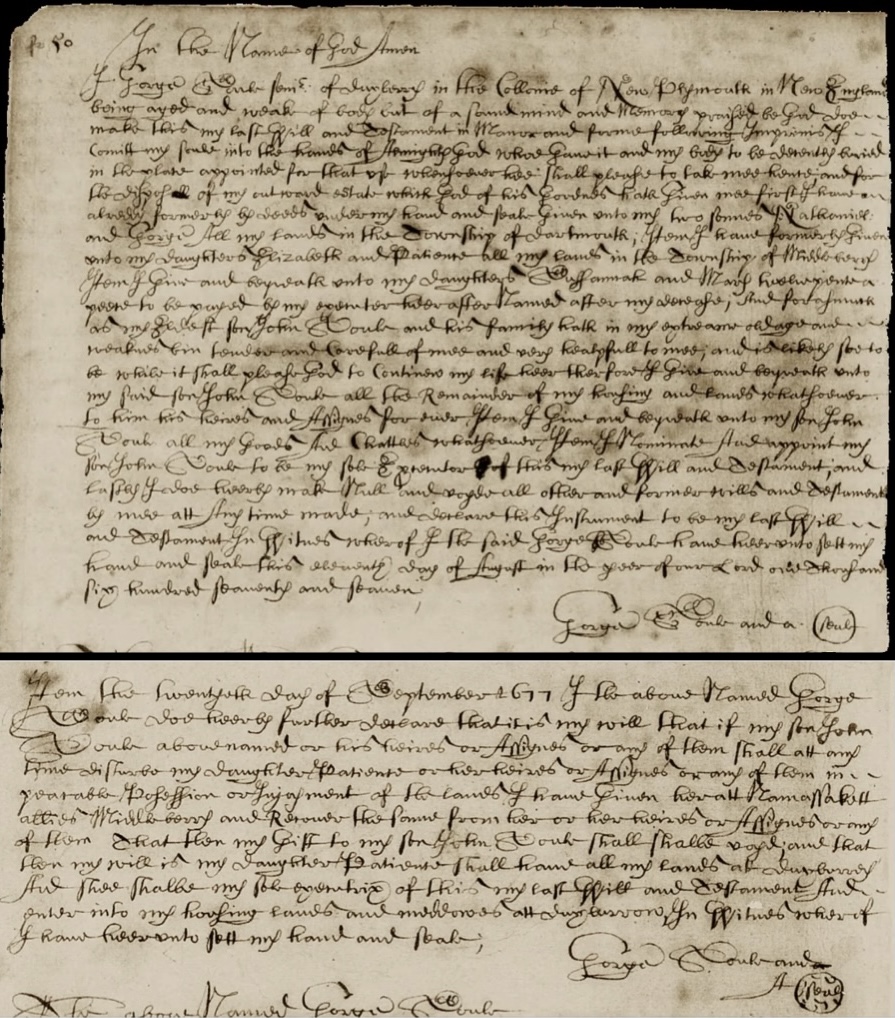

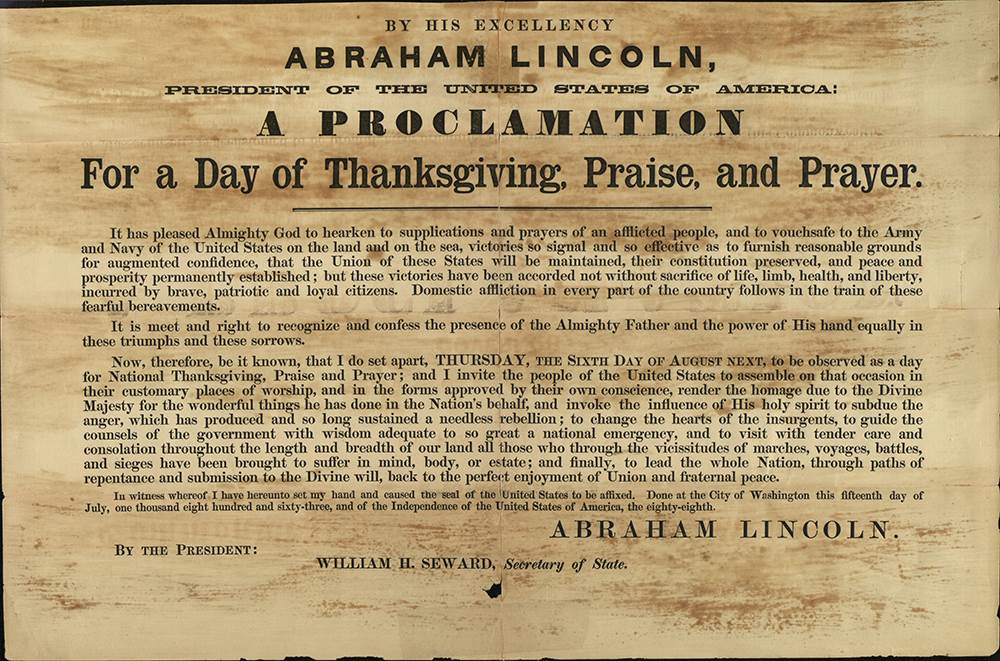

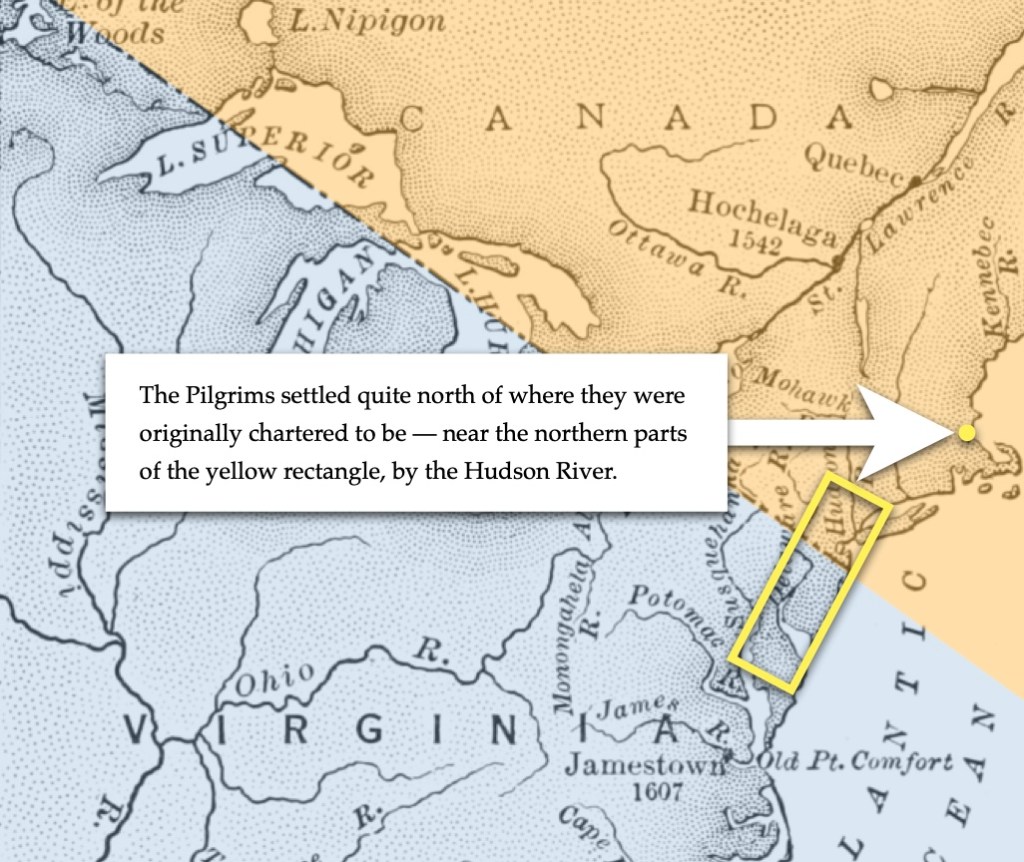

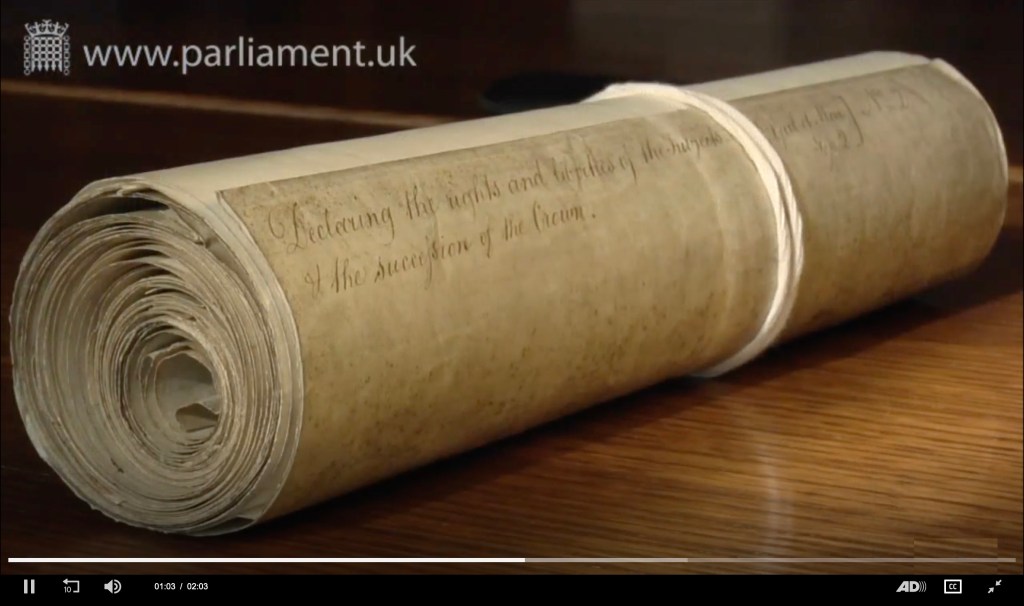

Slavery was not legally ended nationwide until 1888, when Isabel, Princess Imperial of Brazil, promulgated the Lei Áurea (Golden Act). The Lei Áurea was preceded by the Rio Branco Law of September 28, 1871 (the Law of Free Birth), which freed all children born to slave parents, and by the Saraiva-Cotegipe Law (the Law of Sexagenarians), of September 28, 1885, that freed slaves when they reached the age of 60. Brazil was the last country in the Western world to abolish slavery.” (Wikipedia, see footnotes). (3)

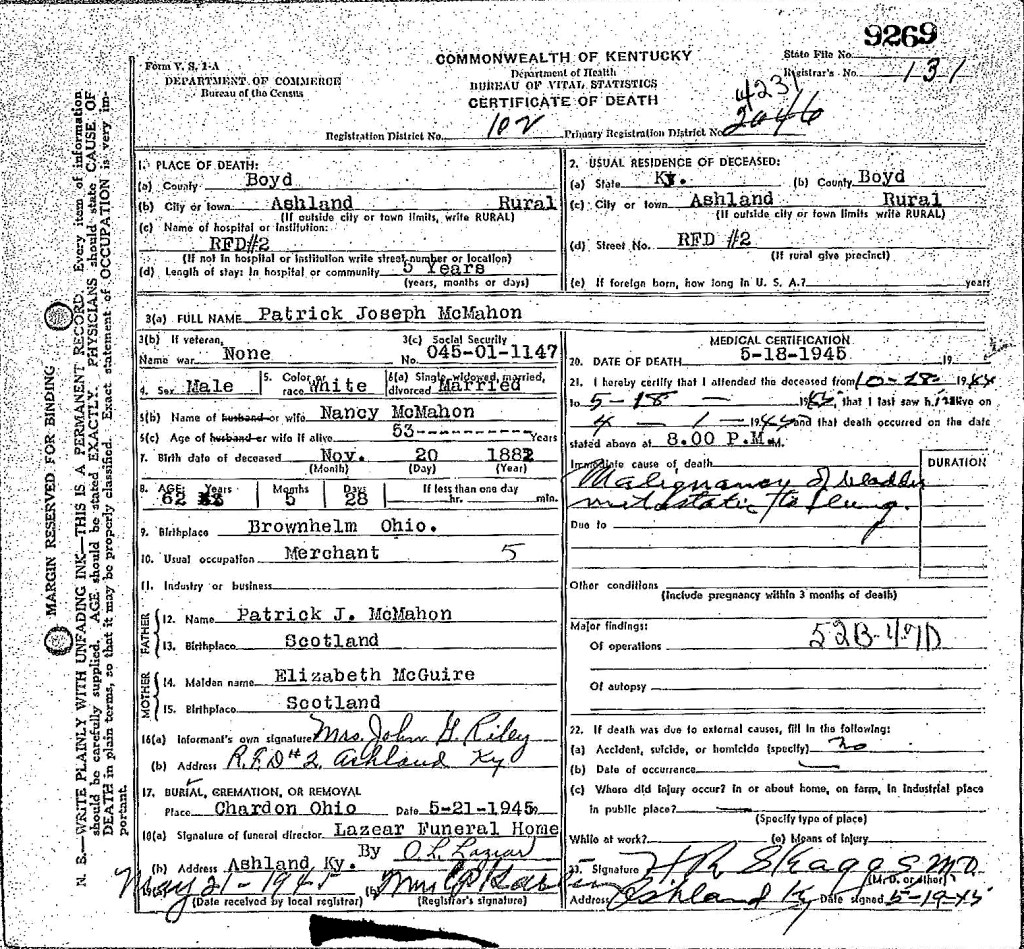

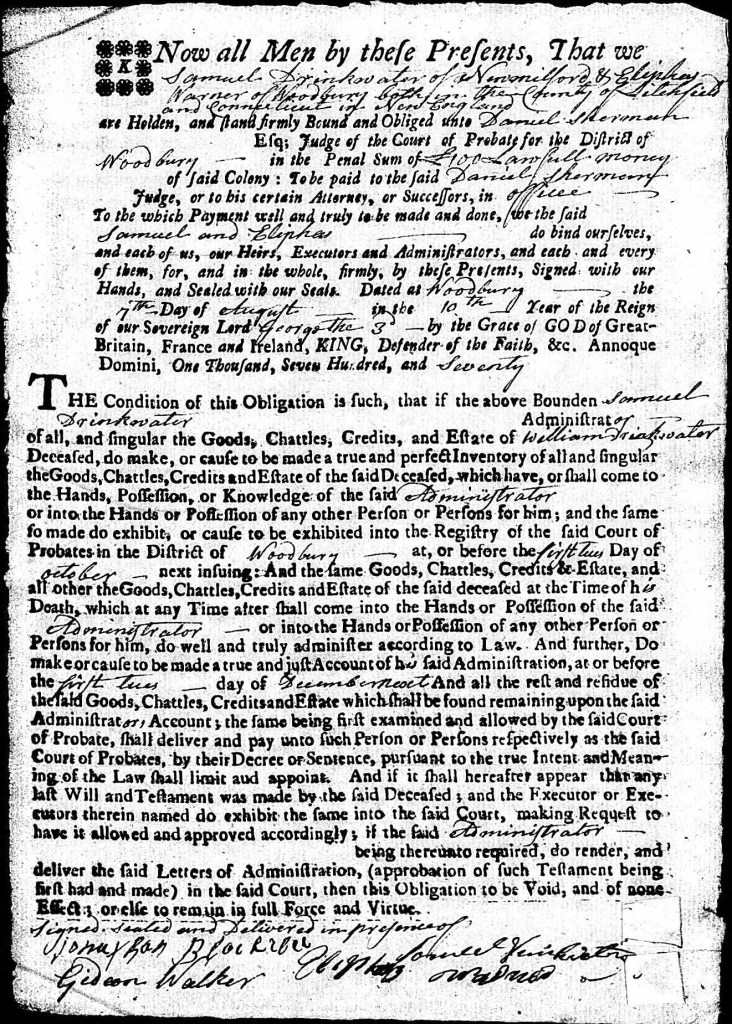

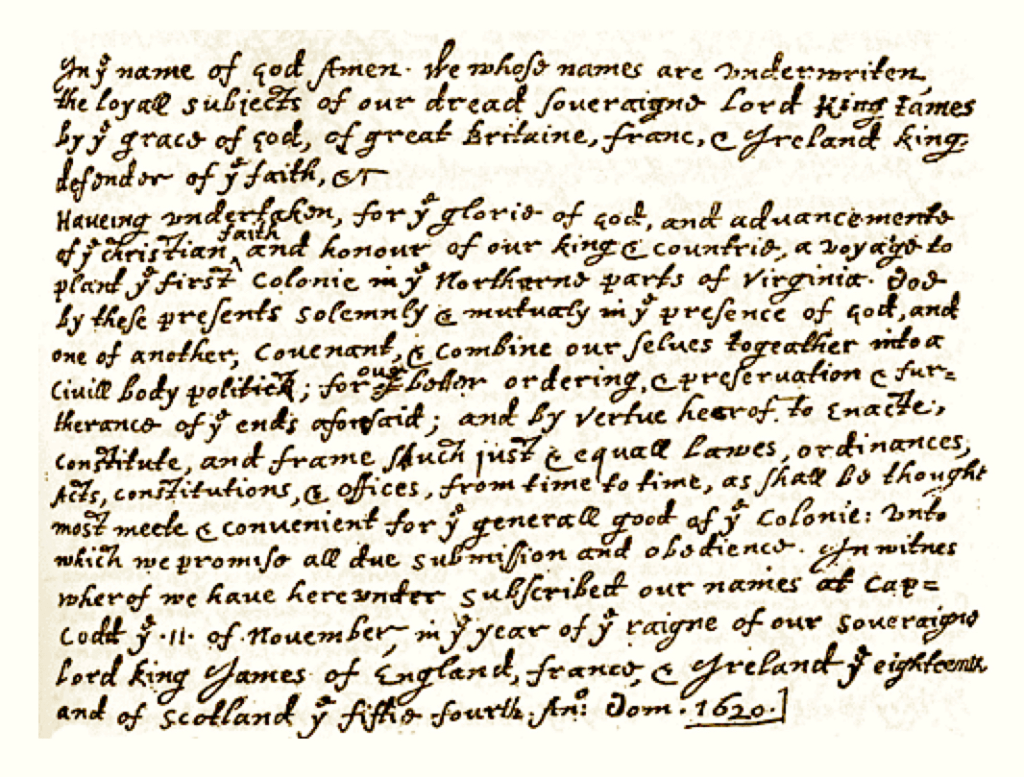

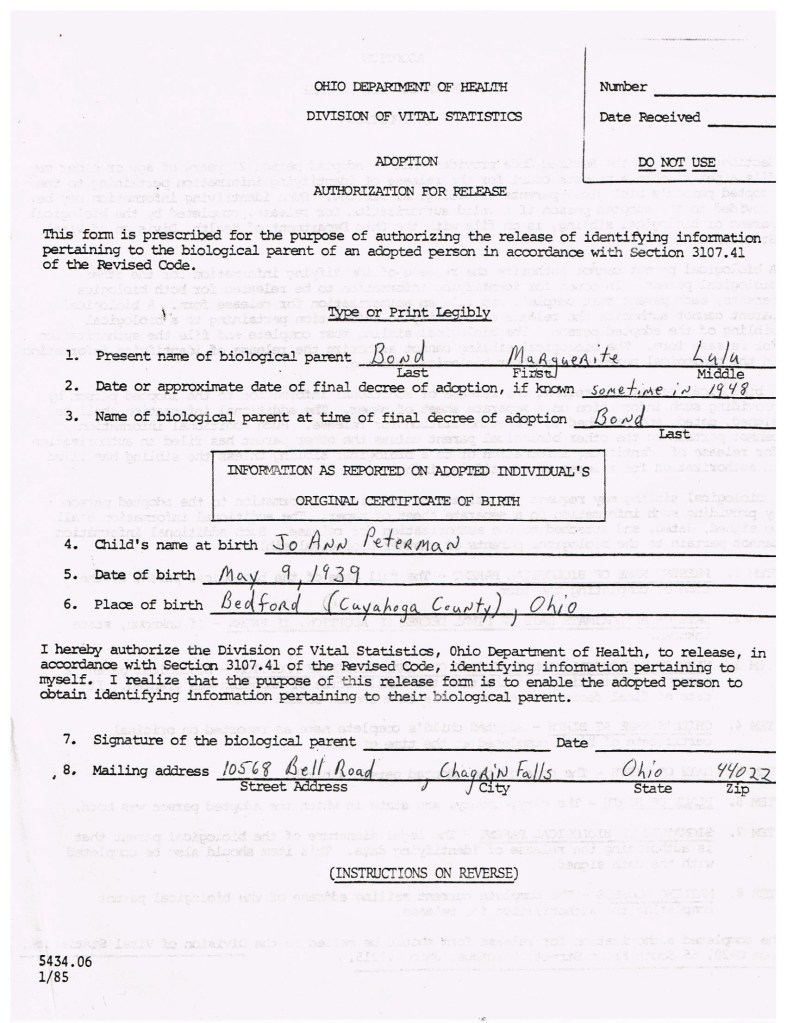

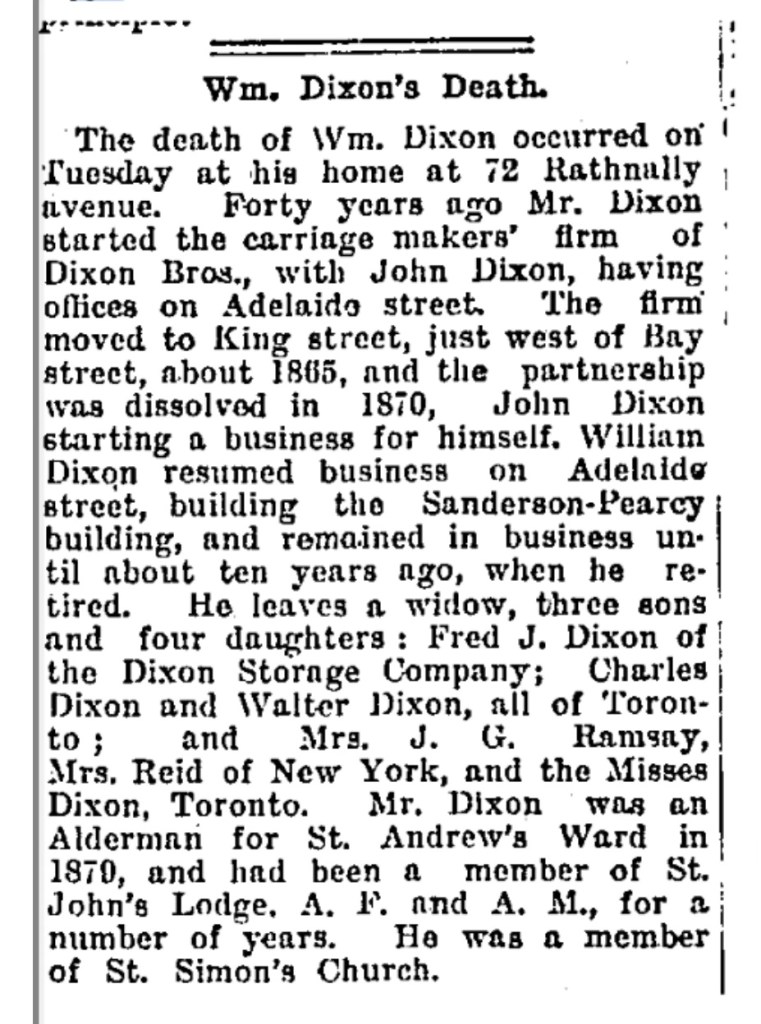

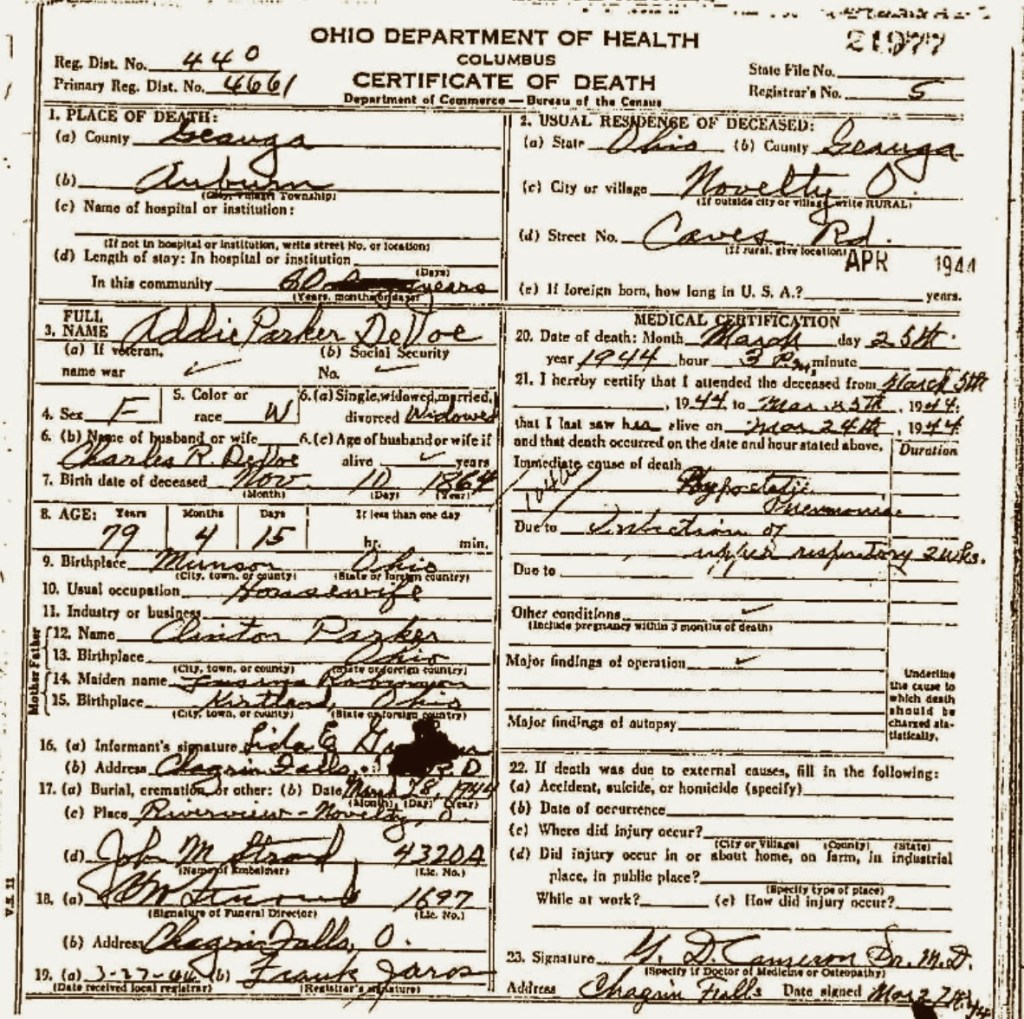

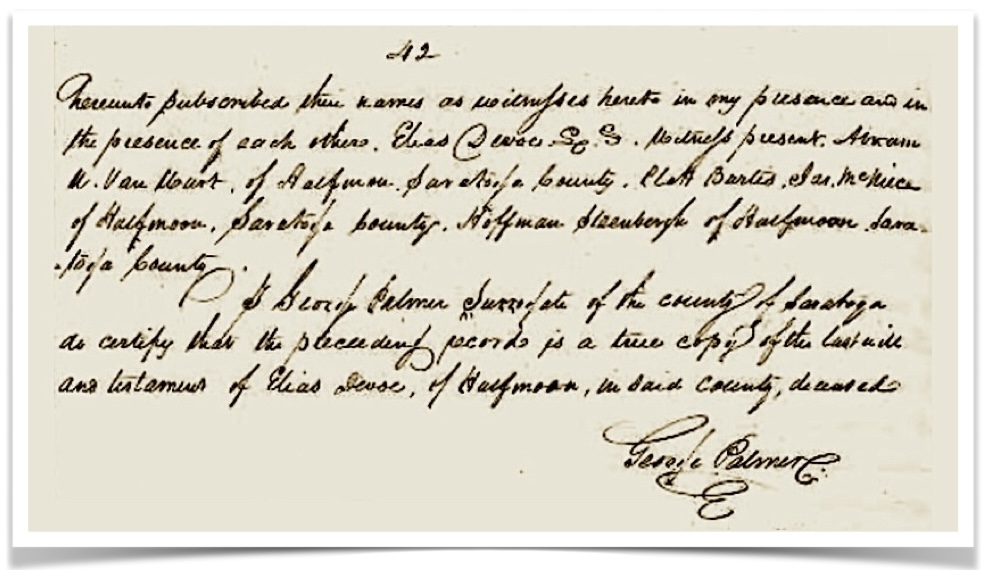

At right: Manuscript of the Lei Áurea from the Brazilian National Archives.

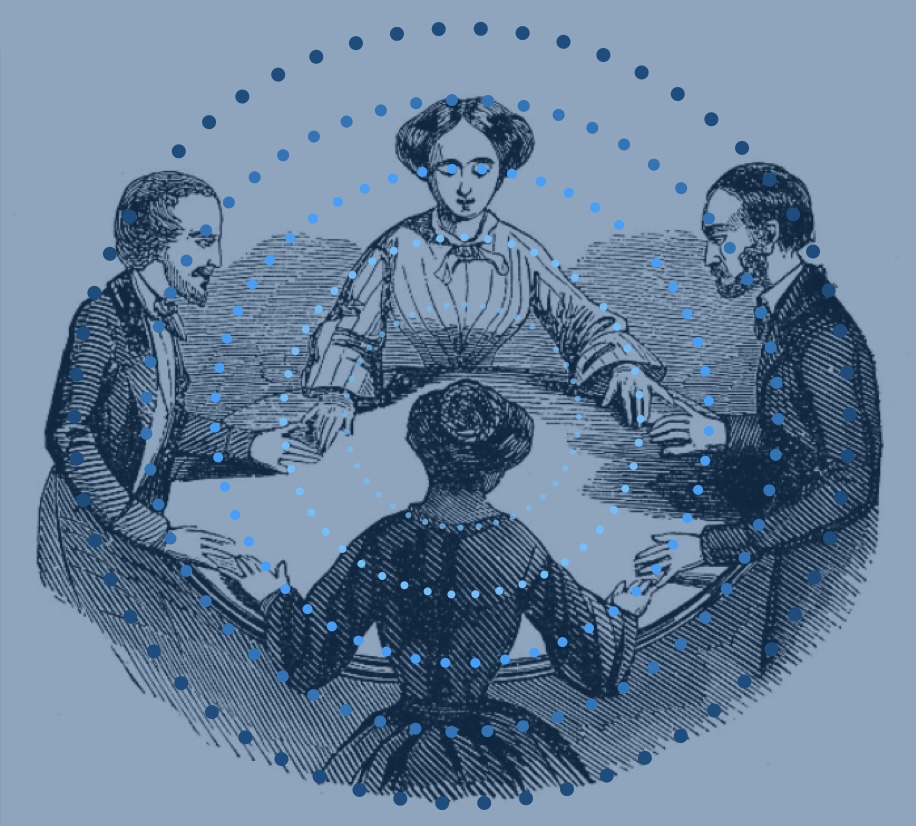

Candomblé and Syncretism

When we lived in Bahia, we would sometimes view portions of Candomblé ceremonies that were held at a place called a terreiro, (a temple or house of worship). These sacred spaces are central to Candomblé, serving as the location for community worship, rituals, and connections with ancestral spirits. We both felt that it was rather remarkable that many different Pai-de-santos (father of the saint) or Mãe-de-santos could look at you and tell you exactly which Orirá looked over you. (And among them in different times and places, they were always consistent).

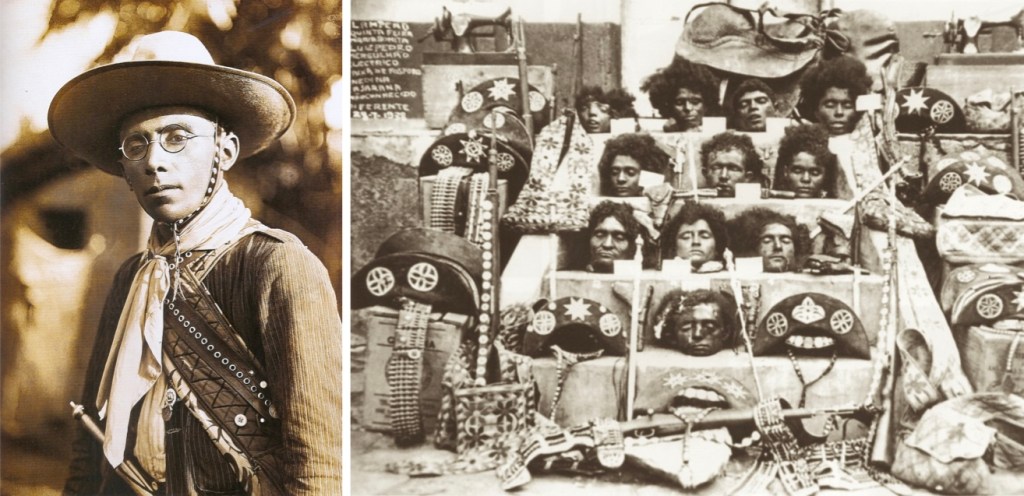

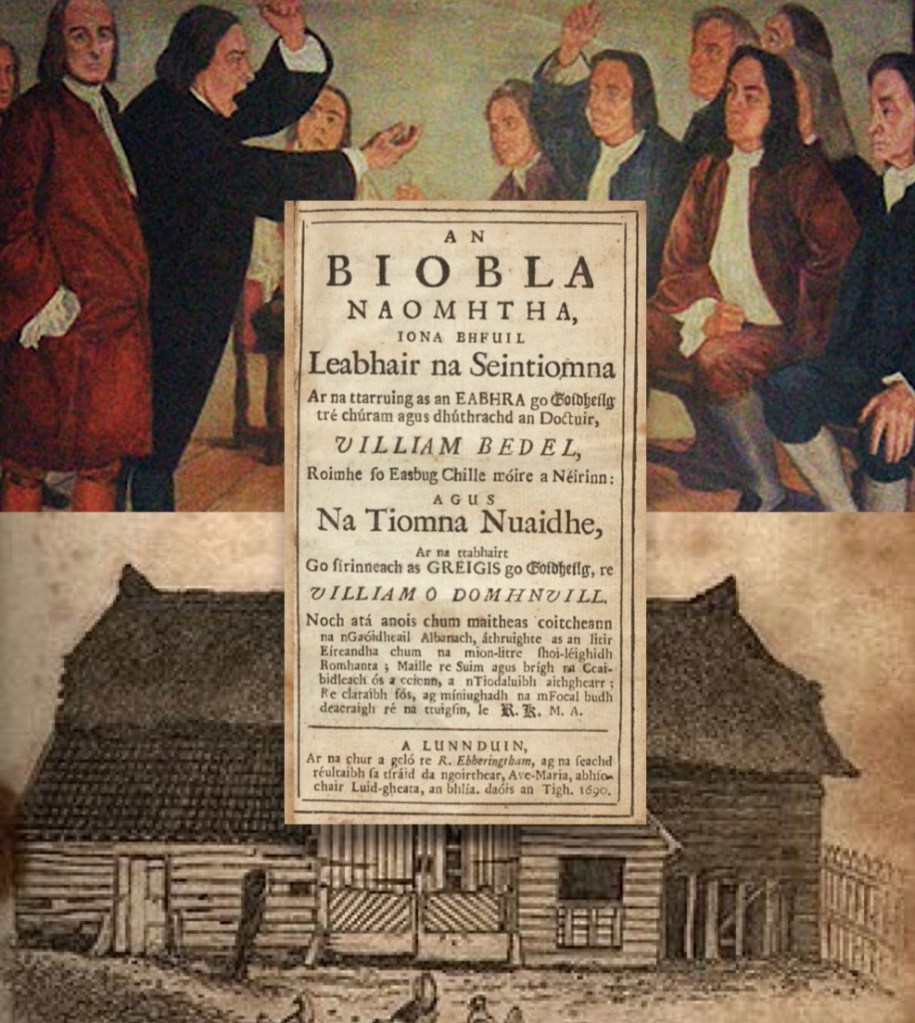

“Candomblé developed among Afro-Brazilian communities amid the Atlantic slave trade of the 16th to 19th centuries. It arose through the blending of the traditional African religions from the Yoruba, Bantu, and Fon people brought to South America, along with Roman Catholicism, especially the Catholic saints. It primarily coalesced in the Bahia region during the 19th century.” (Wikipedia and Altar Gods)

One of the central religious traditions of Candomble is veneration of the Orixas, divine energies associated with different elements of nature. Individuals are believed to identify with one of the Orixas as their tutelary spirit. (Altar Gods)

When these many enslaved peoples arrived in Bahia during this diaspora, they encountered Roman Catholic Portuguese colonialists who then controlled the area. Very cleverly, they maintained their religious affiliations by covertly hiding their own saints who were linked to Catholic saints as a way to preserve African beliefs despite forced religious conversion. This is called syncretism. An example of this is the Orixa Ogun, who stands-in for, Saint George, Saint Sebastian, or Saint Anthony, depending upon your location. Candomblé can be thought of as a non-institutionalized religion in Bahia.

In summary, “Candomblé is a uniquely Afro-Brazilian religion, made possible by mixing African, European, and native Indian traditions in the New World. Candomblé is strongest in Bahia, Brazil, a major port for arriving Africans. Its principal city, Salvador, was the first capital city of Brazil. The first Candomblé temple was built in Salvador in the 19th century after the abolition of slavery.” (Wikipedia) (4)

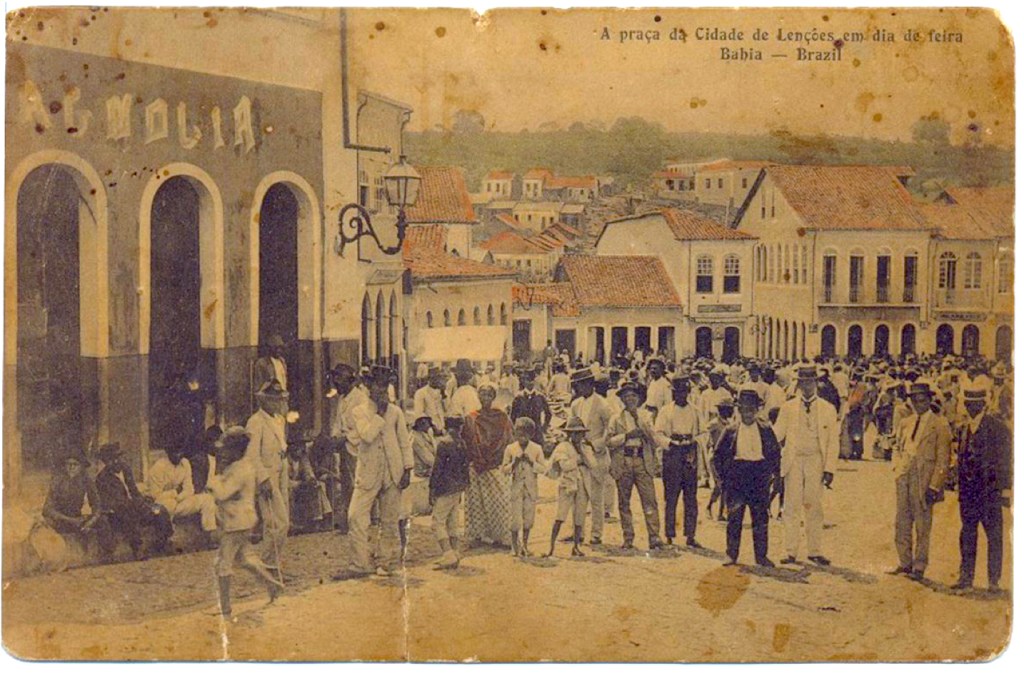

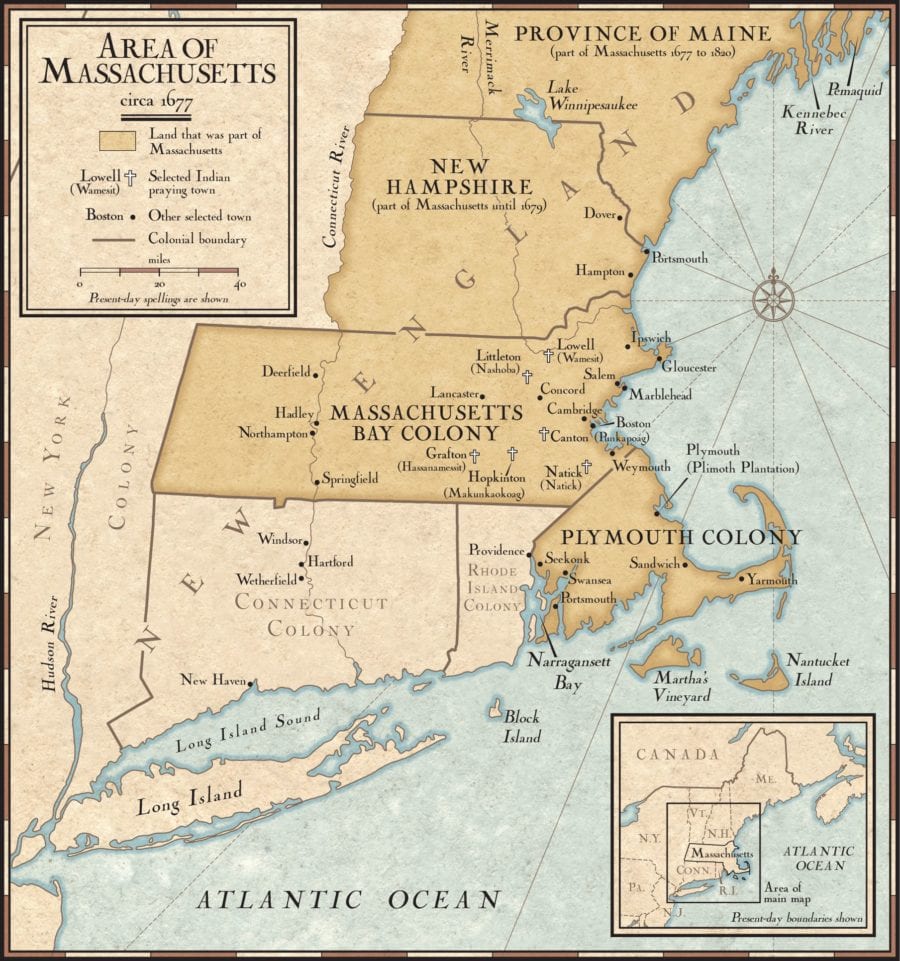

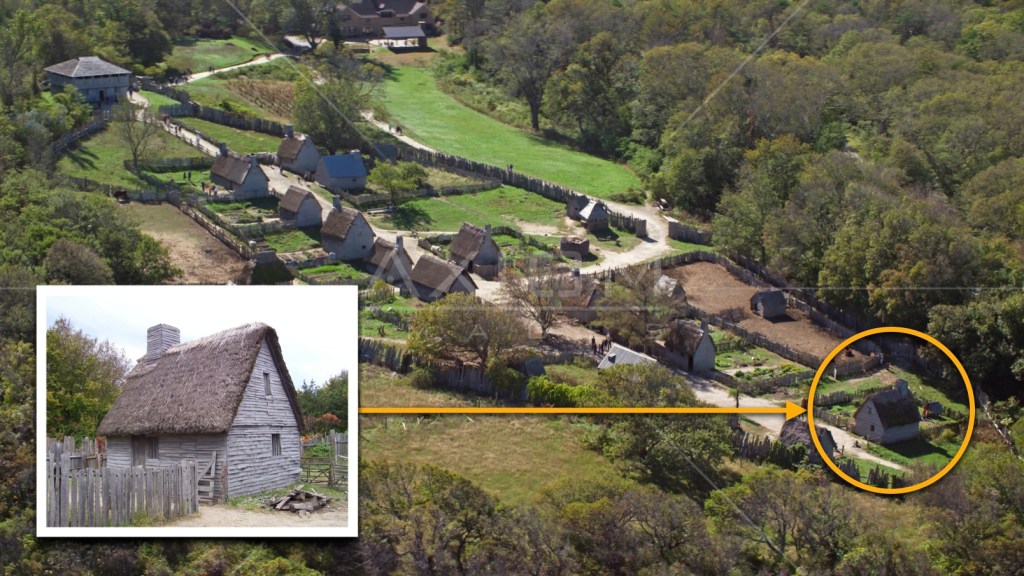

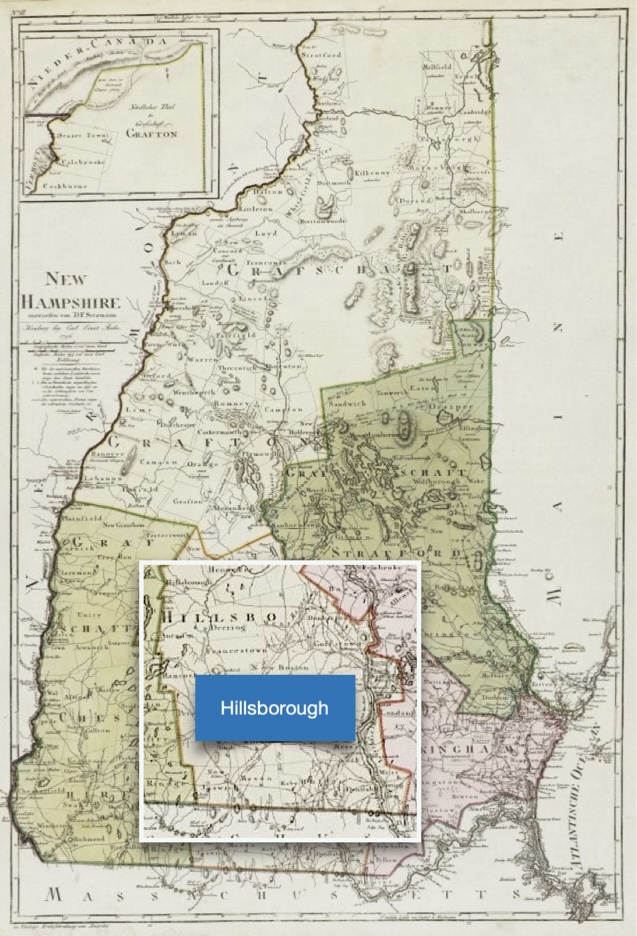

The Oliveira Family of Ubaitaba

Ubaitaba is a small river city found in section of the remaining ancient Atlantic rainforest, in the state of Bahia, between the cities of Salvador and Ilhéus. This region “was formerly inhabited by Indigenous peoples [Tupi] until the arrival of Portuguese colonizers. After contact with the Portuguese and the establishment of the Captaincies of Brazil by King Manuel I of Portugal from 1504 onwards, the municipality’s territory became part of the lands of the Captaincy of São Jorge dos Ilhéus. The village of São Jorge dos Ilhéus was founded in 1536 as Vila de São Jorge dos Ilhéos. The modern name of Ubaitaba is from the Tupi language.

Throughout the 18th century, the Captaincy of São Jorge dos Ilhéus developed, and farms were established along the coast of the vast region. The origin of the village is related to the creation of both the Arraial de Tabocas and the Arraial de Faisqueira farms (in 1783), an area then used for timber extraction, sugar cane, cereal and cocoa cultivation.

On January 28, 1914, a river flood destroyed the Arraial de Tabocas, scattering its population. Coordinated by physician Francisco Xavier de Oliveira, a resident of the village, the victims rebuilt the settlement, rising above the floodwaters. The name chosen was Itapira. [This name was changed to] Ubaitaba, conferred in 1933, a combination of the Indigenous words ‘ubá, meaning small canoe, ‘y,’ meaning river, and ‘taba’ meaning village / city.

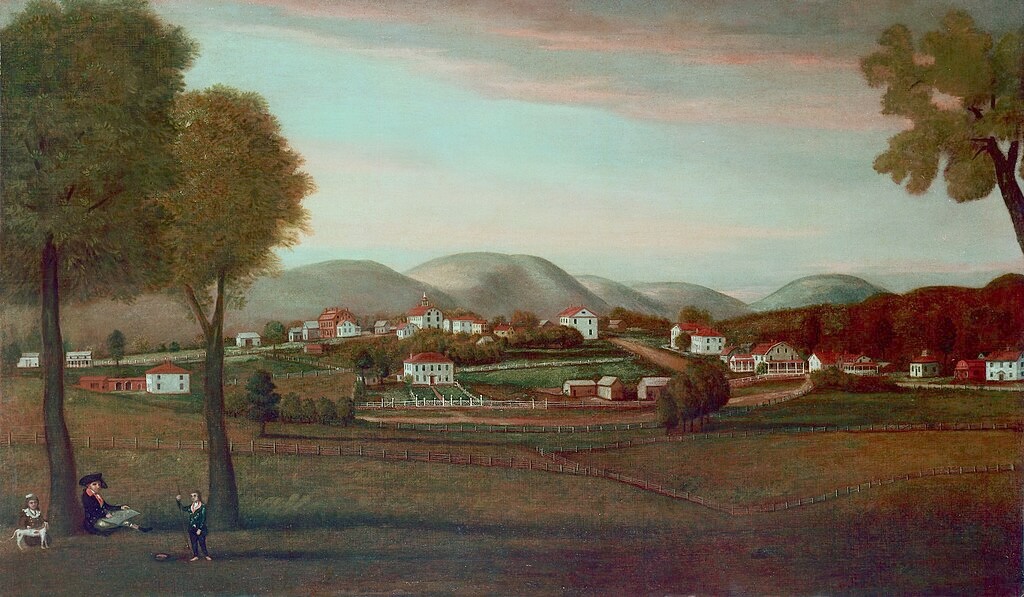

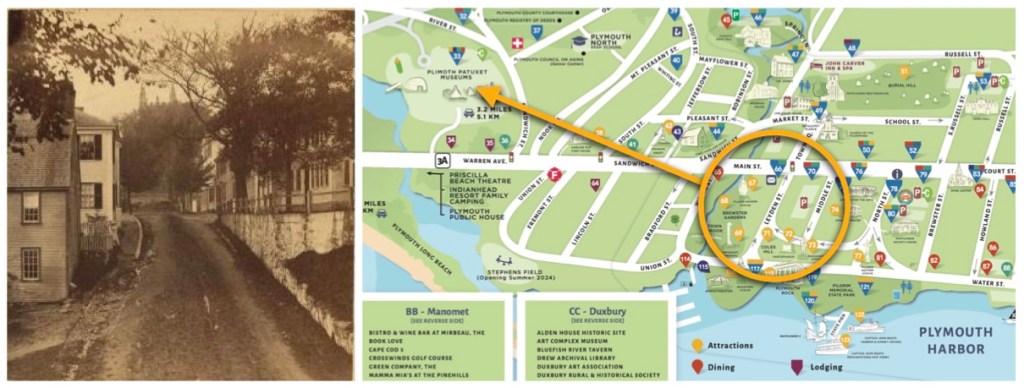

When reviewing the very few historic photographs available of the city, the layout is two parallel roads which run along the river’s edge. Between the two streets is a wide, park-like meridien, with the Catholic Church anchoring one end of town. Shops and stores are one or two stories tall, and facing the street. We provide this description because the Oliveira family ran a general market store in Ubaitaba, of the type then known as a mercearia.

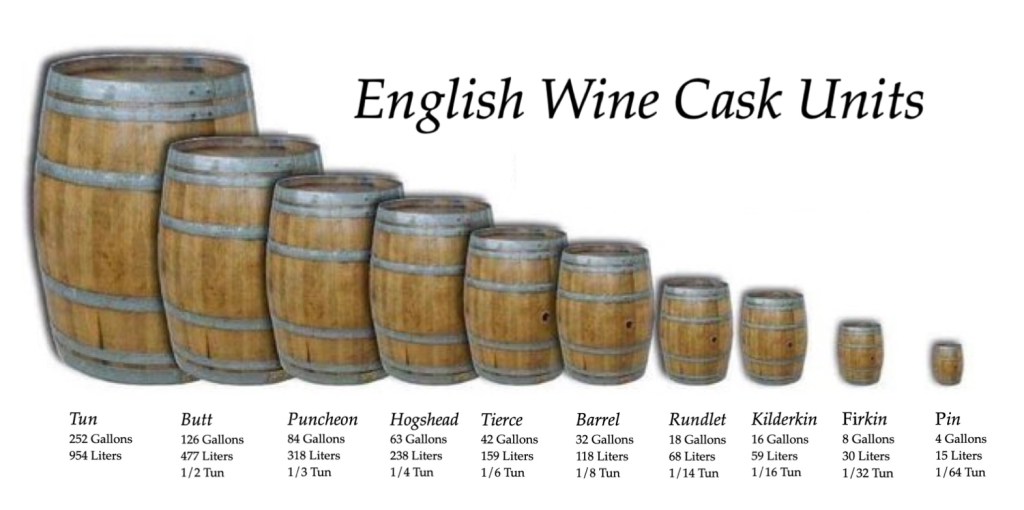

Before the rise of large retail chains, mercerias gerais (general stores) served as essential neighborhood stores where people could buy a range of everyday products, acting as a central point in local communities. They sold a wide variety of basic and imported goods, including staples like rice, beans, and sugar, along with everyday essentials like soap and matches, and a selection of imported foods and liquors. They also offered locally made products such as coffee, cheese, and fruits.

Some rare mercearias still exist to this day, but that particular evocative name has given way to the rather bland and universal name of mini-market. (Think lottery tickets, cigarettes, a carton of milk, and perhaps some chips, or donuts). In this modern Walmart era in which we live, very few places still exist in local communities, where you can walk into a small family store and everyone knows your name.

For the de Oliveira family…

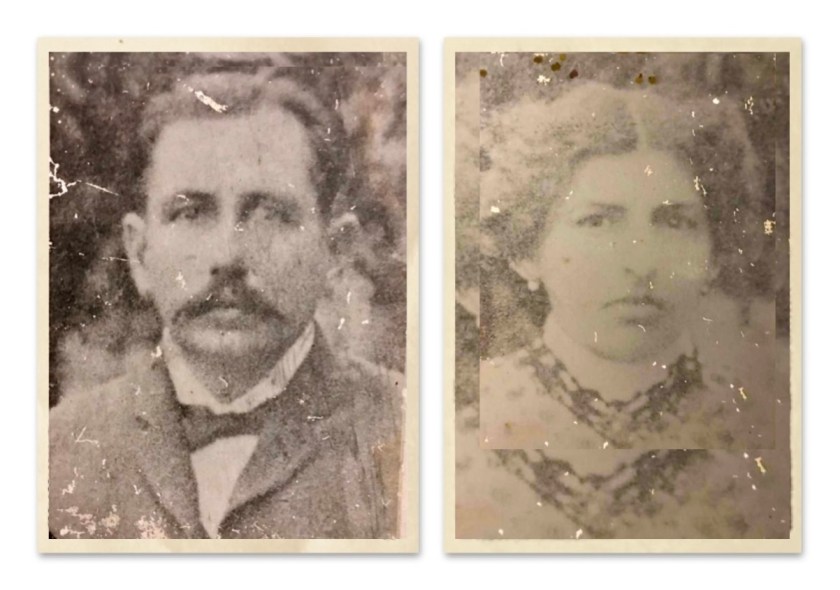

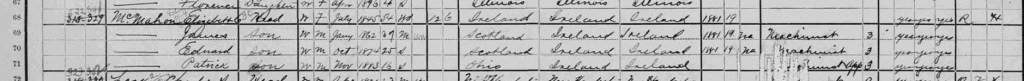

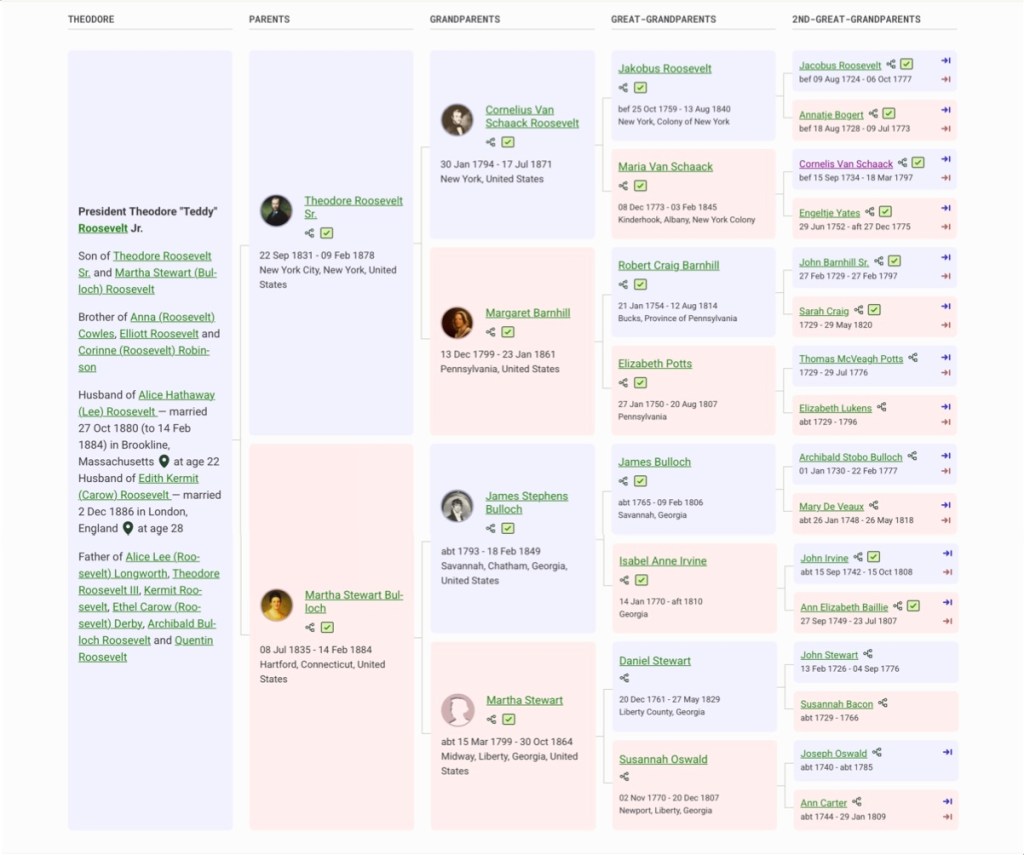

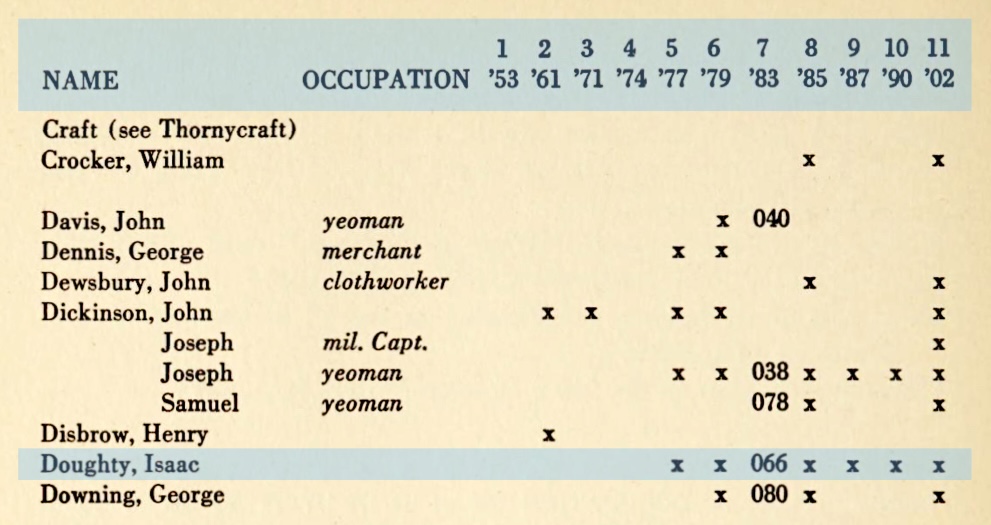

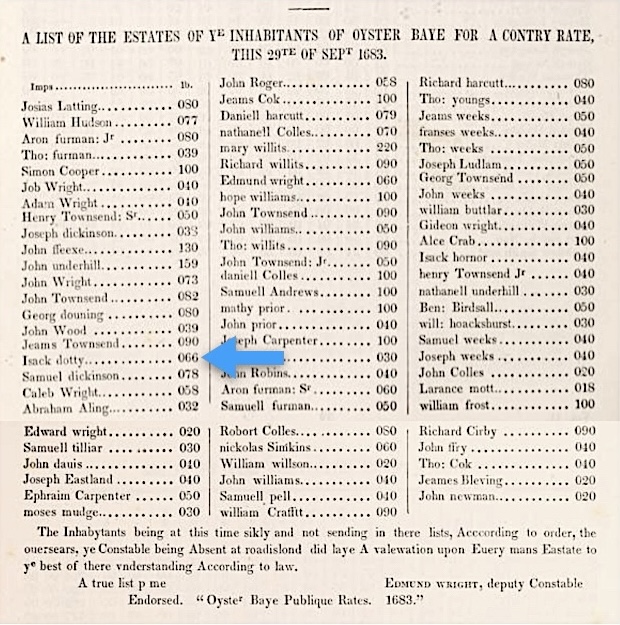

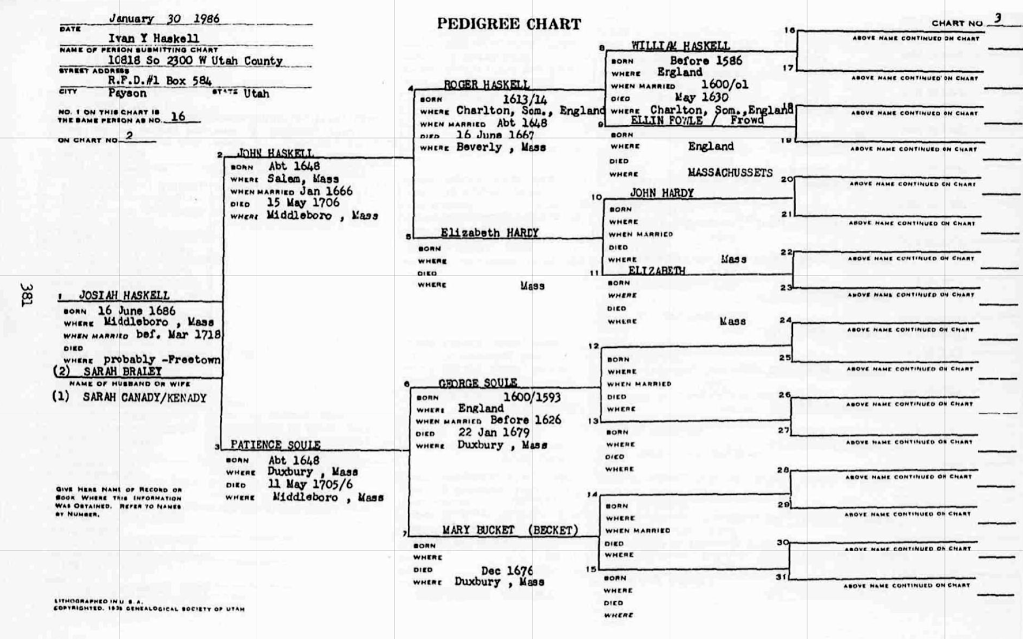

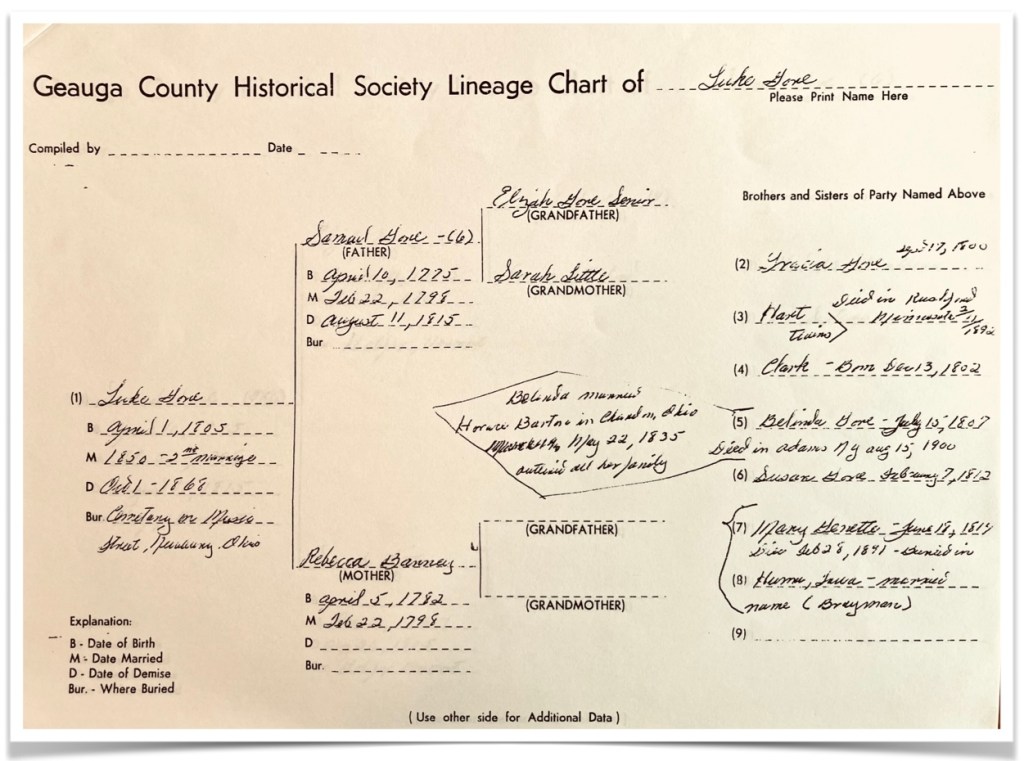

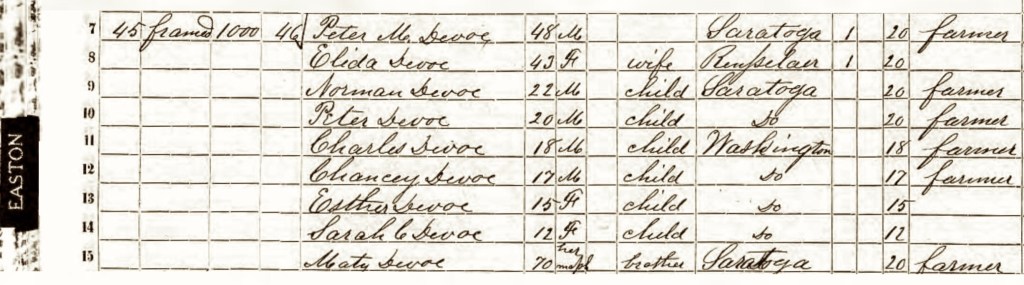

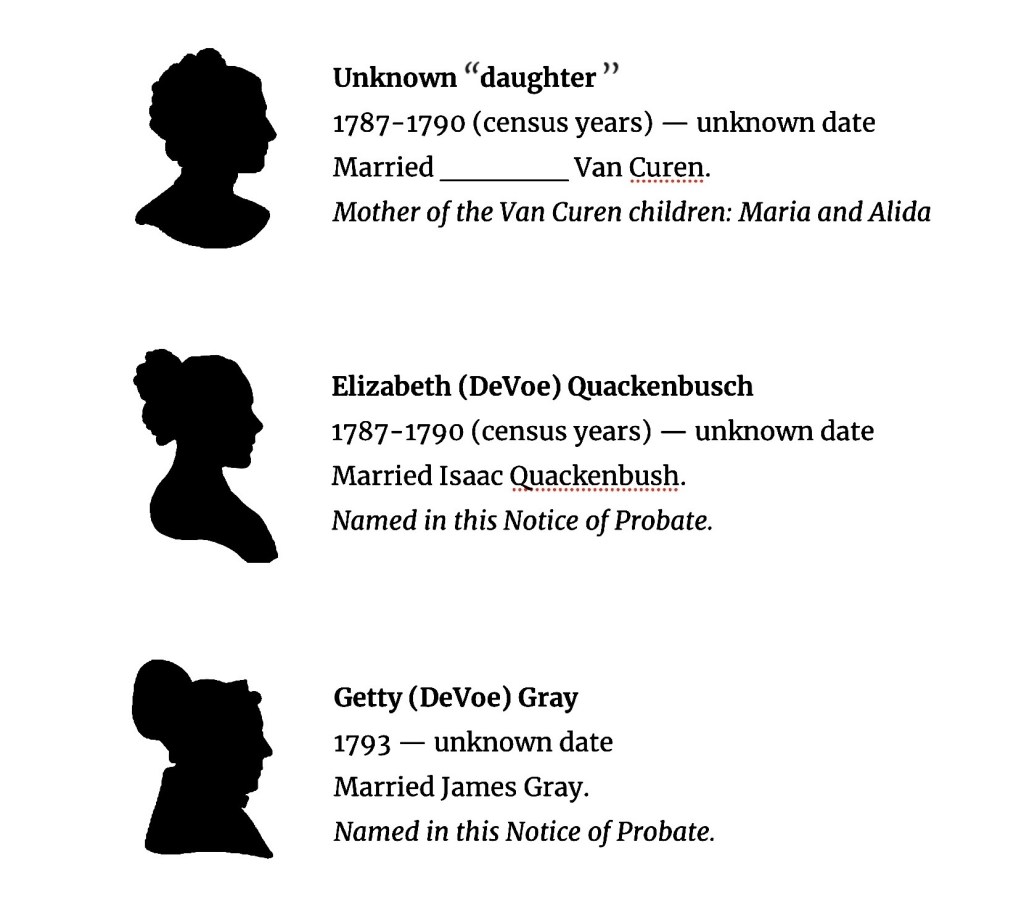

We can begin with, Manoel Celestino de Oliveira, born (likely) in Brazil. He married Rita Celestino de Oliveira. They had a son, who is named —

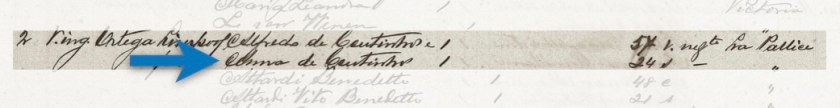

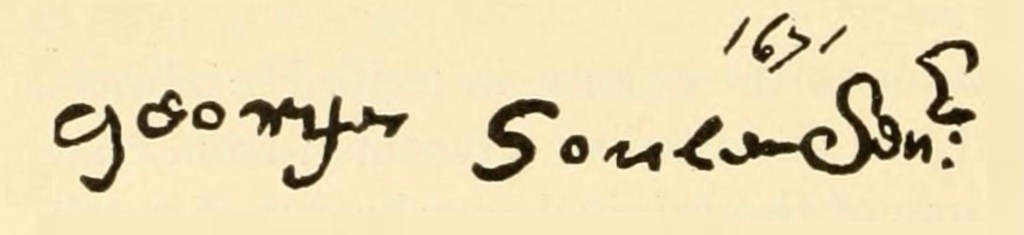

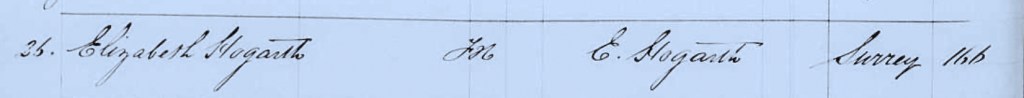

João Celestino de Oliveira, born November 6, 1890 — in Maceió, Alagoas (state) died November 25, 1968, in Ubaitaba. He was married two times: first to Eufrosina Souza Oliveira, until her death before 1925. They had one child.

Second, he married Maria de Almeida in 1925. She was born on March 20, 1900 in Maracás — died October 5, 1968, in Ubaitaba. They had four more children.

Maria de Almeida’s parents were: Cândido Olegário de Almeida and Balbina Olegário.

Together, João Celestino de Oliveira and Maria de Almeida raised 5 children. All births and deaths are in Bahia, Brazil, unless noted otherwise:

- Agostinho Celestino de Oliveira, born August 13, 1919 — died April 12, 1983.

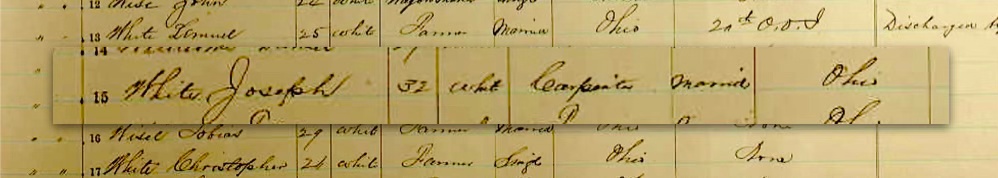

(His birth mother was first wife Eufrosina Souza Oliveira). He married Ana Eusátquio de Souza on April 24, 1944. - Lindaura de Almeida (Oliveira) Coutinho, born October 24, 1927 in Ubaitaba — died June 19, 2020 in Salvador.

(Lindaura carries the family line forward. See her spouse and children below). - Laura de Almeida (Oliveira) Motta, born March 27, 1929. She married Raynelde Dantas Motta, on March 30, 1949.

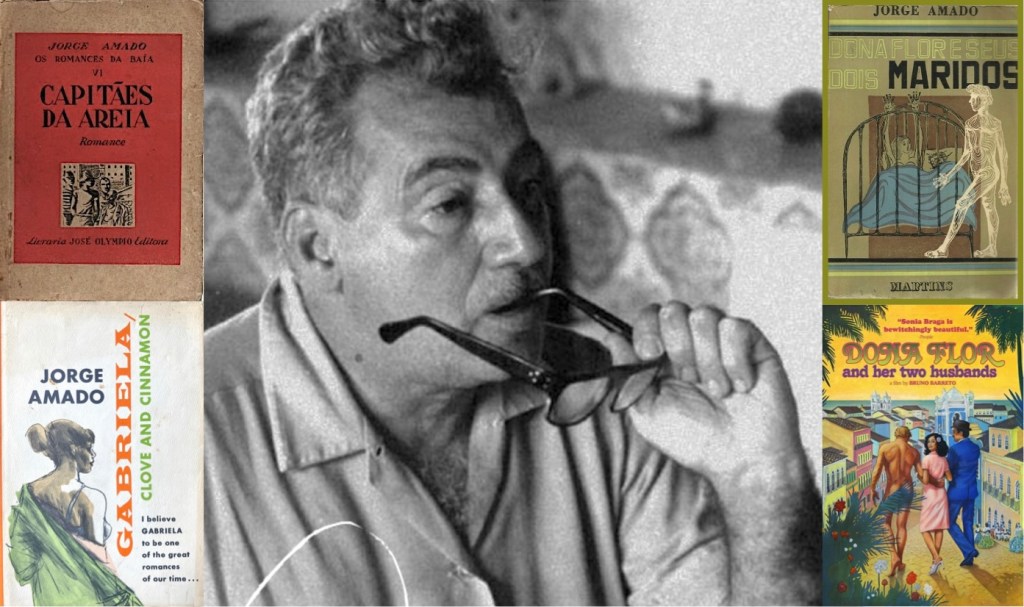

- José Celestino de Oliveira, born December 20, 1937 — died 1992. He married Nidia Maria Amado de Oliveira in May 1968.

She was a cousin of the beloved Brazilian novelist Jorge Amado, (see footnotes). - Maria Lourdes de Almeida (Oliveira) Cunha, born November 11, 1938. She married Humberto Olegário da Cunha on December 28, 1965. (5)

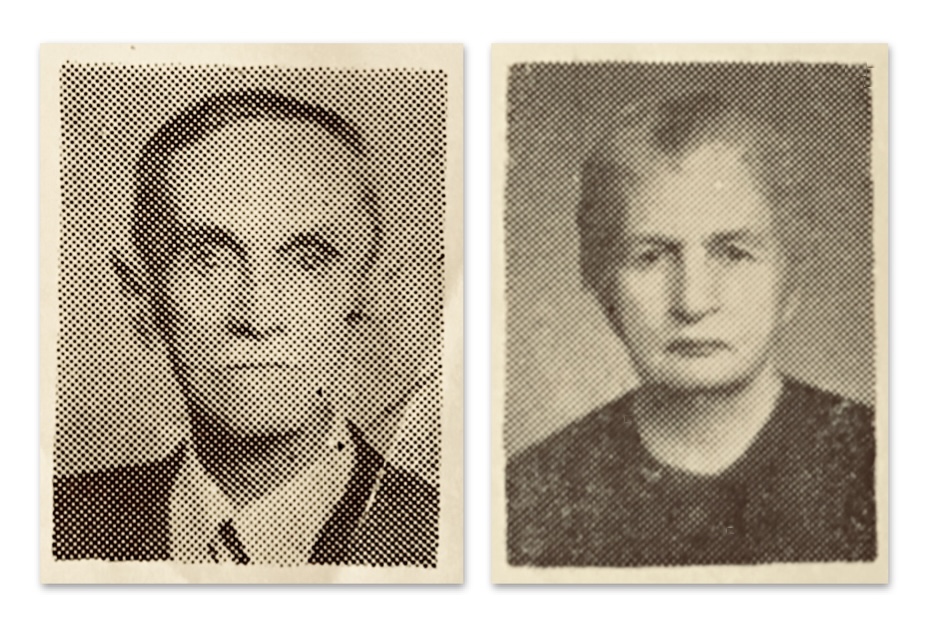

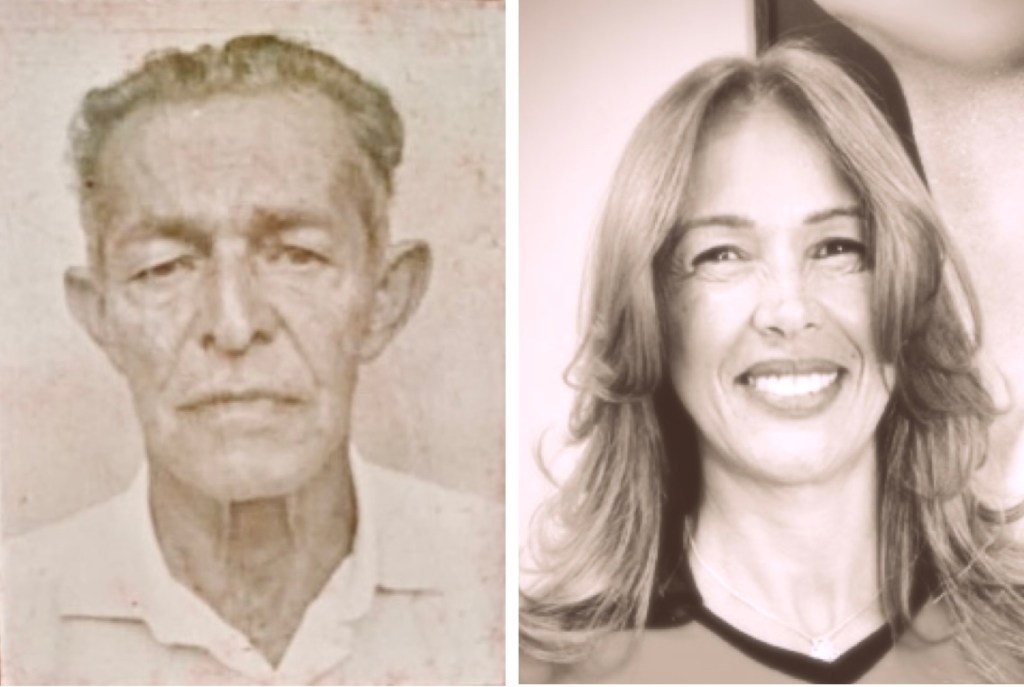

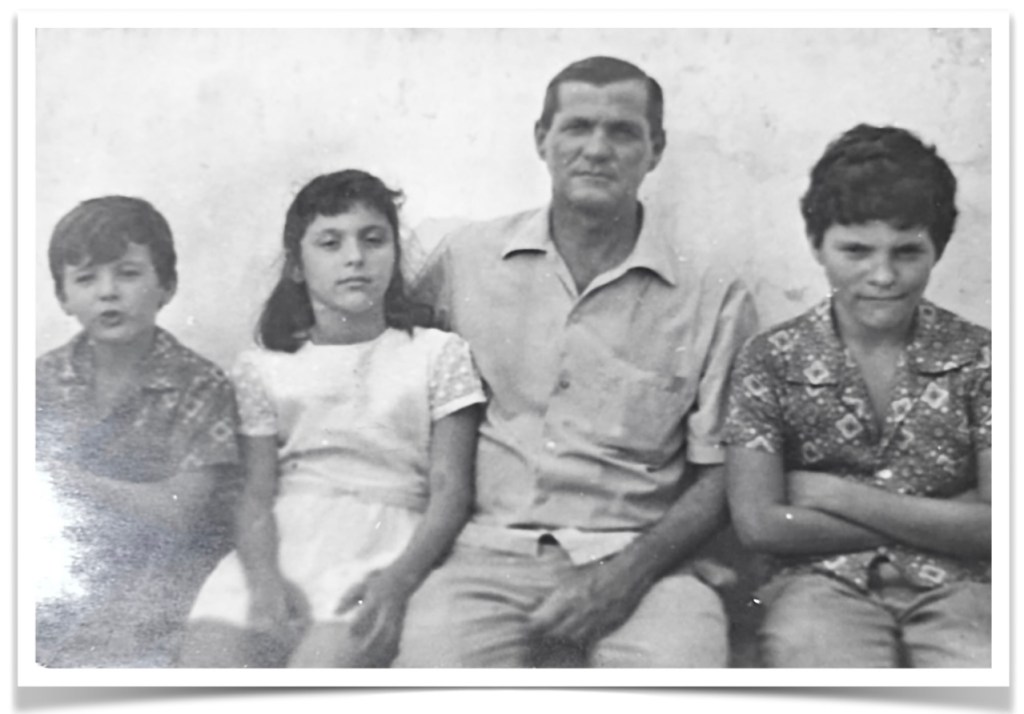

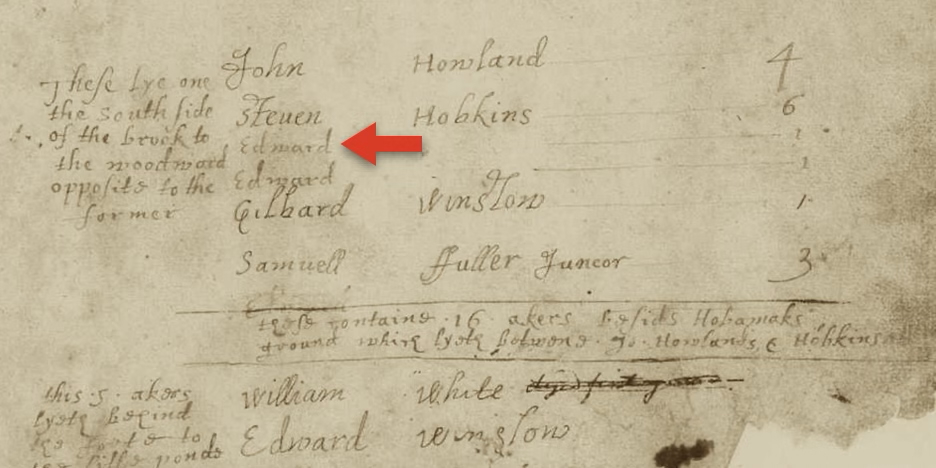

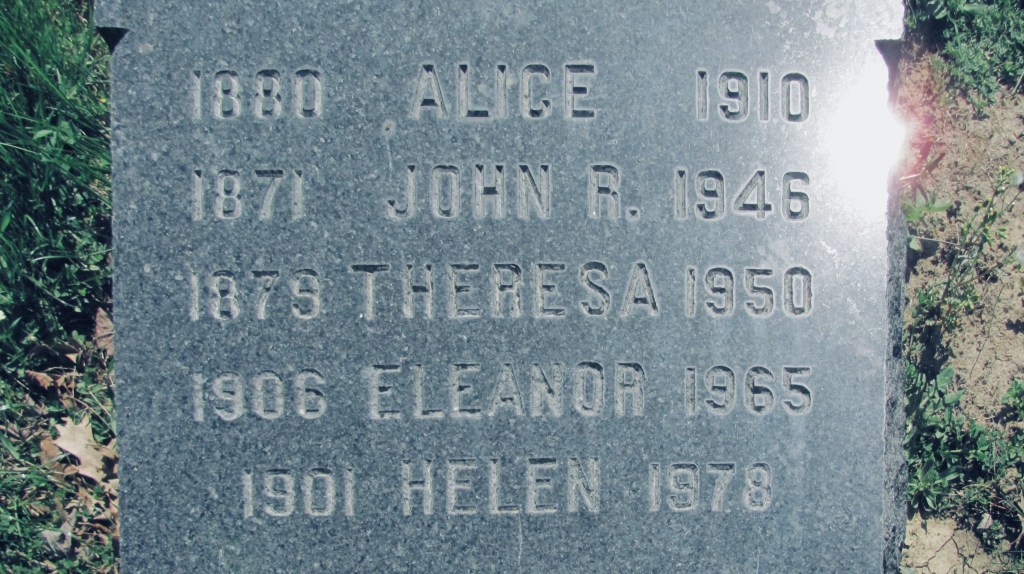

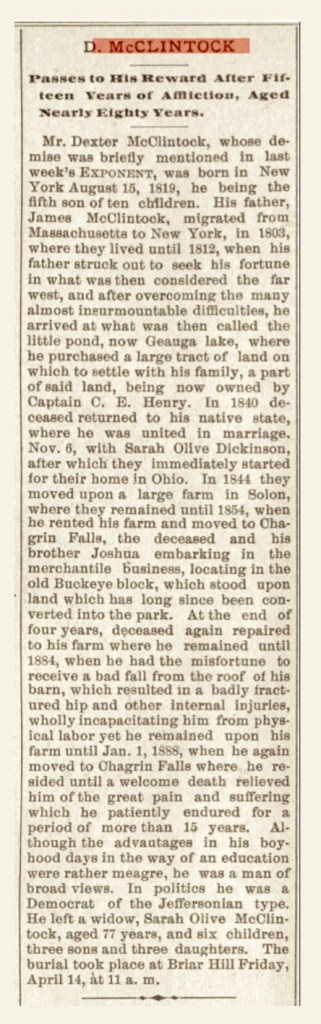

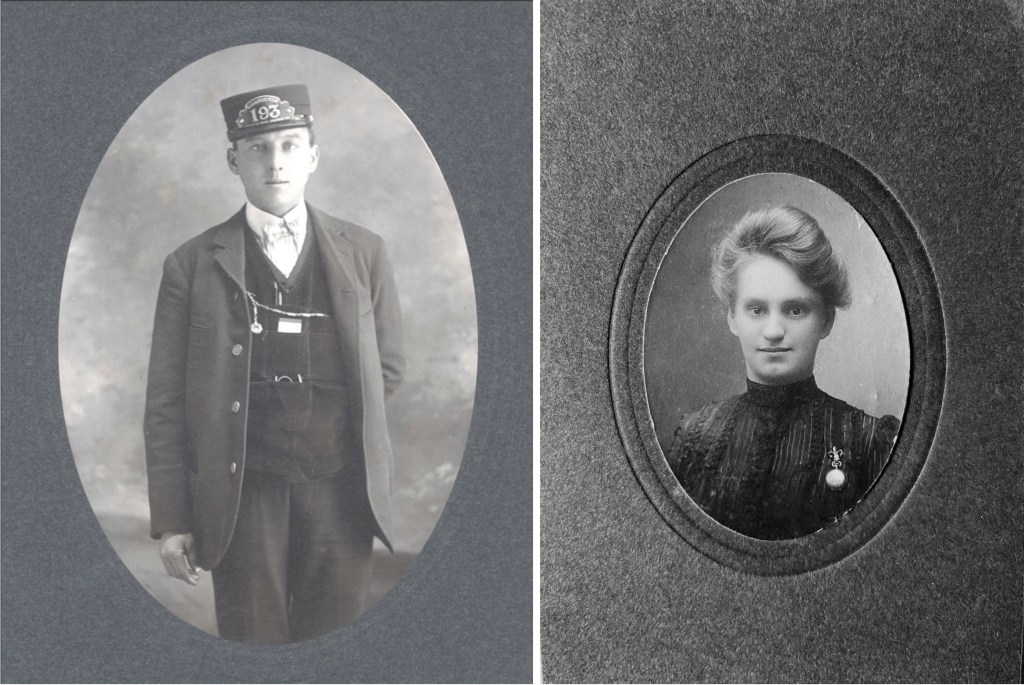

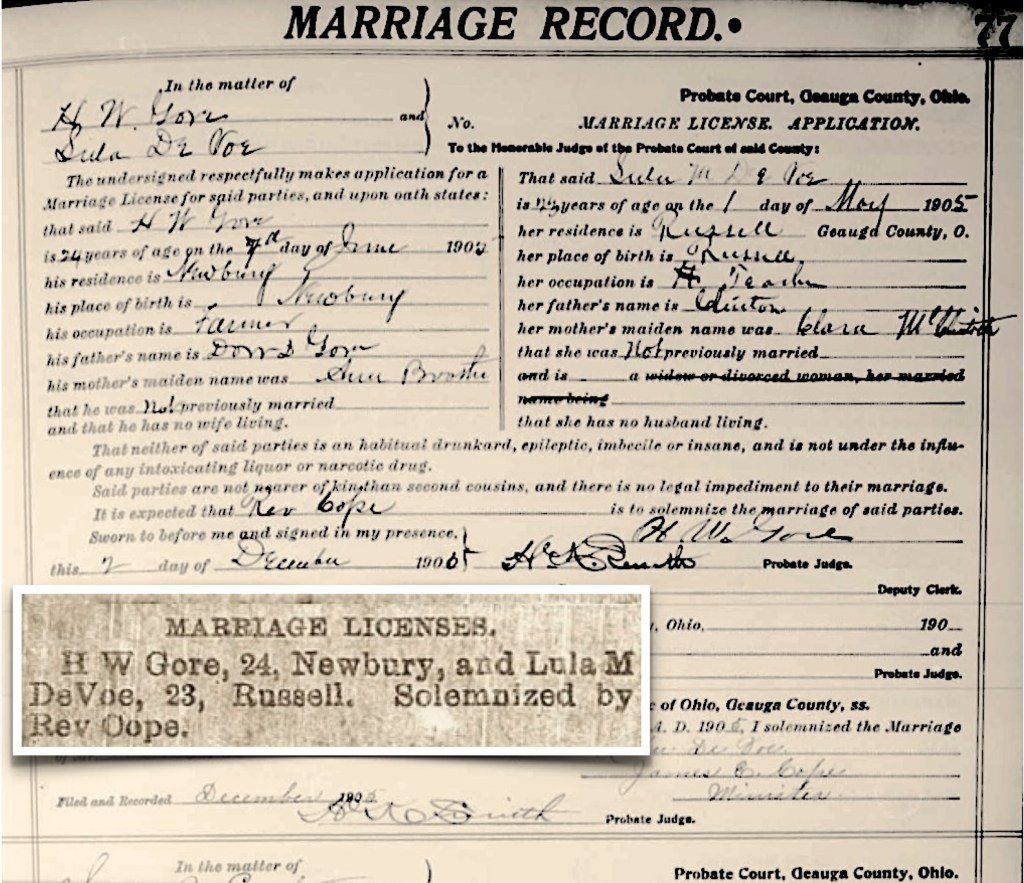

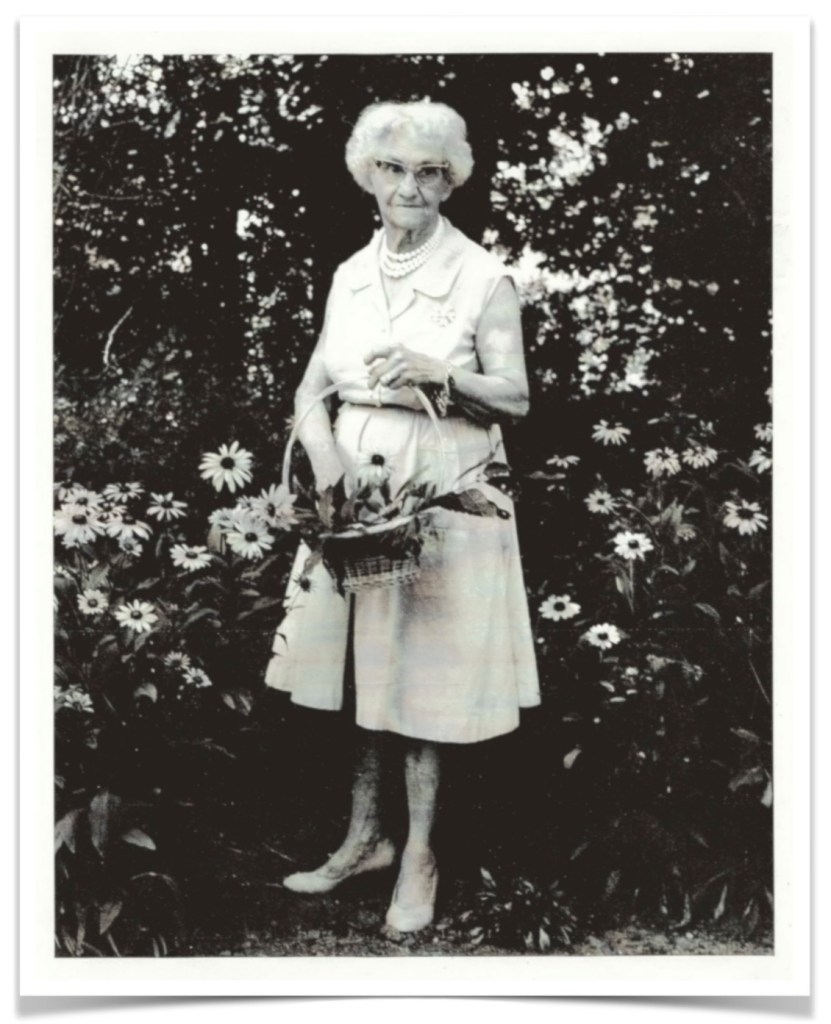

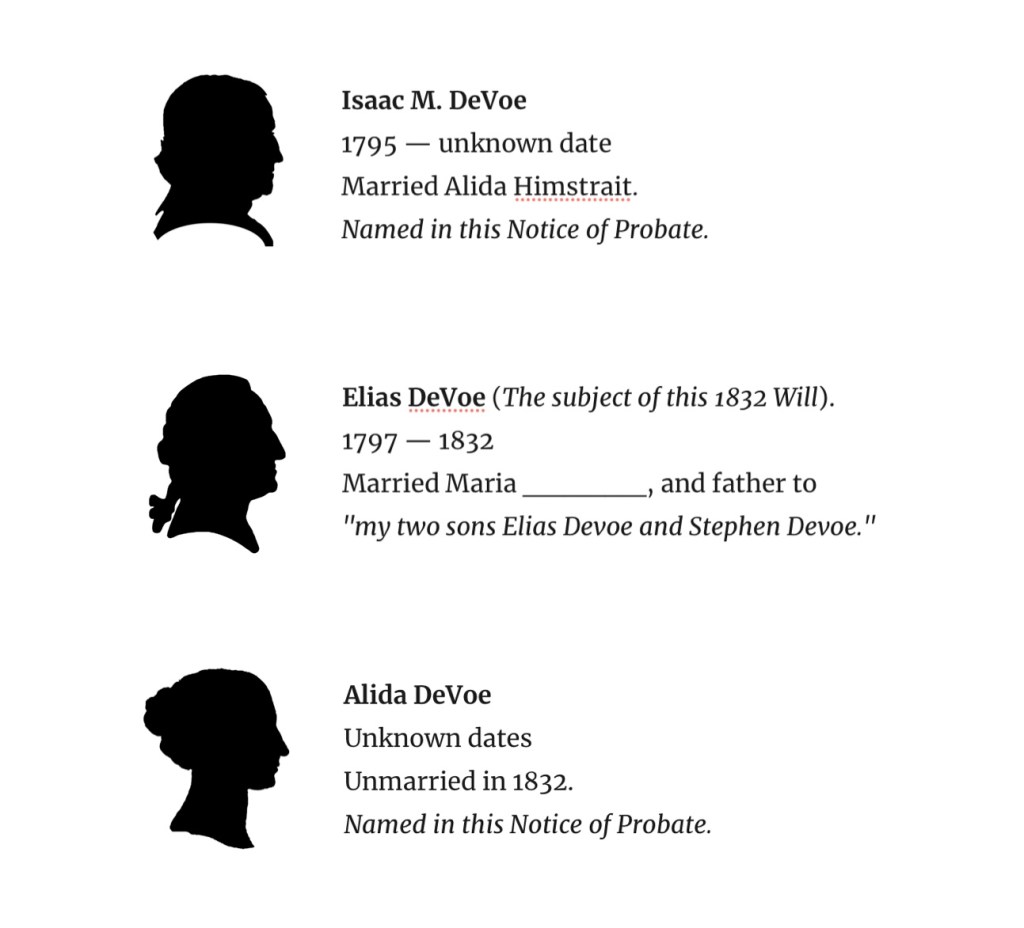

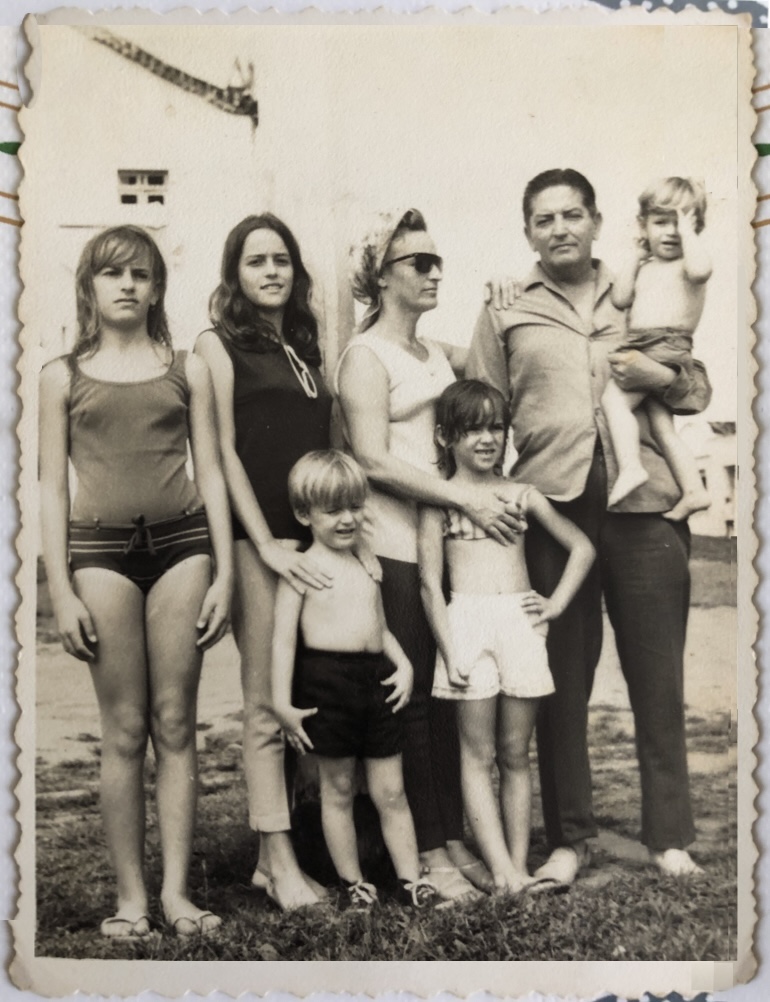

Lindaura Almeida (Oliveira) Coutinho, circa 1950s.

(Family photographs).

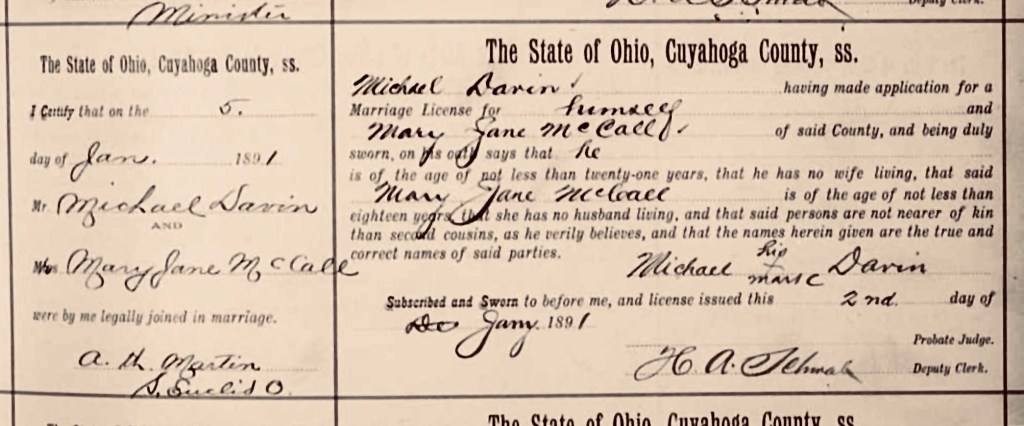

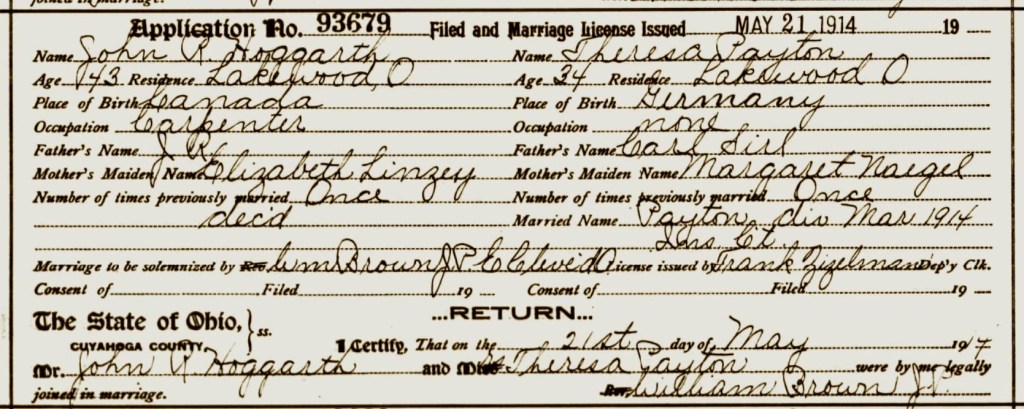

“You can’t imagine how much I’ve missed you…”

Before they were married, Paulo and Lindaura corresponded via letters for about two years before becoming engaged in September 1950. (At that time, letters were the only way they could communicate. Home telephones were still rather new and quite expensive, in the Brazil of that that era). None of those courtship letters have survived, but a few others have. When we looked at them we noted the degree of tenderness with which he still wrote to his wife Lindaura, even many years after they were married. In a 1968 letter (which we have placed the in the footnotes), we read these words —

April 11, 1968

My dear Lindaura,

Wishing you health together with our dear children.

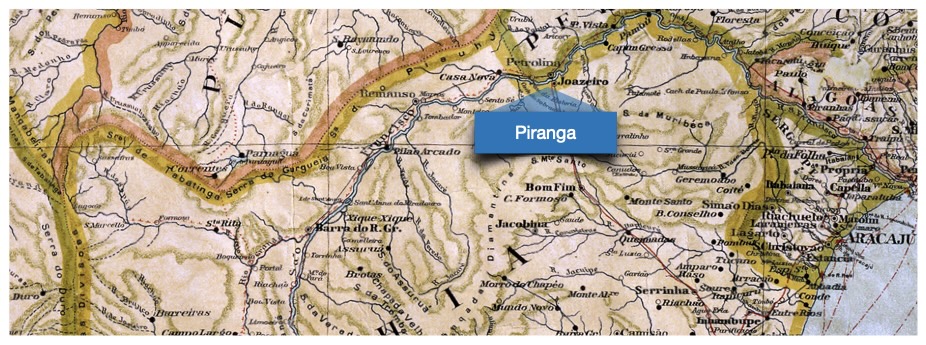

I’m arranging things so that you can come here in the beginning of May. Rivaldo has found a house in Piranga, but he has to make major repairs. I won’t be paying rent, nor for any repairs.

I think that our little ones won’t be too unfamiliar with the climate in Piranga. Soon, I’ll write you a more detailed letter. You can’t imagine how much I’ve missed you. Many kisses to our children. A melancholic hug from your Paulo.

PS: The bonus will be worth it. NBR 500.00. If the “Ritom” truck doesn’t arrive by the 17th of this month, I’ll send Maria Celeste’s dresses by plane.

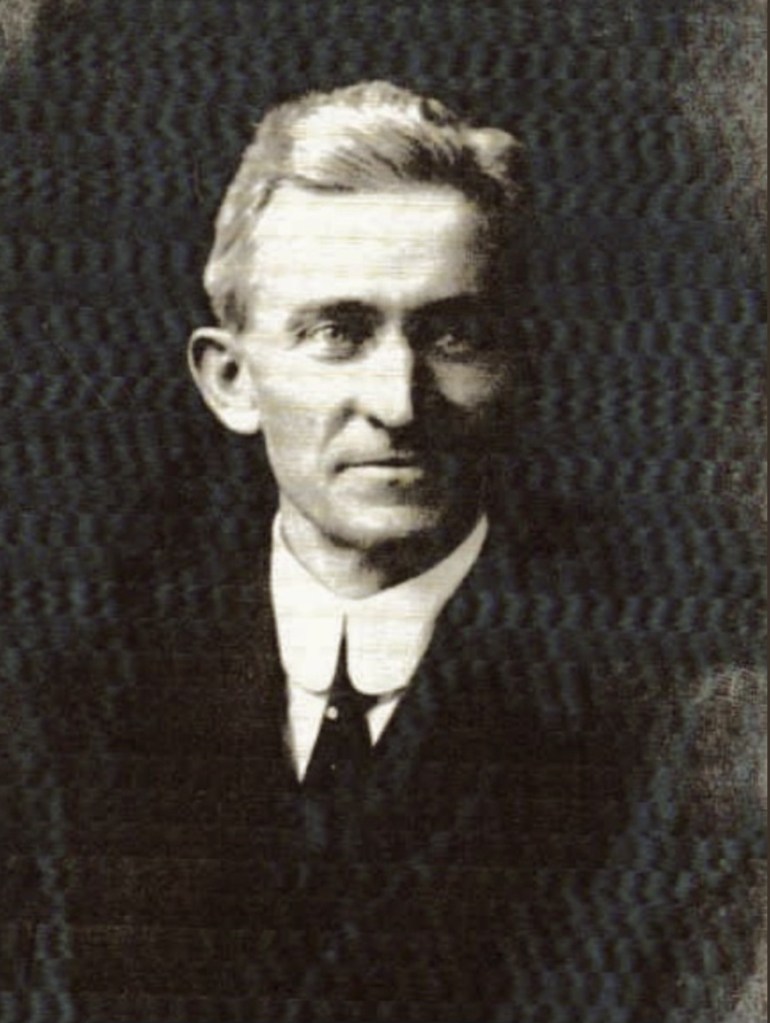

Paulo de Azevêdo Coutinho, born June 29, 1919 in Lençóis — died November 28, 1990 in Salvador. He married Lindaura Almeida de Oliveira on March 19, 1952 in Ubaitaba. She was born October 24, 1927 in Ubaitaba — died June 19, 2020 in Salvador.

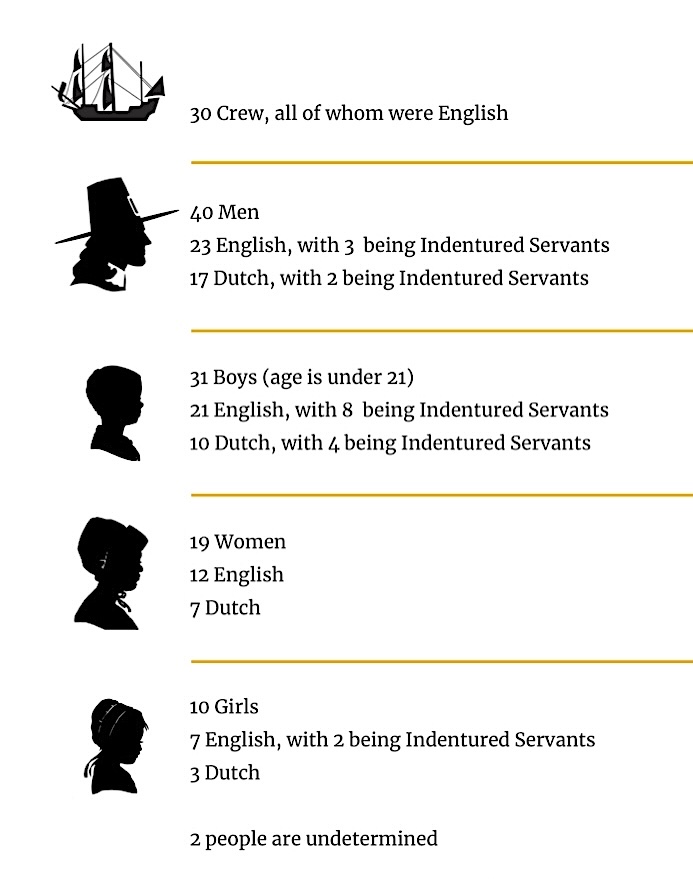

They had five children together, as follows below. All births and deaths are in Bahia, Brazil, unless otherwise noted:

- Maria Celeste Oliveira Coutinho, born July 14, 1953 in Salvador. She married Bernardino Dantas de Santana on July 28, 1989, — (ends) unknown date.

- Maria Angela Oliveira (Coutinho) Martins Bass, born April 11, 1955 in Salvador. She married two times, first to Antonio Martins, Jr., 1985 — (ends) before 2002. She married second Robert Bass, 2002 — 2010, (his death). He died in Sarasota County, Florida, United States.

- Maria Cristina Oliveira (Coutinho) Pinheiro, born May 27, 1961 in Ilhéus. She married Antonio Carlos Marques Pinheiro on September 17, 1983. They had two children.

- Paulo Emilio Oliveira Coutinho, born September 17, 1963 in Ilhéus. He married once, first to Marizela Cardoso Sales, 1991 — (ends) before 2023. They had two children. Second, he was domestic-partnered to Sonia Alves Silva Chagas, in 2023. They have one child.

- Leandro José Oliveira Coutinho, born September 30, 1965 in Ilhéus. He married Thomas Harley Bond on June 26, 2008.

Prior to knowing Lindaura Almeida Oliveira, Paulo de Azevêdo Coutinho had a previous relationship with a woman named Zulmira Silva. Even though they never married, and the fact that she passed on in 1952, from this union there were two children who were half-siblings of the (above) family. Paulo was then the father to seven children.

- Sonia Maria De Azevêdo (Coutinho) Costa, born November 5, 1942, in Salvador. She married Jorge Augusto de Oliveira Costa in 1969. They had two children.

- Newton de Azevêdo Coutinho, born September 25, 1944 — died May 27, 2000, both in Salvador. He married Titê _______ in 1971. They had one child. (6)

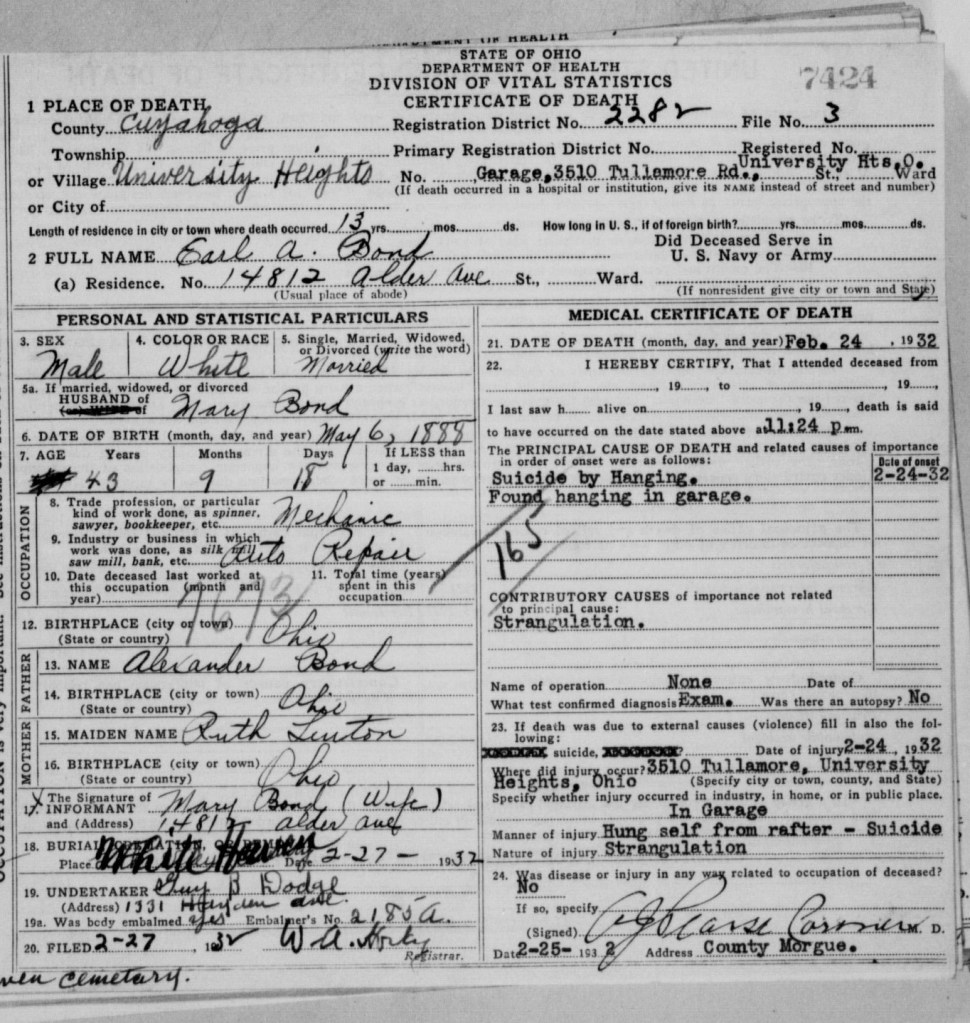

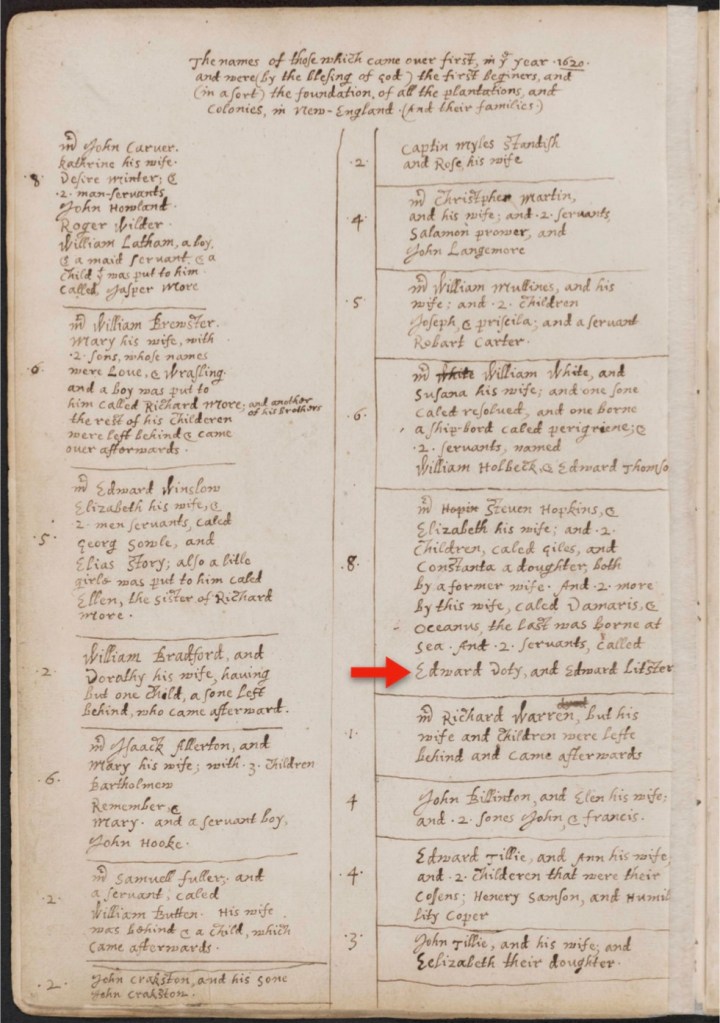

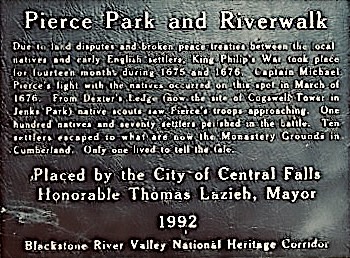

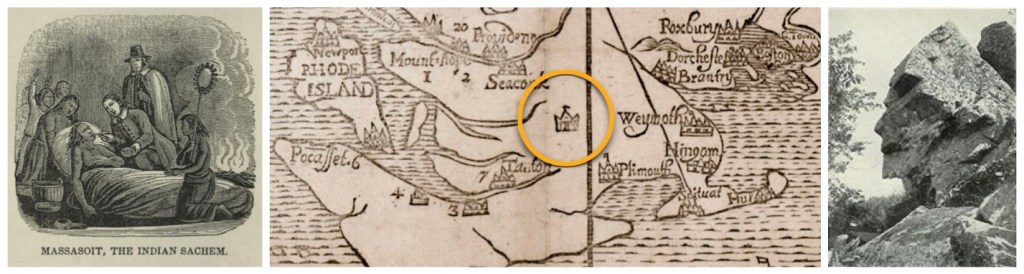

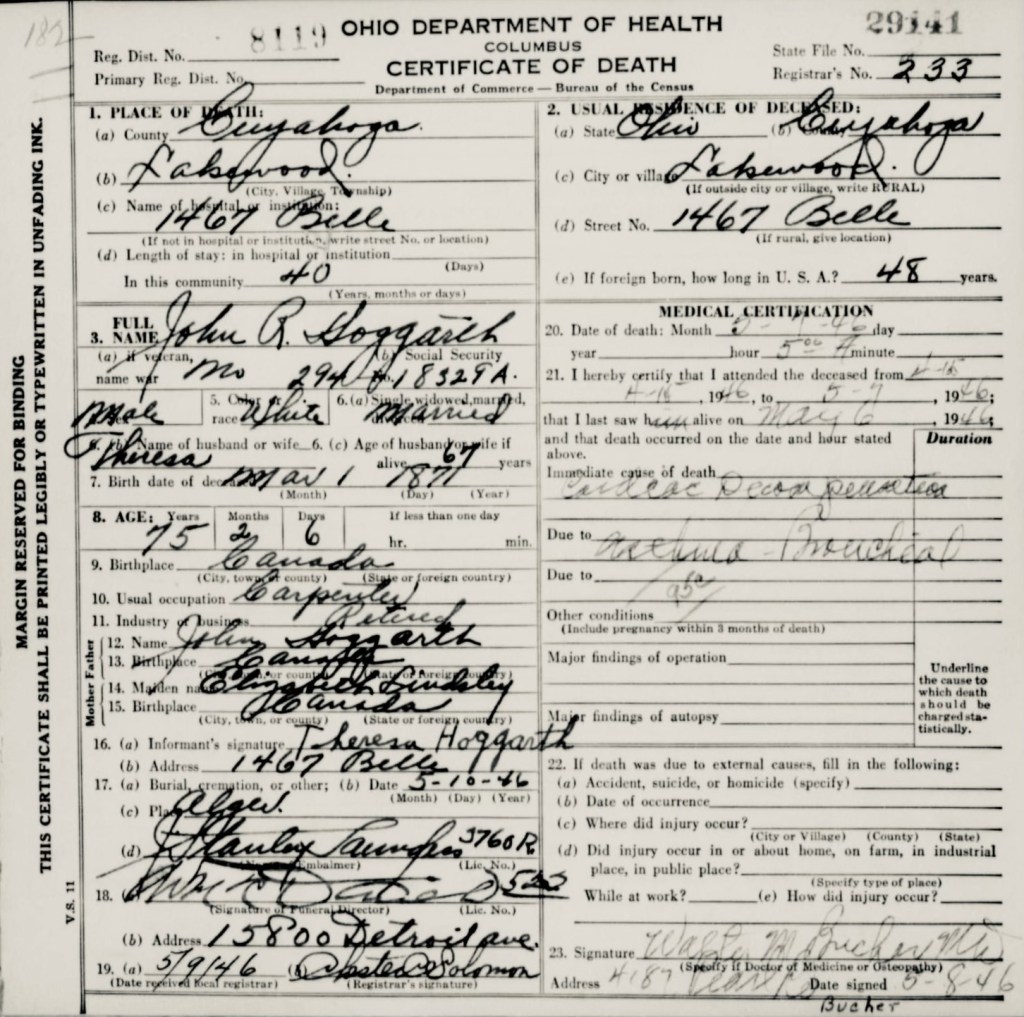

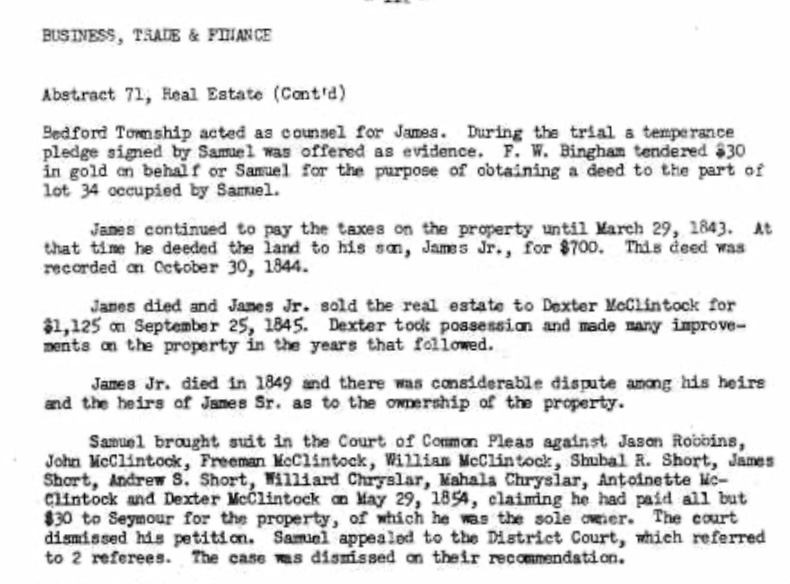

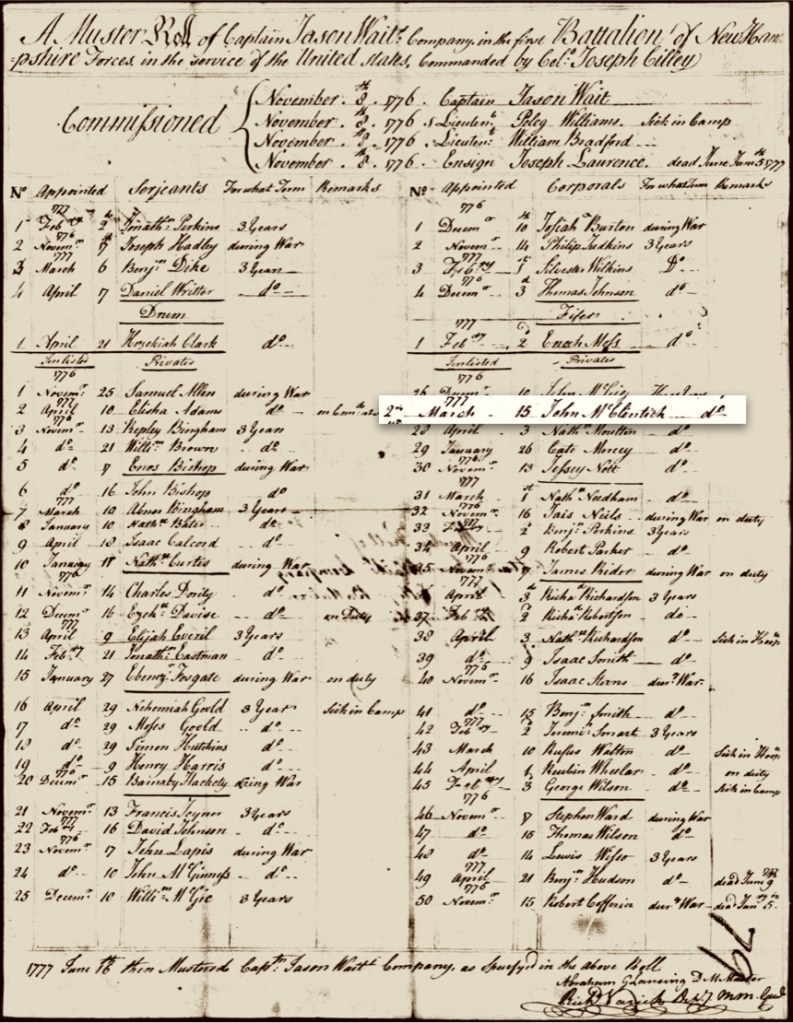

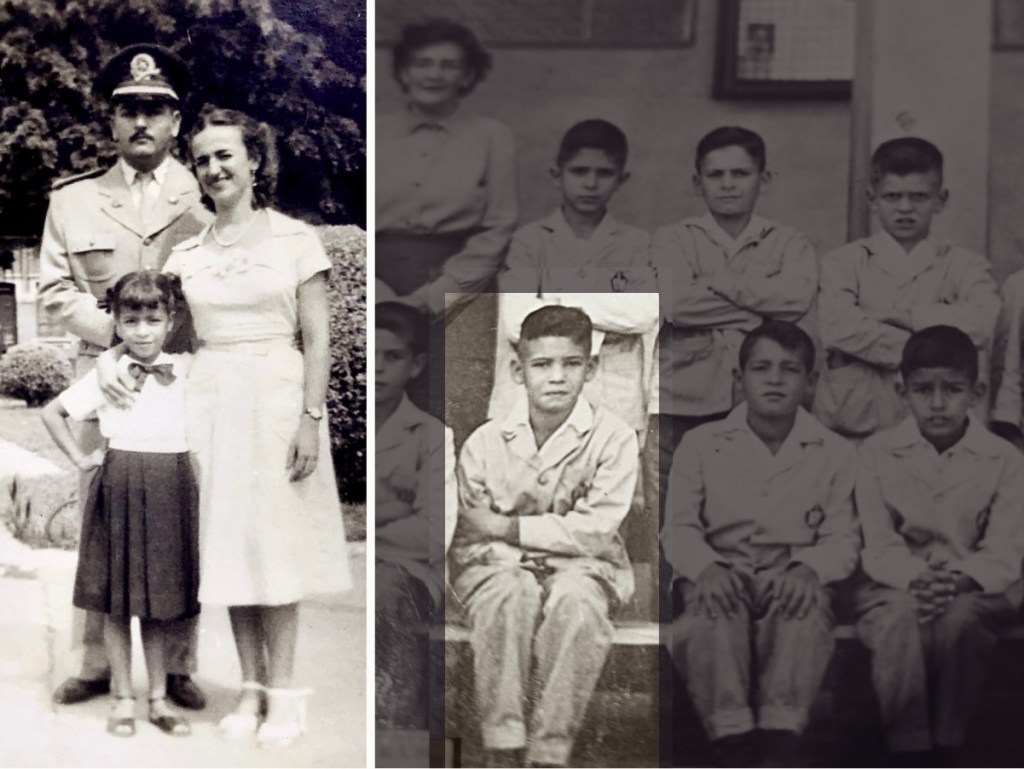

“With Mayor José de Almeida Alcântara, council members, officials, and the press in attendance, Colonel Paulo Coutinho was sworn in as Itabuna Police Chief yesterday at 3 p.m. During his speech (photo), Mayor Alcantara (pictured) emphasized the need for ‘a more effective fight against the infamous jogo do bicho [an illegal gambling numbers game, see footnotes], which is openly rampant in the city.” (Family photograph).

Colonel Paulo Coutinho

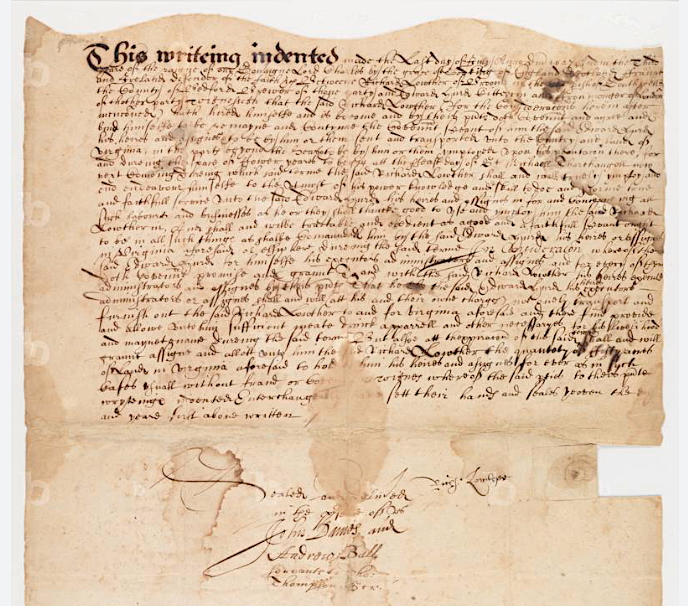

The above newspaper photograph shows Colonel Paulo Coutinho as the newly-sworn-in Itabuna Police Chief in July 1967. The excited man waving his arm is José de Almeida Alcântara, the local mayor who seems quite upset about the local goings-on of an illegal gambling numbers enterprise called Jogo de Bicho. This was a game that was extremely popular, and at the same time, extremely illegal. It preyed upon people who simply could not afford to gamble. From Wikipedia, “The game is said to have become popular because it accepted bets of any amount, in a time when most Brazilians struggled to survive a very deep economic crisis. ‘If you see two shacks lost somewhere in the backlands’ a Brazilian diplomat once observed, ‘you can bet that a bicheiro [someone connected to the game] lives in one of them and a steady bettor in the other.’”

It was Colonel Coutinho’s job to crack down on the illegal operation. This was an opportunity for someone in his position to take bribes and accept money under the table to look the other way, but he never did this. To this day, his family is quite clear that he was what could be described as a straight-arrow, who thought that living an honest life was better than advancing through corruption. (And this was during the era of a repressive military dictatorship, which his family also maintains that he steered clear of too).

“The name Military Police was only standardized in 1946 under the regime of Getúlio Vargas, with the new Constitution of 1946 after the Vargas Era of the Estado Novo (1937-1945), which had the objective of limiting the military capacity of the Public Forces in order to focus on being exclusively police forces. Historically in Brazil, ‘After World War II, the Military Police became a more traditional police force, similar to a gendarmerie, subject to the states’. Gendarmes are very rarely deployed in military situations, except in humanitarian deployments abroad. In a country like the United States, the military and police are separate in terms of they interact with the community.” Therefore, for those who are not from Brazil, this term may be misleading.

“According to Article 144 of the federal constitution, the function of the Military Police is to serve as a conspicuous police force and to preserve public order. [They] are organized as a military force and have a military-based rank structure. The commandant of a state’s Military Police is usually a Colonel. The command is divided into police regions, which deploy police battalions and companies.” (Wikipedia)

Colonel Coutinho worked in several different communities during his career: Ilhéus, Itabuna, Juazeiro, and Salvador. Some of these assignments sometimes separated him from his growing family for periods of time. (7)

Living in Ilhéus and then Piranga

The Coutinho family was a middle-class family during a time in Brazil when there were very few similar families. Indeed, from the 1950s through the 1980s, the middle class of was very small. Then things started to shift with the advancement of democracy and further economic prosperity. The “middle class comprised 15% of the Brazilian population in the early 1980s, and now they encompass nearly a third of the country’s 190 million inhabitants. It rose thanks to Brazil’s good economic performance in the recent years, poverty reduction policies, new work opportunities, and a better-educated workforce. (World Bank Group)

Circa 1969, the family moved to the northern part of Bahia for a year and lived in Piranga, at the northern border of the Bahia state. As Paulo had written in his letter to Lindaura in April 1968, “The bonus will be worth it. NBR 500.00.” This informs us that their move north was likely due to a work promotion for his career as a Colonel with the Military Police.

The Piranga community is small municipality and a suburb of Juazeiro, which “is twinned with Petrolina, in the [adjacent] state of Pernambuco. The two cities are connected by a modern bridge crossing the São Francisco River. Together they form the metropolitan region of Petrolina-Juazeiro, an urban conglomerate of close to 500,000 inhabitants’. (Wikipedia) The family returned to Ilhéus again before finally moving to Salvador in 1970. (8)

Thinking of Helena and Maria

Observation: When I was first living in Salvador da Bahia, I was startled by the sheer abundance of people who had other people available to work for them as household staff. As a middle class American child, this was not something that was even remotely available to us in any form. We always had many chores to do, in addition all the other responsibilities we bore as adolescents. — Thomas

“The end of slavery in 1888 didn’t come with any plan to integrate the black ex-slaves into a capitalist society based on paid work. While the paid jobs were offered to the Europeans that emigrated to Brazil after that time, for many of the poor and uneducated black women the only possibility was to continue working as maids”. As recalled by writer Mike Gatehouse, ‘The women… would live in a small bedroom in the working area of our flat. This was common for all my friends, as it had been for our parents. During those years chores were never part of my routine or something I had to worry about. The house worked like a hotel where rooms were cleaned, clothes washed and meals appeared as if by magic.’” (LAB — Latin American Bureau, see footnotes.)

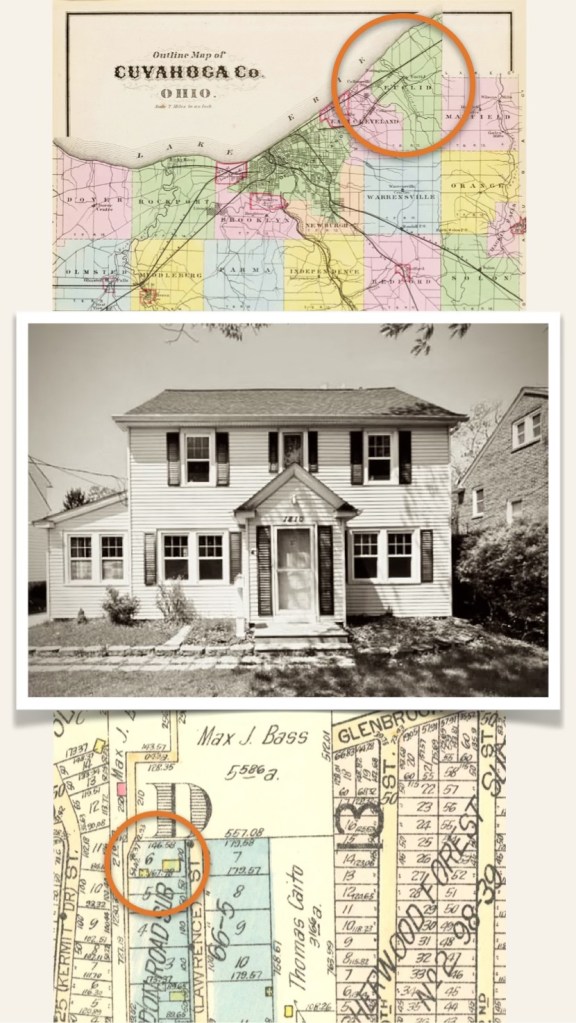

Circa 1970, Paulo was promoted again. This took the family to the coastal city of Salvador, and into the Canela neighborhood.

In Ilhéus, Piranga, and Salvador, Helena was the person who fulfilled the important role of the home-helper. She lived with the Coutinho family until she was 21 years old, and assisted with looking after the children. Furthermore, another woman named Maria worked as a domestic servant, but she did not live in the house.

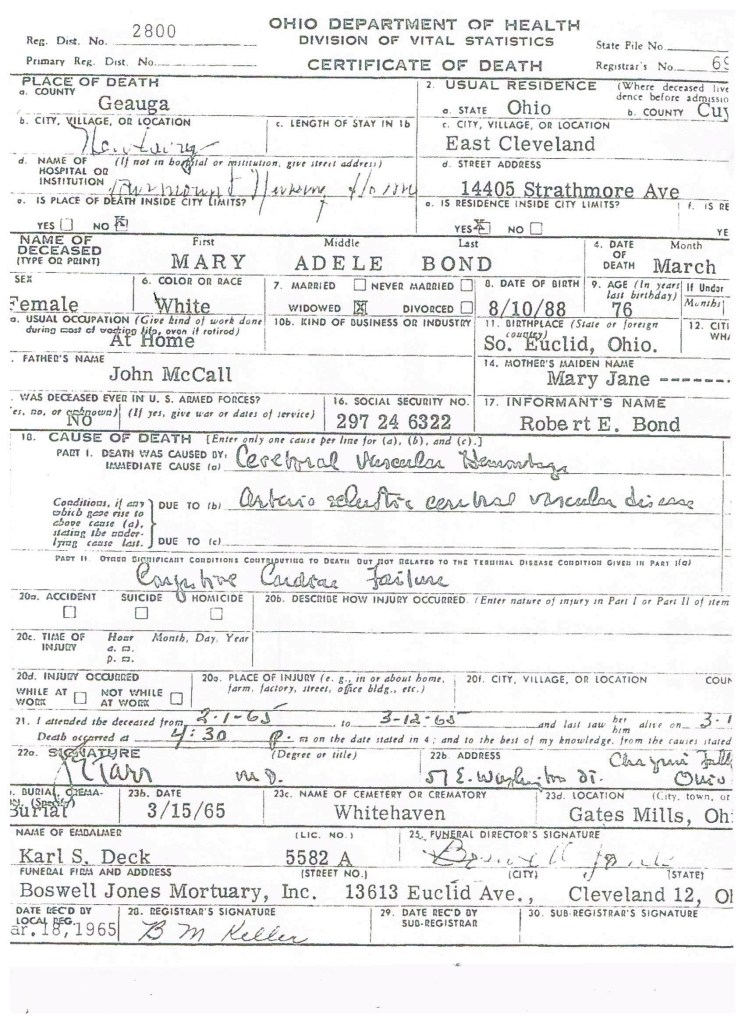

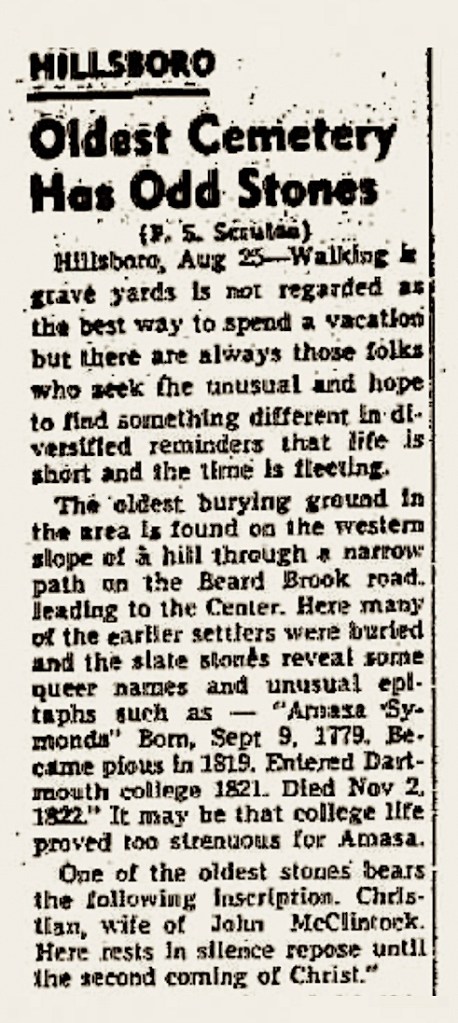

Avenida Sete de Septembre, 2155, in the Vitória neighborhood. Right: Helena, with Leandro. (Family photographs).

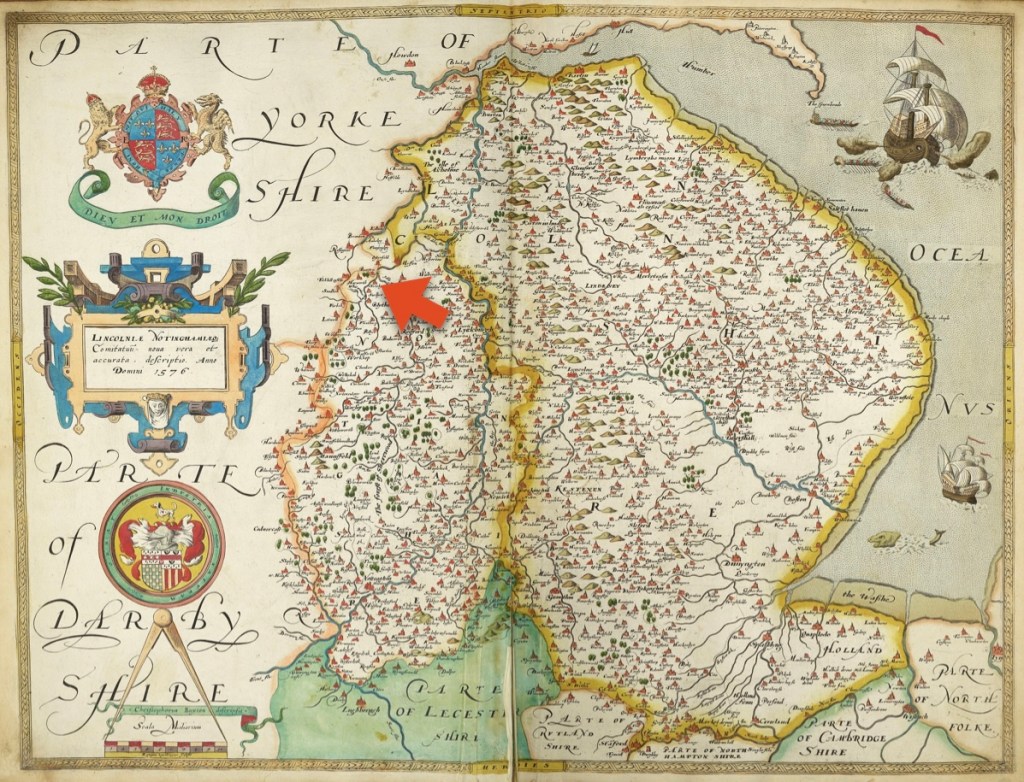

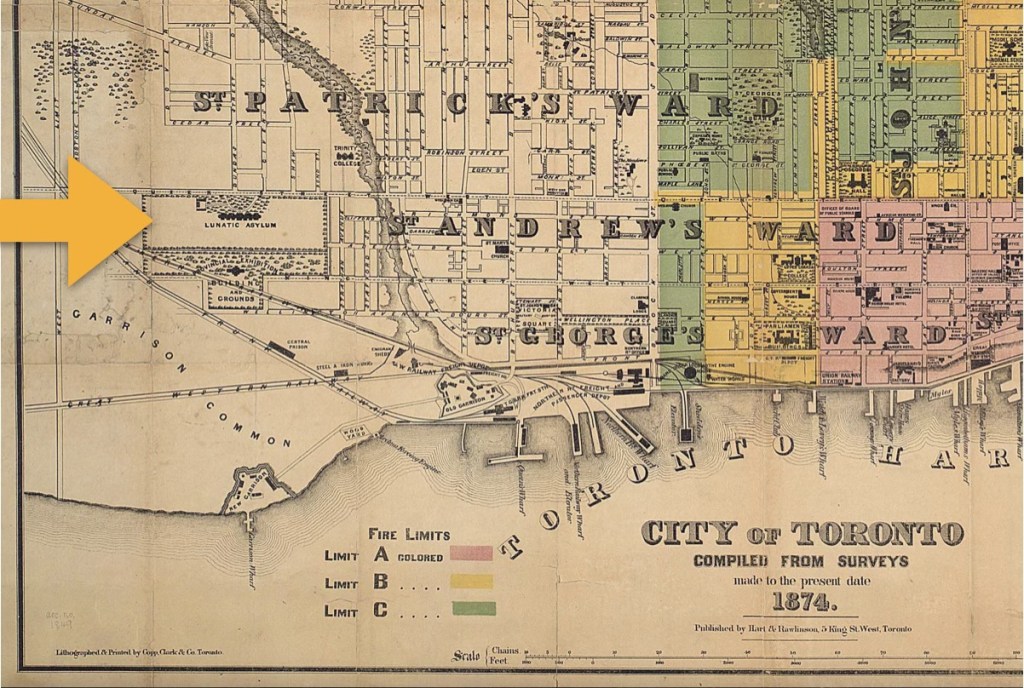

In 1975 they moved one last time, into a new home in a modern skyscraper named Edificio Júpiter, located on the celebrated Corredor da Vitória. (In Brazil, it is very common to identify buildings by their name, rather than their address). This building and the adjacent Vitória neighborhood afforded the family easy access to conveniences, good schools for the children, and quite importantly — safety, during a period of much tension in Brazil. Lindaura, the family’s mother, lived in Edificio Júpiter for 45 years.

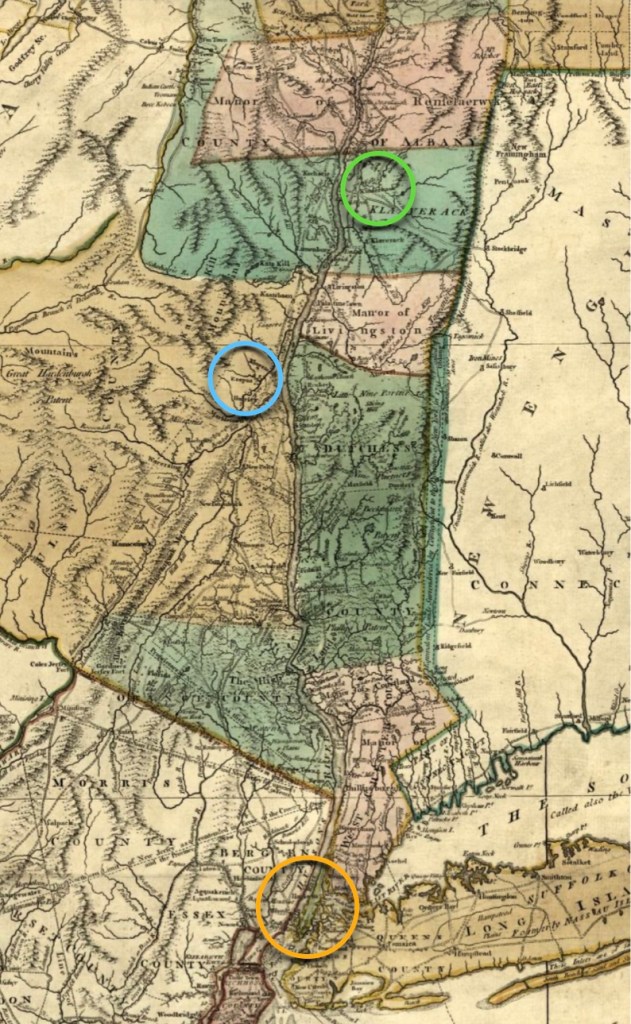

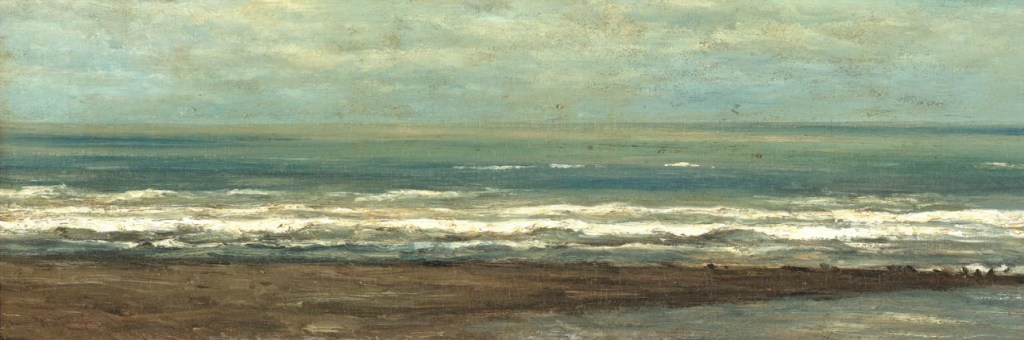

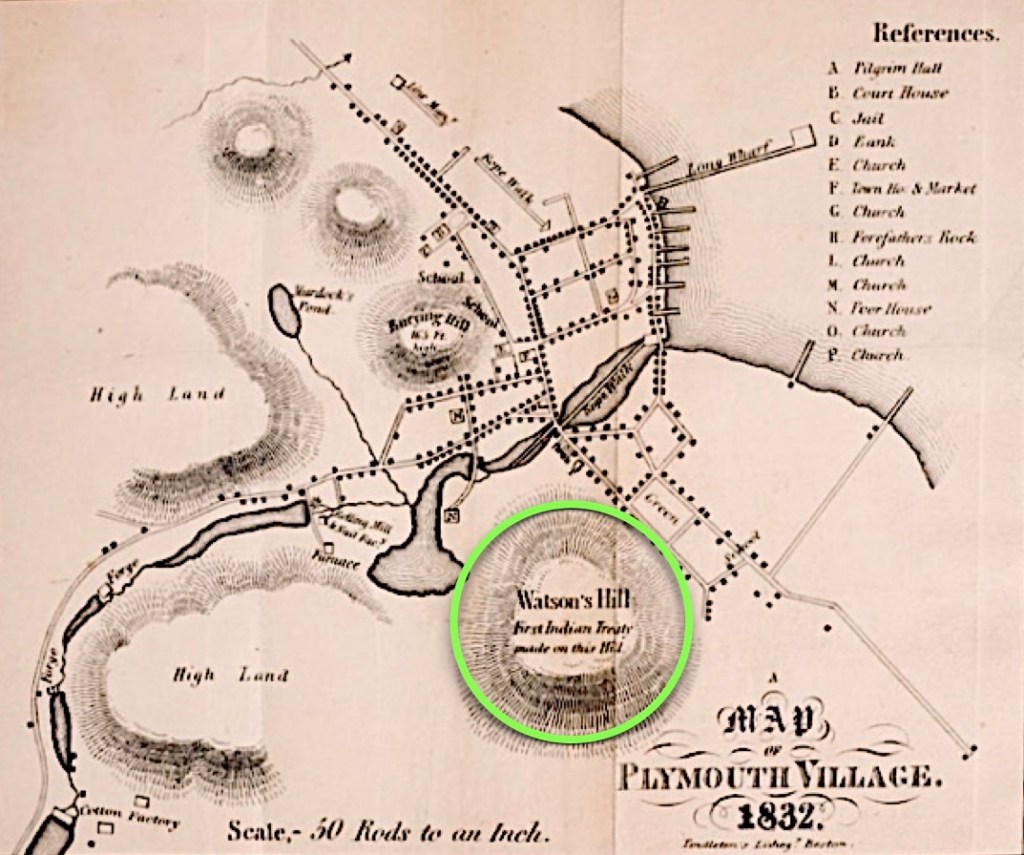

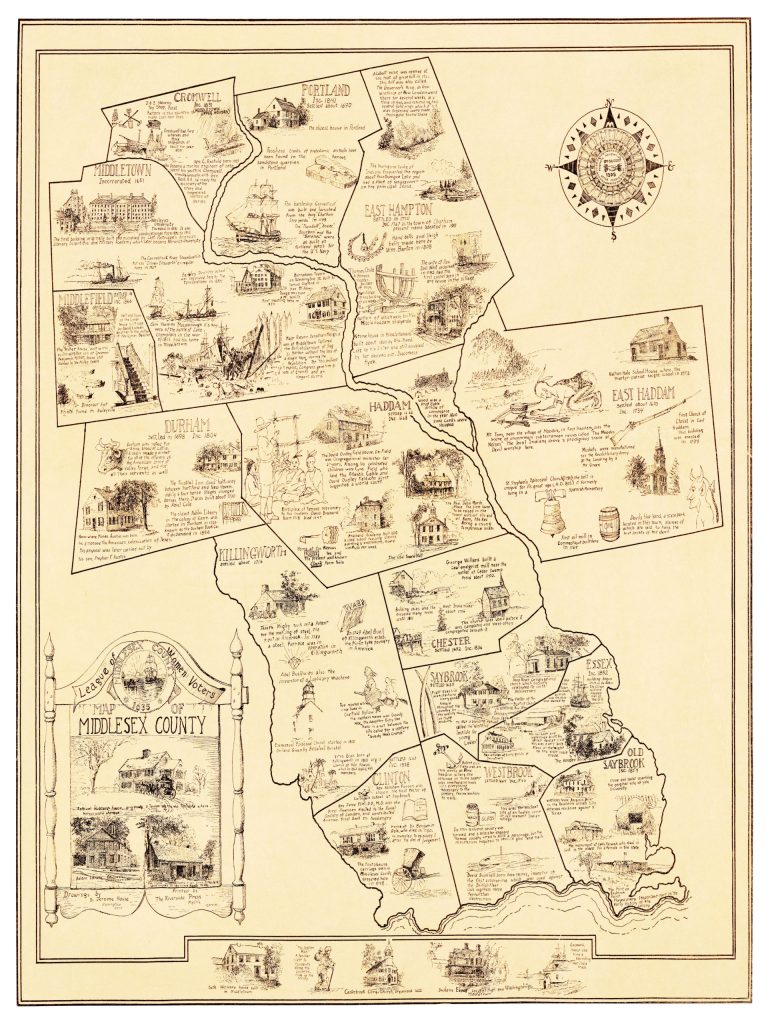

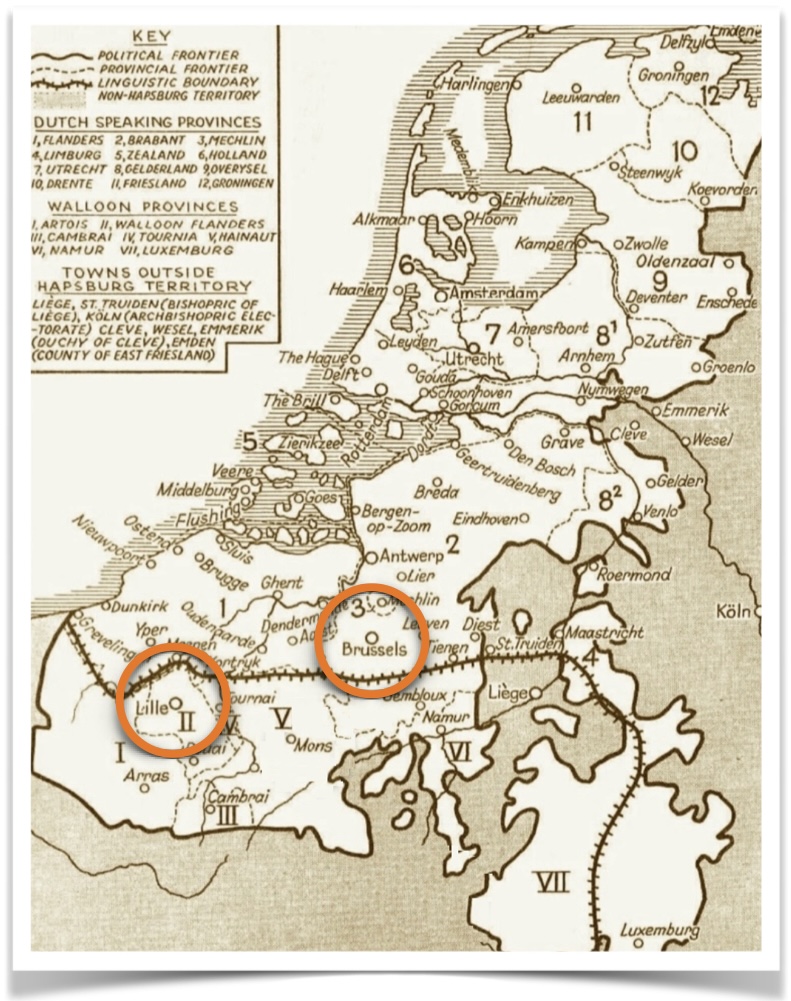

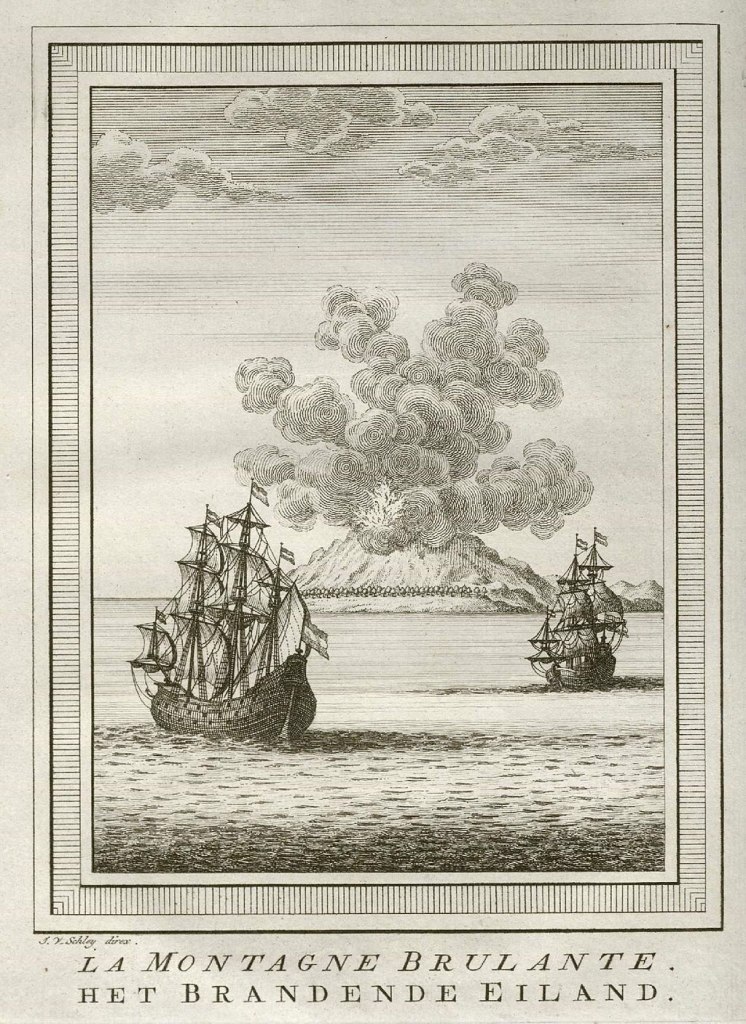

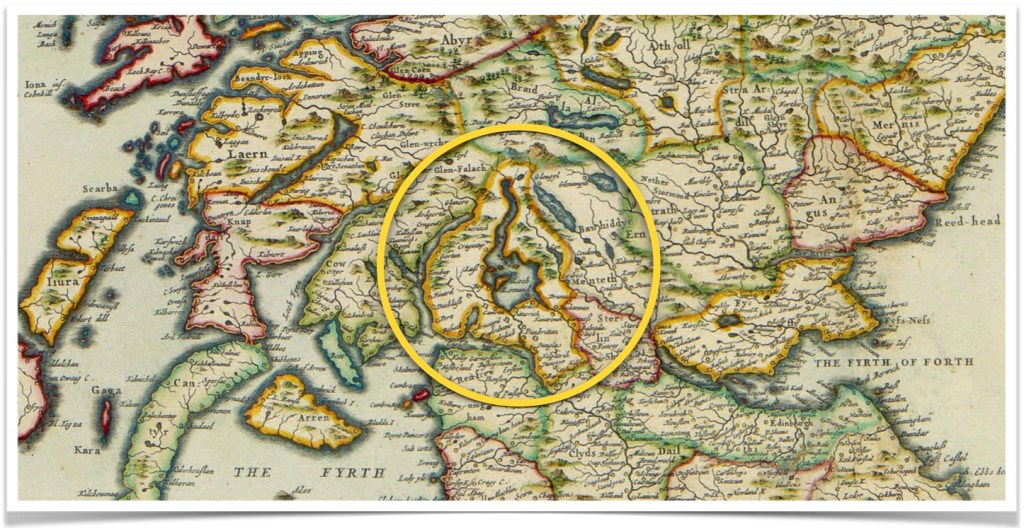

the Canela, and the Vitória districts where the Coutinho family lived.

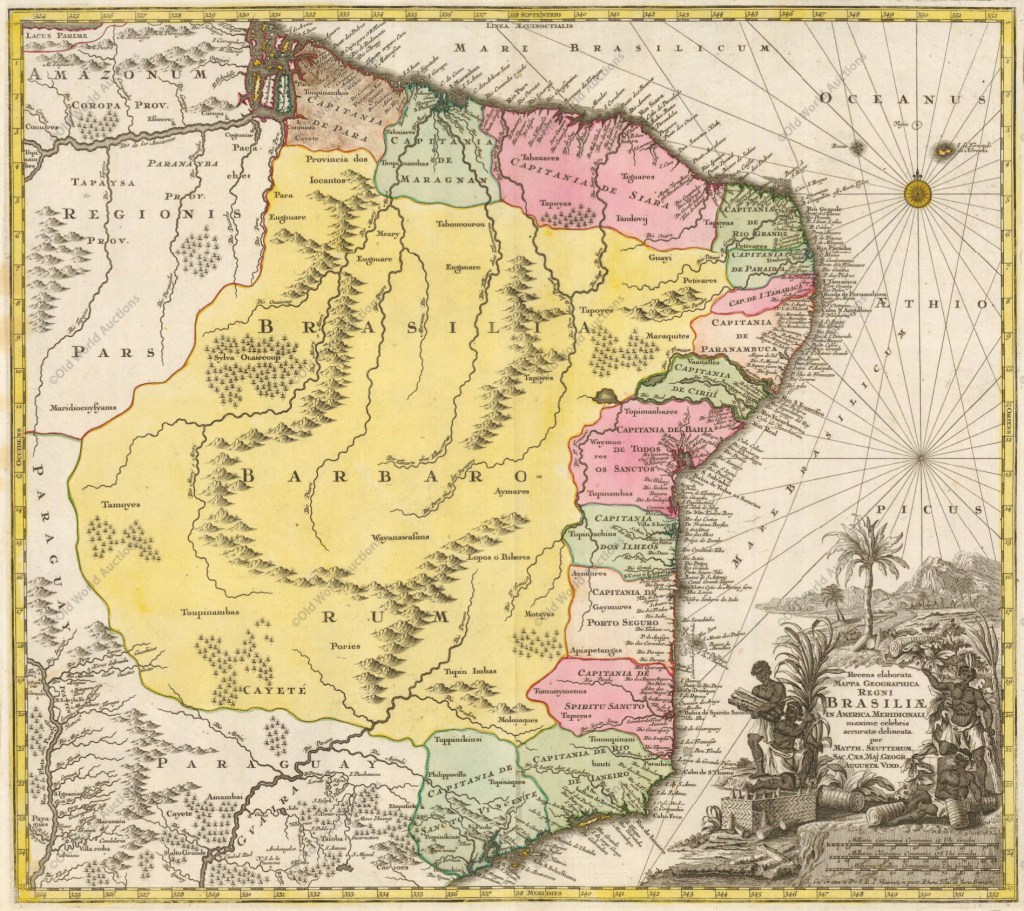

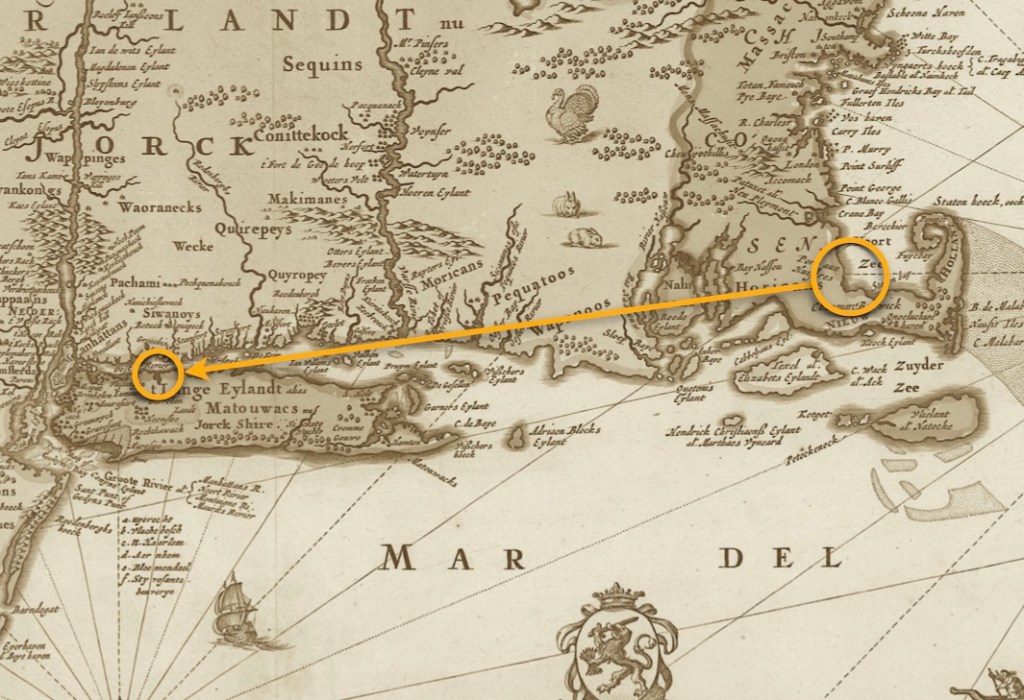

(Image courtesy of Geographicus Rare Antique Maps).

“Less than a kilometer long, the Corredor da Vitória is home to the Bahia Art Museum, the Carlos Costa Pinto Museum, and the Bahia Geological Museum. Vitória is one of the most valued urban areas in Northeast Brazil.” (Wikipedia)

Leandro remembers the many mango trees and the grand old homes which still then lined the street. Sometimes, as the older families from the previous era passed away, their homes and gardens would become abandoned, and fall into disrepair. (Most of these homes were eventually razed to make way for modern high-rise apartment buildings). To this day, he shares tales that his passion for mangos would seduce him into sneaking into these old gardens, climbing the trees, and furtively sneaking away with a clutch of fresh mangos. (9)

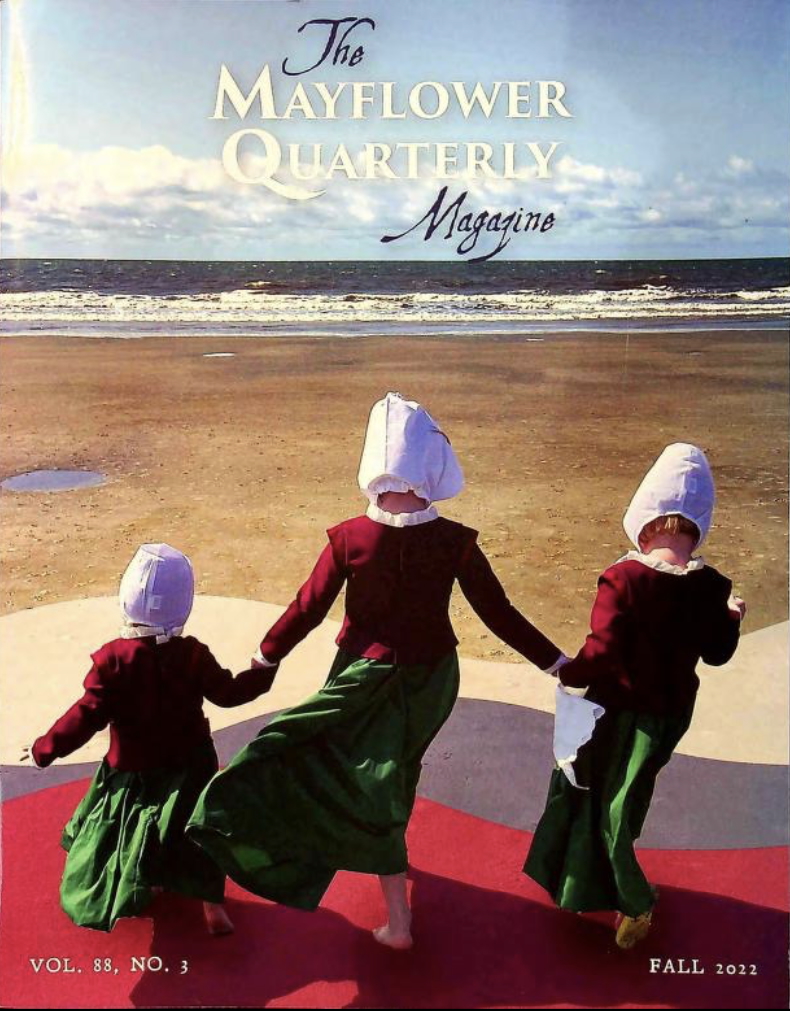

Blame It On The Bossa Nova

When Leandro and I met, it was truly North America meets South America because his English was not very good, and my Portuguese was non-existent. (He had been living for the previous decade in Germany, and France before that, so his French and German were quite good). As the North American, I was then, (and am still somewhat now), a big contrast to his skillful linguistic ability. I have always been humbled by the ease with which he fluently slips into other languages at dinner parties.

Initially at that time, I thought about what I knew about Brazil, and the answer was not too much. When I was a boy, Brazil vanished in to repressive military regime and there just wasn’t any news about it in the local newspapers. When democracy returned to Brazil between 1985 — 1988, no one I knew was paying much attention, even though we were aware of this change.

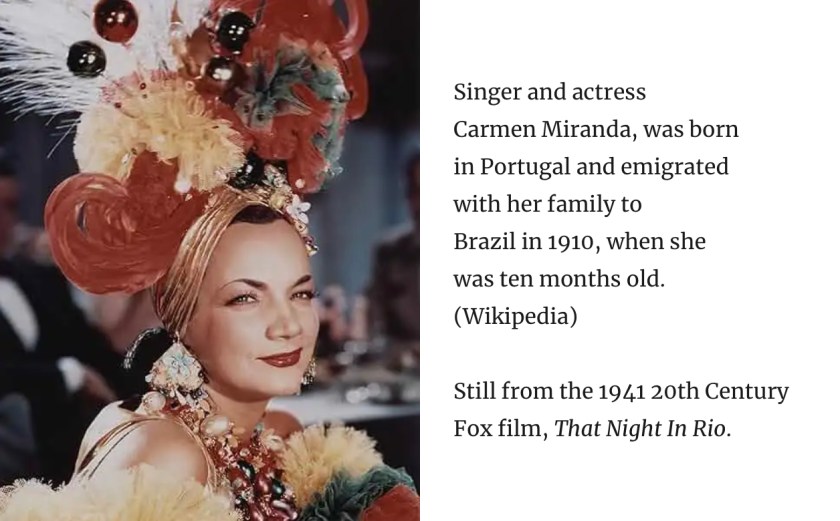

Like most Americans, if I knew much about Brazil, it was simply Carmen Miranda, and some Bossa Nova radio hits. Ms. Miranda was famous for her flair for wearing a banana hat in movies while looking lovely, (and also like she was having a lot of fun while doing this). Bossa Nova music was then translated into English for palatability to American audiences (and of course, to sell more records).

Most of us were aware of the hit song The Girl from Ipanema, which we heard on AM transistor radios. Influentialy, the band Sergio Mendes & Brazil ’66 was extremely popular in the mid-1960s, (around the time that Leandro was born). In fact, they were so famous that I still have a distinct memory of standing in a muddy field in Newbury Township, Ohio, after a rainstorm, when I was about 10 years old. I watched the Newbury High School Marching Band knock-out a pretty good version of the song Mas Que Nada (which ironically, was sung in Portuguese). I would say that it was toe-tapping good, but my boots were stuck in the mud.

For Leandro and his family lines, the Coutinhos and the Oliveiras — after many, many years, life has come full circle as we have returned to the ancient land of his ancestors. We see the world through our modern lens, thinking always about those who lived here before us. For this family line, we have reversed the tide of their past immigration, for we now live in Lisbon, Portugal. (10)

— Thomas

Following are the footnotes for the Primary Source Materials,

Notes, and Observations

A Place Quite Apart

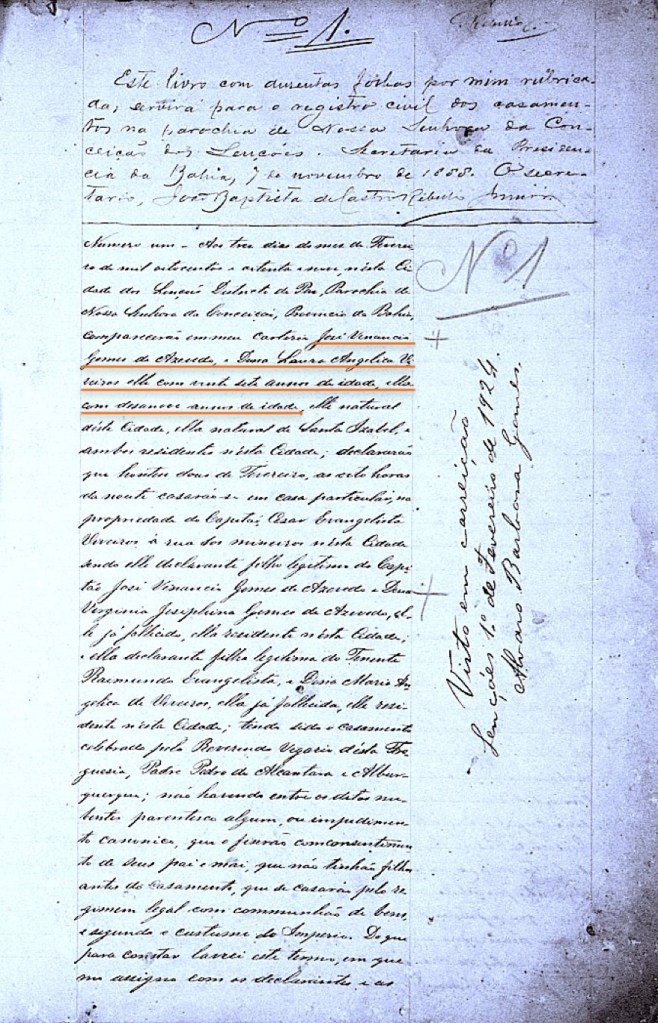

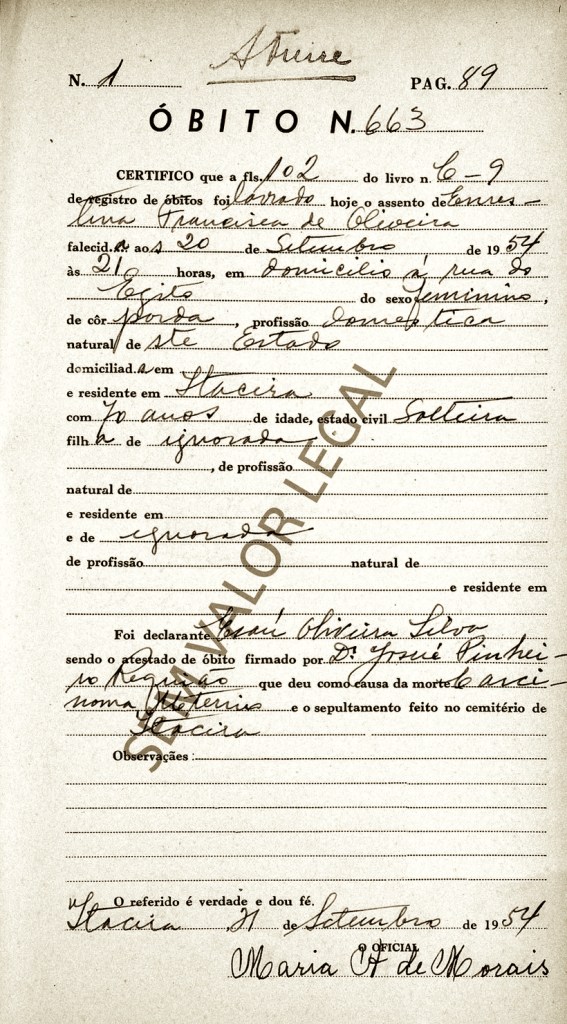

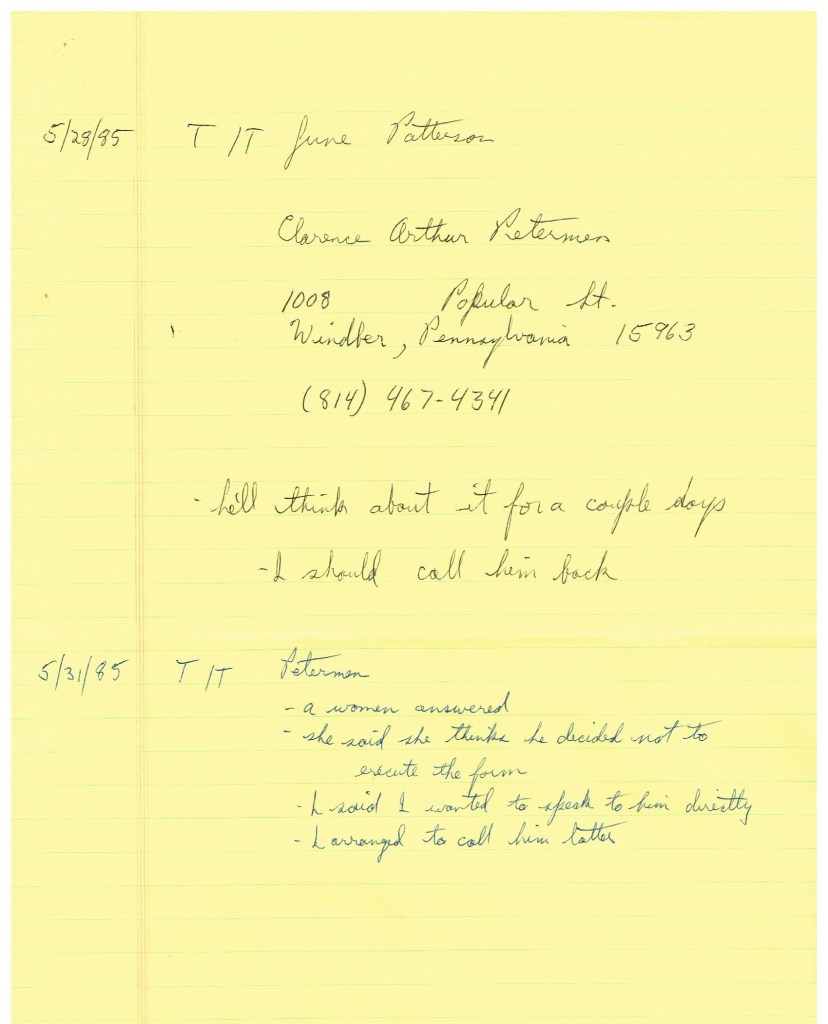

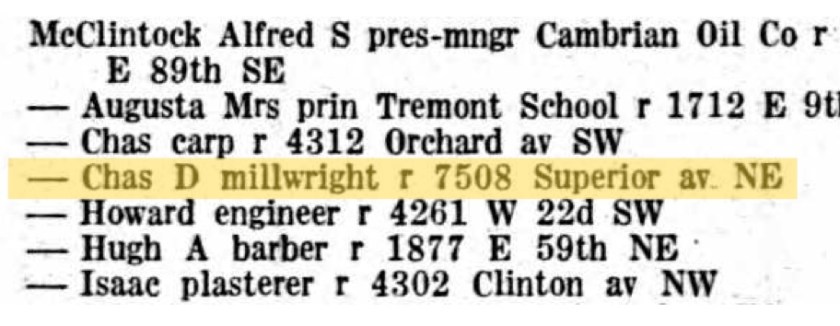

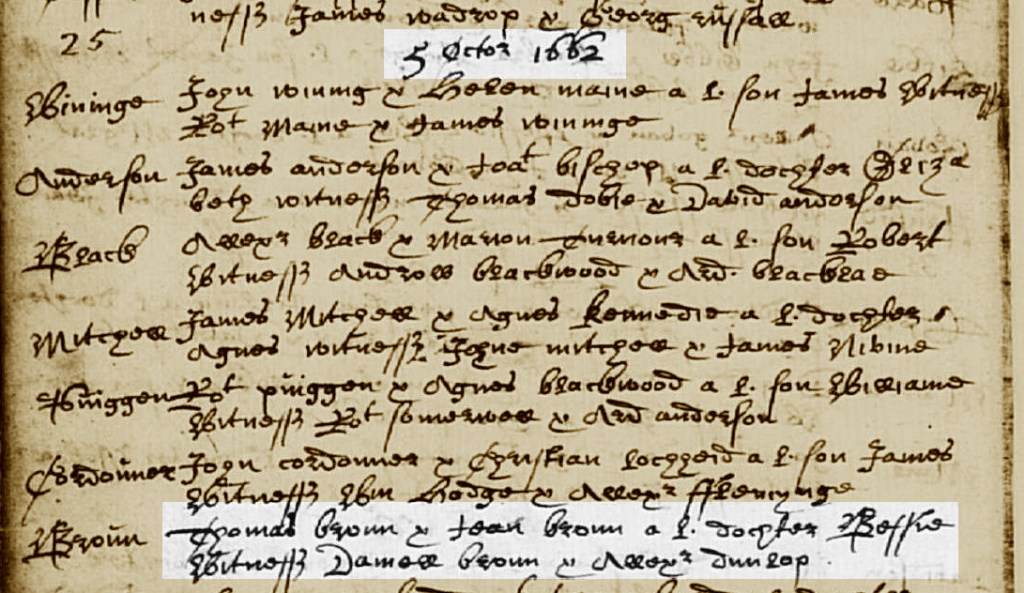

(1) — one record

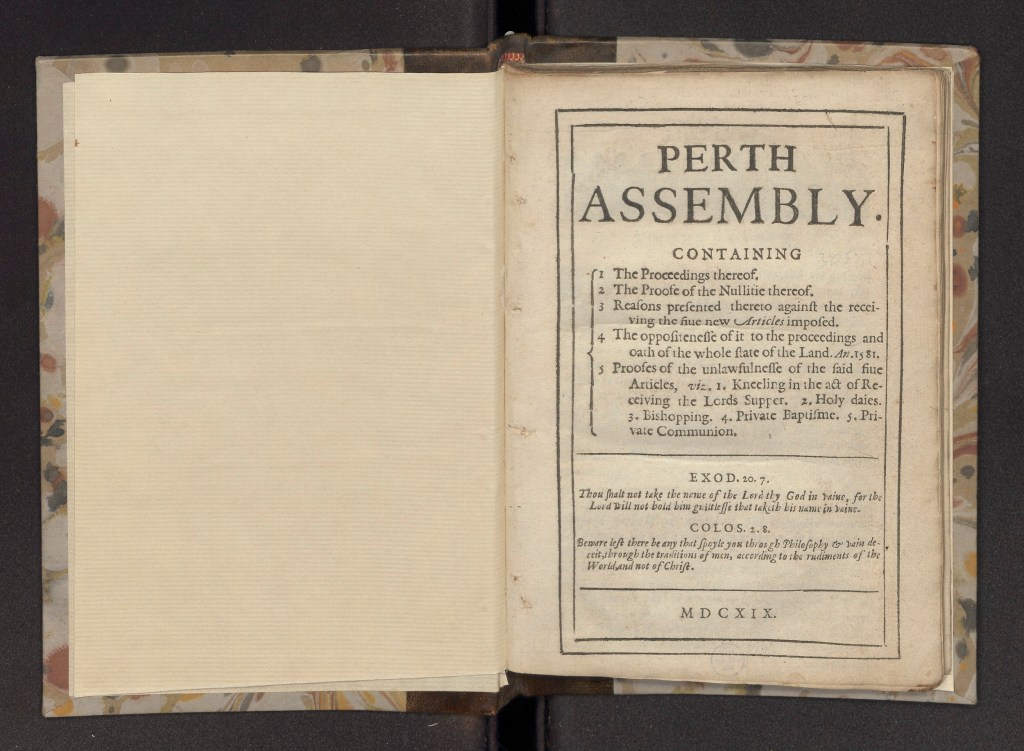

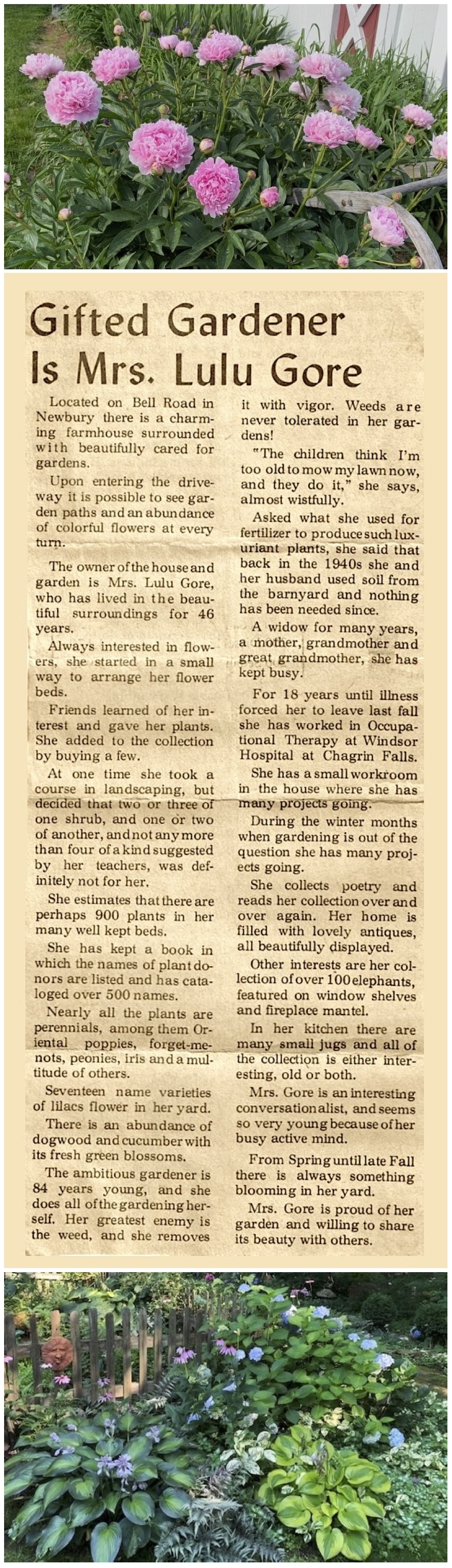

Librairie Elbé Paris

Jets to Brazil, Varig Airlines travel poster

by Artist unknown, circa 1960

https://www.elbe.paris/en/vintage-travel-posters/1618-vintage-poster-1960-jets-brazil-varig-airlines.html

Note: For the vintage poster artwork.

Catholicism is the Foundational Religion of Brazil

(2) — four records

Catholic Church in Brazil

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Catholic_Church_in_Brazil

Note: For the text.

Statues of Saints in Ouro Preto, Minas Gerais

by Photographer unknown

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Catholic_Church_in_Brazil#/media/File:-i—i-_(6288973445).jpg

Note: For the photo shown above.

Afar

The São Francisco Church and Convent

Igreja e Convento de São Francisco

https://www.afar.com/places/igreja-e-convento-de-sao-francisco-salvador

Note: For the photograph.

Church of Nosso Senhor do Bonfim, Salvador

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Church_of_Nosso_Senhor_do_Bonfim,_Salvador

Note: For the text explaining “Lembrança do Senhor do Bonfim da Bahia” (Remembrance of the Lord of Bonfim of Bahia).

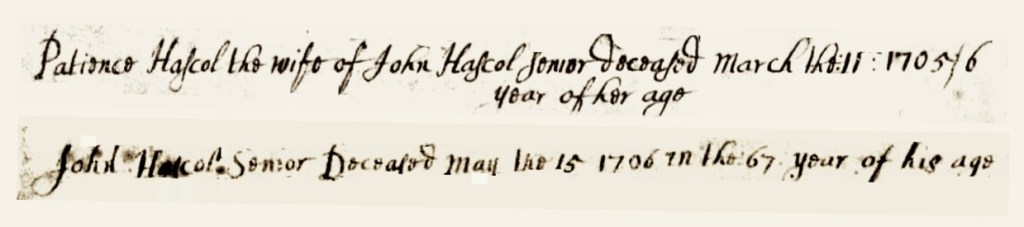

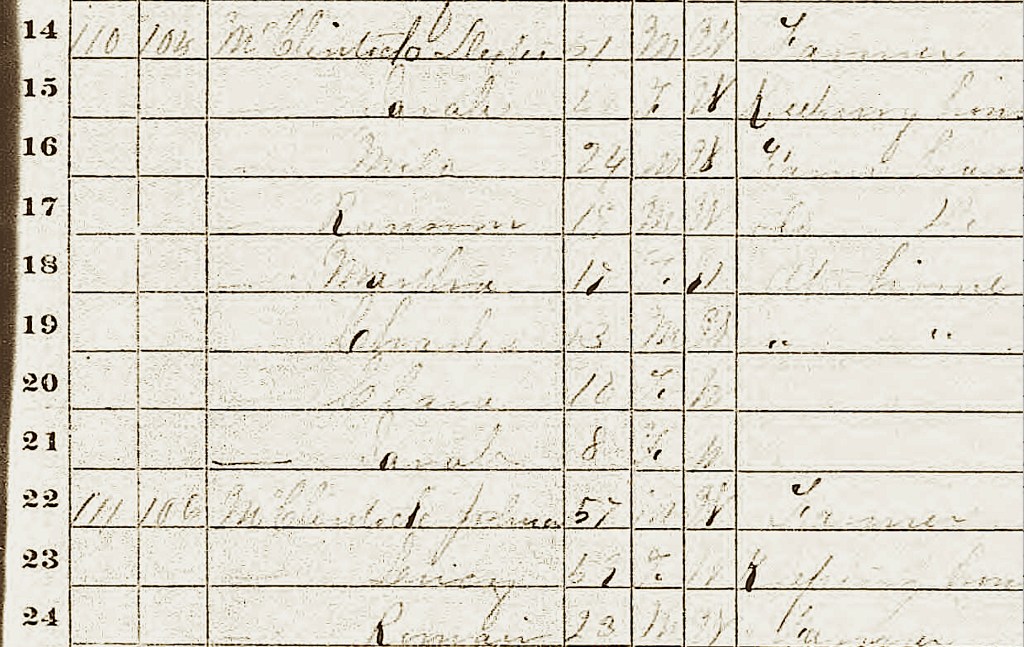

Slavery Did Not Officially End Until 1888

(3) — four records

Slavery in Brazil

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slavery_in_Brazil

Note: For the text.

Isabel, Princess Imperial of Brazil

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isabel,_Princess_Imperial_of_Brazil

Note: For the reference.

Isabel, Princess Imperial of Brazil

photographed by Joaquim Insley Pacheco, circa 1870

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isabel,_Princess_Imperial_of_Brazil#/media/File:Isabel,_Princesa_do_Brasil,_1846-1921_(cropped).jpg

Note: For her portrait.

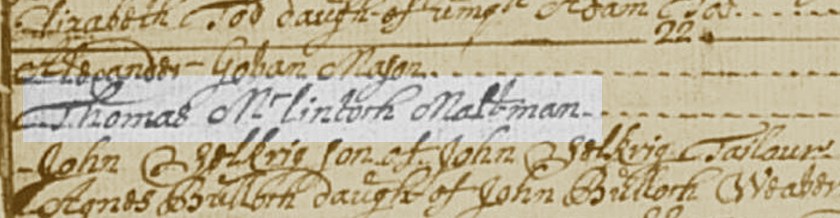

Lei Áurea

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lei_Áurea

Note: For the document image.

Candomblé and Syncretism

(4) — three records

(Image courtesy of Pinterest).

Candomblé

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Candomblé

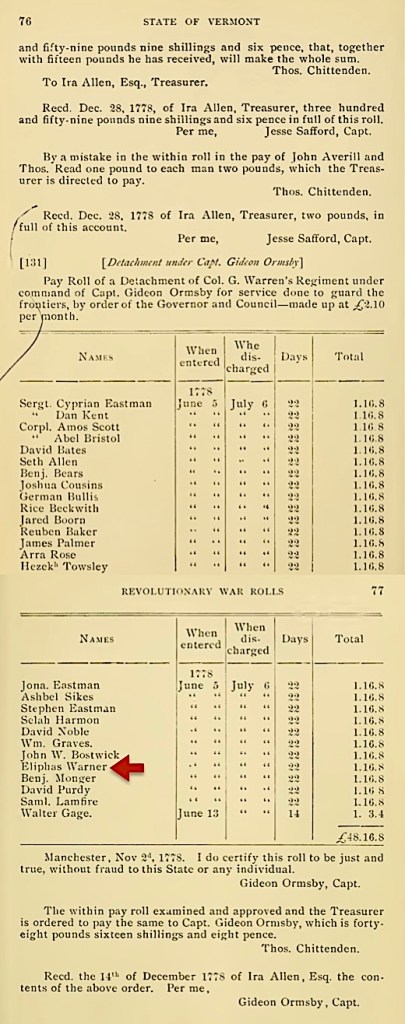

Note: For the text and historical photograph from 1902.

Altar Gods

Candomble: Afro-Brazilian Faith and the Orixas

https://altargods.com/candomble/candomble/

Note: For the text and artworks.

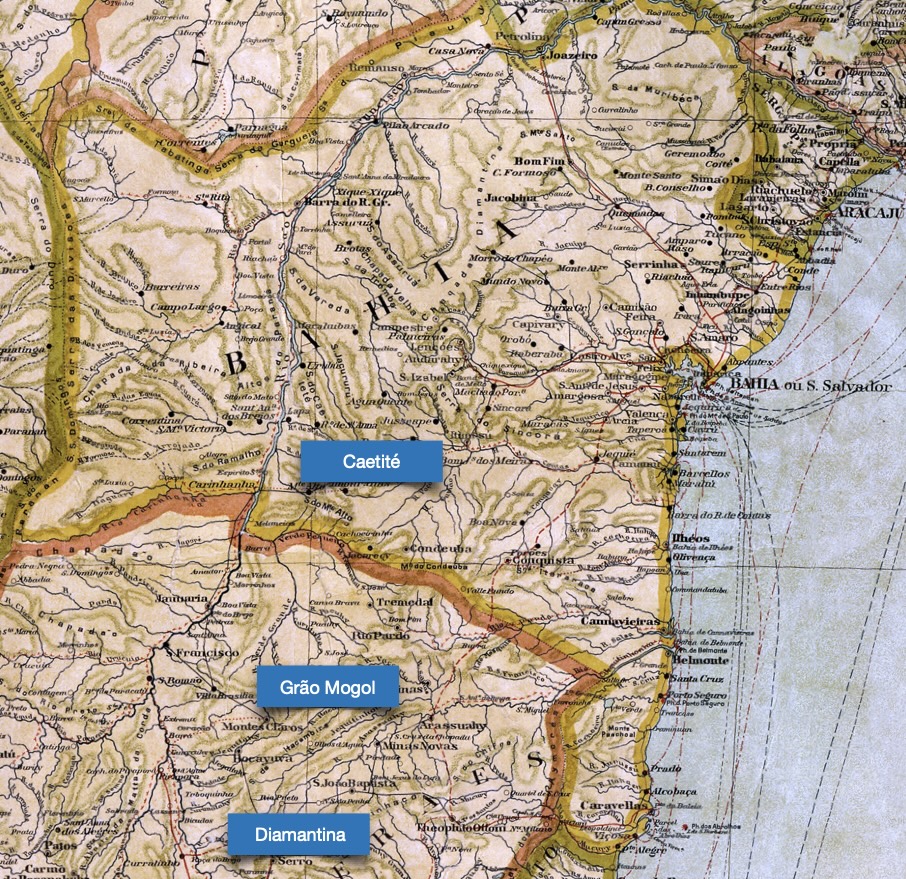

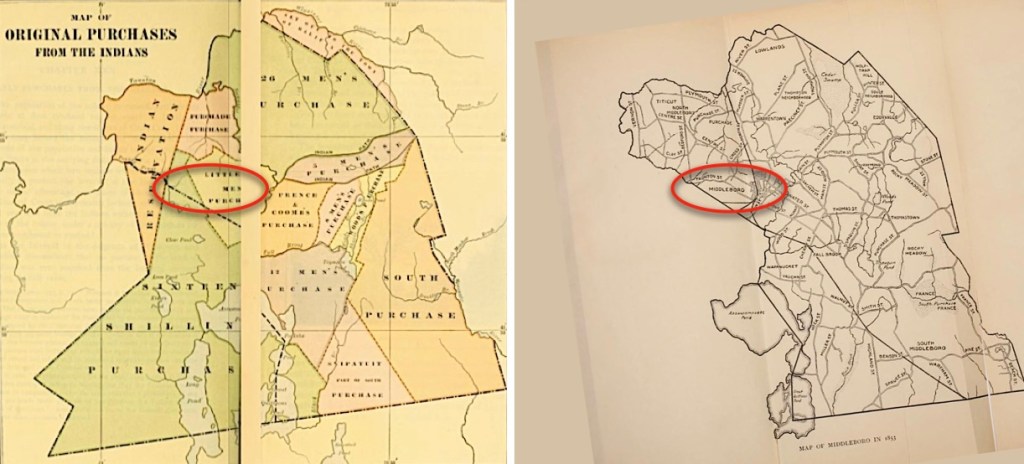

The Oliveira Family of Ubaitaba

(5) — five records

> The family photograph in this section is from the personal family photograph collection.

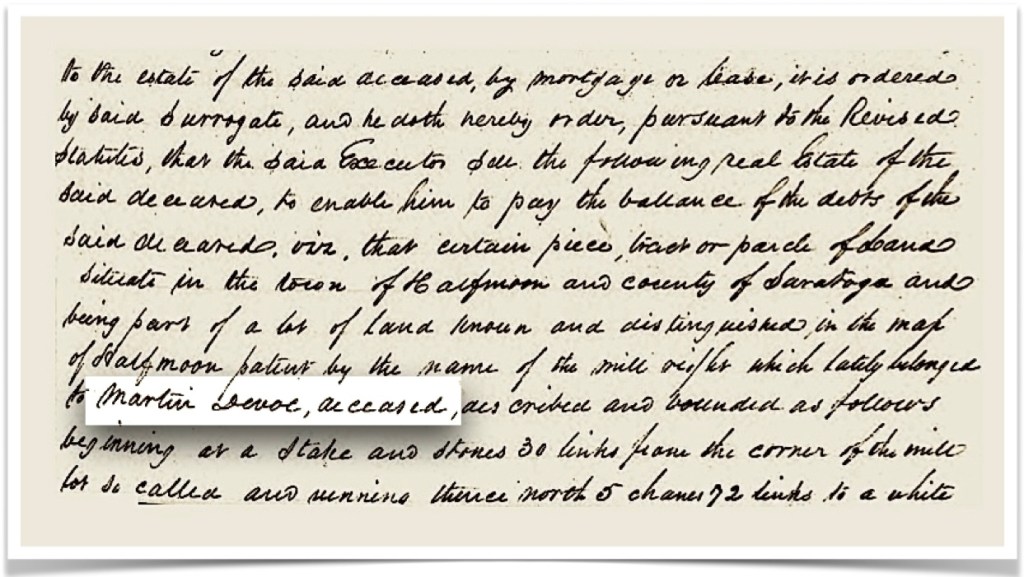

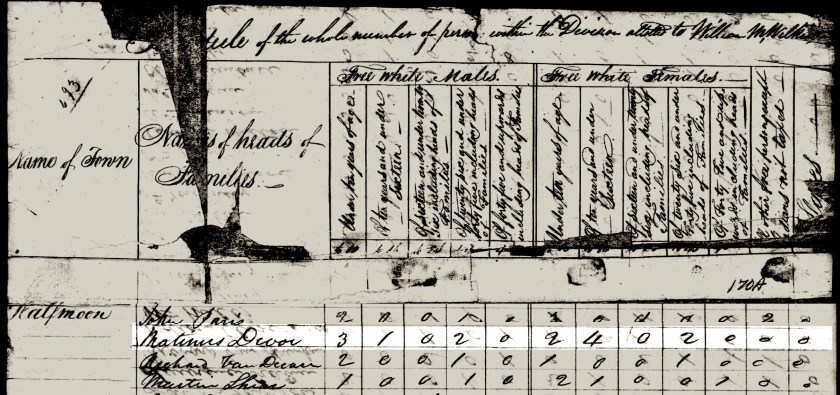

Ubaitaba

https://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ubaitaba

Note: For the text.

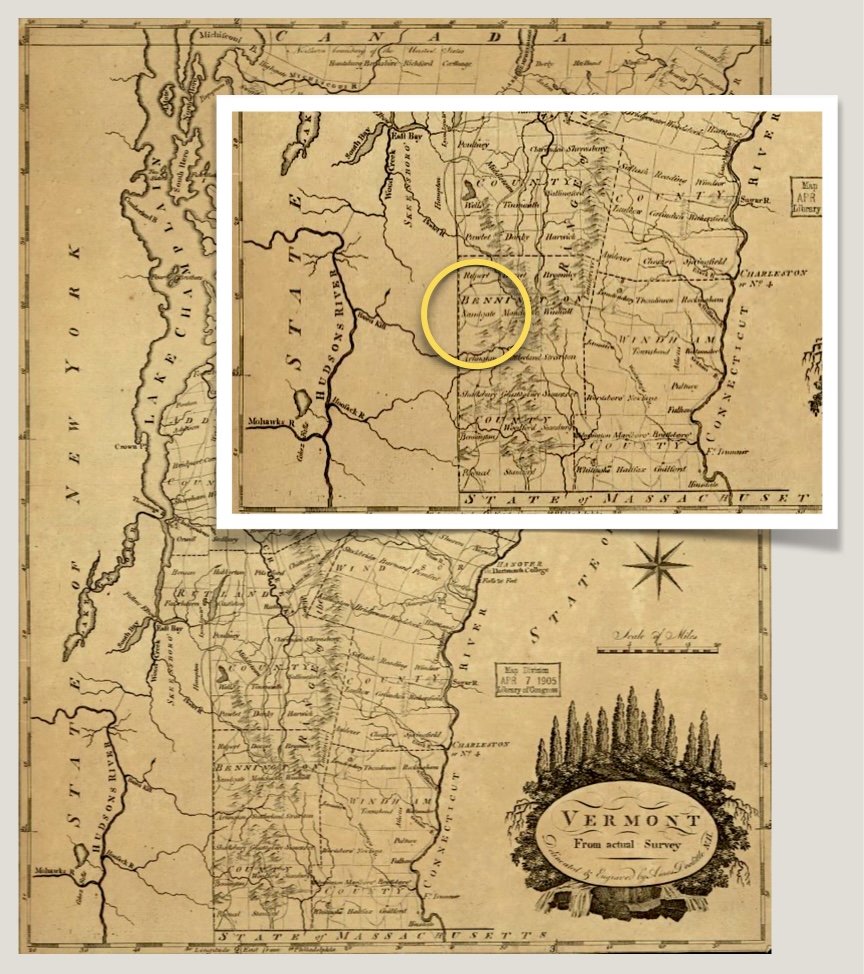

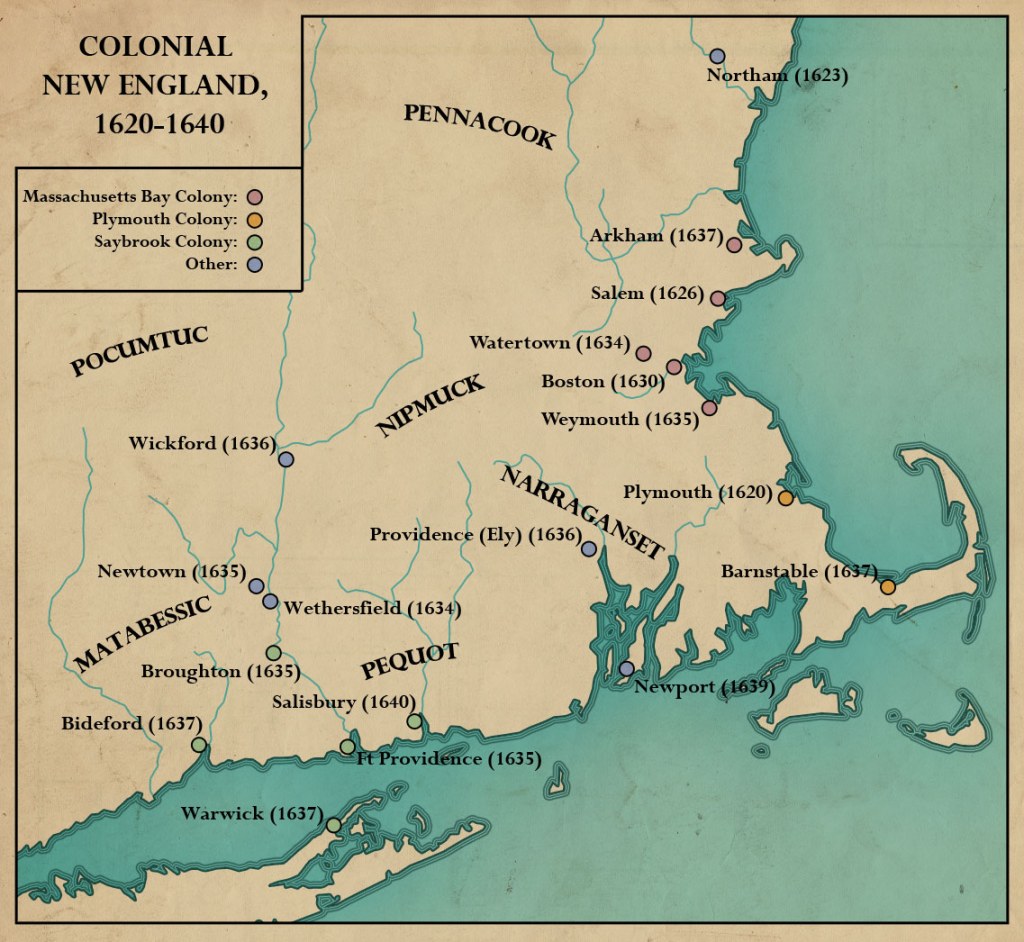

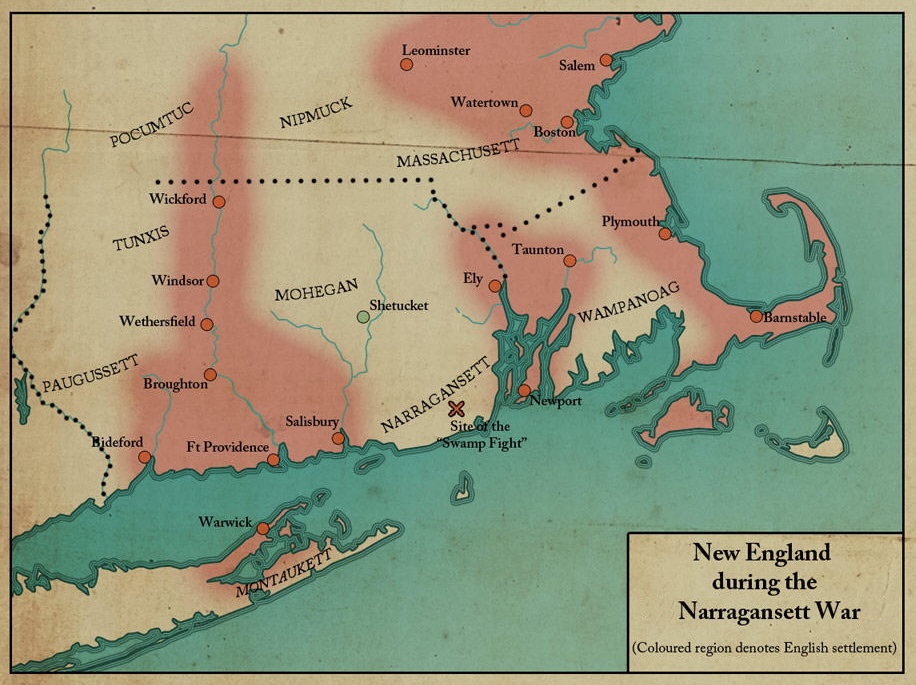

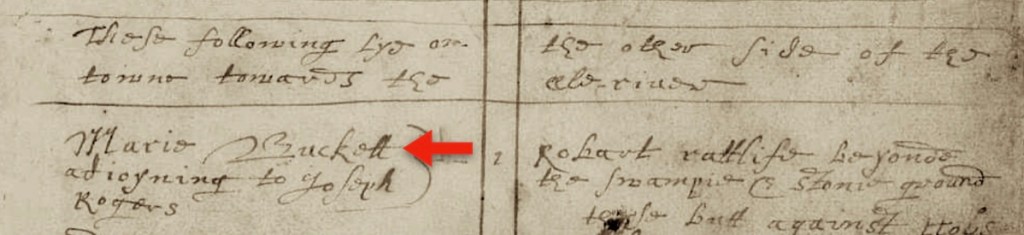

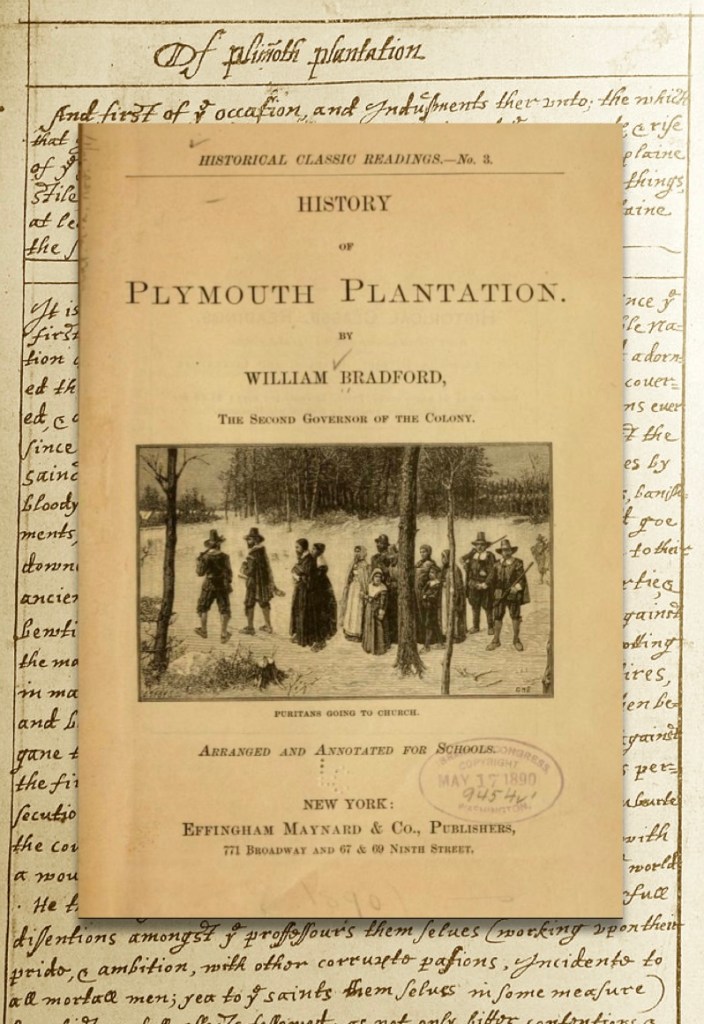

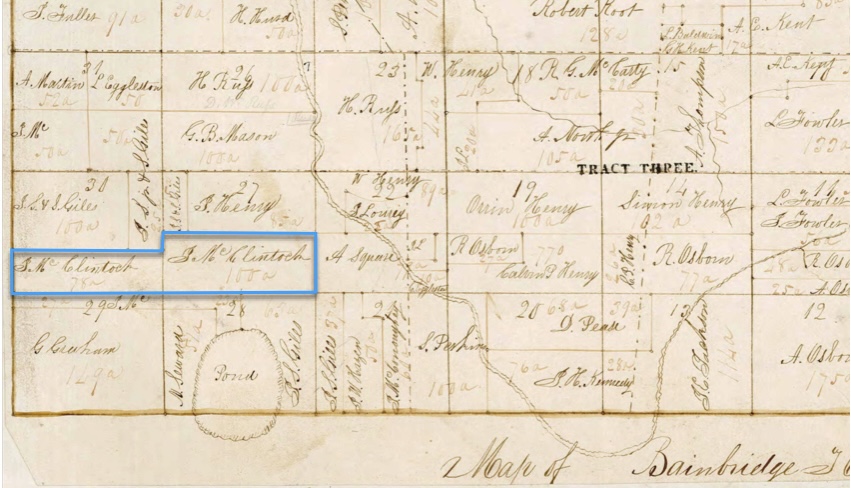

Mapas Históricos da Bahia

Mapa da Bahia de 1911

https://www.historia-brasil.com/bahia/mapas-historicos/seculo-20.htm

Notes: This is a excerpted portion of the General Map of Brazil published in January 1911, and organized by the company Hartmann-Reichenbach. The red lines are railways.

Ubaitaba.com

História Regional and História

http://ubaitaba.com/historia-regional/

Note: Upper photographs are from the website section labeled História Regional and História.

Restos de Colecção

Mercearias e Mini-Mercados

https://restosdecoleccao.blogspot.com/2013/05/mercearias-e-mini-mercados.html

Note: For the lower photograph titled Antigas Mercearias.

“You can’t imagine how much I’ve missed you…”

(6) — nine records

> The family photographs in this section are from the personal family photograph collection.

Jorge Amado, August 10, 1912 — August 6, 2001) “…was a Brazilian writer of the modernist school. He remains the best-known of modern Brazilian writers, with his work having been translated into some 49 languages and popularized in film, including Dona Flor and Her Two Husbands in 1976, and having been nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature at least seven times.

His work reflects the image of a Mestiço* Brazil and is marked by religious syncretism. He depicted a cheerful and optimistic country that was beset, at the same time, with deep social and economic differences.” (Wikipedia) *Mestiço is a Portuguese term that refers to persons of mixed race, as people from European and Indigenous non-European ancestry.

Jorge Amado

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jorge_Amado

Note: For the text.

Fundação Casa de Jorge Amado

https://www.jorgeamado.org.br/

Note: For his portrait.

Brazilian Publishers

3 Books to Get to Know The Work of Jorge Amado,

Master of Social Realism and Bahian Imagination

https://brazilianpublishers.com.br/en/noticias-en/3-books-to-get-to-know-the-work-of-jorge-amado-master-of-social-realism-and-bahian-imagination/

Note: For the text.

The Brazilian Publishers website recommends that these “three essential books [which should be read] to discover the strength and diversity of his literature”. (The descriptive text below is from their website).

- Captains of the Sands (Capitães da Areia)

In the book, we follow Pedro Bala, Professor, Gato, Sem Pernas and Boa Vida, marginalized young people who grow up on the streets of Salvador. Living together at Trapiche, they form a close-knit community. The arrival of Dora and her brother Zé Fuinha, brought by Professor, causes a stir among the boys, who are not used to the female presence. Slowly, an emotional bond develops between the group’s leader and the girl.

Captains of the Sands

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Captains_of_the_Sands

Note: For the reference. - Dona Flor and Her Two Husbands (Dona Flor e Seus Dois Maridos)

The story begins during the 1943 carnival in Bahia, when Vadinho, a womanizer and inveterate gambler, suddenly dies. Dona Flor, his wife, is inconsolable. Some time later, she marries Teodoro Madureira, a pharmacist who is the opposite of her first husband. Together, they have a stable and peaceful, but boring, life until the day when Vadinho’s ghost appears in Dona Flor’s bed.

Dona Flor and Her Two Husbands (novel)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dona_Flor_and_Her_Two_Husbands_(novel)Note: For the reference. - Gabriela, Clove and Cinnamon (Gabriela, Cravo e Canela)

The book tells the story of the romance between Nacib and Gabriela, set in Ilhéus in the 1920s, during the city’s cocoa-driven development. Gabriela’s sensuality wins over Nacib and many men, defying the law against female adultery. Published in 1958, the book was a worldwide success and became an acclaimed Brazilian soap opera.

Gabriela, Clove and Cinnamon

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gabriela,_Clove_and_Cinnamon

Note: For the reference.

Mestiço

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mestiço

Note: For the data.

Colonel Paulo Coutinho

(7) — four records

> The family photograph in this section is from the personal family photograph collection.

Jogo do bicho

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jogo_do_bicho

Note: For the reference.

Military Police (Brazil)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Military_Police_(Brazil)#:~:text=The Military Police was founded,on being exclusively police forces.

Note: For the text.

Gendarmerie

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gendarmerie

Note: For the reference.

World Bank Group

In Brazil, an emergent middle class takes off

https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2012/11/13/middle-class-in-Brazil-Latin-America-report

Note: For the text.

Living in Ilhéus and then Piranga

(8) — three records

> The family photographs in this section are from the personal family photograph collection.

Exposição “Carybé e o Povo da Bahia”

celebra a identidade cultural no Museu de Arte da Bahia

https://jornalgrandebahia.com.br/2024/12/exposicao-carybe-e-o-povo-da-bahia-celebra-a-identidade-cultural-no-museu-de-arte-da-bahia/

Note: For the Carybé illustrations above.

Juazeiro

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juazeiro

Note: For the text.

Thinking of Helena and Maria

(9) — four records

> The family photograph in this section is from the personal family photograph collection.

LAB – Latin American Bureau

Brazilian Maids: A Photo Essay

by Mike Gatehouse

https://lab.org.uk/brazilian-maids-a-photo-essay/

Note: For the text.

Vitória (Salvador)

https://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vitória_(Salvador)

Note: For the text.

Geographicus Rare Antique Maps

1931 Papelaria Brazileira City Plan of Salvador, Brazil

https://www.geographicus.com/P/AntiqueMap/salvadorbahia-papelariabrazileira-1931

Note: For the map image.

Blame It On The Bossa Nova

(10) — two records

Sérgio Mendes

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sérgio_Mendes

Note: For the reference.

and

Herb Alpert Presents Sergio Mendes & Brasil ’66

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herb_Alpert_Presents_Sergio_Mendes_%26_Brasil_%2766

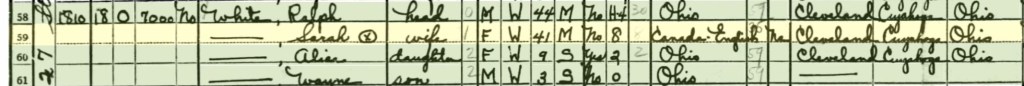

Note: For the album cover artwork.