This is Chapter Three of seven. It’s important to understand that this era was filled with much conflict. The new British America in which the Soule family lived, was exceedingly different from their European experience.

In this chapter, we are starting to explore the life experiences of the Second Generation in America. Like all generations, the one that follows sometimes does things a bit differently than their parents did…

“In my extreme old age and weakness been tender…”

Mary (Becket/Buckett) Soule died circa December 1676. She is buried in the Miles Standish Burial Ground, Duxbury, Plymouth County, Massachusetts. We know her death date because — her son John Soule indicated this in his account of “the inventory of the goods of George Soule, circa 1679, that ‘since my mother died which was three yeer the Last December except some smale time my sister Patience Dressed his victualls’.” (Pilgrim Hall Museum)

George Soule died shortly before 22 January 1679, when inventory was taken of his estate. He is also buried at Myles Standish Burial Ground in Duxbury, Plymouth County, Massachusetts.

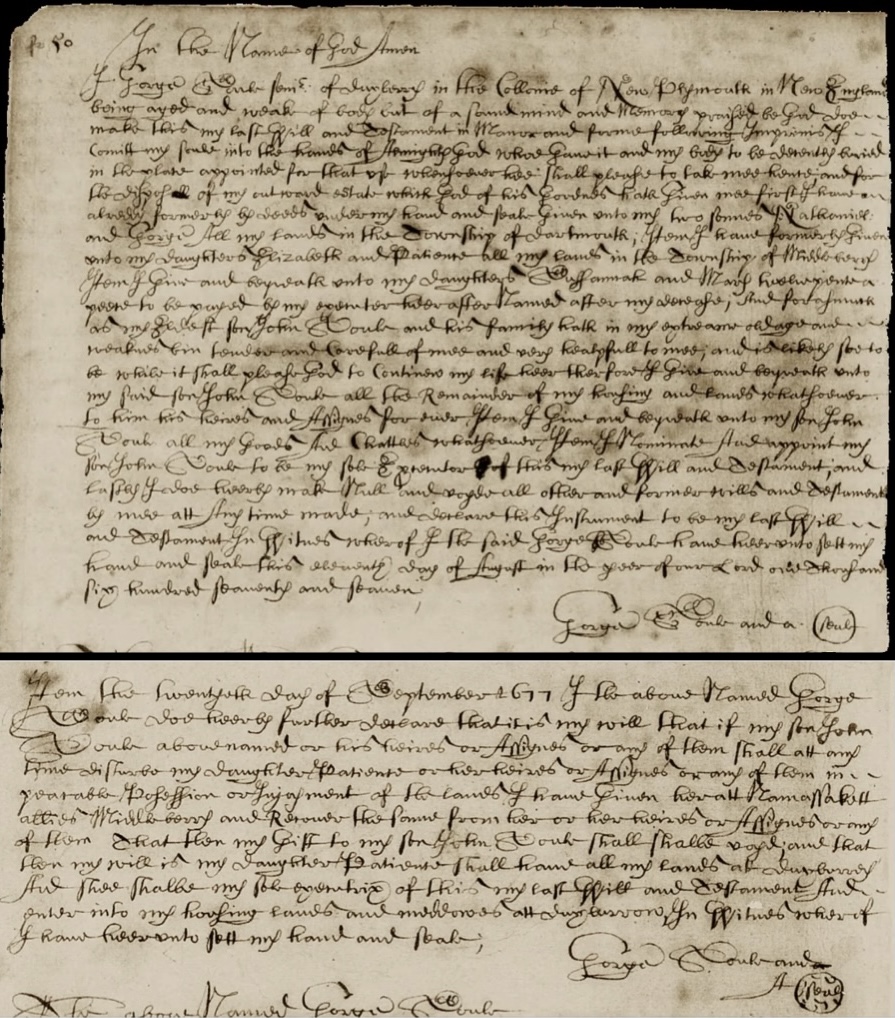

“George Soule [had] made his will on 11 August 1677 and mentions his eldest son John ‘my eldest son John Soule and his family hath in my extreme old age and weakness been tender and careful of me and very helpful to me’. John was his executor and to whom was given nearly all of Soule’s estate.

But after he wrote his will, on 12 September 1677 George seemed to have second thoughts and made a codicil to the will to the effect that if John or any family member were to trouble his daughter Patience or her heirs, the Will would be void. And if such happened, Patience would then become the executor of his last Will and Testament with virtually all that he owned becoming hers. To put his youngest daughter to inherit his estate ahead of his eldest son would have been a major humiliation for John Soule. But John must have done well in his father’s eyes since after his father’s death, he did inherit the Duxbury estate. Twenty years later Patience and her husband sold the Middleboro estate they had received from her father.” (Wikipedia)

We observed that in the inventory list of his estate, there was this notation —“Item bookes” — which reinforces the observation that George Soule was a literate, educated man who read. Most people in the Plymouth Colony did not own books, unless it was a Bible. We wish we knew what the titles of these books were, but we will never know and can only dream of what their pages revealed to this 8x Great-Grandfather.

George Soule, with his long life, had outlived all of his associates who were involved in William Brewster’s Subterfuge, even King James I.

Here is the codicil of September 12, 1677 —

If my son John Soule above-named or his heirs or assigns or any of them shall at any time disturb my daughter Patience or her heirs or assigns or any of them in peaceable possession or enjoyment of the lands I have given her at Nemasket alias Middleboro and recover the same from her or her heirs or assigns or any of them; that then my gift to my son John Soule shall be void; and that then my will is my daughter Patience shall have all my lands at Duxbury and she shall be my sole executrix of this my last will and testament and enter into my housing lands and meadows at Duxbury. (1)

Kids These Days!

We speculate that there isn’t a parent alive today (and also in the past for that matter), who hasn’t rolled their eyes and thought to themselves with a touch of exasperation, kids these days! George and Mary Soule were likely no exception.

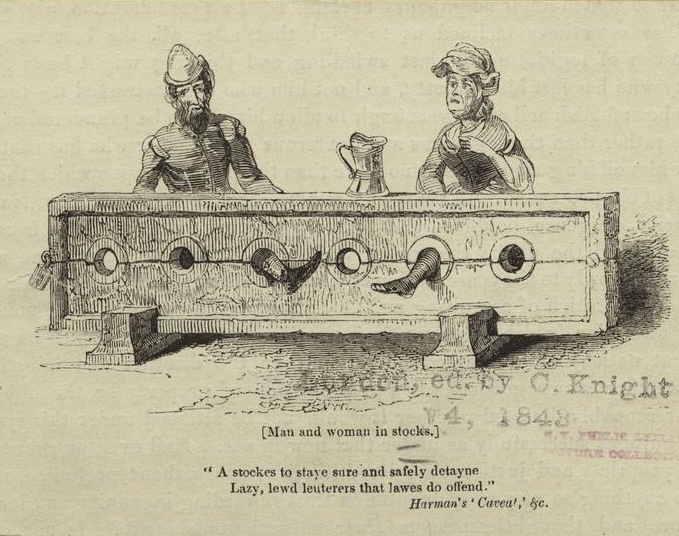

Nathaniel

“Nathaniel may have caused the most colony trouble of any of his siblings. On 5 March 1667/8, he made an appearance in Plymouth court to ‘answer for his abusing of Mr. John Holmes, teacher of the church of Christ at Duxbury, by many false, scandalous and opprobrious speeches’. He was sentenced to make a public apology for his actions, find sureties* for future good behavior and to sit in the stocks, with the stock sentence remitted [because the man he offended asked for mercy to be shown]. His father George and brother John had to pay surety for Nathaniel’s good behavior with he being bound for monies and to pay a fine.

*The Cambridge Dictionary defines surety as “a person who accepts legal responsibility for another person’s debt or behaviour.”

Three years later, on 5 June 1671, he was fined for “telling several lies which tended greatly to the hurt of the Colony in reference to some particulars about the Indians.” And then on 1 March 1674/5 he was sentenced to be whipped for “lying with an Indian woman,” and had to pay a fine in the form of bushels of corn to the Indian woman towards the keeping of her child.”(Wikipedia)

“His crime would have been punished (by the lesser punishment of a fine) if he had committed it with an English woman, but there is other evidence to suggest that sex with Native Americans caused particular anxiety (hence the whipping), as it breached the racial boundaries of the Bible commonwealth itself.) (Whittock)

and just done their time together? Perhaps it would have been easier on George and Mary.

(Image courtesy of the New York Public Library).

Elizabeth

“Elizabeth, like her brother Nathaniel, also had her share of problems with the Plymouth Court. On 3 March 1662/3, the Court fined Elizabeth and Nathaniel Church for committing fornication. Elizabeth then in turn sued Nathaniel Church “for committing an act of fornication with her… and then denying to marry her.” The jury awarded her damages plus court costs.

On 2 July 1667 Elizabeth was sentenced to be whipped at the post “for committing fornication the second time.” And although the man with whom she committed the act was not named, Elizabeth did marry Francis Walker within the following year.” Whittock writes, “These activities do not imply promiscuity on Elizabeth’s part, since many in her society considered intention to marry as allowing licit intercourse. Consequently, about 20 percent of English brides at the time were pregnant at marriage.” (Two sources, see footnotes).

Observations: OK, it’s 400 years later and we’re a bit late to the party. Although we don’t excuse his behavior, perhaps Nathaniel Soule was just both a mouthy cad and a foolish, horny young man? It seems to us however, that Elizabeth was judged a bit unfairly, and likely because she was a woman. Nathaniel Church probably led her on… that seems quite plausible since the court awarded her a judgement. Can you imagine the utter audacity it took for her to sue him in court? And as far as the second case goes, it was likely that her partner was her future husband Francis. But, who knows? Why was this man not named, and why was Elizabeth the only one who was publicly punished?

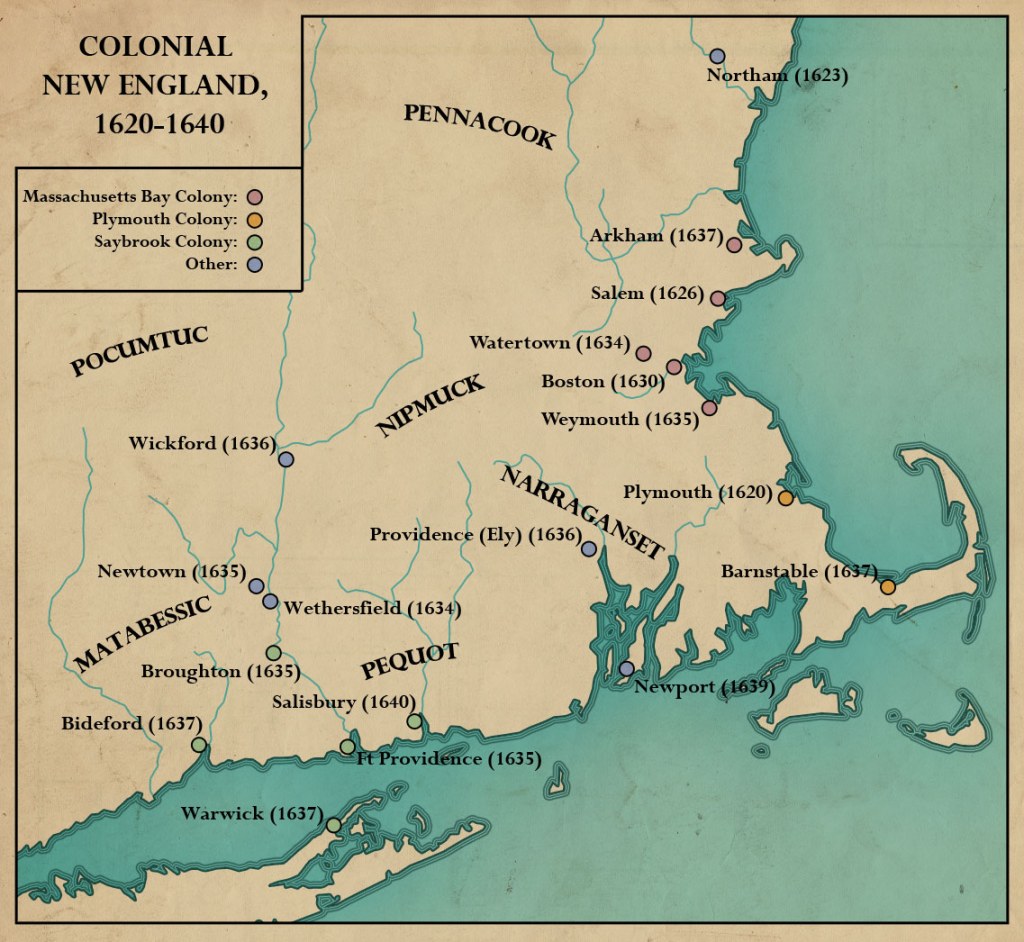

Around the time when Nathaniel Soule was born, the New England area was engaged in a war with some of the native tribes, namely The Pequots. The various wars with the Native Peoples came and went as the populations within the region shifted. Many of these conflicts played out during the lifetimes of George and Mary Soule’s children—we are going to write about the two major conflicts which directly affected this family. (2)

The Pequot War

“The Pequot War was fought in 1636–37 by the Pequot people against a coalition of English settlers from the Massachusetts Bay, Connecticut, and Saybrook colonies and their Native American allies (including the Narragansett and Mohegan) that eliminated the Pequot as an impediment to English colonization of southern New England. It was an especially brutal war and the first sustained conflict between Native Americans and Europeans in northeastern North America.

To best understand the Pequot War, one needs to consider the economic, political, and cultural changes brought about by the arrival of the Dutch on Long Island and in the Connecticut River valley at the beginning of the 17th century and of English traders and settlers in the early 1630s. The world into which they entered was dominated by the Pequot, who had subjugated dozens of other tribes throughout the area during the 1620s and early ’30s in an attempt to control the region’s fur and wampum trade. Through the use of diplomacy, coercion, intermarriage, and warfare, by 1635 the Pequot had exerted their economic, political, and military control over the whole of modern-day Connecticut and eastern Long Island and, in the process, established a confederacy of dozens of tribes in the region.

The struggle for control of the fur and wampum trade [decorative strings of beads] in the Connecticut River valley was at the root of the Pequot War. Before the arrival of the English in the early 1630s, the Dutch and Pequot controlled all the region’s trade, but the situation was precarious because of the resentment held by the subservient Native American tribes for their Pequot overlords.

Map of Colonial New England, 1620-40, by Ed Thomasten.

(Image courtesy of Deviantart.com).

The war lasted 11 months and involved thousands of combatants who fought several battles over an area encompassing thousands of square miles. In the first six months of the war, the Pequot, with no firearms, won every engagement against the English. Both sides showed a high degree of sophistication, planning, and ingenuity in adjusting to conditions and enemy countermeasures.

The turning point in the conflict came when the Connecticut colony declared war on the Pequot on May 1, 1637, following a Pequot attack on the English settlement at Wethersfield—the first time women and children were killed during the war. Capt. John Mason of Windsor was ordered to conduct an offensive war against the Pequot in retaliation for the Wethersfield raid.

The most-significant battles of the war then followed, including the Mistick Campaign of May 10–26, 1637 (Battle of Mistick Fort, present day Mystic), during which an expeditionary force of 77 Connecticut soldiers and as many as 250 Native American allies attacked and burned the fortified Pequot village at Mistick. Some 400 Pequot (including an estimated 175 women and children) were killed in less than an hour, half of whom burned to death.

The Battles of Mistick Fort and the English Withdrawal were significant victories for the English, and they led to their complete victory over the Pequot six weeks later at the Swamp Fight in Fairfield, Connecticut—the last battle of the war.” (Encyclopædia Britannica) (3)

King Philip’s War

Our Soule ancestors were used to thinking about kings and queens of the European sort, but now they were going to meet a local king, who was new to their understanding. The following is excerpted from the Native Heritage Project article, King Philip’s War:

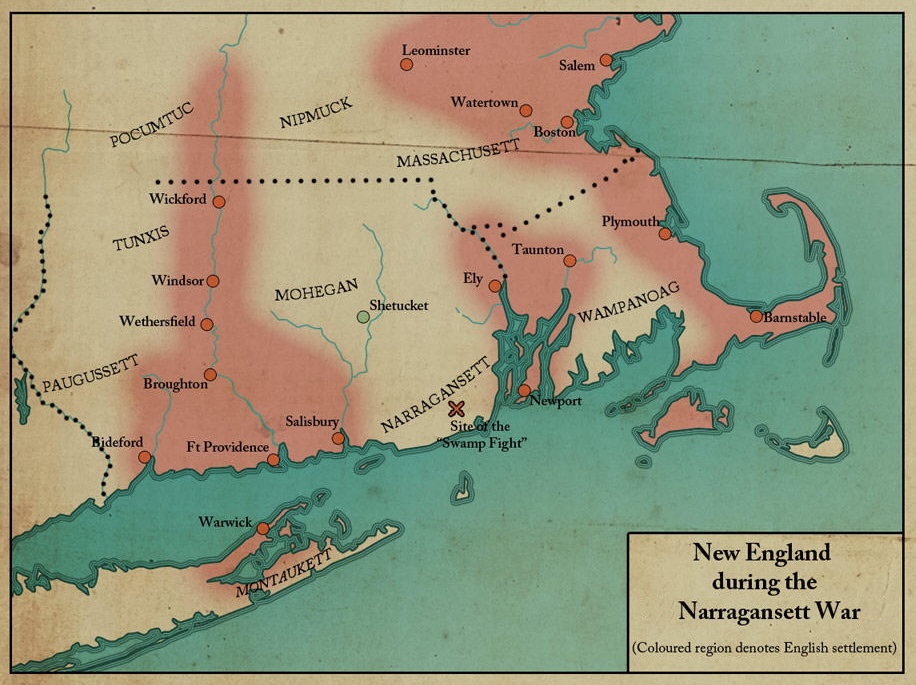

“King Philip’s War was sometimes called the First Indian War, Metacom’s War, or Metacom’s Rebellion and was an armed conflict between Native American inhabitants of present-day southern New England, English colonists and their Native American allies in 1675–76. The war is named after the main leader of the Native American side, Metacomet, known to the English as ‘King Philip’s War.”

“Throughout the Northeast, the Native Americans had suffered severe population losses due to pandemics of smallpox, spotted fever, typhoid and measles, infectious diseases carried by European fishermen, starting in about 1618, two years before the first colony at Plymouth had been settled. Plymouth, Massachusetts, [which] was established in 1620 with significant early help from Native Americans, particularly… Metacomet’s father and chief of the Wampanoag tribe.”

“Prior to King Philip’s War, tensions fluctuated between different groups of Native Americans and the colonists, but relations were generally peaceful. As the colonists’ small population of a few thousand grew larger over time and the number of their towns increased, the Wampanoag, Nipmuck, Narragansett, Mohegan, Pequot, and other small tribes were each treated individually (many were traditional enemies of each other) by the English colonial officials of Rhode Island, Plymouth, Massachusetts Bay, Connecticut and the New Haven colony.”

Over time, “…the building of [Colonial] towns… progressively encroached on traditional Native American territories. As their population increased, the New Englanders continued to expand their settlements along the region’s coastal plain and up the Connecticut River valley. By 1675 they had even established a few small towns in the interior between Boston and the Connecticut River settlements. Tensions escalated and the war itself actually started almost accidentally, certainly not intentionally, but before long, it has spiraled into a full scale war between the 80,000 English settlers and the 10,000 or so Indians.”

From Wikipedia: “The war was the greatest calamity in seventeenth-century New England and is considered by many to be the deadliest war in Colonial American history. In the space of little more than a year, 12 of the region’s towns were destroyed and many more were damaged, the economy of Plymouth and Rhode Island Colonies was all but ruined and their population was decimated, losing one-tenth of all men available for military service. More than half of New England’s towns were attacked by Natives.”

King Philip’s War began the development of

The Name of War:

an independent American identity.

The New England colonists faced their enemies without support

from any European government or military,

and this began to give them a group identity separate and distinct from Britain.

King Philip’s War and the Origins of American Identity

by Jill Lepore

Nine Men’s Misery

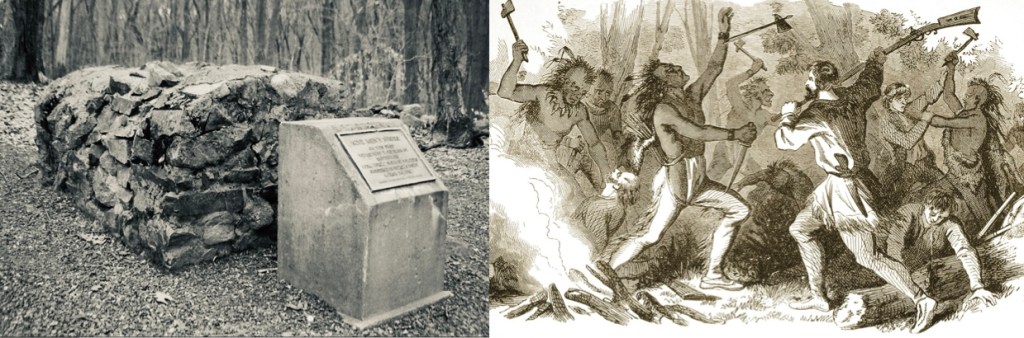

Benjamin Soule, the youngest son of George and Mary Soule, “fell with Captain Pierce 26 March 1676 during King Philip’s War.” (The Great Migration) We observed this notation about and researched a bit further, learning that —

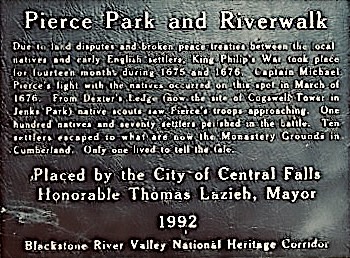

“On March 26, 1676, during King Philip’s War, Captain Michael Pierce led approximately 60 Plymouth Colony militia and 20 Wampanoag warriors in pursuit of the Narragansett tribe, who had burned down several Rhode Island settlements and attacked Plymouth Colony. Pierce’s troops caught up with the Narragansett, Wampanoag, Nashaway, Nipmuck, and Podunk fighters, but were ambushed in what is now Central Falls, Rhode Island.

Pierce’s troops fought the Narragansett warriors for several hours but were surrounded by the larger force. The battle was one of the biggest defeats of colonial troops during King Philip’s War; nearly all of the colonial militia were killed, including Captain Pierce and their Wampanoag allies (exact numbers vary by account). The Narragansett tribe lost only a handful of warriors.

Ten of the colonists were taken prisoner. Nine of these men were tortured to death by the Narragansett warriors at a site in Cumberland, Rhode Island, currently on the Cumberland Monastery and Library property, along with a tenth man who survived. The nine men were buried by English colonists who found the corpses and created a pile of stones [a cairn] to memorialize the men. This pile is believed to be the oldest war memorial in the United States, and a cairn of stones has continuously marked the site since 1676.” (Wikipedia)

To this day, it is unclear if Benjamin Soule is buried near the battle site, which is now known as the Pierce Park and Riverwalk, Central Falls, Providence County, Rhode Island. Or, if perhaps he was one of the soldiers who were tortured and are buried near the cairn mentioned above.

“In terms of population, King Philip’s War was the bloodiest conflict in American history. Fifty-two English towns were attacked, a dozen were destroyed, and more than 2,500 colonists died — perhaps 30% of the English population of New England.” (Westfield)

In the next chapter, we move continue with the specific history of Generation Two in America of the Soule descendants. We will be focusing on George and Mary’s daughter Patience (Soule) Haskell, our 7x Great Grandmother and her husband John. (5)

Following are the footnotes for the Primary Source Materials,

Notes, and Observations

(1) — seven records

“In my extreme old age and weakness been tender…”

Mary Soule

in the U.S., Find a Grave Index, 1600s-Current

https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/89809163:60525

and here:

Mary Beckett Soule

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/26862296/mary-soule?_gl=1*1e3xq4g*_ga*MzEyNDMzMzU1LjE3NDAzMzEyOTI.*_ga_4QT8FMEX30*N2Q1YTE1YTQtN2EwYi00ZjFlLTkzYTAtNzIxYzI5ZWMxN2IzLjEuMC4xNzQwMzMxMjkyLjYwLjAuMA..*_gcl_au*NjE1ODQzOTgzLjE3NDAzMzEyOTI.

Pilgrim Hall Museum

The Last Will and Testament of George Soule

https://www.pilgrimhall.org/pdf/George_Soule_Will_Inventory.pdf

Note: For the text.

George Soule

in the U.S., Find a Grave Index, 1600s-Current

https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/2192512:60525

and here:

George Soule

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/5728447/george-soule

George Soule (Mayflower passenger)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Soule_(Mayflower_passenger)

Note: For the text.

Caleb Johnson’s Mayflower History.com

George Soule

http://mayflowerhistory.com/soule/

Note: For the text regarding his George Soule’s Will codicil.

Kids These Days!

(2) — four records

George Soule (Mayflower passenger)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Soule_(Mayflower_passenger)

Note: For the text.

Cambridge Dictionary

Surety definition

https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/surety#google_vignette

Note: For the text.

Mayflower Lives Pilgrims in a New World and the Early American Experience

by Martyn Whittock

https://myuniuni.oss-cn-beijing.aliyuncs.com/files/sat/Mayflower Lives Pilgrims in a New World and the Early American Experience by Whittock, Martyn (z-lib.org).epub.pdf

Book pages: 242-244

Note 1: .pdf download file from the above link.

Note 2: Chapter 13, “The Rebels’ Story: the Billingtons, the Soules, and Other Challenges to Morality and Order”

Note 3: From the index: Soule, see: 14 The details of the Soules’ offenses and punishments can be found in C. H. Johnson, The Mayflower and Her Passengers, 207–208.

New York Public Library Digital Collections

Man and Woman in Stocks

https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e1-1d93-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Note: For the illustration.

The Pequot War

(3) — four records

Encyclopædia Britannica

Pequot War, United States history [1636–1637]

by Kevin McBride

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Pequot-War

Note: For the text.

Deviantart.com

Colonial New England, 1620-40 (map)

by Ed Thomasten

https://www.deviantart.com/edthomasten/art/New-England-1620-40-245657170

Note: For the map image.

Media Storehouse

Felix Octavius Carr Collection

Puritans Barricading Their House Against Indians

by Albert Bobbett, circa 1877

https://www.mediastorehouse.com/heritage-images/puritans-barricading-house-indians-19044638.html

Note: For the image.

Engraving depicting The Attack on The Pequot Fort at Mystic

from John Underhill Newes from America, London, 1638

by Engraver unknown

File:Mystic Massacre in New England 1638 Photo Facsimile.png

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mystic_Massacre_in_New_England_1638_Photo_Facsimile.png

Note: For the Pequot Fort image.

King Philip’s War

(4) — eight records

Native Heritage Project

King Philip’s War

https://nativeheritageproject.com/2012/09/02/king-philips-war/

King Philip’s War

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/King_Philip’s_War

World History Encyclopedia

Death of King Philip or Metacom

https://www.worldhistory.org/image/13670/death-of-king-philip-or-metacom/

Note: For the illustration.

Britannica.com

King Philip’s War

https://www.britannica.com/event/King-Philips-War

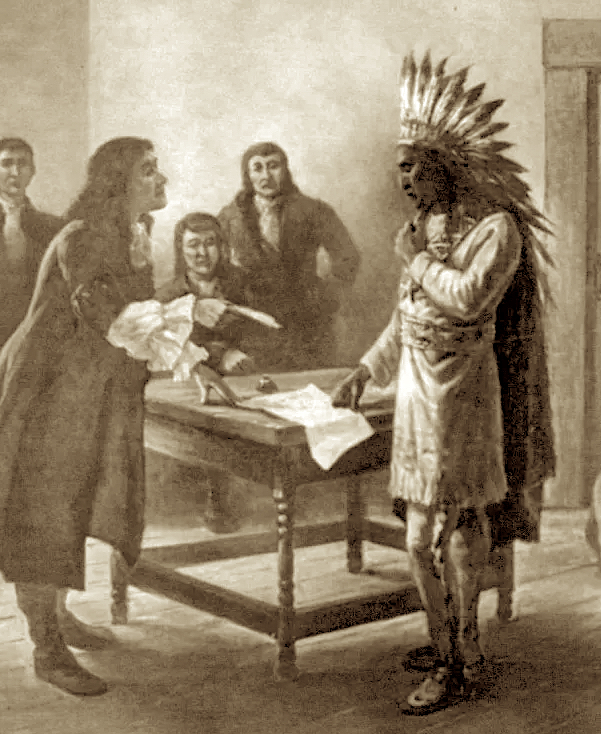

Note: For the illustration, Metacom (King Philip), Wampanoag sachem, meeting settlers, c. 1911

A group of Indians armed with bow-and-arrow, along with a fire in a carriage ablaze, burn a log-cabin in the woods during King Philip’s War, 1675-1676, hand-colored woodcut from the 19th century.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:KingPhilipsWarAttack.webp

Note: For the illustration.

National Geographic | Education

The New England Colonies in 1677

https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/massachusetts-1677/

Note: For the map image.

America’s Best History, Pre-Revolution Timeline – The 1600s

1675 Detail

https://americasbesthistory.com/abhtimeline1675m.html

Note: For the illustration depicting the capture of Mrs. Rolandson during the King Philip’s War between colonists and New England tribes, 1857, Harper’s Monthly.

The Name of War: King Philip’s War and the Origins of American Identity

by Jill Lepore

Vintage Books, 1999

Book pages: 5-7

Note: For the text.

Nine Men’s Misery

(5) — eight records

George Soule in the

New England, The Great Migration and The Great Migration Begins, 1620-1635

https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/2496/records/65782?tid=&pid=&queryId=41c48ad9-6fb5-45be-b3c3-255e8c9d21f4&_phsrc=GMi2&_phstart=successSource

Book pages: 1704-1708 , Digital pages: 393-397/795

Notes: Not all of this information is considered to be correct by today’s historians. Son Benjamin Soule’s death is mentioned on digital page 396/795.

Deviantart.com

The Narragansett War 1645 (map)

by Ed Thomasten

https://www.deviantart.com/edthomasten/art/The-Narragansett-War-1645-332325221

Notes: For the map image. Observe that the map has the incorrect year of 1645, which we have corrected.

Nine Men’s Misery

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nine_Men’s_Misery

Note: For the text.

Atlas Obscura

Nine Mens Misery

https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/nine-mens-misery

Note: For the image.

HMdb.org

The Historical Marker Database

Nine Men’s Misery

https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=2924

Notes: For the text on the plaque.

History Net

King Philip’s War And A Fight Neither Side Wanted

by Douglas L. Gifford

https://www.historynet.com/king-philips-war-and-a-fight-neither-side-wanted/

Note: For the battle illustration.

Benjamin Soule (Veteran)

1651 – 1676 – Pierce Park and Riverwalk

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/278272111/benjamin-soule

Note: For the plaque image.

Westfield State College

Institute for Massachusetts Studies

Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Volume 37, Fall 2009

“Weltering in Their Own Blood”: Puritan Casualties in King Philip’s War

by Robert E. Cray, Jr.

https://www.westfield.ma.edu/historical-journal/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Weltering-in-their-Own-Blood-Puritan-Casualties.pdf

Book pages: 106-123

Note: For the text.