This is Chapter Two of seven, where we explain just what the heck was going on in Scotland and England with all of the squabbling going on between the various monarchs. We also get to meet our 6x Great-Grandfather and his family, who were definitely not monarchs!

If you are a stickler for details as we are…

… then we really like you! Sometimes we need to pause and explain why we see records which have odd differences when they are recording similar information. A note about place names, standard spelling, and what is this shire thing all about?

Shire means that the area is the fiefdom of a Sheriff. Not the type of Sheriff you and I might encounter today, but one from the Middle Ages. It all begins with “Malcolm III (reigned 1058 to 1093) appears to have introduced sheriffs as part of a policy of replacing previous forms of government with French feudal structures. This policy was continued by Edgar (reigned 1097 to 1107), Alexander I (reigned 1107 to 1124)…” and so on and so forth, and finally, “were completed only in the reign of King Charles I (reigned 1625 to 1649)”.

“Historically, the spelling of the county town and the county were not standardized. By the 18th century the names County of Dunbarton [with n]and County of Dumbarton [with m] were used interchangeably”. Additionally, “In Scotland, as in England and Wales, the terms ‘shire’ and ‘county’ have been used interchangeably, with the latter becoming more common in later usage. Today, ‘county’ is more commonly used, with ‘shire’ being seen as a more poetic or [an] archaic variant”. (Wikipedia)

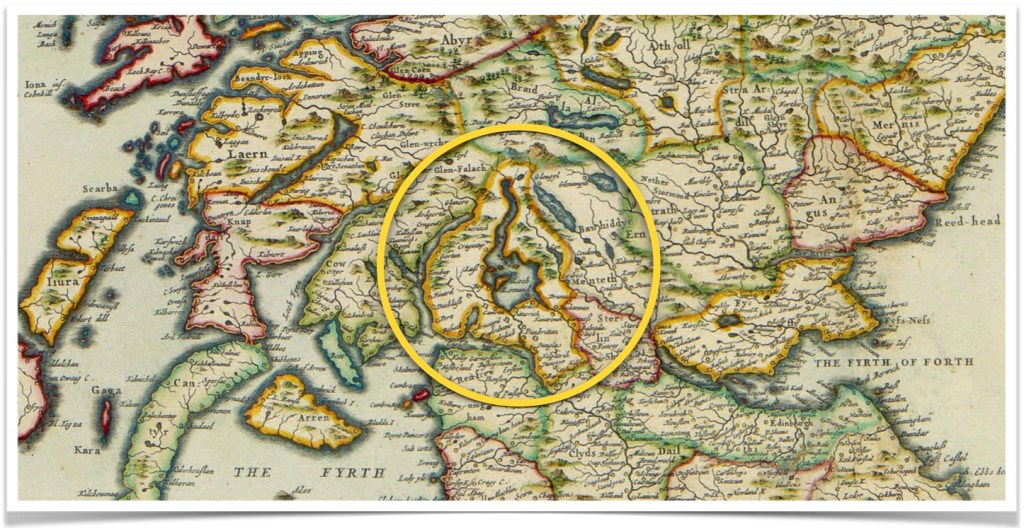

In practical terms, this means that the area near Loch Lomond is called: Dunbarton > Dunbartonshire > County of Dunbarton (with either n or m). Similarly, the area south of there around Glasgow is called: Lanark > Lanarkshire > County of Lanark. (1)

The Central Belt of Scotland

If you look at this map from 1710, you can observe a cinched-in area in central Scotland that looks like the country is almost corseted, (see the yellow oval). The McClintocks and the other families from the surrounding communities, lived in this area — what is generally still referred to as the Central Belt of Scotland. These generations from the 1600s were the parents and grandparents of our ancestors.

Observation: Sometimes ancestry research is like a treasure hunt through the internet with many red herrings thrown into your path. This is the case with this family, which we originally thought was from Bonhill, Dunbartonshire, but when we looked much more closely at the details — we saw lots of things that made us reconsider the paths other researchers had taken. Suffice it to say that we found accurate, reliable records for our family. (2)

The Thomas Mclintoch Family of Glasgow

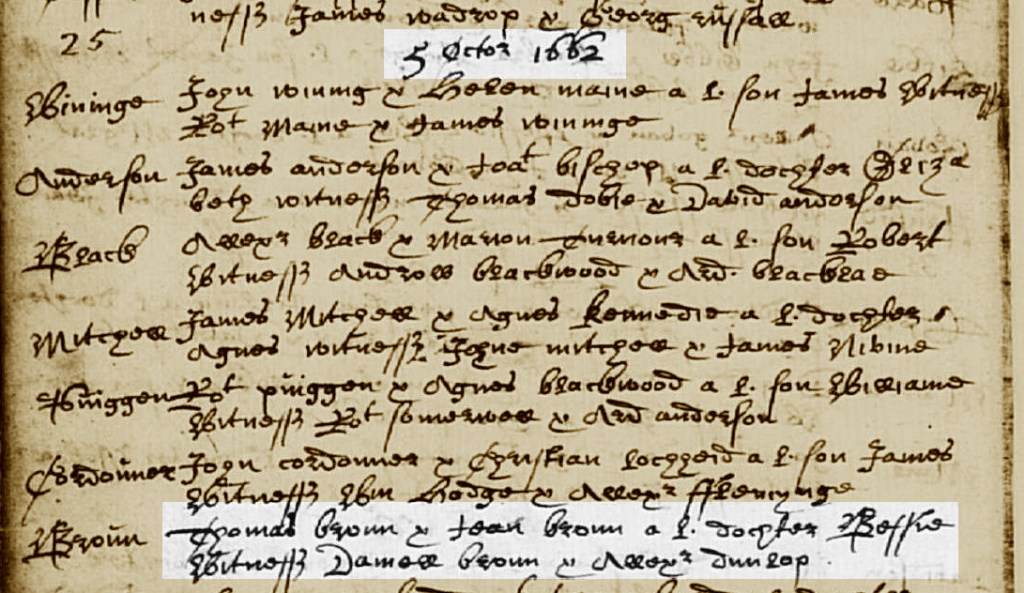

Our 7x Great Grandparents are Michael Mclintoch and Jonat Wining. [Note the spelling of McClintock for this family.] They had a son named Thomas Mclintoch who married Margarit Gilhagie, our 6x Great Grandparents. We don’t know Thomas’s birthdate, but we know he was baptized on October 5, 1662 by his parents at the High Church of Glasgow, Lanark, Scotland. This building in the present day, “is the oldest cathedral in mainland Scotland and the oldest building in Glasgow.” (Wikipedia) The name High Church is how it was referred to after 1560.

Honestly, we’re not sure if this is written in Latin (?) or perhaps, in Scottish Gaelic?

Thomas and his wife Margarit (Gilhagie) Mclintoch on March 10, 1698 baptized their son, Michael Mclintoch, who was likely named for his grandfather. He must have died young because they used the name Michael again for another son born later. (Comment: This idea of repeating a deceased child’s name for a later subsequent child might seem very odd to us today. However, we have seen this in many family lines during earlier centuries.)

On September 18, 1709, they had twin boys and named them Michael and William. (We are descended from William). We will be writing about them extensively in the following chapters. In our research we discovered additional siblings. The known children of Thomas and Margarit (Gilhagie) Mclintoch are as follows:

- Jonet, May 12, 1696 — death date unknown

- Michael, born March 10, 1698 — death date before 1709

- James, born March 23, 1701 — death date unknown

- Agnes, born November 12, 1702 — death date unknown

- Elizabeth, September 11, 1705 — death date unknown

- Michael, September 18, 1709 — death date unknown

- William, September 18, 1709 — death date unknown

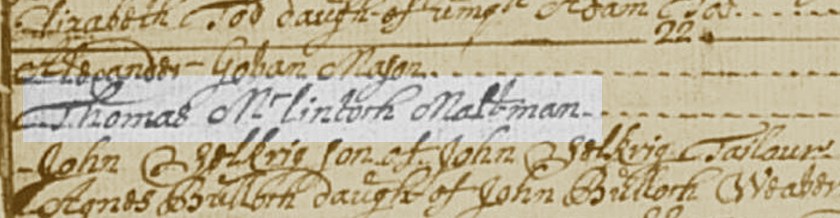

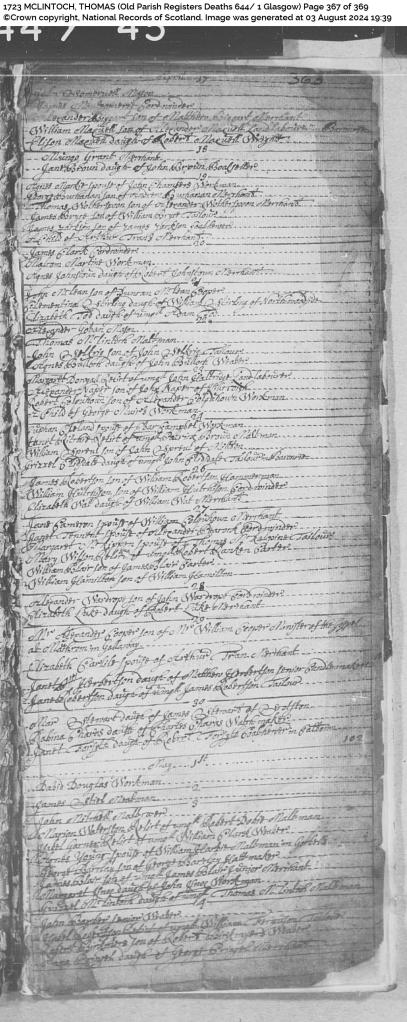

By 1723, Thomas Mclintoch had died. We discovered on the death register that he was what was know as a Maltman. “The name Maltman means a brewer, which is a craft which goes back to prehistoric times in Scotland. By the seventeenth century maltmen or brewers were well established in every town. Their craft symbol of malt shovels and sheaves of corn can still be found on gravestones all over the country”. (Scotland’s A Story to Tell…see footnotes)

In an era when clean water was not necessarily safe enough to drink, everyone drank fermented or distilled beverages like beer or whiskey, because the fermentation process killed the nasty microorganisms. Hence, Brewers were considered important, and it was a protected Guild.

Our ancestors might have been enjoying fermented beverages to pass the time, but much had been going on in Europe which affected their peace and prosperity… (3)

John Calvin Was a Big Interrupter to The Status Quo

For centuries Europe had been struggling with dueling monarchies, fractious wars, and shaky alliances —but the world was slowly changing. Some of the English and Scottish monarchy knew this and had been plotting ways to hold things together through state centralization.

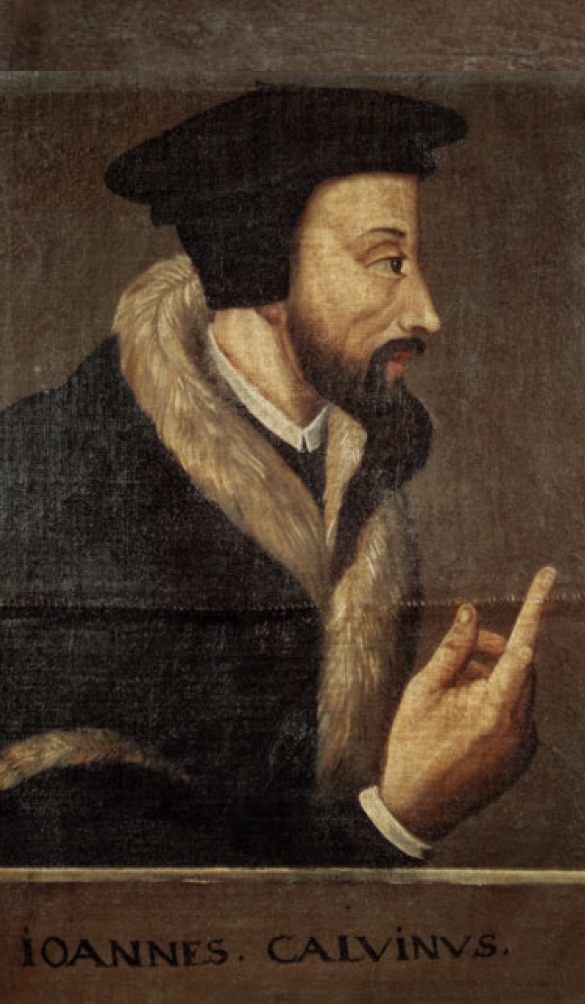

The gist of it is this: The Reformation had brought much change to Europe through the rise of the Protestant religion, greatly influenced by the French theologian John Calvin. “He was a principal figure in the development of the system of Christian theology later called Calvinism, including its doctrines of predestination and of God’s absolute sovereignty in the salvation of the human soul from death and eternal damnation.” (Wikipedia)

For a veeerry looonng time much ado was made about whether you were Protestant, or Catholic. In 1534, the English King, Henry the VIII, wanted to divorce his first wife, Queen Katherine of Aragon, a devote Catholic. The Pope, in Rome disagreed. So Henry got cranky and had all of the Catholics removed, along with their power, because he was mad at the Pope. The English then adopted a form of worship in the Anglican Church, which was technically Protestant, but still looked rather Catholic in its painstaking presentation.

John Calvin, French theologian ((1509-1564), The Houses of Stuart and Orange: King William III (reigned 1689 – 1703), Queen Anne (reigned 1702 – 1707), and then she continued as Queen under The House of Stuart, (reigned 1707 – 1714).

For years afterward, there were still a lot of Catholics in England, Ireland and Scotland. By the reign of James VI and “…he was the last Catholic monarch of England, Scotland, and Ireland. His reign is now remembered primarily for conflicts over religious tolerance, but it also involved struggles over the divine right of kings. He was deposed in 1688, and later that year leading members of the English political class invited William of Orange [a Protestant] to assume the English throne.

*[He was King James VI in Scotland. When he became King of England, after Queen Elizabeth I’s death, he also became King James I].

Until the Union of Parliaments, [when the Scottish and English parliaments merged], the Scottish throne might be inherited by a different successor [a non Protestant] after Queen Anne, who had said in her first speech to the English parliament that a Union was very necessary.” (Wikipedia) Anne’s father was Catholic, but she and her sister Mary were raised Protestant. As writer Hamish MacPherson puts it in The National, “The English nobility’s obsession with securing ‘correct’ succession for Queen Anne overrode all other considerations…” (i.e., they wanted only a Protestant in charge of things).

Long story short, between 1706 and 1707, things were worked out by the Acts of Union, whether people liked it or not.

“The Acts of Union refer to two Acts of Parliament, one by the Parliament of England in 1706, the other by the Parliament of Scotland in 1707. They put into effect the Treaty of Union agreed on July 22, 1706, which combined the previously separate Kingdom of England and Kingdom of Scotland into a single Kingdom of Great Britain. The Acts took effect on 1 May 1, 1707, creating the Parliament of Great Britain, based in the Palace of Westminster”. (Wikipedia)

How did this affect our ancestors living in Scotland? Our Glasgow brewer ancestor, Thomas Mclintoch would have interacted much with the growers of wheat, barley, rye, and corn, because he needed their products to do his craft. Price fluctuations, embargoes, crop failures, taxes, exports to England, etc., would have brought additional stresses… If the Scots had a feeling of autonomy, they were now completely beholden to England. The years leading up to the Acts of Union had been difficult for the Scots. (4)

A Scotsman, An Englishman, and a Volcano, Walk Into a Bar

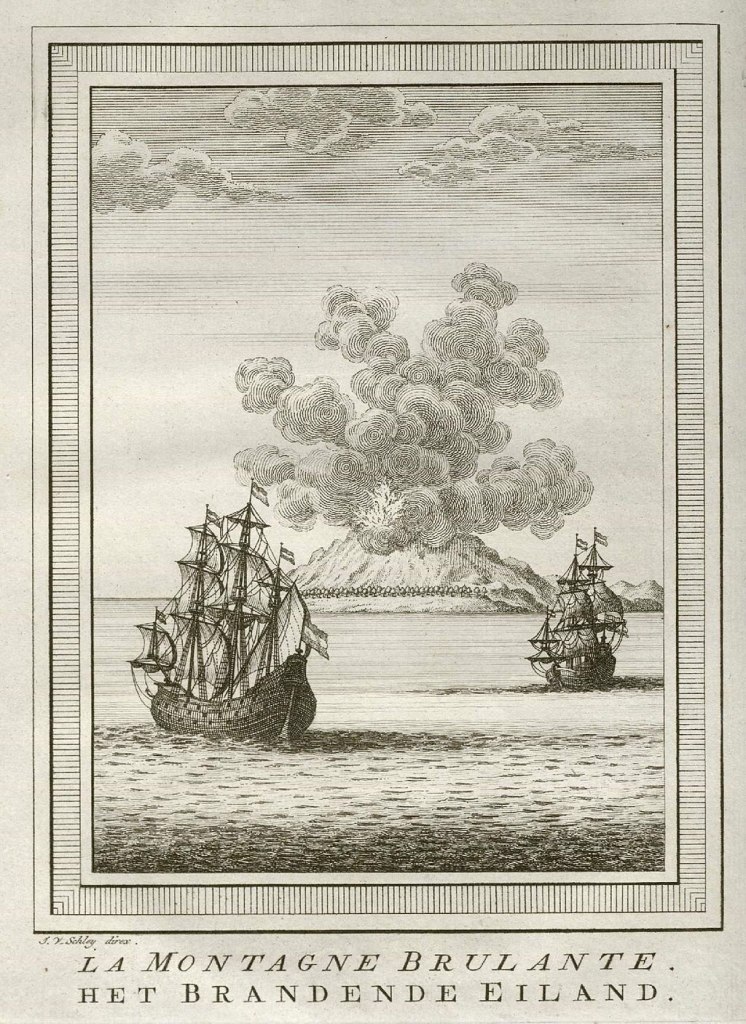

“The Scottish economy was severely impacted by privateers during the 1688–1697 Nine Years’ War and the 1701 War of the Spanish Succession, with the Royal Navy focusing on protecting English ships. This compounded the economic pressure caused by the seven ill years of the 1690s, when 5–15% of the population died of starvation.” (Wikipedia) But this may not have been all that was going on —

From the Daily Mail, “Crop failures that lead to Scotland signing up to the 1707 Acts of Union with England were caused by tropical volcanic eruptions thousands of miles away, scientists have claimed. When the two lava-chambers blew their tops within three years of each other, first in 1693 and then a second in 1695, the Caledonian temperature dipped by about 1.56C across Caledonia. The added cooling meant plants like wheat and barley did not grow properly, leading to a famine that killed up to 15 per cent of the country’s population”.

And from Science magazine, “the second-coldest decade of the past 800 years stretched from 1695 to 1704. Summertime temperatures during this period were about 1.56°C lower than summertime averages from 1961 to 1990, the team will report in a forthcoming issue of the Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research

All of this coincides with two major volcanic eruptions in the tropics: one in 1693 and an even larger one in 1695. The one-two punch likely sent Scotland into a deep chill that triggered massive crop failures and famines for several years, the team speculates”.

(Wood engraving from an English newspaper of 1849, via Alamy).

“The migration of Scot-Irish settlers to America began in the 1680s but did not occur in large numbers until the 1720s. Although the Scottish emigrants, in coming to America, were assured freedom to exercise their Presbyterian religion at a time when the Stuart monarchy favored spreading the Anglican Church throughout the British Isles, the most important motivation for Scottish emigration was economic. (Encyclopedia of North Carolina) (5)

Presbyterianism

Our research on American records has determined that these ancestors followed the Presbyterian line of Protestant faith. In the European world in which they lived, religions had always been sanctioned by the Monarchies, or the Pope, or a combination of the two. The Acts of Union had guaranteed the Scots the right to self-determination in worship, but we believe that they were still a bit wary about believing this right truly existed.

“The word Presbyterian is applied to churches that trace their roots to the Church of Scotland or to English Dissenter groups that formed during the English Civil War.

“The cross many people know as the Presbyterian cross has its roots in the Celtic tradition and the Scottish Reformation. This design emerged in early Christian Ireland and Scotland around the 5th-8th centuries. The circle on the cross is interpreted by some as representing eternity, the sun, or the cycle of life and death”. (See footnotes).

Presbyterian church government was ensured in Scotland by the Acts of Union in 1707, which created the Kingdom of Great Britain. In fact, most Presbyterians found in England can trace a Scottish connection, and the Presbyterian denomination was also taken to North America, mostly by Scots and Scots-Irish immigrants. The Presbyterian denominations in Scotland hold to the Reformed theology of John Calvin and his immediate successors, although there is a range of theological views within contemporary Presbyterianism”. (Wikipedia)

Times were rather tough. There were economic troubles, wars, crop failures, absentee landlords… and religious considerations. We’re certain these ancestors were hearing reports about new opportunities in America. It was probably due to the lack of opportunity for economic advancement and a desire to break free from the hierarchical restrictions of Scottish culture which made the younger McClintocks seek to move on. (6)

In the next chapter we will write about the twin sons Michael and William McClintock and their move to America.

Following are the footnotes for the Primary Source Materials,

Notes, and Observations

If you are a stickler for details as we are…

(1) — three records

Playing Detective, 1950s (photo)

https://www.bridgemanimages.com/en/noartistknown/playing-detective-1950s-photo/photograph/asset/8677960

Note: For the detective photo.

Shires of Scotland

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shires_of_Scotland

Note: For the data.

Dunbartonshire

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dunbartonshire

Note: For the data.

The Central Belt of Scotland

(2) — one record

The National Archives

The North Part of Great Britain Called Scotland.

“With Considerable Improvements and many Remarks not Extant in any Map.

According to the Newest and Exact Observations”

by Herman Moll, Geographer, 1714

https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/jacobite-1715/geographers-map-scotland/

Note: For the map image.

The Thomas Mclintoch Family of Glasgow

(3) — seventeen records

Thomas Mclintoch

in the Scotland, Select Births and Baptisms, 1564-1950

https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/9444758:60143?tid=&pid=&queryId=29665721-b3bc-46cf-81e3-90eaeb046c41&_phsrc=doN9&_phstart=successSource

Note: For the data.

and here:

Thomas Mclinto

in the Scotland, Select Births and Baptisms, 1564-1950

https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/1515775:60143?tid=&pid=&queryId=1df482c4-0a37-46c3-97a7-ee527c0ee257&_phsrc=HNd3&_phstart=successSource

Note: For the data.

and here:

Scotlands People

https://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/saved-images/N1pTU1l2d0U1WmNNMDMzdFlNUk0waHRlNXR4dUlVUTNxY0lOdXVZWlBrTG4vTzhRZk9rZkx5NWtOOWdLeld3PQ==

Note: For the death information.

(Image courtesy of Scotlands People).

Glasgow Cathedral

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glasgow_Cathedral

Note: For the text.

Michael Mclintoche

in the Scotland, Select Births and Baptisms, 1564-1950

https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/12584581:60143?tid=&pid=&queryId=dd9446ff-1e7a-440f-9eb5-41145af4a704&_phsrc=PXe62&_phstart=successSource

Note: For the data — who the parents are, Thomas Mclintoche and Margarit Gilhagie.

Michael Mcclintoch

in the Scotland, Select Births and Baptisms, 1564-1950

https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/7823422:60143

and

William Mcclintoch

in the Scotland, Select Births and Baptisms, 1564-1950

https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/3584815:60143

Note: For the data.

Jonet, 12 May 1696

in the Scotland, Select Births and Baptisms, 1564-1950

https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/7051421:60143

Note: For the data.

James, 23 Mar 1701

in the Scotland, Select Births and Baptisms, 1564-1950

https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/20653534:60143

Note: For the data.

Agnes, 12 Nov 1702

in the Scotland, Select Births and Baptisms, 1564-1950

https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/11591501:60143

Note: For the data.

Eliz. Mcclintock

in the Scotland, Select Births and Baptisms, 1564-1950

https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/12445644:60143

Note: For the data.

Scotlands People 1723 Death Register record

https://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/saved-images/N1pTU1l2d0g0SjBNMDMzdFlNSkF3UnRlNXR4dUlVUTNxY0lOdXVZWlBrTGovTzhRZk9nYkxDNWtOOWdLeld3PQ==

Note: For the data — Thomas McClintock, which also lists his profession as Maltman.

A Story to Tell, Pubs & Bars

The Maltman, A Story of Architecture and History

https://www.scotlandspubsandbars.co.uk/location/the-maltman/#:~:text=The%20name%20Maltman%20means%20a,gravestones%20all%20over%20the%20country.

Note: For the text.

The Tradeshouse of Glasgow

Maltmen

Note: For the text.

History of Malting

https://www.brewingwithbriess.com/malting-101/history-of-malting/

Note: For Malt floor image.

Brief History of the Incorporation of Maltmen of Glasgow

https://www.tradeshousemuseum.org/maltmen.html

Note: For the guild symbol.

Our Story

https://www.arranwhisky.com/about/our-story

Note: For the Master Distiller image.

John Calvin Was a Big Interrupter to The Status Quo

(4) — seven records

John Calvin

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Calvin

Note: For the data.

Kunstkopie.de

Portrait of John Calvin (1509-64)

Attributed to the Swiss School

https://www.kunstkopie.de/a/swiss-school/portrait-of-john-calvin-1-2.html

Note: For his portrait.

James II of England

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_II_of_England

Note: For his portrait.

List of English Monarchs

Houses of Stuart and Orange

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_English_monarchs

Note: For their portraits.

Queen Anne

File:Dahl, Michael – Queen Anne – NPG 6187.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dahl,Michael–Queen_Anne-_NPG_6187.jpg

Note: For her portrait.

This is How Famine Forever Changed Scottish History

by Hamish MacPherson

https://www.thenational.scot/news/18626007.famine-forever-changed-scottish-history/

Note: For the text.

Acts of Union 1707

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Acts_of_Union_1707

Note: For the text and the Royal Crest of Parliament artwork for both countries.

A King, A Queen, and a Volcano, Walk Into a Bar

(5) — five records

How Volcanoes Helped Create Modern Scotland: Crop famine that led to country signing up to the 1707 Acts of Union with England…

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-7766021/Crop-famine-lead-Scotland-signing-Union-caused-tropical-volcano.html

Note: For the text.

How a Volcanic Eruption Helped Create Modern Scotland

https://www.science.org/content/article/how-volcanic-eruption-helped-create-modern-scotland?rss=1?utm_source=digg

Note: For the text.

Complexity in Crisis: The volcanic cold pulse of the 1690s and the consequences of Scotland’s failure to cope

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0377027319303087

Note: For the text.

The Royal Library of the Netherlands

View of Gunung Api

by Pierre d’ Hondt and Jacobus van der Schley, circa 1758

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:AMH-8034-KB_View_of_Gunung_Api.jpg

Note: For the volcano illustration from the Atlas of Mutual Heritage.

Encyclopedia of North Carolina

Scottish Settlers

https://www.ncpedia.org/scottish-settlers

Note: For the text.

Alamy

Miss Kennedy distributing clothing at Kilrush

(Wood engraving from an English newspaper of 1849, via Alamy).

https://www.alamy.com/stock-photo-irish-potato-famine-1846-7-nmiss-kennedy-distributing-clothing-at-95413912.html

Note: For the illustration.

Presbyterianism

(6) — three records

Presbyterianism

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Presbyterianism

Note: For the text.

St. Charles Avenus Presbyterian Church

A New Pilgrimage to Scotland

https://www.scapc.org/scotland/

Note: For the Contemporary illustration of the Scottish Presbyterian Cross.

First United Presbyterian Church

The Presbyterian Cross

https://www.fupcfay.org/the-presbyterian-cross/

Note: For the text regarding the Scottish Presbyterian Cross