This is Chapter Seven of seven. It is the last of our opening chapters on The Pilgrims. So far we have covered topics such as — how they thought differently than we do today, British colonization, their experiences in Holland, the Mayflower, Plimoth Plantation, and the Native Peoples they encountered. Finally, we get to the part that most of us know, the Thanksgiving celebration. Like a great meal, pass the plate please, because there’s always more to share.

The Thanksgiving holiday is a national ritual that has moved like a resonant wave through American culture for more than 150 years. Iconic images such as those by painter Norman Rockwell have impressed generations, including our own family.

March 6, 1943. (Image courtesy of the Saturday Evening Port archives).

Freedom From Want

“One of Norman Rockwell’s most well known and adored paintings, ‘Freedom from Want’ was never actually on the cover of the magazine. It appeared as an inside illustration, along with the three other images that represented President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms: Freedom of Speech, Freedom of Worship, and Freedom from Fear. Hundreds of variations of this image have been created, including ones for our magazine featuring The Muppets and The Waltons.” (The Saturday Evening Post)

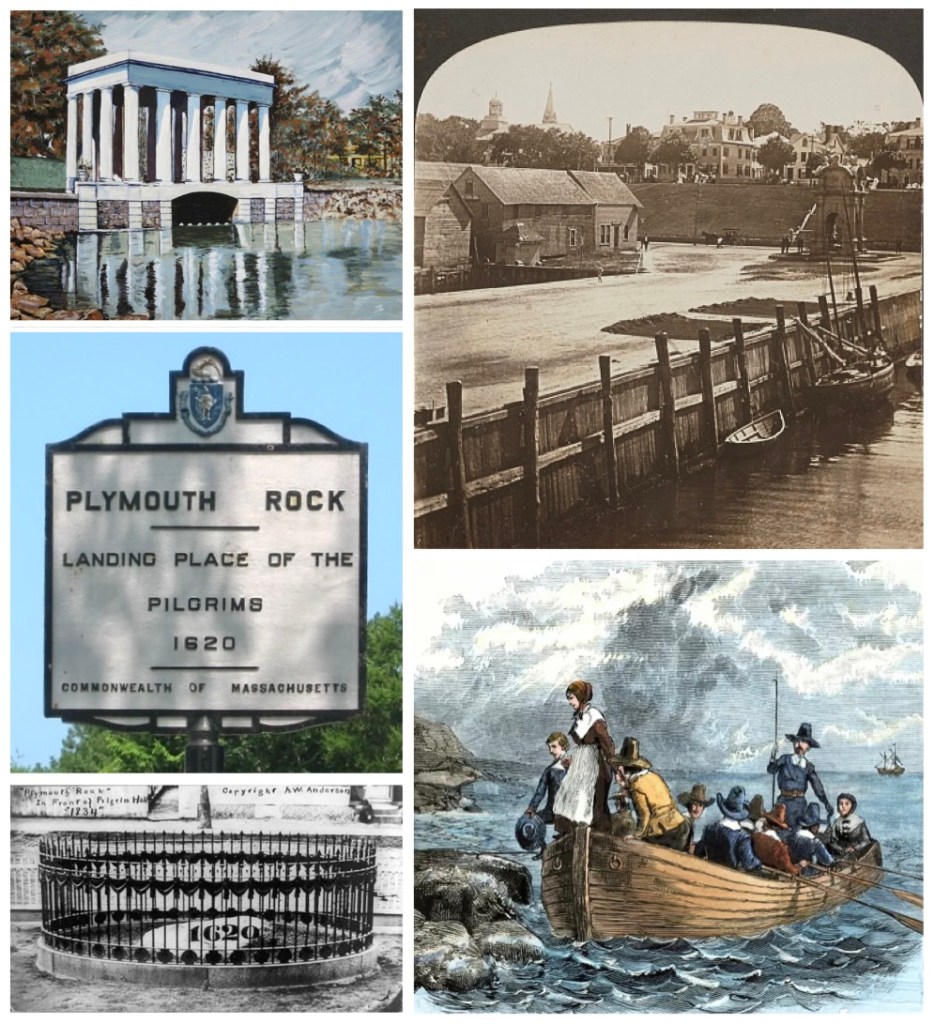

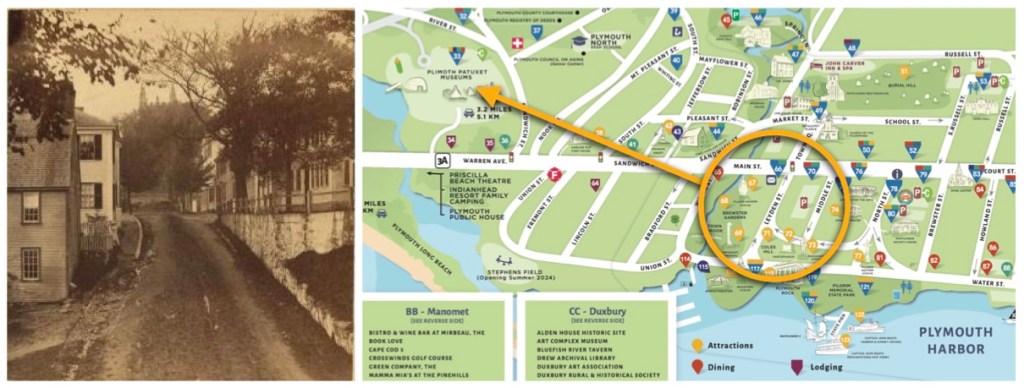

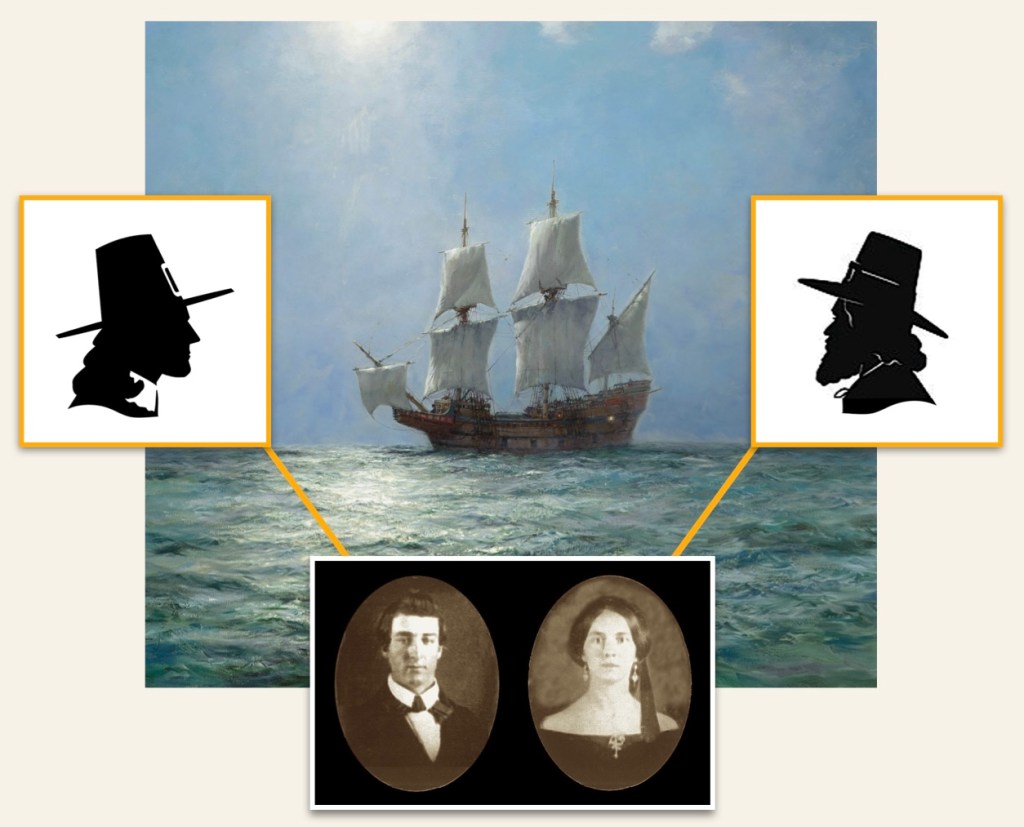

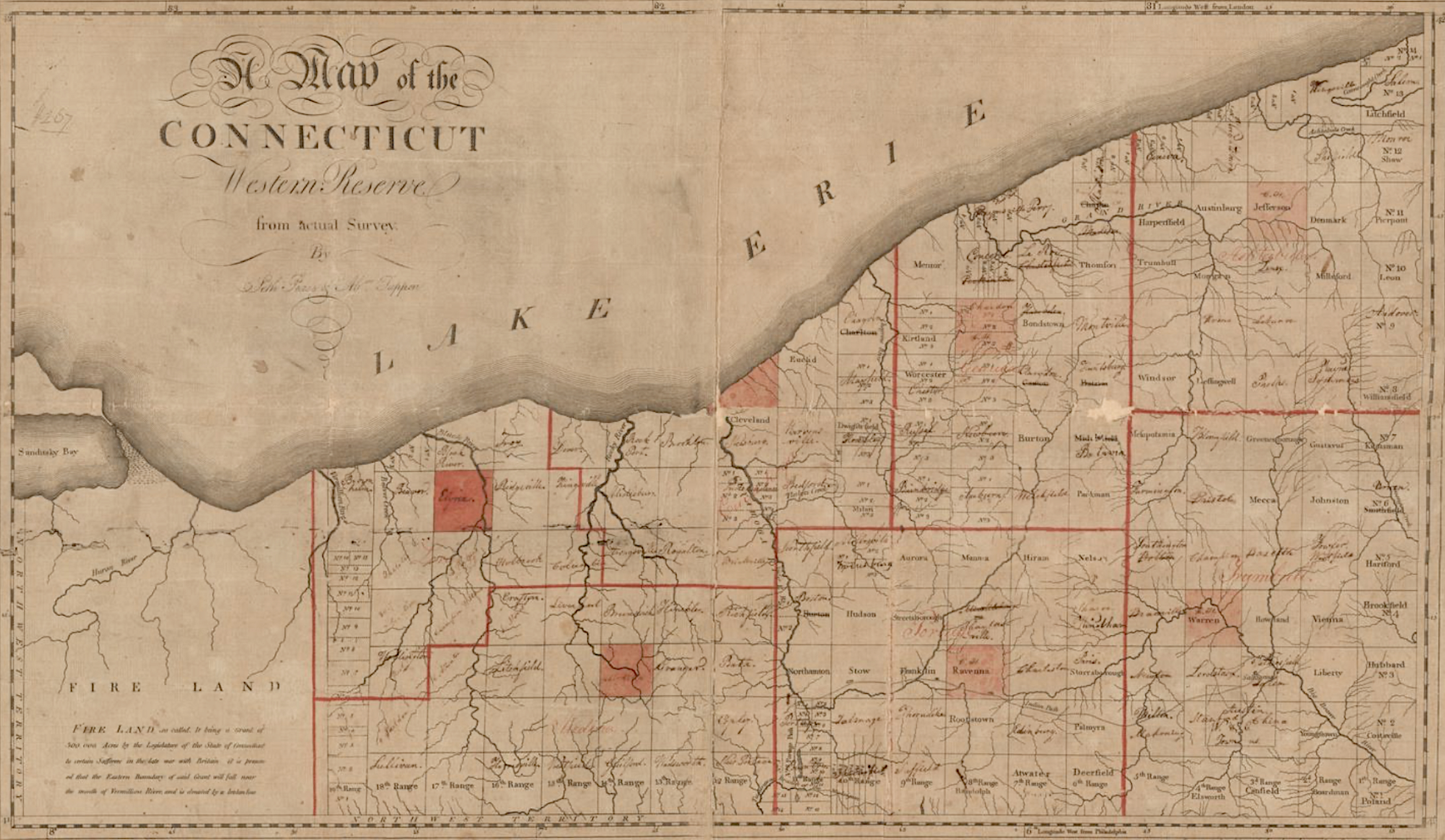

The Pilgrims arrived at Cape Cod Bay over 400 years ago. That has been a lot of time for some mythology about the first Thanksgiving to have developed — an event at which two of our ancestors were present. Some myths and rituals are good, because they bring all of us together. We think it will be interesting to look at and write a bit about, both this mythology and the actual history.

Myths are the body of legends and stories that belong to our different societies. Occasions such as wedding ceremonies, funerals, baptisms, Bar Mitzvah, church services, college graduations, Super Bowl, and Heineken Cup (Rugby) are all examples of the various types of rituals that take place during our normal lives.

Writer Brian Leggett,

It is these myths and rituals that give our societies some meaning and contribute to stability. Indeed, one could say that stability requires its myths and rituals.

writing on Joseph Campbell’s book, The Power of Myth

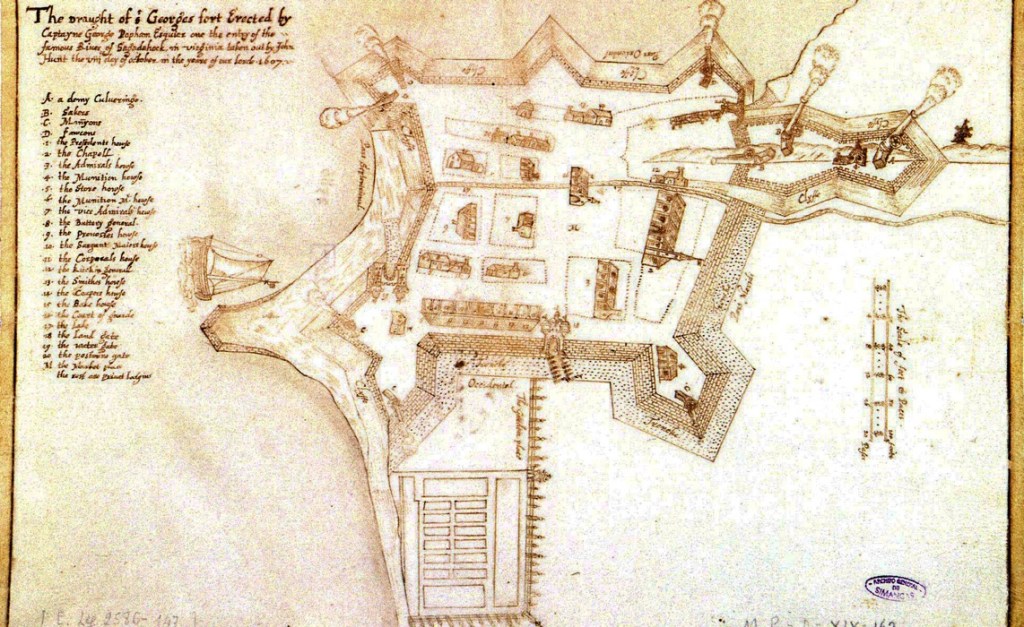

“For American culture, the story of the Pilgrims, including their “first Thanksgiving” feast with the local Native Americans, has become the ruling creation narrative, celebrated each November along with turkey, pumpkin pie, and football games. The Pilgrims and Plymouth Rock have eclipsed the earlier 1607 English settlement at Jamestown, Virginia, as the place where America was born.” (National Endowment For The Humanities – NEFTH) (1)

What Happened In That First Winter

Before we can get to the first Thanksgiving celebration we need to pass through the devastating winter which the Saints and Strangers experienced. When they disembarked, it was already a troublesome experience. “With passengers and crew weakened by the voyage and weeks exploring Cape Cod, the Mayflower anchored in Plymouth harbor in late December 1620. The weather worsened, and exposure and infections [began to] take their toll. (PBS)

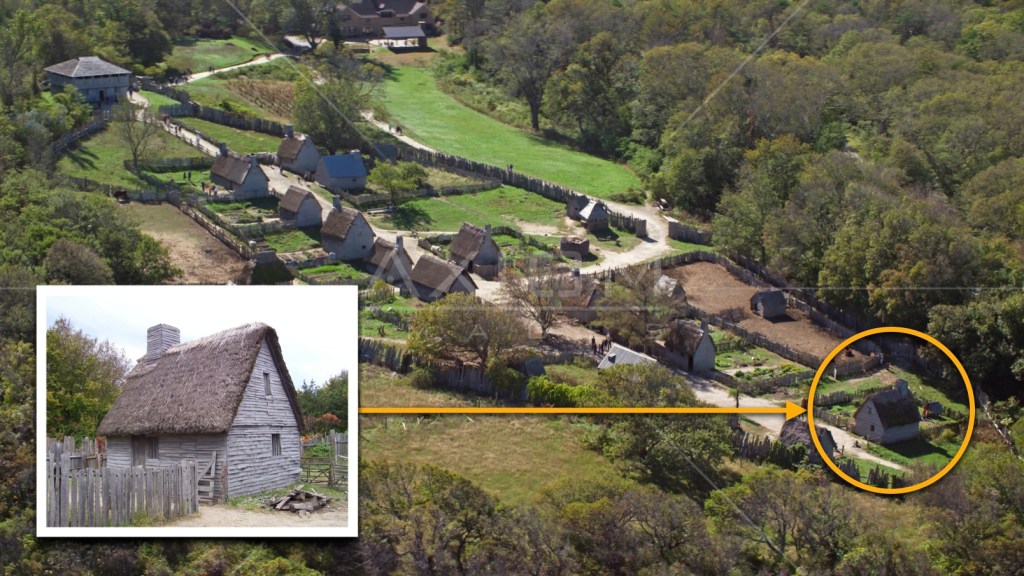

Immediate decisions were made as to where to begin with the development of structures for shelter. This required felling trees and making their own lumber. — “First to be built was a Common House which would have several huts around it. Then there would be living quarters built for the settlers. There would be a total of 19 lots. Because of the hardships that the settlers had to endure in the coming months, the Common House had to be used as living quarters and a hospital. Just as the construction of the Common House began, a storm came along which featured snow that changed to rain. During the next three weeks, there were a number of storms that moved through while producing rain, snow, and sleet. Many settlers lived on the Mayflower and left the ship [only] to work until March when more dwellings were constructed in earnest.” (NY NJ PA Weather – NYNJPA)

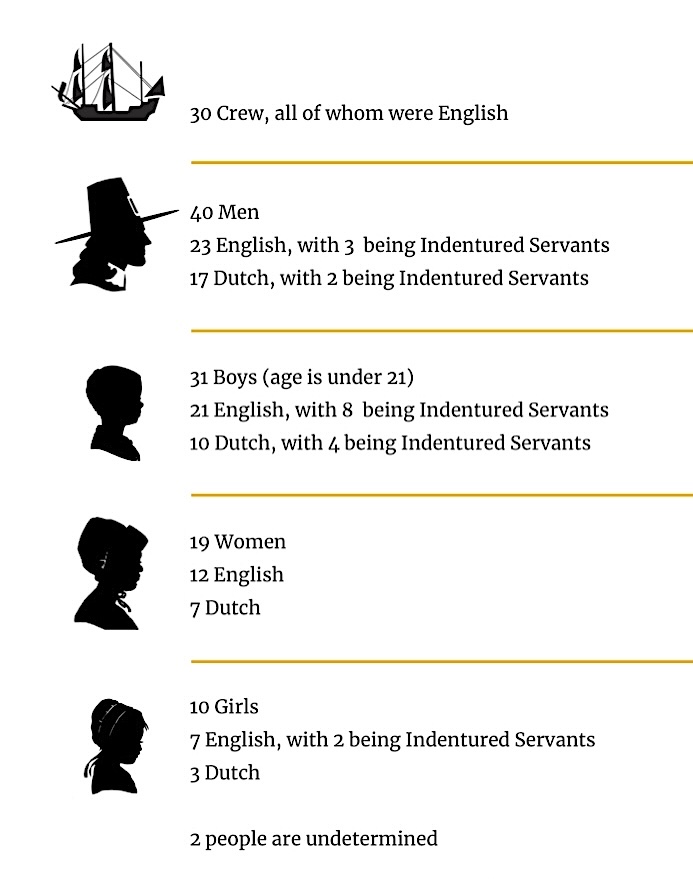

“Many of the colonists [had fallen] ill. They were probably suffering from scurvy and pneumonia caused by a lack of shelter in the cold, wet weather. Although the Pilgrims were not starving, their sea-diet was very high in salt, which weakened their bodies on the long journey and during that first winter. As many as two or three people died each day during their first two months on land. Only 52 people survived the first year in Plymouth. When the Mayflower left Plymouth on April 5, 1621, she was sailed back to England by only half of her crew.” (Plimoth Pautexet)

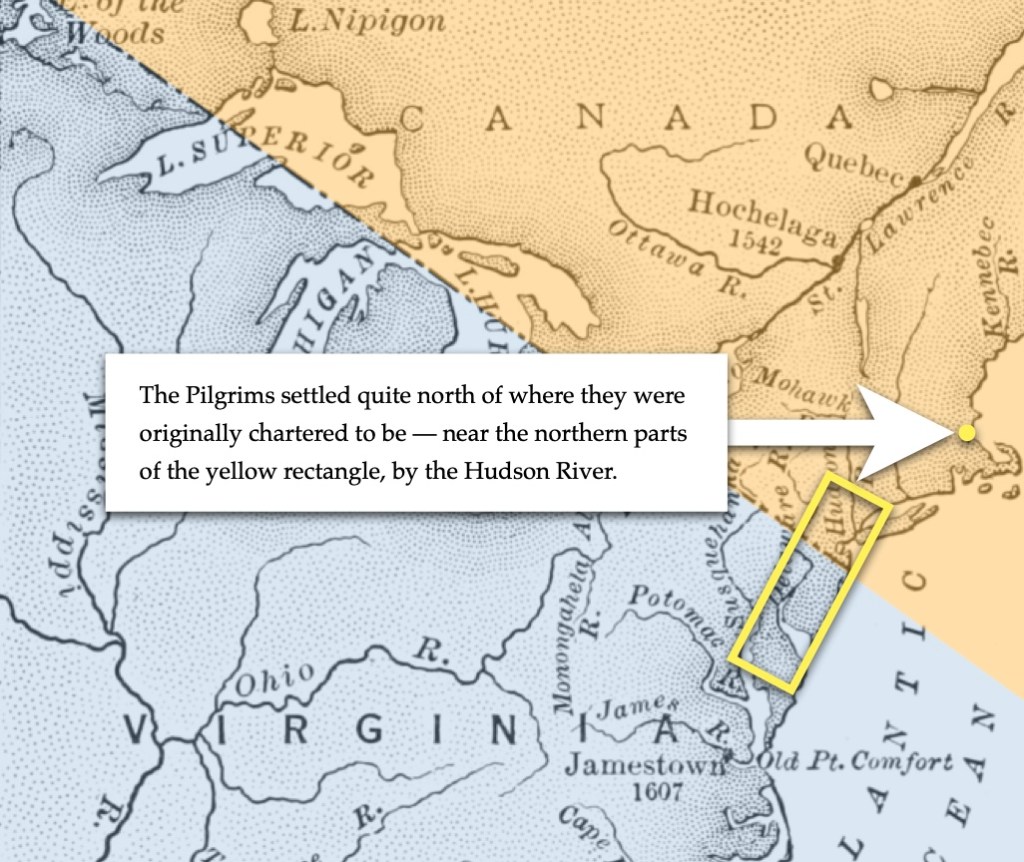

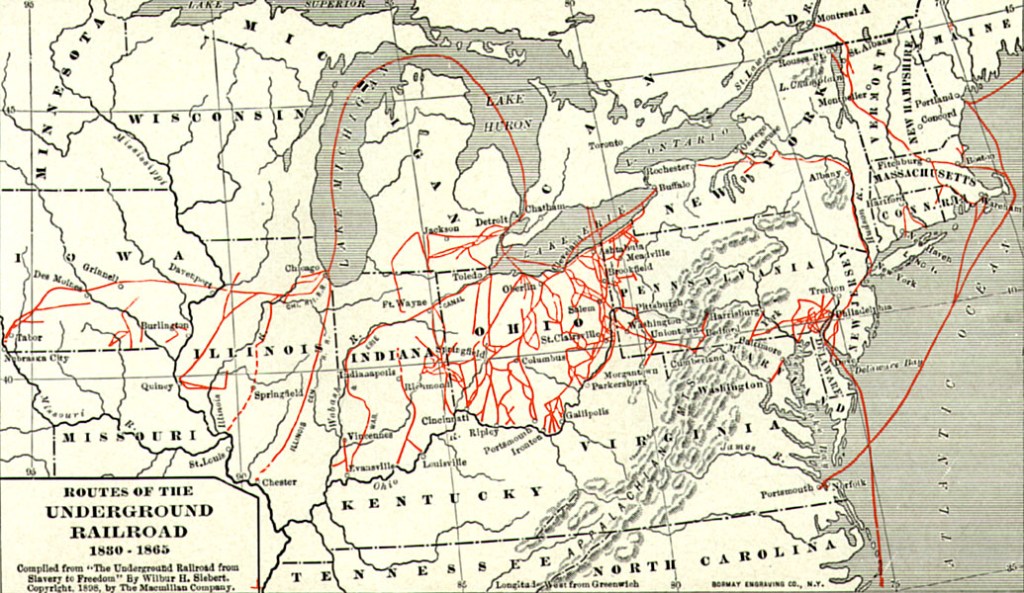

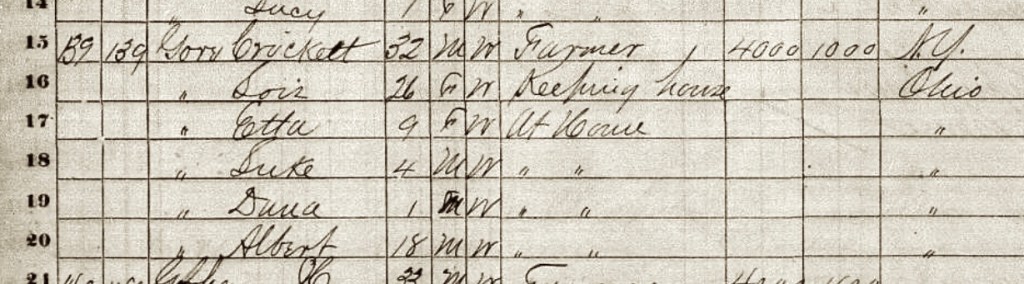

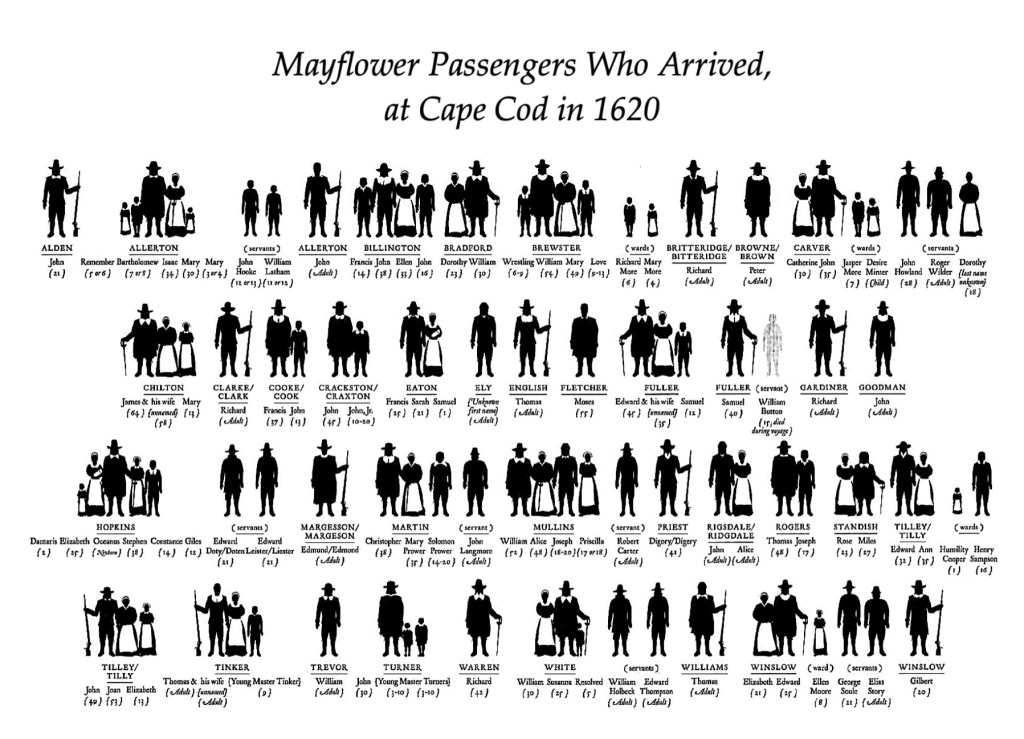

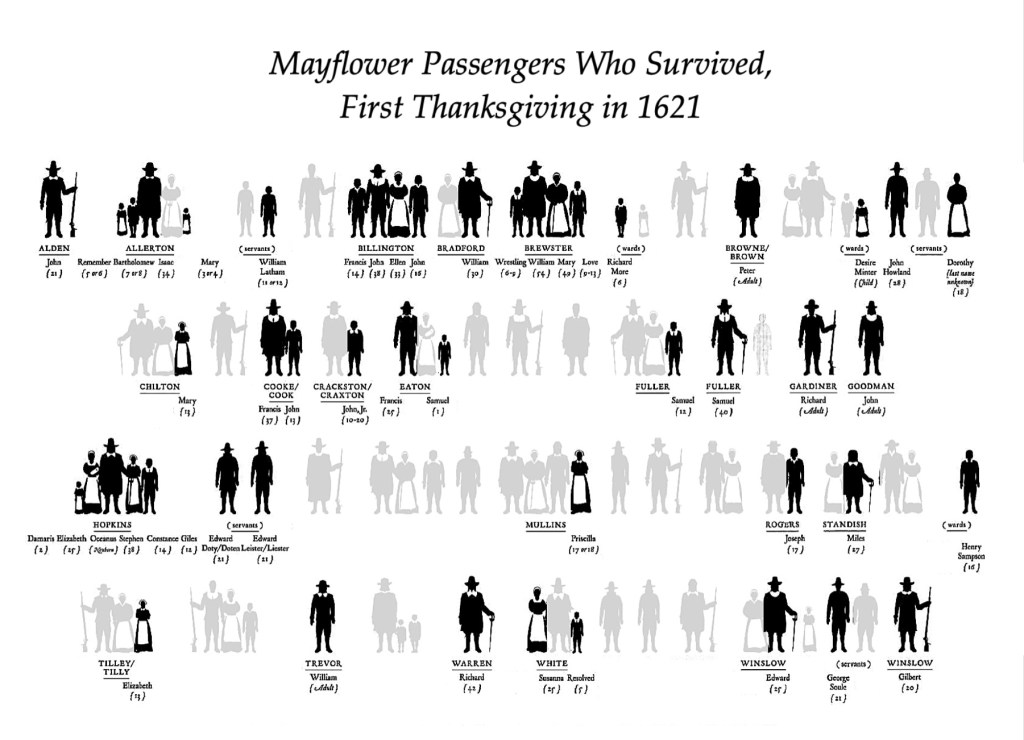

By the spring of 1621, about half of the Mayflower’s passengers and crew had died. We obtained these charts from the Pilgrim Hall Museum, and they are perfect for explaining quite clearly what a difference one year made in their lives.

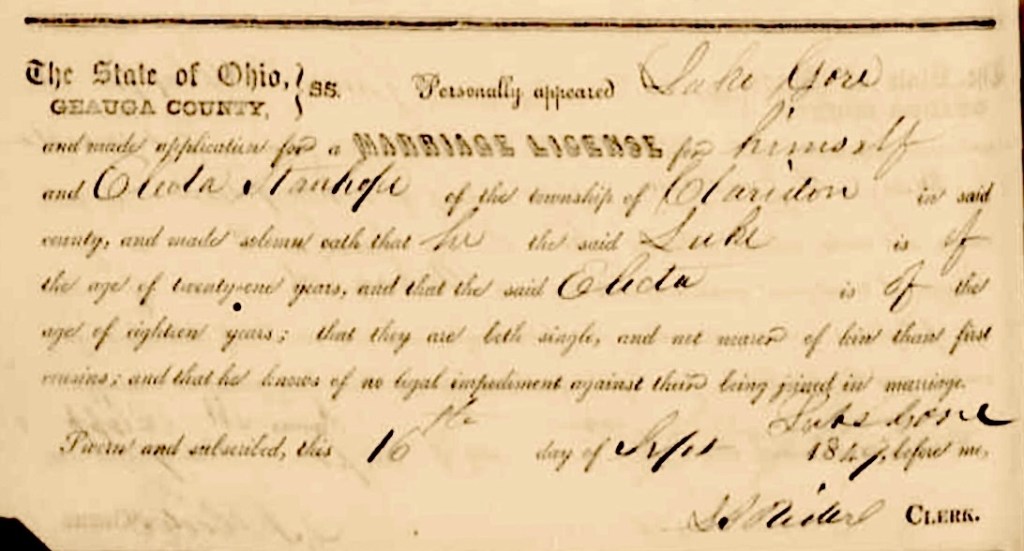

William Bradford kept a registry recording those who had passed. The Plymouth Colony Archive Project shares his entry below. On March 24, 1621 (only three months after they arrived), he wrote —

Elizabeth Winslow: March “Dies Elizabeth, the wife of Master Edward. This month, Thirteen of our number die.”

“And in three months past, die Half our Company. The greatest part in the depth of winter, wanting houses and other comforts; being infected with the scurvy and other diseases which their long voyage and unaccommodate condition bring upon them. So as there die sometimes two or three a day. Of one hundred persons, scarce 50 remain. The living scarce able to bury the dead; the well not sufficient to tend the sick: there being in their time of greatest distress but six or seven who spare no pains to help them. Two of the seven were Master Brewster, their reverend Elder, and Master Standish the Captain.

The like disease fell also among the sailors; so as almost Half their company also die, before they sail.”

(See footnotes — Deetz and Mayflower Society)

“Of the eighteen women who began the journey, only five (Susanna White, Eleanor Billington, Elizabeth Hopkins, Katherine Carver, and Mary Brewster) were alive by the spring of 1621. Of these 5 women, Katherine Carver, wife of Plimoth’s first governor John Carver, would not live to see the year’s end. William Bradford writes that John Carver died in April 1621, and Katherine “his wife, being a weak woman, died within five or six weeks after him.”

“About a year after the arrival of the Mayflower, [around the time of the first Thanksgiving] the ship Fortune reached Plimoth bringing more settlers in November 1621. Amongst its passengers there were only two women, meaning this small contingent of adult women were often spread quite thin between the colony’s domestic duties.” (Mayflower Society) (2)

To Celebrate With A Harvest Feast

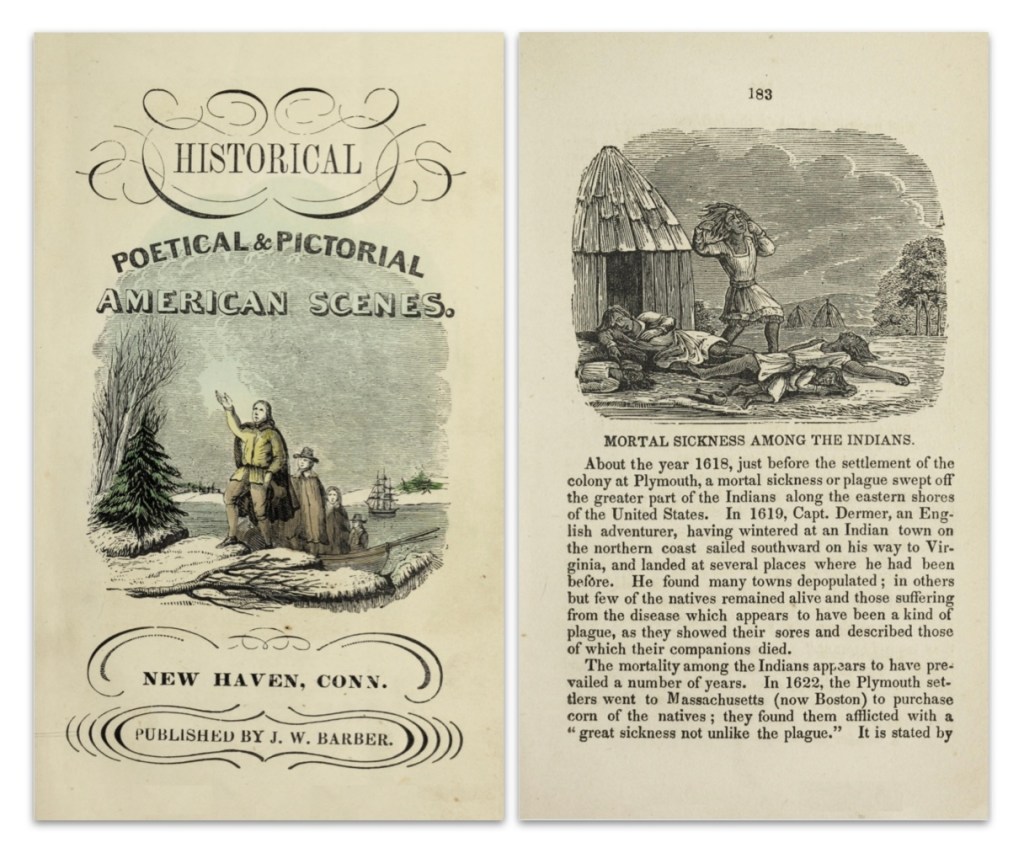

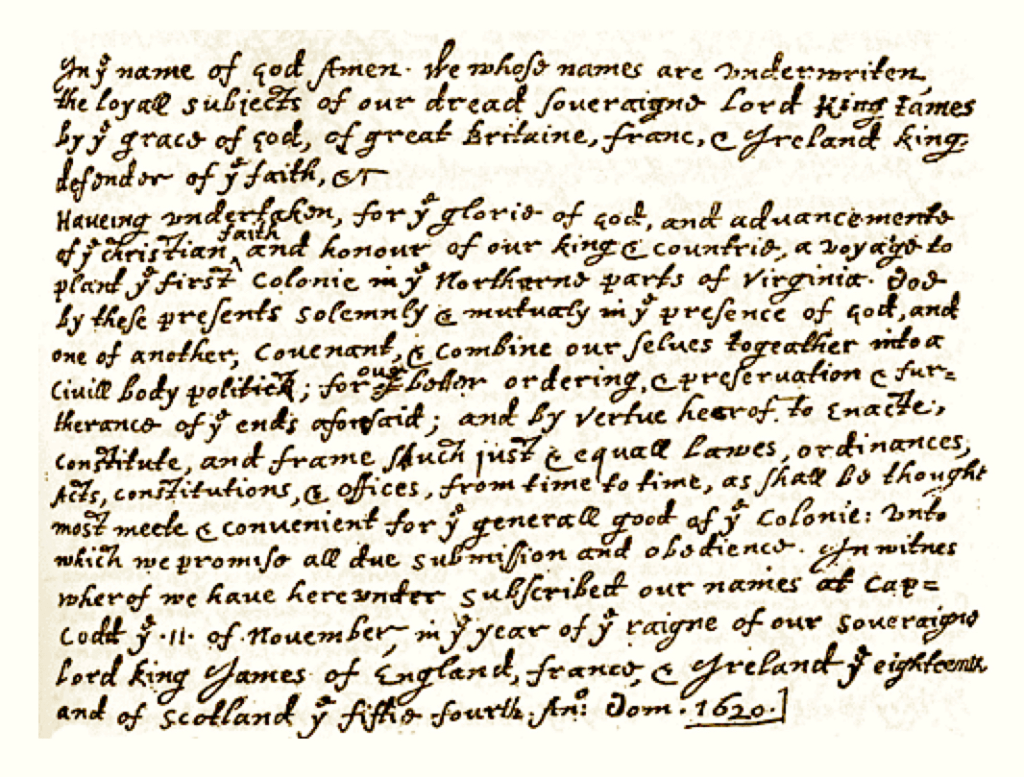

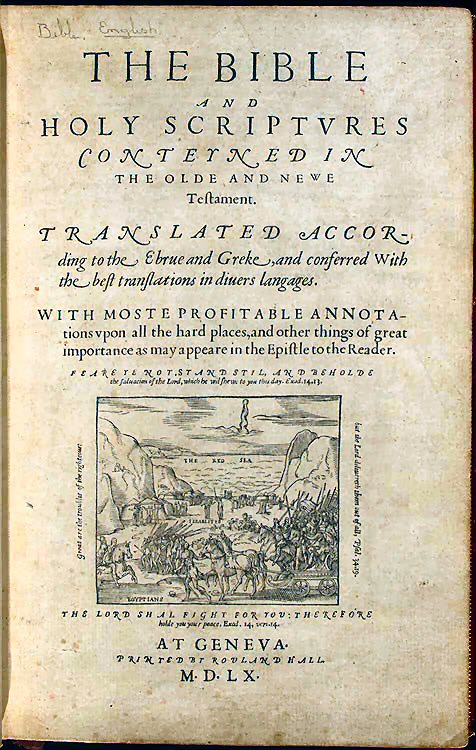

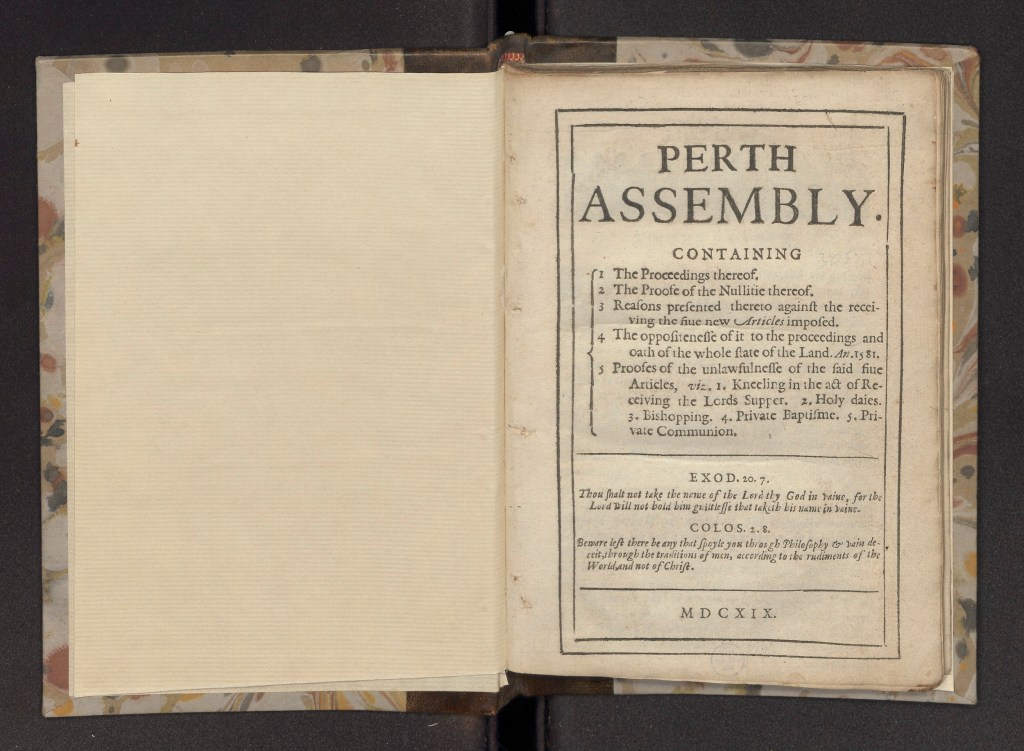

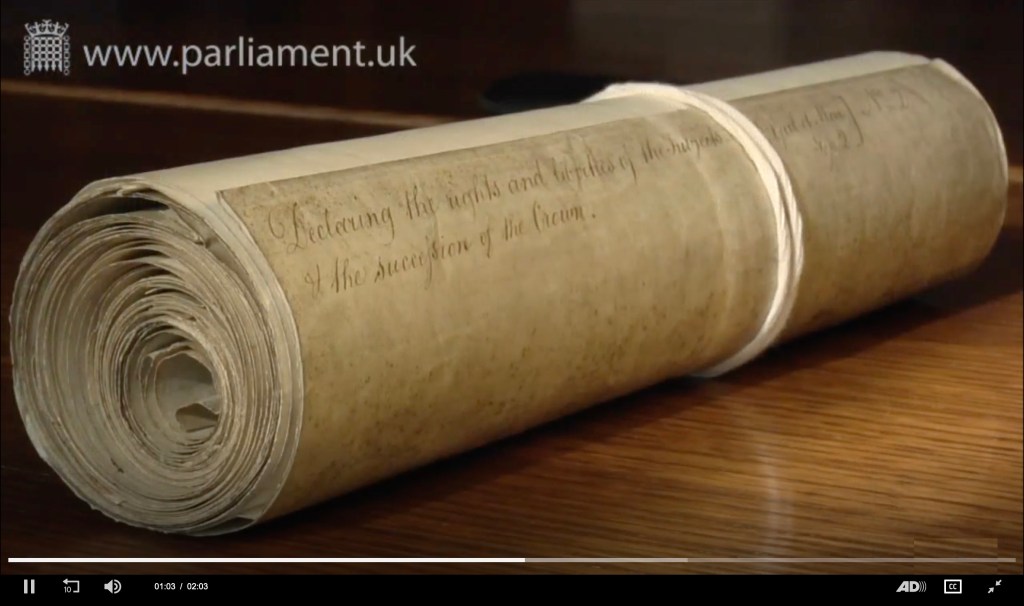

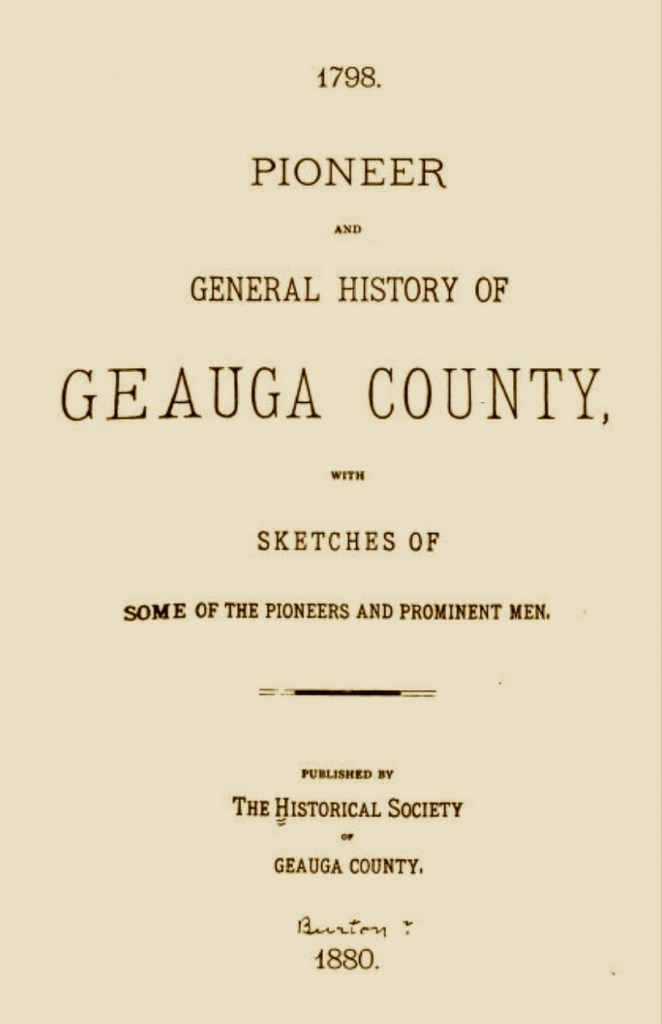

The Thanksgiving holiday has not existed for 400+ years as many people likely assume. In fact, for a long period of time it was a forgotten event. One of the first places it was mentioned is a small book we referred to in the chapter, The Pilgrims — A Mayflower Voyage.

In fact, “as autumn came, the Pilgrims gathered to in a ‘special manner rejoice together after we had gathered the fruit of our labors,’ wrote one of their number, Edward Winslow.” This same event was held again in 1623, but after that, there are no further records of it. (NEFTH)

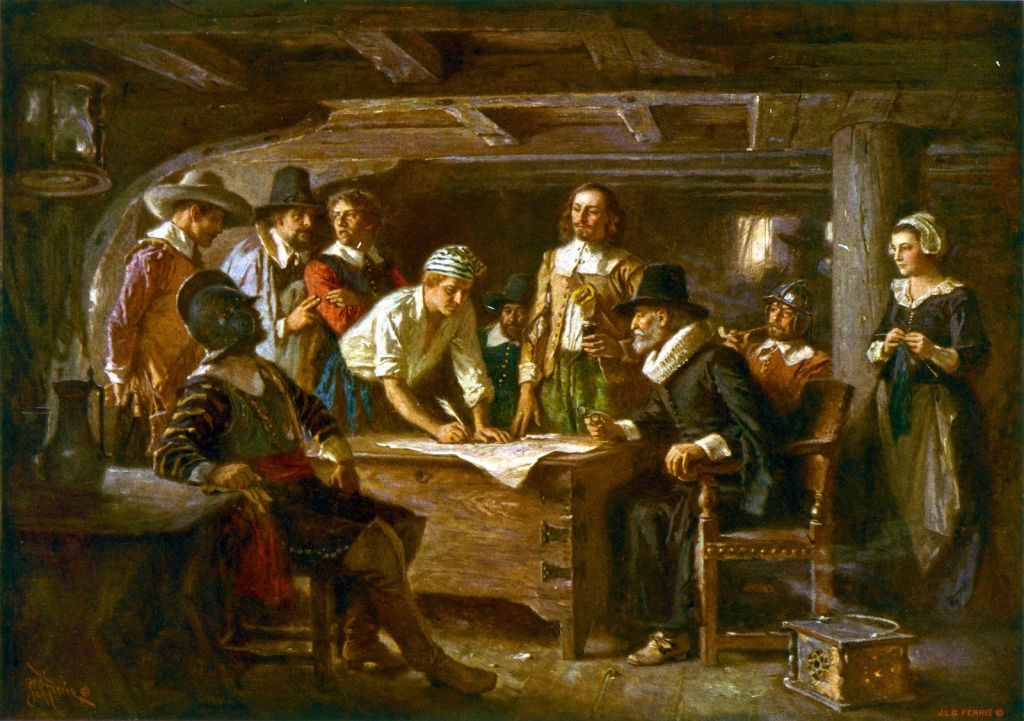

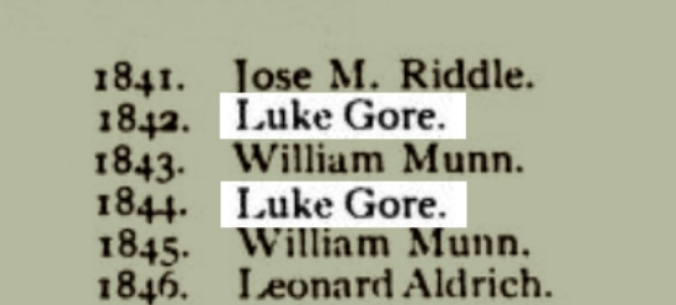

Writer Joshua J. Mark in the World History Encyclopedia, helps us to understand the context of this period in the early 1620s: “The story of the First Thanksgiving comes from only two sources initially: Bradford and Winslow’s ‘Mourt’s Relation’, which gives a detailed account. The book seems to have been an initial success before going out of print and was only brought back to public notice in 1841.

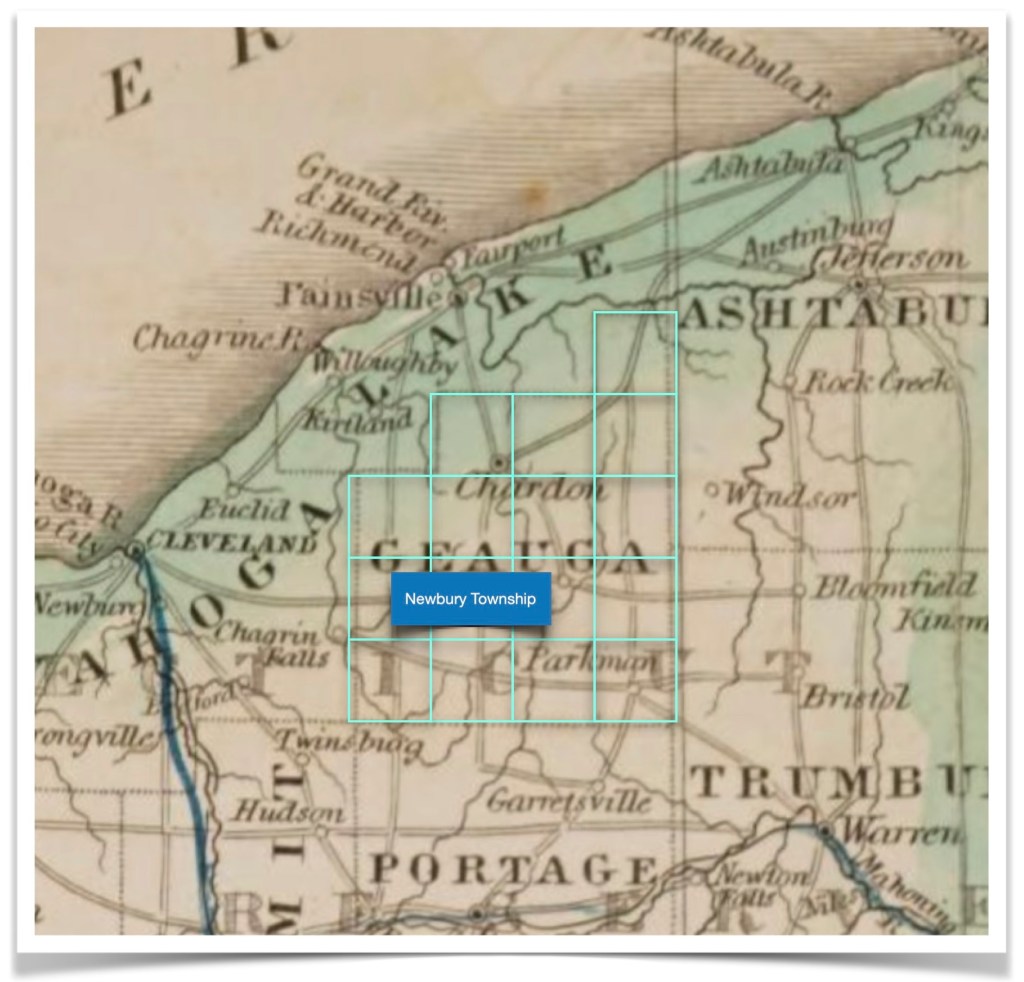

By the fall of 1621, with Squanto’s [and Samoset’s] help, the colonists were able to bring in a good crop and had been shown the best hunting grounds and fishing streams. The colonists decided to celebrate with a harvest feast which has since been defined as the First Thanksgiving.

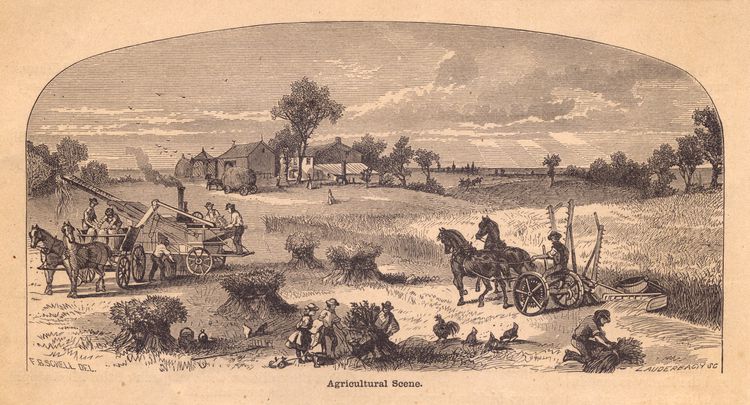

A Popular History of the United States, by William Cullen Bryant, circa 1876.

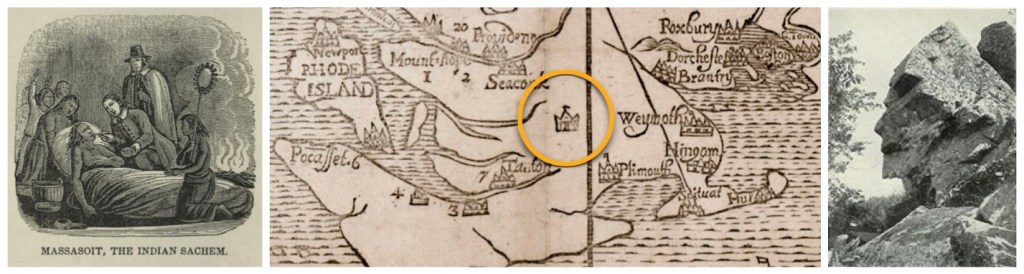

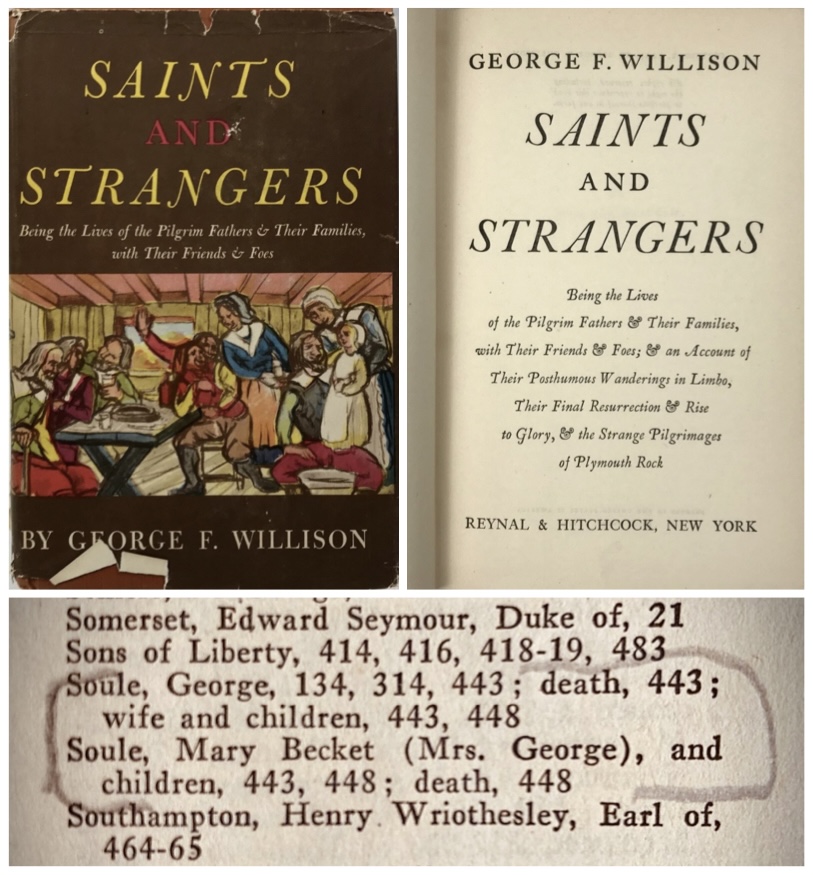

The narrative of the event is usually given along the lines provided by the scholar George F. Willison in his 1945 ‘Saints and Strangers: Being the Lives of the Pilgrim Fathers & Their Families, with Their Friends and Foes’, which is loosely based on Bradford’s and Winslow’s earlier account:

As the day of the harvest festival approached, four men were sent out to shoot waterfowl, returning with enough to supply the company for a week. Massasoit was invited to attend and shortly arrived – with ninety ravenous braves! The strain on the larder was somewhat eased when some of these went out and bagged five deer. Captain Standish staged a military review, there were games of skill and chance, and for three days the Pilgrims and their guests gorged themselves on venison, roast duck, roast goose, clams and other shellfish, succulent eels, white bread, corn bread, leeks and watercress and other “sallet herbes”, with wild plums and dried berries as dessert – all washed down with wine, made of the wild grape, both white and red, which the Pilgrims praised as “very sweete and strong”. At this first Thanksgiving feast in New England, the company may have enjoyed, though there is no mention of it in the record, some of the long-legged “Turkies” whose speed of foot in the woods constantly amazed the Pilgrims.

Hand-colored woodcut of a 19th-century illustration.

(Illustration courtesy of North Wind Picture Archives).

Bradford’s Of Plymouth Plantation, which references the event in more general terms. (It was brought back into print in 1856). Bradford writes:

They began now [fall of 1621) to gather in the small harvest they had, and to prepare their houses for the winter, being well recovered and in health and strength and plentifully provisioned; for while some had been thus employed in affairs away from home, others were occupied in fishing for cod, bass, and other fish, of which they caught a good quantity, every family having their portion. All summer there was no want. And now, as winter approached, wild fowl began to arrive [and] they got abundance of wild turkeys besides venison. (Book II. ch. 2)

Harvest time had now come, and then instead of famine, God gave them plenty, and the face of things was changed, to the rejoicing of the hearts of many for which they blessed God. And the effect of their particular planting was well seen, for all had, one way or another, pretty well to bring the year about, and some of the abler sort and more industrious had to spare, and sell to others, in fact, no general want or famine has been amongst them since, to this day. (Book II. ch. 4) (3)

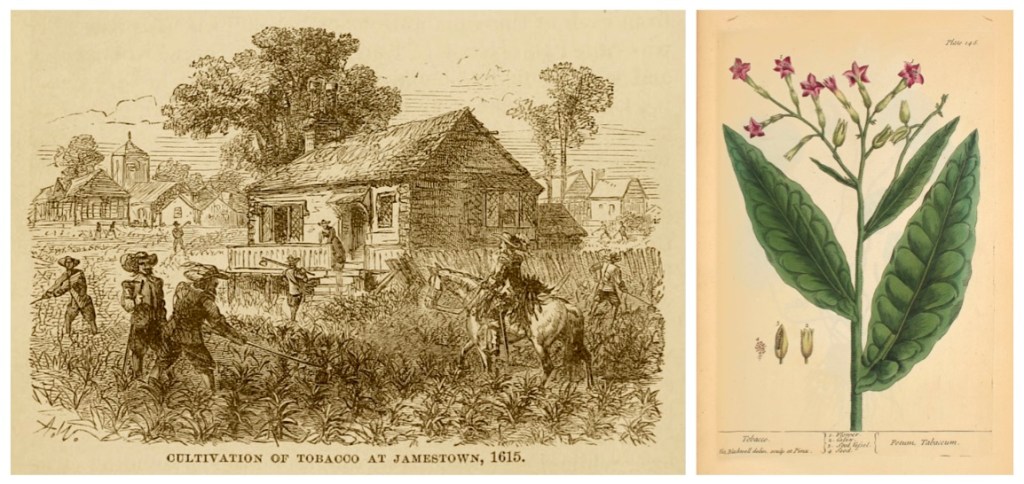

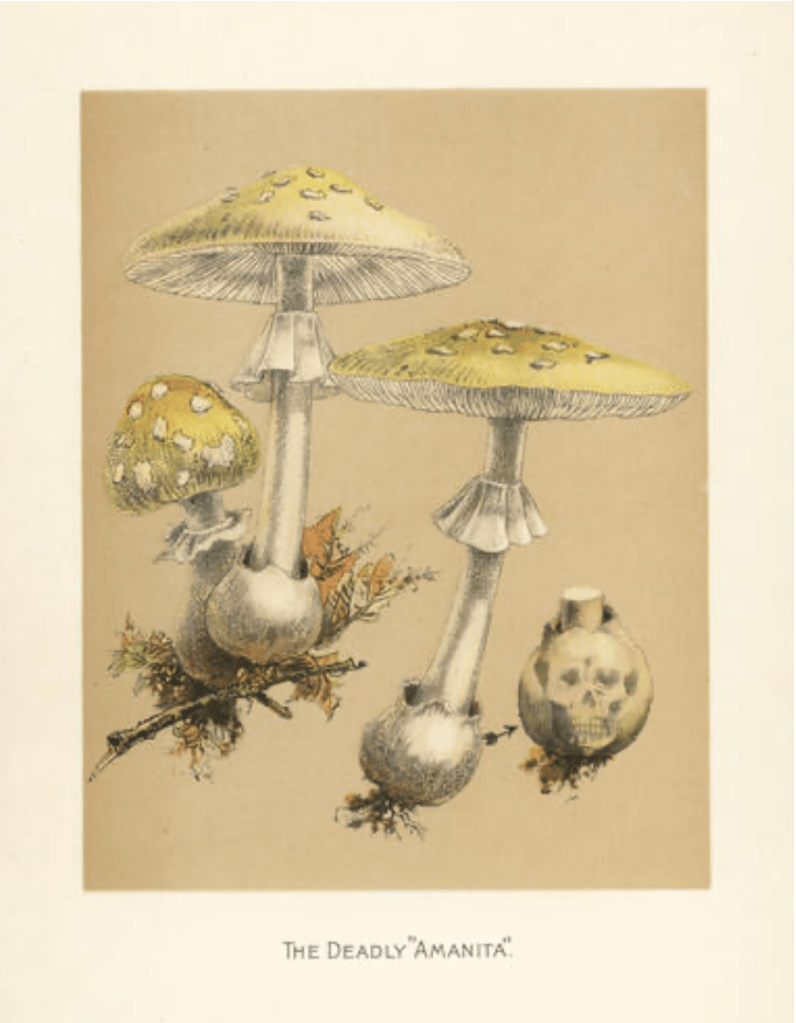

What Was Really On The Menu?

Writer Joshua J. Mark continues: “Bradford mentions turkeys, which most likely were served as part of the feast, but no menu such as provided by Willison appears in the primary documents and, although cranberries probably grew in the nearby wetlands, nothing suggests they were harvested. Further, since the settlement had no ovens, butter, or wheat for crusts, there were no pies, pumpkin or otherwise. The most glaring misrepresentation of the First Thanksgiving story, however, which routinely adheres to the above passage from Willison, is that the Native Americans of the Wampanoag were invited to the feast; neither of the primary documents suggests this in any way.”

In addressing this quandary, Epicurious interviewed Kathleen Curtin the food historian at Plimoth Plantation (Plimoth Patuxet), who shares that “Most of today’s classic Thanksgiving dishes weren’t served in 1621,” says Curtin. “These traditional holiday dishes became part of the menu after 1700. When you’re trying to figure out just what was served, you need to do some educated guesswork. Ironically, it’s far easier to discern what wasn’t on the menu during those three days of feasting than what was!”

She elaborates further, “Potatoes—white or sweet—would not have been featured on the 1621 table, and neither would sweet corn. Bread-based stuffing was also not made, though the Pilgrims may have used herbs or nuts to stuff birds. Instead, the table was loaded with native fruits like plums, melons, grapes, and cranberries, plus local vegetables such as leeks, wild onions, beans, Jerusalem artichokes, and squash. (English crops such as turnips, cabbage, parsnips, onions, carrots, parsley, sage, rosemary, and thyme might have also been on hand.) And for the starring dishes, there were undoubtedly native birds and game… Fish and shellfish were also likely [served].

“While modern Thanksgiving meals involve a lot of planning and work, at least we have efficient ovens and kitchen utensils to make our lives easier. Curtin says the Pilgrims probably roasted and boiled their food. ‘Pieces of venison and whole wildfowl were placed on spits and roasted before glowing coals, while other cooking took place in the household hearth,’ she notes, and speculates that large brass pots for cooking corn, meat pottages (stews), or simple boiled vegetables were in constant use.” (4)

“To make victuals both more plentiful and comfortable”

“The Pilgrims had to sell their butter in 1620 to pay expensive port fees caused by delays with the Speedwell. Little did they know that they would not taste cows’ milk, butter, or cheese for another four years. On September 8, 1623, Gov. William Bradford and Dep. Governor Isaac Allerton wrote to the Merchant Adventures in London imploring them to send goats and cattle in order ‘to make victuals both more plentiful and comfortable’ and stating that “the Colony will never be in good estate till they have some.

The London investors agreed, and finally sent over one bull and three heifers in 1623 on the Anne and five more cows on the Jacob in 1624. From that time forward, the food shortages came to an end. Why would the addition of cattle make such a difference?

(Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art).

“As the Pilgrims knew, the addition of milk, cheese and butter was so important to the diet of English colonists that it was called ‘white meat.’ The concentrated calories, proteins, calcium and fats were life sustaining, and particularly important for growing children. Most of the Pilgrims came from yeoman farming backgrounds and knew how to effectively use dairy cows. Dairying was ‘women’s work’ and it was hard and labor-intensive. The Colony women would have worked from dawn to dusk taking care of their cattle.

By 1627, the colonists had sufficient cattle to actually divide them by family group among the 156 colonists. The 1627 Division of Cattle into 13 family groups acts as an invaluable census for all those living in Plymouth during that year. The growth in cattle also caused a demand for farms, which led to the settlement of Kingston, Duxbury, Marshfield, and other towns throughout the colony.” (Mayflower Society Newsletter) (5)

Adopted — A Day of For Thanksgiving

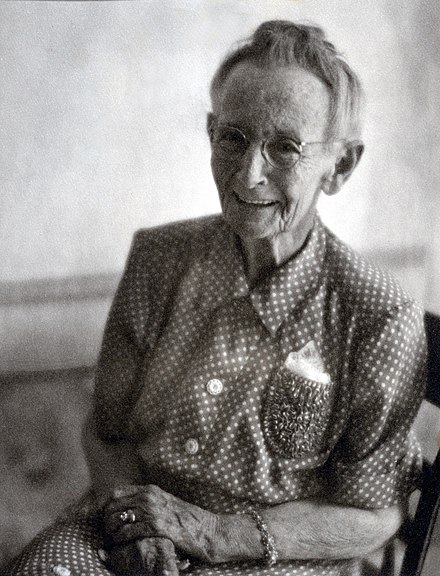

Due to the advocacy of one woman, and a President who listened to her, we eventually gained a national holiday in November.

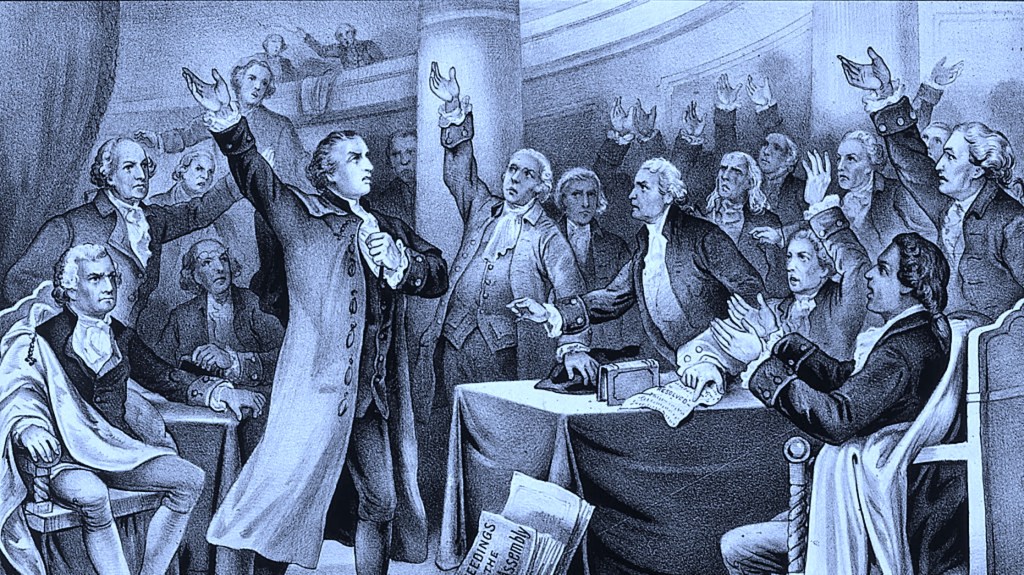

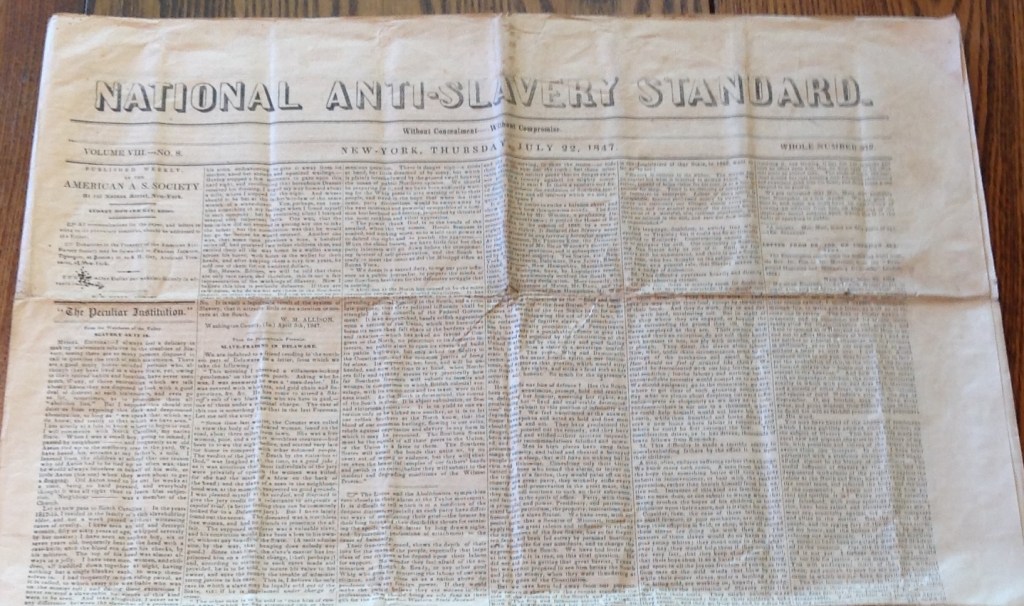

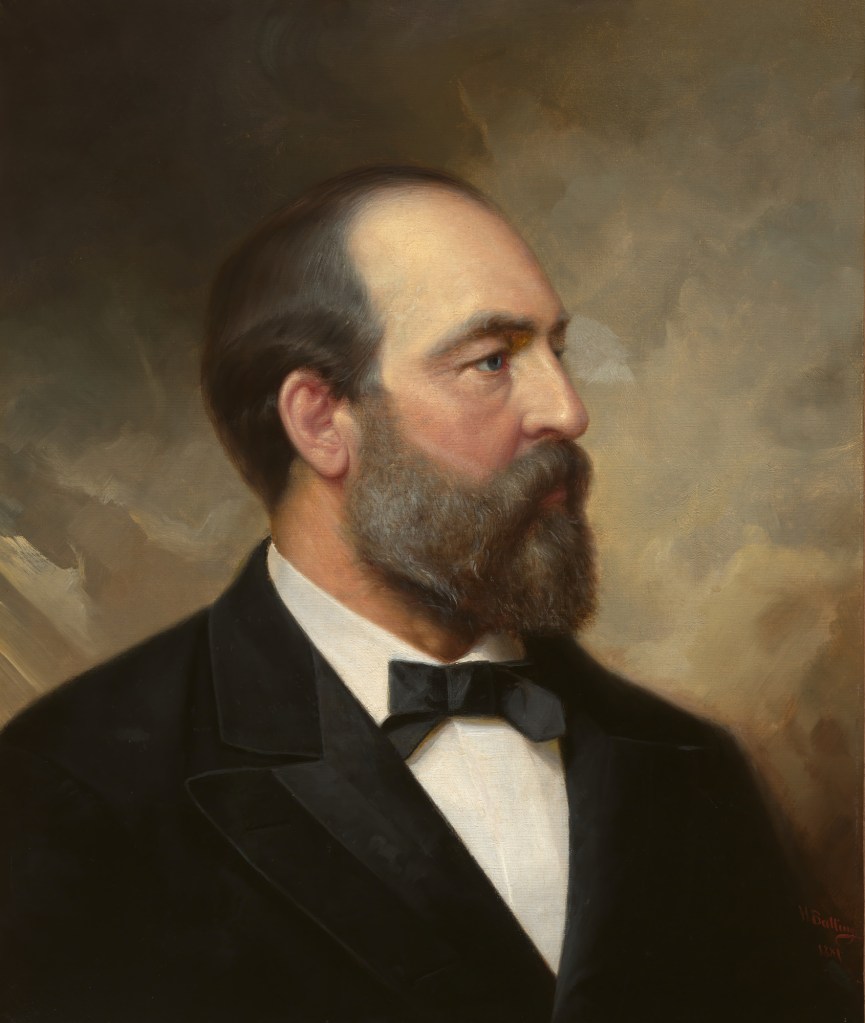

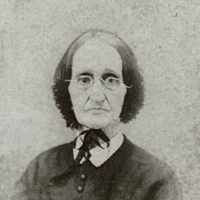

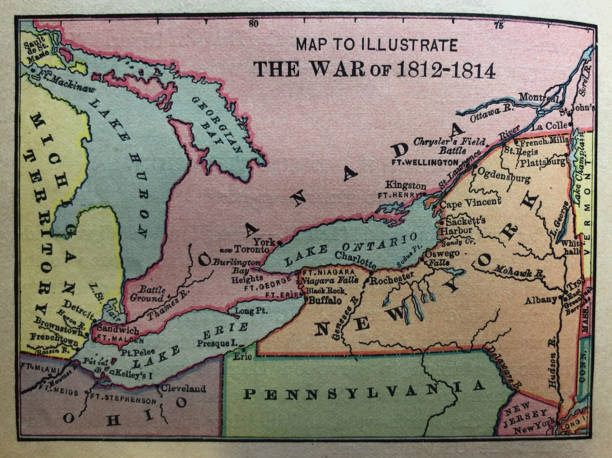

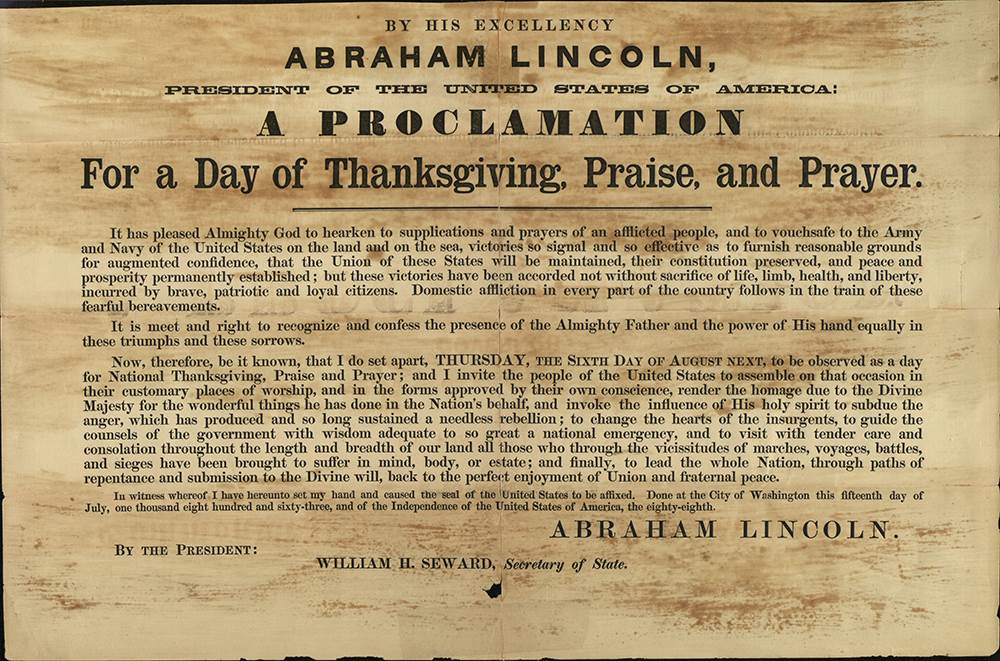

“Sarah Josepha Hale (1788-1879), the writer and editor of the popular periodical Godey’s Lady’s Book, campaigned for the national observance of Thanksgiving Day beginning in 1846. She wrote to each sitting president advocating the adoption of the holiday, but it was only acted upon in 1863 by President Abraham Lincoln (served 1861-1865) during the American Civil War as a means of encouraging national unity.

Sidebar: Sarah Joseph Hale was quite intriguing as she was an early advocate for equal educational opportunities for women. She was the author of the nursery rhyme “Mary Had a Little Lamb” and retired in 1877 at the age of 89. That same year, Thomas Edison spoke the opening lines of Mary’s Lamb as the first speech ever recorded on his newly invented phonograph. Here is a 17 second audio clip (just below his photo), where Edison recalls the original event. Unfortunately, the original recording was too fragile and has not survived.

Americans already celebrated the holiday at different times in different places, but Hale wanted a specific national day of giving thanks to God for the blessings received during the past year. The Civil War context made such a day even more necessary, as both sides occasionally proclaimed days of thanksgiving to recognize and potentially foster divine support for their respective causes.” (World History Encyclopedia, WHE)

“Lincoln proved receptive to Hale’s ideas and officially declared the last Thursday in November ‘as a day of Thanksgiving and Praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the Heavens.’ He added (in an October 3, 1863, proclamation written by Secretary of State William H. Seward) that Americans should ‘with humble penitence for our national perverseness and disobedience, commend to His tender care all those who have become widows, orphans, mourners or sufferers in the lamentable civil strife in which we are unavoidably engaged, and fervently implore the interposition of the Almighty Hand to heal the wounds of the nation and to restore it as soon as may be consistent with the Divine purposes to the full enjoyment of peace, harmony, tranquility and Union.’” (Lincoln Presidential Library)

during the Civil War, circa 1863. (Image courtesy of the Lincoln Presidential Library).

“The modern celebration of the holiday was formalized across the United States only as recently as 1963 under President John F. Kennedy (served 1961-1963), although it had been observed regionally for 100 years prior.” (WHE)

Finally, author Kathleen Donegan writes in Seasons of Misery: Catastrophe and Colonial Settlement in Early America, about the Pilgrims and the Native Peoples at the first celebration in 1621 —

“We love the story of Thanksgiving because it’s about alliance and abundance,” Donegan says… ‘But part of the reason that they were grateful was that they had been in such misery; that they had lost so many people — on both sides. So, in some way, that day of thanksgiving is also coming out of mourning; it’s also coming out of grief. It’s a very interesting narrative for a superpower nation. There is something sacred about humble beginnings. A country that has grown so rapidly, so violently, so prodigiously, needs a story of small, humble beginnings.’” (6)

Finally, Thanksgiving Dinner is Just Not Complete Without Pumpkin Pie!

Every year without fail we gathered together for our annual Thanksgiving dinner. Sometimes we would have twenty people gathered around the table at our home. It would always start out very well mannered and civilized, and then evolve into loosened belts, catching up on goings-on, mountains of dishes, and people yelling at the inevitable football games playing on the afternoon television.

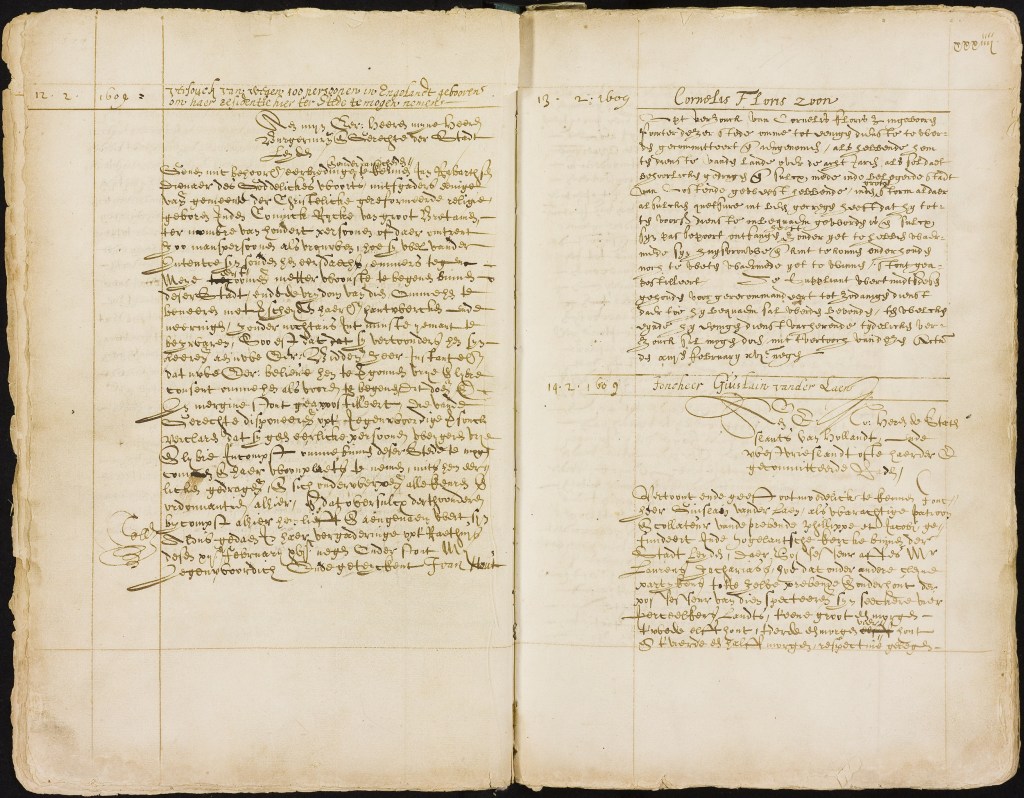

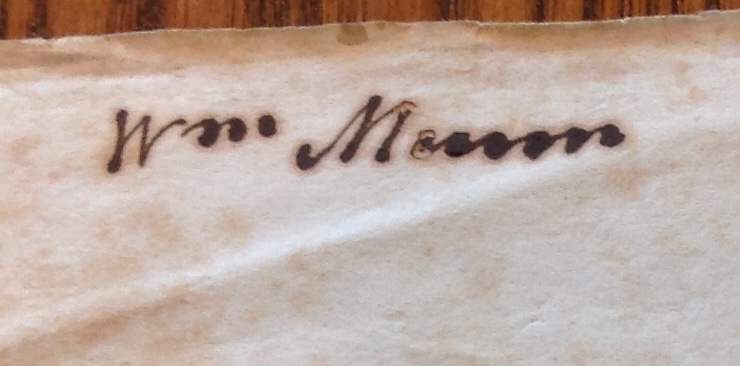

Our mother was a good cook. Later in her life, we convinced her to write out some of her recipes and now we’re glad we did, except for the fact that she had very difficult handwriting to read. (Her excuse was always that when she was younger, she learned shorthand at secretarial school and it had ruined her handwriting. We would not disagree). In any case, for those of you who are interested — her actual recipe as she wrote it out, is transcribed in the footnotes. (7) By the way, the picture of the pie is not Mom’s, it’s from an experiment in pie making by two of her children!

Following are the footnotes for the Primary Source Materials,

Notes, and Observations

Freedom From Want

(1) — four records

The Saturday Evening Post

Thanksgiving

https://www.saturdayeveningpost.com/collections/thanksgiving/

Note: For the text, and Norman Rockwell’s painting, Freedom From Want, 1943.

If It’s Hip, It’s Here

The 37 Best Parodies of Rockwell’s Freedom From Want (aka Thanksgiving Dinner)

https://www.ifitshipitshere.com/37-best-parodies-rockwells-freedom-want-aka-thanksgiving-dinner/

Notes: Freedom From Want — Peanuts version by Charles Schultz, Lego Version by Greg 50 on Flickr, Muppets version by Jim Henson

IESE Business School, University of Navarra

The Power of Myth, by Joseph Campbell

Review of this book by Brian Liggett

https://blog.iese.edu/leggett/2012/02/27/the-power-of-myth-by-joseph-campbell/

Note: For the text.

(NEFTA)

The National Endowment For The Humanities

Who Were the Pilgrims Who Celebrated the First Thanksgiving?

by Craig Lambert

https://www.neh.gov/humanities/2015/novemberdecember/feature/who-were-the-pilgrims-who-celebrated-the-first-thanksgiving

Note: For the text.

What Happened In That First Winter

(2) — seven records

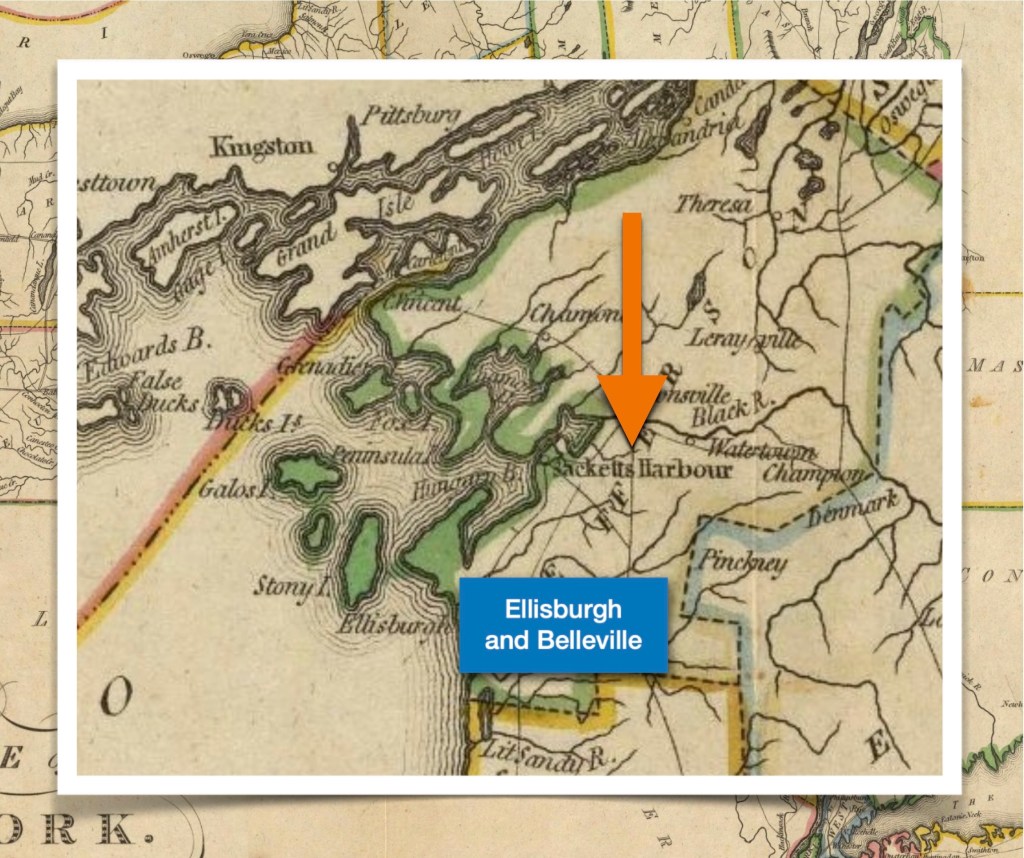

The First Winter of the Pilgrims in Massachusetts, 1620. Colored engraving, circa 19th century. (Image courtesy of The Granger Collection).

Note: As found here, Exploration and the Early Settlers from Of Plymouth Plantation, on page 106:

https://www.muhlsdk12.org/site/handlers/filedownload.ashx?moduleinstanceid=4199&dataid=8729&FileName=Of%20Plymouth%20Plantation.pdf

Note: For the winter artwork.

PBS Learning Media

The First Winter | The Pilgrims

https://www.pbslearningmedia.org/resource/americanexperience27p-soc-firstwinter/the-first-winter-the-pilgrims/

Note: For the text.

(NYNJPA)

The Pilgrims Barely Survived Their First Winter At Plymouth

https://nynjpaweather.com/public/2023/11/17/the-pilgrims-barely-survived-their-first-winter-at-plymouth/

Note: For the text.

Plimoth Pautexet Museums

Who Were The Pilgrims?

Arrival at Plymouth

https://plimoth.org/for-students/homework-help/who-were-the-pilgrims

Note: For the text.

Pilgrim Hall Museum

Charts About The Mayflower Passengers

https://www.pilgrimhall.org/ce_our_collection.htm

Note: We adapted these graphics for this chapter.

The Plymouth Colony Archive Project

Mayflower Passenger Deaths, 1620-1621

Patricia Scott Deetz and James Deetz

http://www.histarch.illinois.edu/plymouth/maydeaths.html

Note: For the text.

The Mayflower Society

Women of The Mayflower

https://themayflowersociety.org/history/women-of-the-mayflower/

Note: For the text.

To Celebrate With A Harvest Feast

(3) — seven records

(NEFTH)

The National Endowment For The Humanities

Who Were the Pilgrims Who Celebrated the First Thanksgiving?https://www.neh.gov/humanities/2015/novemberdecember/feature/who-were-the-pilgrims-who-celebrated-the-first-thanksgiving

Note: For the text.

(VTHMB)

Voyaging Through History, the Mayflower and Britain

Mourt’s Relation (1622)

https://voyagingthroughhistory.exeter.ac.uk/2020/08/25/mourts-relation-1622/

Note: For the cover image.

State Library of Massachusetts

Bradford’s “Of Plimoth Plantation”

https://www.mass.gov/info-details/bradfords-manuscript-of-plimoth-plantation

Note: For the photograph of the original 17th century volume (book) Of Plimoth Plantation.

Saints and Strangers: Being the Lives of the Pilgrim Fathers & Their Families

by George F. Willison

https://archive.org/details/dli.ernet.13804/page/509/mode/2up

Note: For the cover image.

(WHE)

World History Encyclopedia

Thanksgiving Day: A Brief History

by Joshua J. Mark

https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1646/thanksgiving-day-a-brief-history/

Note: For the text.

“Visit of Samoset to the Colony”

Illustration from the 1876 textbook, A Popular History of the United States

by William Cullen Bryant, circa 1876

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:A_popular_history_of_the_United_States_-_from_the_first_discovery_of_the_western_hemisphere_by_the_Northmen,_to_the_end_of_the_first_century_of_the_union_of_the_states;_preceded_by_a_sketch_of_the_(14597125217).jpg

Book page: 400, Digital page: 472/682

Note: For the Samoset illustration.

North Wind Picture Archives

Gift of Meat from Native Americans to Plymouth Colonists

https://www.northwindprints.com/american-history/gift-meat-native-americans-plymouth-colonists-5877641.html

Note: Fir the hand-colored woodcut of a 19th-century illustration.

What Was Really On The Menu?

(4) — three records

Fine Art America

The First Thanksgiving In 1621

by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris

https://fineartamerica.com/featured/the-first-thanksgiving-in-1621-by-ferris-artist-jean-leon-gerome-ferris.html

Note: For the painting.

The Real Story of The First Thanksgiving

by Joanne Camas

https://www.epicurious.com/holidays-events/the-real-story-of-the-first-thanksgiving-menu-recipes-article

Note: For the text and historical insights.

Fine Art Storehouse

First Thanksgiving

https://www.fineartstorehouse.com/photographers/frederic-lewis/first-thanksgiving-11428168.html

Note: A depiction of early settlers of the Plymouth Colony sharing a harvest Thanksgiving meal with members of the local Wampanoag tribe at the Plymouth Plantation, Plymouth, Massachusetts, 1621.

“To make victuals both more plentiful and comfortable”

(5) — two records

Mayflower Society Newsletter, July 2024

by Lisa H. Pennington, Governor General

Note 1: For the text cited in the article — 2024: The 400th Anniversary of the “Great Black Cow” (Access to this actual article is only available through a membership with the Mayflower Society).

Note 2: We have transcribed the relevant newsletter text below:

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Young Herdsmen with Cows

by Aelbert Cuyp, circa 1655-1660

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436064

Note: For the painting image.

Adopted — A Day of For Thanksgiving

(6) — eight records

(WHE)

World History Encyclopedia

Thanksgiving Day: A Brief History

by Joshua J. Mark

https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1646/thanksgiving-day-a-brief-history/

Note: For the text.

Godey’s Lady’s Book

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Godey’s_Lady’s_Book

Note: For the cover image.

Sarah Josepha Hale

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sarah_Josepha_Hale

Note: For the text, and her portrait.

The audio file housed at —

The Internet Archive

Mary had a little lamb

by Thomas Edison

https://archive.org/details/EDIS-SCD-02

Note: For the audio clip reference only.

The Public Domain Review

Edison reading Mary Had a Little Lamb (1927)

https://publicdomainreview.org/collection/edison-reading-mary-had-a-little-lamb-1927/

Note: For the photograph of Thomas Edison, and the MP3 download link at the articles end for the actual audio file used in this chapter.

Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum

Lincoln and Thanksgiving

https://presidentlincoln.illinois.gov/Blog/Posts/169/Abraham-Lincoln/2022/11/Lincoln-and-Thanksgiving/blog-post/

Note: For the text and 1863 proclamation image.

(NEFTA)

The National Endowment For The Humanities

Who Were the Pilgrims Who Celebrated the First Thanksgiving?

by Craig Lambert

https://www.neh.gov/humanities/2015/novemberdecember/feature/who-were-the-pilgrims-who-celebrated-the-first-thanksgiving

Note: For the text.

Finally, Thanksgiving Dinner is Just Not Complete Without Pumpkin Pie!

(7) — one record

All records are family photographs, or ephemera. Below is a transcription of Marguerite’s Pumpkin Pie recipe exactly as she wrote it out —