This is Chapter 1 of 3, being the very first of our family line narratives that feature southern Europe and South America. Accordingly, this line will also be our first dual language family history, being written in two formats.

In total, there are 6 chapters: the first set of 3 chapters is written in English, and are labeled as One, Two, Three. The following second set of 3 chapters is translated into Portuguese, and are labeled as Primeira, Segunda, Terceira.

Eis um exemplo: No total, existem 6 capítulos: o primeiro conjunto de 3 capítulos está escrito em inglês e intitula-se Um, Dois e Três. O segundo conjunto de 3 capítulos está traduzido para português e intitula-se como Primeira, Segunda, Terceira.

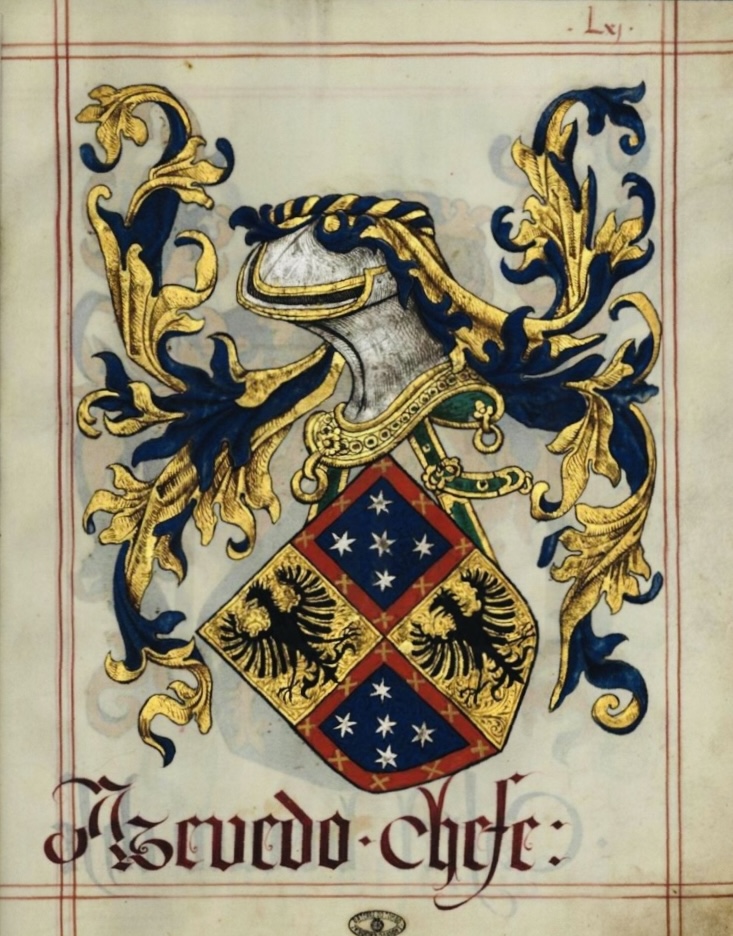

(Family photograph).

Intertwined

When we married in 2008, we had already spent ten years together as a couple. As I sit here and tap the computer keys to write these chapters, I realize that we are coming up on nearly 30 years together as a family. So, what does it mean to have a family like ours? Especially one where, through your research, you discover long generational family histories going back for sometimes hundreds of years?

My husband Leandro is from northeast Bahia, Brazil, and I [Thomas], am from northeast Ohio, USA — and for many years we have lived in various places: California, Ohio, Hawaii, Brazil, and now Portugal.

Our families are interconnected like two ribbons that have intertwined through time to create a strong silken cord that binds us all together. This chapter is about those family lines that originate from Leandro’s side of things; first in Portugal, and then in Brazil. (1)

— Thomas

(Image courtesy of the British Historical Society of Portugal).

The “Battle of Aljubarrota [was] fought between Portugal and Castille near the monastery of Batalha, [and was] called this name due precisely to the battle won by Portugal with the help of English archers with experience from France, in what was to be called the 100 year war”. This victory secured for the Kingdom of Portugal sovereignty against the ambitions of its neighbors.

What Does the Coutinho Family Name Mean in Portugal?

The deeper history of this family has been enlightening. On the paternal side of his family, Leandro’s father Paulo has the classic Portuguese surname of: Coutinho. This name is connected to the de Azervedo(s) (or the spelling variant) the de Azeredo(s). [Note the difference between the interim v, or r letter]. This led us to many interesting discoveries, but before we go there, we first we need to provide some general background information.

“The surname Coutinho is of Portuguese origin, belonging to the toponymic class of surnames, which are derived from the place where the initial bearer once lived or held land. Specifically, Coutinho comes from a diminutive form of couto, which referred to a fenced or enclosed place, such as a hunting preserve or a protected area. Therefore, Coutinho would have originally denoted someone who lived near or was associated with a small enclosed area or preserve.” (Wisdom Library)

Wikipedia also tells us that, “Coutinho is a noble Portuguese language surname. It is from Late Latin cautum, from the past participle of cavere to make safe.” (Wikipedia) (2)

The Marshals of the Kingdom of Portugal

The office of Marshal of the Kingdom of Portugal (Marechal do Reino de Portugal, sometimes Mariscal) was created by King Ferdinand I of Portugal in 1382, in the course of the reorganization of the higher offices of the army of the Kingdom of Portugal. The Marshal was directly subordinate to the Constable of Portugal (Condestável), being principally responsible for the high administrative matters, including the quartering of troops, supplies and other logistical matters.

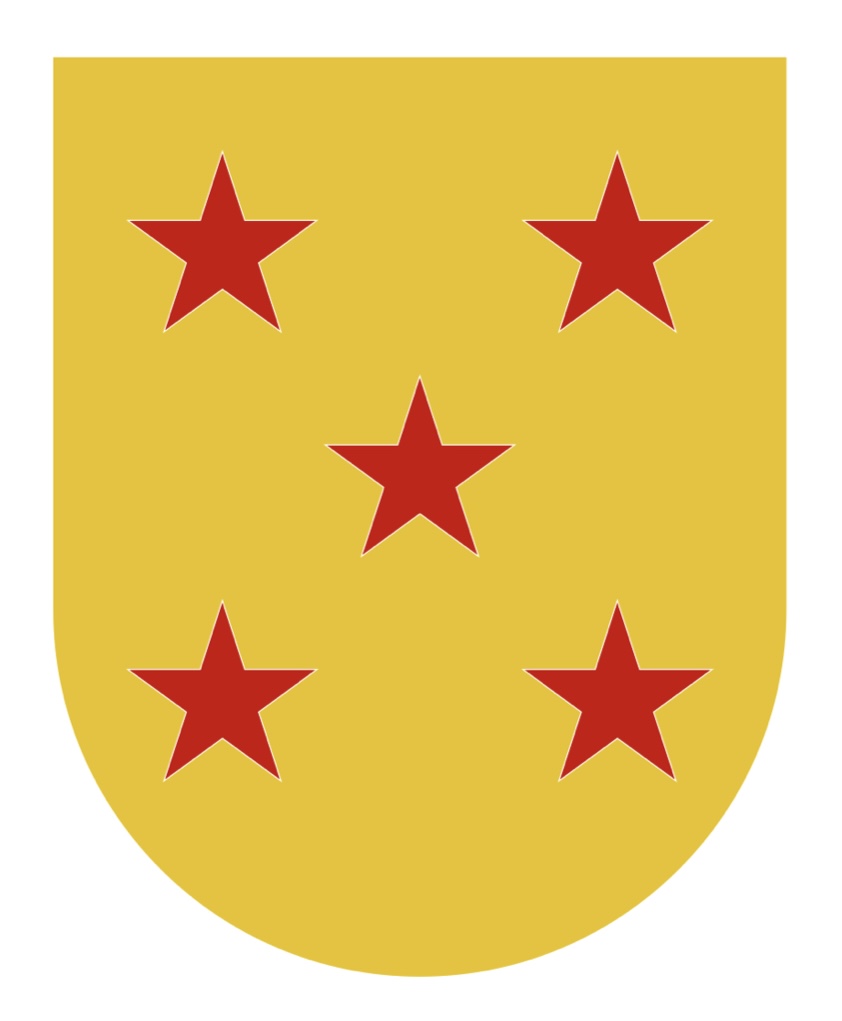

Commander Gonçalo Vasques de Azevedo was appointed the first Marshal of the Kingdom in 1382. This title then became known as The Count(s) of Marialva. The office then passed to his son-in-law, Dom Gonçalo Vasques Fernandes Coutinho — This office was maintained within the Coutinho family until the Iberian Union of 1580.

- Dom Gonçalo Vasques Fernandes Coutinho, the First Count of Marialva, (circa 1385— circa 1450). In 1412, Fernandes Coutinho married Dona Maria de Sousa (died 1472), the natural daughter of Lopo Dias de Sousa, master of the Order of Christ.

- Dom Gonçalo Coutinho, the Second Count of Marialva, (circa 1415 — January 20, 1464). He died in Tangier, Morocco. Gonçalo was married to Beatriz de Melo, daughter of Martim Afonso de Melo and Briolanja de Sousa.

- Dom João Coutinho, the Third Count of Marialva, (circa 1450 — August 24, 1471).

- Dom Francisco Coutinho, the Fourth Count of Marialva, (circa 1480 — February 19, 1543). He married Beatriz de Meneses, 2nd Countess of Loulé.

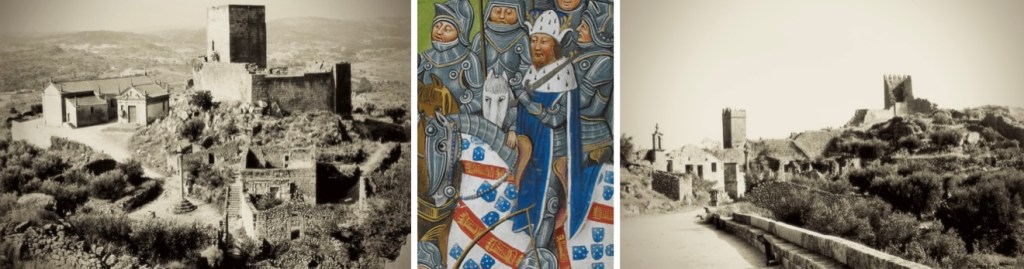

- Dona Guiomar Coutinho, 5th Countess of Marialva, 3rd Countess of Loulé, who married Fernando, Duke of Guarda, (1510 — 1534). He was the son of Manuel I and Maria of Aragon. (The portion of the Castle of Guarda still stands to this day).

by King Afonso V of Portugal in 1440. (See footnotes for all sources).

At first glance, we thought that this contemporary coat-of-arms was just a little bit plain Jane, (in Portuguese, you might say that it needs salt and pepper). Then we came to realize that this is what authenticity looks like.

Research Observation: It is rather astonishing in genealogy research, to come across an instance where you can specifically identify the foundational origin and formalization of a family surname by royal decree, (in this case, circa 1382). Prior to this period most common families did not have true surnames.

*Very nearly all Coutinho-named descendants in Portugal likely related to this man’s family line. Google tells us that this timeframe from then-to-now is about 650 years. (If we allow about 25 years or so between generations, this allows for approximately 26 generations of Coutinho(s). (3)

The Ancient Heraldry of the Coutinho Family

“Heraldry has been practiced in Portugal at least since the 12th century, however it only became standardized and popularized in the 16th century, during the reign of King Manuel I of Portugal, who created the first heraldic ordinances in the country. Like in other Iberian heraldic traditions, the use of quartering and augmentations of honor is highly representative of Portuguese heraldry, but unlike in any other Iberian traditions, the use of heraldic crests is highly popular”.

The Important Significance of the Livro do Armeiro-Mor

“The Livro do Armeiro-Mor is an illuminated manuscript dating back to 1509, [created] during the reign of King Manuel I of Portugal. The codex is an armorial, a collection of heraldic arms, authored by the King of Arms João do Cró. It is considered one of the masterpieces of illuminated manuscripts preserved in Portugal… [It is] the oldest surviving Portuguese armorial to this day, being the oldest source we have regarding certain arms, and also for the beauty of its magnificent illuminations, it is considered the most important Portuguese armorial. It has been called the supreme monument of what we can call Portuguese heraldic culture.

The work… was entrusted to the custody of the Chief Armourer, Álvaro da Costa, appointed in 1511, in whose family the position and the custody of the book remained for more than ten generations. For this reason, the Livro do Armeiro-Mor escaped the great 1755 Lisbon earthquake, which destroyed, among many other things, the Chancellery of Nobility.” (Wikipedia)

One can observe that some representation of Coats-of-Arms feature the escutcheon (shield) tilted at an angle, and the addition of other decorative elements throughout, which make Portuguese armory unique. These elements, however, were added through artistic license by the original artist(s) who crafted the Livro do Armeiro-Mor. Observe also that the stars are not 5-points, but are 7-points. As such, these alterations and additions are not part of the fundamental original coat-of-arms criteria.

What Did the Colors Mean?

The colors in heraldry are called tinctures. Old French words were used to describe the colors of the background, which came to have different meanings. Red (vermelho) was the color of a warrior and nobility, blue (azul) for truth and sincerity, black (negro) for piety and knowledge, and green (verde) for hope and joy. Presently, Portuguese heraldry has seven colors (tinctures) including two metals (gold/ouro, silver/prata) and five colors (blue, red, purple, black, green).

- Estucheon, the shape of the shield. “Since very early, the round bottom shield has been the preferred shape to display the coat-of-arms in Portugal, causing this shape to often be referred as the Portuguese shield”.

- Helm, the top center of this shape, where future generations might add elements to represent their individual family.

- Charge, there is no charge, but only a yellow (ouro) field.

- Ordinaries, In this family, they had 5 stars on a yellow (ouro) field, the designs that appeared on the field. A star with five points and straight sides is called a mullet.

Note: For an interesting history as to why the need for heraldry emerged in English history, see the chapter, The Ancient Bonds of Erth — One, Family Heraldry. That chapter covers symbolic thinking in a pre-literate world, the meaning of various shapes and colors, and what a Coat-of-Arms actually is, versus a Family Crest. The exact same reasons for these developments apply in a parallel manner to the Kingdom of Portugal, even though it was a different country. (https://ourfamilynarratives.com/2022/06/13/the-ancient-bonds-of-erth-one-family-heraldry/)

There are extensive records for the noble classes of Portugal found in the three volume set of books titled, Nobreza de Portugal e Brasilia. These books feature the family names described above, and others.

“The Portuguese nobility was a social class enshrined in the laws of the Kingdom of Portugal with specific privileges, prerogatives, obligations and regulations. The nobility ranked immediately after royalty and was itself subdivided into a number of subcategories which included the titled nobility and nobility of blood at the top and civic nobility at the bottom, encompassing a small, but considerable proportion of Portugal’s citizenry.

The nobility was an open, regulated social class. Accession to it was dependent on a family’s merit, or, more rarely, an individual’s merit and proven loyalty to the Crown over generations. Formal access was granted by the monarch through letters of ennoblement. A family’s status within the noble class was determined by continued and significant services to Crown and country.” (Wikipedia)

The ranks of the titled nobility below The Royals, although similar to those in other European countries, have their idiosyncrasies in Portugal. They are listed here in hierarchical order and are slightly simplified for this family history.

Here are just a few examples of one ranked Noble in each category:

- Dukedoms — The Duke of Viseu, created 1415.

- Marquisates —The Marquis of Pombal, created 1769. Renowned for the rebuilding of Lisbon after the 1755 earthquake, tsunami, and fire which destroyed the city.

- Countships — The Coutinho family as The Counts of Marialva, created 1440.

- Viscountcies — The Viscount of São Jorge, created 1893.

- Baronies — The Baron of Serra da Estrela, created 1818. (4)

(Image courtesy of Lifecooler).

We Are From Two of the 72 Portuguese Noble Class Families

The Coutinho Family later combined through marriage with another family from the same noble class. Known by both surname spellings, either Azerêdo or Azervêdo, this consolidation created the House of Azerêdo – Coutinho. The Coat-of-Arms for each family is featured within the Sintra National Place of Portugal. “…King Manuel I created the Coats-of-Arms Room (Sala dos Brasões) between 1515 – 1518, using the wealth engendered by the exploratory expeditions in the Age of Discovery. The room features a magnificent wooden coffered domed ceiling decorated with 72 coats-of-arms of the King and the main Portuguese noble families.”

for King Manuel I of Portugal.

Throughout this history, we have been focusing on the paternal family line of the Coutinho family. We also have interesting things to share about the maternal side, the Oliveira family…

What Does the Oliveira Family Name Mean in Portugal?

“Oliveira is a Portuguese (and Galician) surname, used in Portuguese-speaking countries, and to a lesser extent in former Portuguese and Spanish colonies. Its origin is from the Latin word olivarĭus , meaning olive tree. Its first documented use dates back to the 13th century, from Évora noble Pedro de Oliveira, and his son, Braga archbishop D. Martinho Pires de Oliveira. Further tracing of its origins show that it derives from ancient Roman aristocrats from the gens* Oliva. (*Individuals who shared the same descent from a common ancestor).

Furthermore, this surname takes us back to Biblical times, where the olive and olive tree were always very important to the Hebrew culture. One of the 12 Hebrew tribes, [known as Asher], had an olive tree inside of the tribe emblem. This is compelling evidence that the Asher Hebrew tribe name could have likely been transliterated into the Portuguese Oliveira surname, to better align with Portuguese Christian society and culture.

In Portuguese, de Oliveira may [therefore] refer to both of the olive tree and from the olive tree. In archaic Portuguese, we find the register of surnames with variations of their spelling, such as Olveira and Ulveira. By the time of King Diniz I, king of Portugal in 1281, Oliveira was already ‘an old, illustrious and honorable family’, as the King’s Books of Inquisitions show.

Comment: I have been pondering about what my mother-in-law Lindaura would have thought about this next part of the history. We do not know how much she truly knew of her family’s history… However, one very specific fact that you could certainly know about her was that she was a very, very devout Roman Catholic. (All her roads led to Rome). This next part was a bit if a revelation to us.

“It is noteworthy to mention that the offspring of the [12 Tribes of Israel] intentionally settled between Galicia [northwest Spain] and Portugal for two reasons — First, because they were inland and far from the great centers of Spain, where the first killings of Judeans (pogroms) began. These pogroms were promoted by fanatical Catholic priests of the Dominican and Carmelite orders, who urged the ignorant Christian population to kill the New Christian Jews and the unconverted Judeans. Second, Galicia and Portugal gave them freedom to cross the borders among the different countries accordingly to the laws of each State”. (Wikitree) This lead to the population being labeled historically with the ethnic definition of Sephardic Jews.

Research observation: We know that this family surname is very old in Portugal, however, we don’t yet know when it connects with the line from which our family descends. We could be from the very old branch, or the branch of people who adopted this surname during the times of oppression, or both.

Sephardic Jews

Oliveira, de Oliveira, and d’Oliveira, have historically been used by Jews who settled in Portugal and Spain, and adopted a translated form of their family name to hide their Judean origin. Sephardic Jews, are a Jewish diaspora population associated with the historic Jewish communities of the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal) and their descendants. The term Sephardic comes from Sepharad, the Hebrew word for Iberia. These communities flourished for centuries in Iberia until they were expelled in the late 15th century. (Over time, Sephardic has also come to refer more broadly to Jews, particularly in the Middle East and North Africa, who adopted Sephardic religious customs and legal traditions, often due to the influence of exiles).

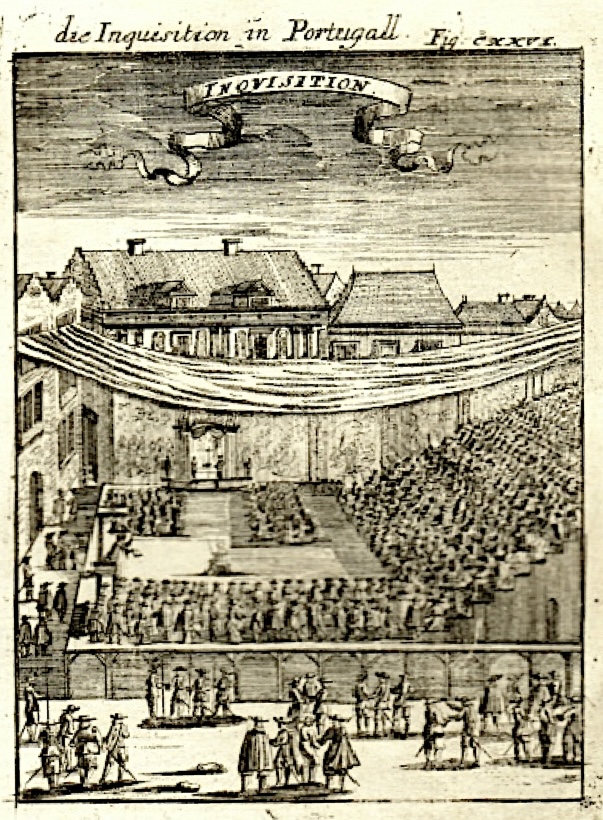

In 1492, the Alhambra Decree by the Catholic Monarchs expelled Jews from Spain, and in 1496, King Manuel I of Portugal issued a similar edict*. de Oliveira was one of the Conversos surnames adopted by Sephardic families after converting (often forced) to Christianity [Roman Catholicism]. This practice was a means of avoiding the Portuguese Inquisition [with the high probability of] prosecution and possible torture, if found as non-Catholics.

We learned from historian Laurence Bergreen in his book, Over The Edge of the World, that “Manuel’s harshest policies concerned the Jews of Portugal, who distinguished themselves as scientists, artisans, merchants, scholars, doctors, and cosmographers. In 1496, when King Manuel wished to take the daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella as his wite, he was told that he could do so only on condition that he “purify” Portugal by expelling the Jews, as Spain had done four years earlier. Rather than lose this valuable segment of the population, Manuel encouraged conversions to Christianity — forced conversions, in many cases. As ‘new Christians’ (the title fooled no one), Portuguese Jews continued to occupy high positions in the government, and received royal trading concessions, in Brazil especially.” (Bergreen, see footnotes).

*Both the Spanish and Portuguese edicts ordered their respective Jewish residents to choose one of only three options: 1) Convert to Catholicism and therefore to be allowed to remain within the kingdom, 2) Remain Jewish and be expelled by the stipulated deadline, or 3) to be summarily executed. (Wikitree)

(Image courtesy of Turning Portuguese via BBC News, and Wikipedia).

Despite Conversos Surnames, People Were Not Safe

In 1506, a Lisbon mob invaded one of the city’s old Jewish quarters and massacred around 3,000 people – including women and children. Under Manuel’s heir, João III, the Inquisition was set up in Portugal in 1536, focusing on New Christians suspected of secretly practising their old faith. It’s thought more than 40,000 individuals were charged by the Inquisition, which lasted until 1821 although the last public trial was in 1765. (BBC News)

According to historian Anita Novinsky of the University of São Paulo, a scholar of the Portuguese Inquisition, 1 out of every 3 Portuguese who arrived in Brazil in the first decades of the 16th century… were of Jewish descent. The de Oliveira(s) concentrated mainly in the Northeast Region and Minas Gerais in southeast Brazil. The chronicles of the time themselves attest to the presence of Levi, Levy, and de Oliveira families in large numbers in colonial Brazil.” (All above, except for BBC News and Wikitree, are derived from Wikipedia).

“The surname Oliveira, [is the] third most common in Brazil and sixth in Portugal.” (Oliveira Ledo Family, see footnotes). (6)

circa 1511. (See footnotes).

All Eyes On The Horizon

“The Portuguese began systematically exploring the Atlantic coast of Africa in 1418, under the sponsorship of Prince Henry the Navigator. In 1488, Bartolomeu Dias reached the Indian Ocean by this route.”

“In 1492, the Catholic Monarchs of Spain funded Genoese mariner Christopher Columbus’s plan to sail west to reach the Indies, by crossing the Atlantic. Columbus encountered a continent uncharted by Europeans (though it had been explored and temporarily colonized by the Norse 500 years earlier). Portugal quickly claimed those lands under the terms of the Treaty of Alcáçovas, but Castile was able to persuade the Pope, who was Castilian, to issue four papal bulls to divide the world into two regions of exploration, where each kingdom had exclusive rights to claim newly discovered lands. These were modified by the Treaty of Tordesillas, ratified by Pope Julius II.” Importantly, at the time, none of these explorers knew the true complete extent of the New World.

In 1498, a Portuguese expedition commanded by Vasco da Gama reached India by sailing around Africa, opening up direct trade with Asia. While other exploratory fleets were sent from Portugal to northern North America, Portuguese India Armadas also extended this Eastern oceanic route, touching South America and opening a circuit from the New World to Asia (starting in 1500 by Pedro Álvares Cabral), and explored islands in the South Atlantic and Southern Indian Oceans. The Portuguese sailed further eastward, to the valuable Spice Islands in 1512, landing in China one year later. Japan was reached by the Portuguese in 1543. East and west exploration overlapped in 1522, when a Spanish expedition sailing westward, led by Portuguese navigator Ferdinand Magellan (and, after his death in what is now the Philippines, by navigator Juan Sebastián Elcano), completed the first circumnavigation of the world.

Spanish conquistadors explored the interior of the Americas, and some of the South Pacific islands. Their main objective was to disrupt Portuguese trade in the East.”

In summary, “As one of the earliest participants in the Age of Discovery, Portugal made several seminal advancements in nautical science. The Portuguese subsequently were among the first Europeans to explore and discover new territories and sea routes, establishing a maritime empire of settlements, colonies, and trading posts that extended mostly along the South Atlantic and Indian Ocean coasts.” (Wikipedia) (7)

“The sea with an end can be Greek or Roman,

attributed to Portuguese poet and writer Fernando Pessoa

but the endless sea is Portuguese.”

Starting in 1500… the Coutinhos As New World Colonizers

Brazil is a remarkably old country when compared to a country like the United States, which is thought of as being about half the age of Brazil. In the present day, these countries have an important characteristic in common: they are both immigrant-inspired democratic republics, and each one has their own Constitution. Initially, each place was a far-flung colony of a distant European Kingdom, and the paths each took to the present day are quite different. (8)

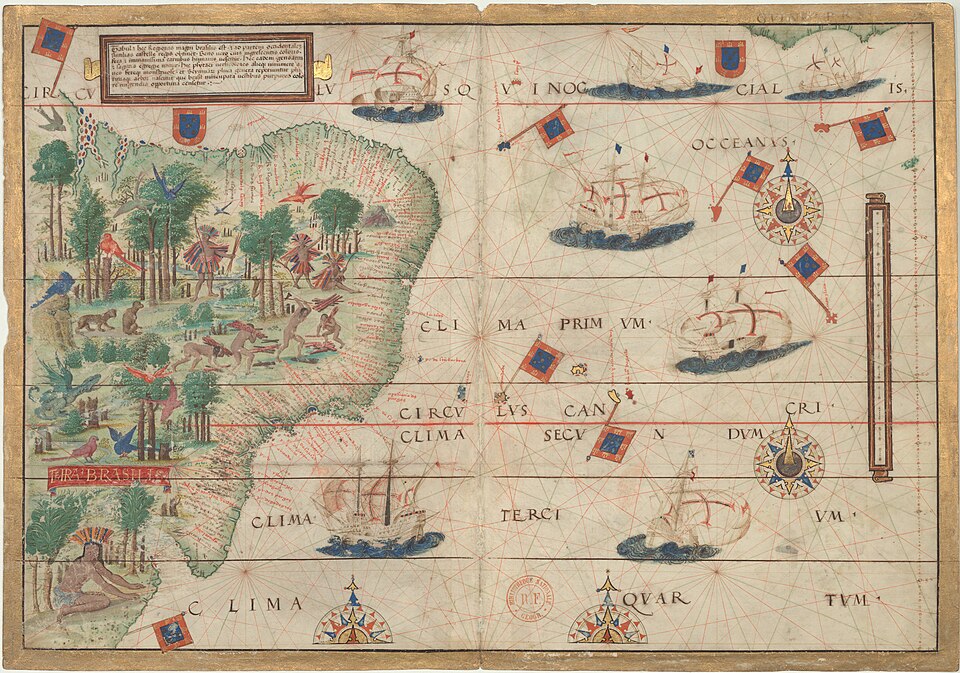

(Image courtesy of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, via Wikimedia).

Old Brazil: From Colonial Captaincies to The First Republic

The Crown in Portugal, as did other sea-faring kingdoms, viewed resource extraction as the primary reason for having a colony. Simply put, they wanted all the resources and the wealth which this brought. “Colonial Brazil, sometimes referred to as Portuguese America, comprises the period from 1500, with the arrival of the Portuguese (at what they then aptly named Porto Seguro), until 1822, when Brazil was elevated to a kingdom in union with Portugal. During the 300 years of Brazilian colonial history, the main economic activities of the territory were based first on brazilwood extraction (brazilwood cycle), which gave the territory its name; sugar production (sugar cycle); and finally on gold and diamond mining (gold cycle). Slaves, especially those brought from Africa, provided most of the workforce of the Brazilian export economy after a brief initial period of Indigenous slavery to cut brazilwood.”

“In 1630, the Dutch conquered the prosperous sugarcane-producing area in the northeast region of the Portuguese colony of Brazil. Although it only lasted for 24 years, the Dutch colony resulted in substantial art production. The governor Johan Maurits van Nassau-Siegen brought the artist, Albert Eckhout to Brazil to document the local flora, fauna, people, and customs.”

“Beginning in the early 16th century, the Portuguese monarchy used proprietorships or captaincies—land grants with extensive governing privileges—as a tool to colonize new lands… The history of the captaincies is turbulent, reflecting the needs of the Kings of Portugal, a small European country, to colonize and govern an enormous expanse of South America. Throughout the early colonial era Captaincies were granted, divided, subordinated, annexed, and abandoned. In 1548-49 when the captaincy of Baía de Todos os Santos (Bahia) reverted to the Crown due to [a] massacre, by indigenous cannibals, of its donee [a person given the gift of a powerful appointment], Francisco Pereira Coutinho [appointed on March 5, 1534] and his settlers; the King, Dom João III, established a royal governor (later a governor-general) at Bahia.”

In 1549, there were more troubles with the local native Peoples, and to make a complicated history much shorter — Captain Francisco Pereira Coutinho “was consumed by the Tupinambá in a cannibalistic feast” (!)

the Captaincy Colonies of Brazil were united into the Governorate General of Brazil,

where they were provincial captaincies of Brazil. In the list on the right side of the map, the Coutinho family is listed as entry seven for Bahia. (Map courtesy of Wikipedia).

Brazil became independent of Portugal with the signing of the Treaty of Rio de Janeiro in 1825. For three years there had been “a series of political and military events that led to the independence” based upon the date of September 7, 1822 “when prince regent Pedro of Braganza declared the country’s independence from the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves on the banks of the Ipiranga brook… in what became known as the Cry of Ipiranga.” (9)

The Coutinho Family and The Oliveira Family Immigrate to Brazil

The Northeast Region of Brazil was the first area of discovery in Brazil, when roughly 1,500 Portuguese arrived on April 22, 1500. In the mid-16th century, settlers from Spain and Portugal, Olinda, and Itamaracá founded Filipéia de Nossa Senhora das Neves (today João Pessoa) at the mouth of the Paraíba do Norte River.

The Coutinho Family

It is certain that families with the surname Coutinho immigrated to Brazil during the colonial period, as we have already written about the lurid death of Francisco Pereira Coutinho of the Bahia Captaincy (see above). “Upon the discovery of Pereira Coutinho’s death, King João immediately appropriated the captaincy from its heir Manuel Pereira Coutinho in exchange for a hereditary pension of 400,000 reals. [The family was not interested in remaining in the Americas in any case.]” (Wikipedia) With that knowledge, we are sure that the Coutinho family line begins elsewhere in Brazil. We just don’t yet know who, nor where, the original immigrant was for this family line, until more records shake loose.

The Oliveira Family As Conversos in Brazil

The history of the Jews in Brazil is a rather long and complex one, as it stretches from the very beginning of the European settlement in the new continent. Although only baptized Christians were subject to the Inquisition, Jews started settling in Brazil when the Inquisition reached Portugal, in the 16th century. They arrived in Brazil during the period of Dutch rule, setting up in Recife the first synagogue in the Americas, the Kahal Zur Israel Synagogue, as early as 1636. As a colony of Portugal, Brazil was affected by the 300 years of repression of the Portuguese Inquisition, [which quickly enough] expanded its scope of operations from Portugal to Portugal’s colonial possessions, including Brazil, Cape Verde, and Goa, where it continued investigating and trying cases based on supposed breaches of orthodox Roman Catholicism until 1821.

Most Portuguese settlers in Brazil, who throughout the entire colonial period tended to originate from Northern Portugal, moved to the northeastern part of the country to establish the first sugar plantations. In his The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith attributed much of the development of Brazil’s sugar industry and cultivation to the arrival of Portuguese Jews who were forced out of Portugal during the Inquisition.

Interestingly, and somewhat ironically, many of the Jews who had been Sephardic Jews who had fled the Inquisition in Spain and Portugal to the religious freedom of the Netherlands. From 1630 to 1654 the Dutch controlled a long stretch of Northeastern Brazilian coast. In 1648-49 the [Portuguese] Brazilians defeated the Dutch in the first and second battles of Guararapes, and gradually recovered the Portuguese colonies of Brazil.

(Derived from both Wikitree and Wikipedia) (10)

Historically, Why Were The Portuguese Attracted to Brazil?

The Portuguese people were not the only people who immigrated to Brazil, even though they are our focus for this family history. We learned some specifics we would like to discuss to help frame the long continuous stream of people immigrating from Portugal in Europe, to Brazil in South America:

- “From 1500, when the Portuguese reached Brazil, until its independence in 1822, from 500,000 to 700,000 Portuguese settled in Brazil, 600,000 of whom arrived in the 18th century alone.

- Between 1820 and 1876, 350,117 immigrants entered Brazil. Of these, 45.73% were Portuguese, [when] the total number of immigrants per year averaged 6,000].

- From 1877 to 1903, almost two million immigrants arrived, at a rate of 71,000 per year.

- From 1904 to 1930, 2,142,781 immigrants came to Brazil; the Portuguese constituted 38% of entries…” (Family Search)

Top row, left to right: Ruins of: St. Nicholas Church, São Paulo Church, Patriarchal Square.

Bottom row, left to right: Lisbon Cathedral, Tower of São Roque or Tower of the Patriarch,

Royal Opera House. Engravings by the French artist Jacques Philippe Le Bas, 1757.

(Images courtesy of get Lisbon).

After the 1755 Lisbon earthquake devastated that city, the country of Portugal was never the same again. It was (no pun intended), literally uprooted as a world class city. Over the centuries, it began experiencing severe economic problems, financial instability, and political turmoil, which drove many to seek opportunities elsewhere. Thus, Brazil became a significant destination for those fleeing poverty and seeking a better life. This sense of instability pushed many to emigrate. (Derived from Instituto de Ciências Sociasis).

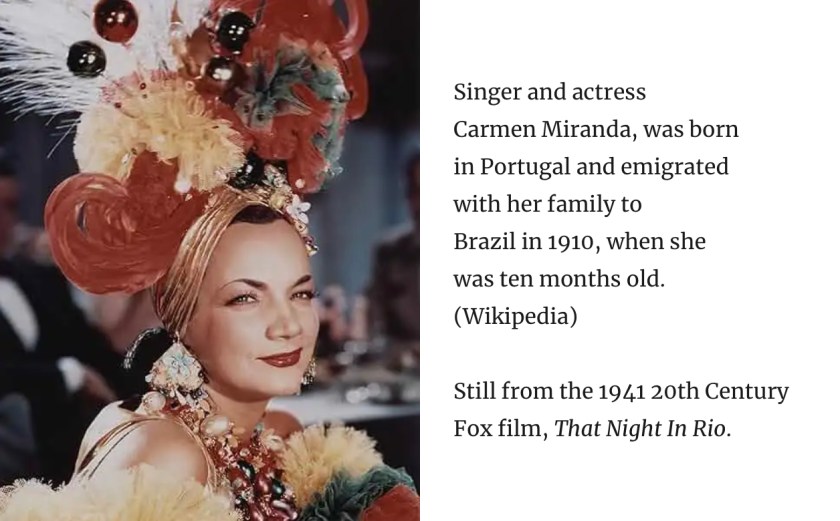

“Portuguese Brazilians are Brazilian citizens whose ancestry originates wholly or partly in Portugal. Most of the Portuguese who arrived throughout the centuries in Brazil sought economic opportunities. Although present since the onset of the colonization, Portuguese people began migrating to Brazil in larger numbers and without state support in the 18th century.

The majority settled in urban centers, mainly in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, working mainly as small traders, shopkeepers, porters, cobblers, and drivers. A smaller number became coal miners, dairy workers, and small-scale farmers outside of urban areas. Upheavals in Portugal after the 1910 Revolution and the establishment of the First Portuguese Republic caused a temporary exodus of Portuguese to Brazil.” (Wikipedia)

In the next chapter, we move forward with what we do know about the Coutinho and the De Azevedo families. Their lives unfold in the Brazilian states of Minas Gerais, Bahia, and Paraíba. Unlike many family lines we have researched in other chapters — we learn much about them through the lines of their grandmothers, rather than their grandfathers. (11)

Following are the footnotes for the Primary Source Materials,

Notes, and Observations

Intertwined

(1) — two records

> The family photograph (and wedding announcement below) in this section are from the personal family collection.

June 2008 Wedding Announcement

for Thomas Harley Bond and Leandro José Oliveira Coutinho

What Does the Coutinho Family Name Mean in Portugal?

(2) — five records

The British Historical Society of Portugal

Battle of Aljubarrota, 1385

https://www.bhsportugal.org/anglo-portuguese-timeline/battle-of-aljubarrota

Note: For the image and text.

Wisdom Library

Meaning of The Name Coutinho

https://www.wisdomlib.org/names/coutinho#google_vignette

Note: For the text.

Coutinho

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coutinho

Note: For the text.

Ferdinand I of Portugal

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ferdinand_I_of_Portugal

and

King Ferdinand I of Portugal, (detail)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ferdinand_I_of_Portugal#/media/File:Ferdinand_I_of_Portugal_-_Chronique_d’_Angleterre_(Volume_III)_(late_15th_C),_f.201v_-_BL_Royal_MS_14_E_IV_(cropped).png

Note: For his image.

The Marshals of the Kingdom of Portugal

(3) — sixteen records

Marshal of Portugal

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marshal_of_Portugal

Note: For the text.

Count of Marialva

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Count_of_Marialva

Note: For the text and the Coutinho Coat-of-Arms.

Geneall

https://geneall.net/pt/titulo/739/condes-de-marialva/

Note 1: This website references this book,

Nobreza de Portugal e Brasil

Editorial Enciclopédia, Edição: 2, Lisboa 1989

Available at this link:

https://www.livraria-ler-com-gosto.com/nobreza-de-portugal-e-do-brasil-3-vols

Note 2: For the data.

These above volumes are also available as .pdf downloads at:

Volume 1

Open Repository of the University of Porto

https://repositorio-aberto.up.pt/handle/10216/9376

File: tesedoutnobrezav01000065918.pdf

Volume 2

https://repositorio-aberto.up.pt/handle/10216/9376

File: tesedoutnobrezav02000065920.pdf

Volume 3

MOA %E2%80%94 12.pdf

Vasco Fernandes Coutinho, 1st Count of Marialva

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vasco_Fernandes_Coutinho,_1st_Count_of_Marialva

Note: For the data.

Gonçalo Coutinho, 2nd Count of Marialva

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gonçalo_Coutinho,_2nd_Count_of_Marialva

Note: For the data.

Francisco Coutinho, 4th Count of Marialva

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francisco_Coutinho,_4th_Count_of_Marialvaand

Beatriz de Meneses, 2nd Countess of Loulé

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beatriz_de_Meneses,_2nd_Countess_of_Loulé

Note: For the data.

Count of Loulé

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Count_of_Loulé

and

Infante Ferdinand, Duke of Guarda

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Infante_Ferdinand,_Duke_of_Guarda

Note: For the data.

Costa of of the Coutinho family, counts of Marialva and counts of Loulé

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Armas_condes_marialva.svg

Note: The Coutinho Coat-of-Arms source file.

The Ancient Heraldry of the Coutinho Family

(4) — five records

Portuguese Heraldry

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portuguese_heraldry

Note: For the text and artwork.

Livro Do Armeiro Mor, João Do Cró (ou João Du Cros)

by João do Cró (ou João du Cros), circa 1509

https://archive.org/details/livro-do-armeiro-mor-joao-do-cro-ou-joao-du-cros-backup/mode/2up

Note: Count of Marialva (Coutinho), folio 48

https://archive.org/details/livro-do-armeiro-mor-joao-do-cro-ou-joao-du-cros-backup/page/n111/mode/2up

Digital page: 112/292

Coats-of-arms of principal families of the Portuguese nobility

in the Thesouro de Nobreza, 1675.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portuguese_heraldry#/media/File:Fl-_27_Thesouro_de_Nobreza,_Armas_das_Familias_(cropped).jpg

Note 1: Observe the Coat-of-Arms of the Coutinho family in the lower right corner.

Note 2: For the artwork.

Portuguese Nobility

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portuguese_nobility

Note: for the text.

We Are From Two of the 72 Portuguese Noble Class Families

(5) — four records

Lifecooler

Palácio Nacional de Sintra (Palácio da Vila)

https://lifecooler.com/artigo/dormir/palcio-nacional-de-sintra-palcio-da-vila/326883

Note: For the Sala dos Brasões photograph.

(Image courtesy of the Libro das Fortalezas via Wikimedia Commons).

Sintra National Palace

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sintra_National_Palace

Note: For the text and the image above.

Livro Do Armeiro Mor, João Do Cró (ou João Du Cros)

by João do Cró (ou João du Cros), circa 1509

https://archive.org/details/livro-do-armeiro-mor-joao-do-cro-ou-joao-du-cros-backup/mode/2up

Note: Azevedo, folio 61

https://archive.org/details/livro-do-armeiro-mor-joao-do-cro-ou-joao-du-cros-backup/page/n135/mode/2up

Digital page: 136/292

What Does the Oliveira Family Name Mean in Portugal?

(6) — sixteen records

Oliveira (surname)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oliveira_(surname)

Note: For the text.

Google Image Search

Shields of the Twelve Tribes of Israel

by Pieter Mortier, 1705

https://www.posterazzi.com/shields-of-the-twelve-tribes-of-israel-from-a-work-published-by-pieter-mortier-in-amsterdam-1705-poster-print-by-ken-welsh-11-x-17/

Note: This image is sourced from the contemporary website Posterazzi, but its original source is the “Shields of the twelve tribes of Israel, from a work published by Pieter Mortier in Amsterdam, 1705”.

Livro Do Armeiro Mor, João Do Cró (ou João Du Cros)

by João do Cró (ou João du Cros), circa 1509

https://archive.org/details/livro-do-armeiro-mor-joao-do-cro-ou-joao-du-cros-backup/mode/2up

Note: Armorial artwork for Oliveira, folio 128

https://archive.org/details/livro-do-armeiro-mor-joao-do-cro-ou-joao-du-cros-backup/page/n263/mode/2up

Digital page: 264/292, Right page, in the upper left corner.

Sephardic Jews

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sephardic_Jews

Note: For the text.

Alhambra Decree

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alhambra_Decree

Note: For the reference.

Wikitree

De Oliveira Name Study

https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Space:De_Oliveira_Name_Study

Note: For the text.

Manuel I of Portugal

by Colijn de Coter, circa 1515

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manuel_I_of_Portugal

Note: For his portrait.

Isabella I of Castile

by Unknown artist, circa 1490

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isabella_I_of_Castile

Note: For her portrait.

Ferdinand II of Aragon

by Michael Sittow, circa 1450

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ferdinand_II_of_Aragon

Note: For his portrait.

Jewish Gen

The Jeff Malka Sephardic Collection: Sephardim.com Namelist

https://jewishgen.org/databases/sephardic/SephardimComNames.html

Note: For the data about the family surname de Oliveira.

Over The Edge of the World

by Laurence Bergreen

Chapter One: The Quest, paragraph 29

Note: We do not have a digital link to the text, but the book can be referenced here in English:

Over The Edge of the World

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Over_the_Edge_of_the_World

BBC News

Turning Portuguese

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/resources/idt-sh/Turning_Portuguese

Note: For the text.

Wikitree

de Oliveira of Paraíba, Brazil

https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Space:De_Oliveira%27s_of_Paribia%2C_Brazil

Note: For the text under the subhead, Sephardi Jews Settlement and Expulsion From Spain and Portugal

Representation of Executions by Fire in Terreiro do Paço, in Lisbon, Portugal.

https://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inquisição

Note: For the engraved illustration.

Martins Castro

Oliveira Ledo Family: From Brick Making to the Colonization of Paraíba

https://martinscastro.pt/en/blogs/familia-oliveira-ledo/

Note: For this text —

“The surname Oliveira, [is the] third most common in Brazil and sixth in Portugal”.

All Eyes On The Horizon

(7) — fifteen records

Age of Discovery

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Age_of_Discovery

Note: For the text.

Prince Henry the Navigator

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prince_Henry_the_Navigator

and

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prince_Henry_the_Navigator#/media/File:Henry_the_Navigator1.jpg

Note 1: Portrait attributed to painter Nuno Gonçalves, circa 1450.

Note 2: From the description, “Detail of standing man with moustache and Burgundian-style chaperon in the Panel of the Prince (third panel of the St. Vincent panels, usually dated c.1470, attributed to painter Nuno Gonçalves). This figure is most commonly identified as Prince Henry the Navigator (died 1460, aged 66). Several scholars (e.g. Markl, 1994; Salvador Marques, 1998) have recently disputed this identification, and instead proposed this to be an image of King Edward of Portugal (d. 1438, aged 47), although this is not yet widely accepted.”

Note 3: For his portrait.

Christopher Columbus

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christopher_Columbus

and

Portrait of a Man, Said to be Christopher Columbus

by Unknown painter

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christopher_Columbus#/media/File:Portrait_of_a_Man,_Said_to_be_Christopher_Columbus.jpg

Note: For his portrait.

Pope Julius II

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pope_Julius_II

and

Portrait if Pope Julius II

by Raphael

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Pope_Julius_II.jpg#/media/File:Pope_Julius_II.jpg/2

Note: For his portrait.

Planisphere World Map

by Francesco Rosselli, circa 1508

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:World_map_RMG_C4568_1.jpg

Note: For the map image.

(Image courtesy of the National Library of Portugal via Wikimedia Commons).

Vasco da Gama

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vasco_da_Gama

and

Vasco da Gama, anonymous portrait, c. 1525

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vasco_da_Gama#/media/File:Ignoto_portoghese,_ritratto_di_un_cavaliere_dell’ordine_di_cristo,_1525-50_ca._02.jpg

Note: For his portrait, and the image above.

Pedro Álvares Cabral

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pedro_Álvares_Cabral

and

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pedro_Álvares_Cabral#/media/File:Pedro_Álvares_Cabral.jpg

Note 1: From the description, “Detail of painting “Vaz de Caminha reads to Commander Cabral, Friar Henrique and Master João the letter that will be sent to King Dom Manuel I”. It depicts Pedro Álvares Cabral, leader of the Portuguese expediction that discovered the land that would later be known as Brazil in 1500.”

Note 2: For his contemporary portrait, circa 1900.

Ferdinand Magellan

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ferdinand_Magellan

and

Half-length portrait of a bearded Ferdinand Magellan

(circa 1480-1521) facing front.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ferdinand_Magellan#/media/File:Ferdinand_Magellan.jpg

Note: For his portrait.

Starting in 1500… the Coutinhos As New World Colonizers

(8) — one record

Bibliothèque Nationale de France, via Wikimedia

Map of Brazil in the Miller Atlas of 1519,

by Lopo Homem

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Brazil_16thc_map.jpg

Note: The file name is, Brazil 16thc map.jpg

Old Brazil: From Colonial Captaincies to The First Republic

(9) — nine records

Portugal

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portugal

Note: For the text.

Captaincy of Bahia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Captaincy_of_Bahia

Note: For the text.

Fernando Pessoa

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fernando_Pessoa

Note: For the reference.

Colonial Brazil

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colonial_Brazil

Note: For the text.

The National Museum of Denmark, via the Kahn Academy

Series of Eight Figures, by Albert Eckhout, 1641

by Rachel Zimmerman

https://pl.khanacademy.org/humanities/art-americas/new-spain/colonial-brazil/a/albert-eckhout-series-of-eight-figures

Note: For the artwork and text.

Captaincies of Brazil

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Captaincies_of_Brazil

Note: For the text.

Francisco Pereira Coutinho

https://ancestors.familysearch.org/pt/LYPV-1X2/francisco-pereira-coutinho-1450-1549

História do Rio para todos

Mapa de Capitanias Hereditarias

by Luiz Teixeira, circa 1574

https://historiadorioparatodos.com.br/timeline/1534-capitanias-hereditarias/km_c258-20190503153124-6/

Note: From the Collection of the Ajuda Library Foundation, Lisbon.

O Globo | Cultura

De mapas manuscritos a pintura, livro reúne imagens da Bahia entre os séculos XVII e XIX nunca antes publicadas num único volume

by Nelson Vasconcelos

https://oglobo.globo.com/cultura/noticia/2024/11/17/de-mapas-manuscritos-a-pintura-livro-reune-imagens-da-bahia-entre-os-seculos-xvii-e-xix-nunca-antes-publicadas-num-unico-volume.ghtml

Note: For the image, The Town of Cachoeira in the Province of Bahia.

The Coutinho Family and The Oliveira Family Immigrate to Brazil

(10) — seven records

Captaincy of Bahia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Captaincy_of_Bahia

Note: For the text about Manuel Pereira Coutinho.

Die Inquisition in Portugal by Jean David Zunner (1685), via Wikipedia at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portuguese_Inquisition#/media/File:1685_-_Inquisição_Portugal.jpg

Note: For the above image, Copper engraving of an auto de fé in Portugal.

History of the Jews in Brazil

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Jews_in_Brazil

Note: For the text.

Wikitree

de Oliveira of Paraíba, Brazil

https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Space:De_Oliveira%27s_of_Paribia%2C_Brazil

Note: For the text under the subhead, History of Northeastern Brazil

University of St. Andrews

Where we find new old books, chapter 4:

William Creech and a new first edition of Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations

https://university-collections.wp.st-andrews.ac.uk/2015/12/15/where-we-find-new-old-books-chapter-4-william-creech-and-a-new-first-edition-of-adam-smiths-wealth-of-nations/

Note: For the book frontispiece photograph.

Smithsonian Magazine

Sugar Masters in a New World

by Heather Pringle

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/sugar-masters-in-a-new-world-5212993/

Note: For the background top image.

Sugar Mill in Pernambuco

by Franz Post, 17th century

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Frans_Post_-_Engenho_de_Pernambuco.jpg

Note 1: File name is, Frans Post – Engenho de Pernambuco.jpg

Note 2: For the background bottom image.

Historically, Why Were The Portuguese Attracted to Brazil?

(11) — nine records

Brazilian propaganda poster incentivizing

Italian immigration to Rio de Janeiro, 1870s.

https://www.reddit.com/r/PropagandaPosters/comments/1iio0a3/brazilian_propaganda_poster_incentivizing_italian/

Note: For the poster artwork.

Estado de São Paulo Brazil O Immigrante (Europa-Santos) 1908

https://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ficheiro:Estado_de_São_Paulo_Brazil_O_Immigrante_(Europa-Santos)_1908.jpg#/media/Ficheiro:Estado_de_São_Paulo_Brazil_O_Immigrante_(Europa-Santos)_1908.jpg

Note: For the poster artwork.

Japanese Brazilian emigration propaganda poster

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Affiche_émigration_JP_au_BR-déb._XXe_s..jpg

Note: For the poster artwork.

Family Search

Portugal Emigration and Immigration

https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Portugal_Emigration_and_Immigration

Note: For the data.

Derived from:

Instituto de Ciências Sociais de Universidade de Lisboa

The “Brasileiro”: a 19th century transnational social category

Chapter 10

by Isabel Corrêa da Silva

https://www.ics.ulisboa.pt/books/book1/ch10.pdf

Note: This is .pdf file of chapter 10.

Get Lisbon

The Tragic Earthquake of 1755

https://getlisbon.com/discovering/earthquake-of-1755/

Note: For the engravings made two years after the 1755 Lisbon Earthquake by the French artist Jacques Philippe Le Bas, 1757.

IMDB

Carmen Miranda

Portrait photograph by the Donaldson Collection/Getty Images

https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0000544/mediaviewer/rm3875448065?ref_=ext_shr_eml

and

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0034273/mediaviewer/rm3703311617?ref_=ext_shr_eml

Note: For her photograph, and the movie poster.

Portuguese Brazilians

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portuguese_Brazilians

Note: For the text.